Supplementary Material for Linguistic Situation in Twenty Sub-Saharan African Countries: a Survey-Based Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Replacive Grammatical Tone in the Dogon Languages

University of California Los Angeles Replacive grammatical tone in the Dogon languages A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics by Laura Elizabeth McPherson 2014 c Copyright by Laura Elizabeth McPherson 2014 Abstract of the Dissertation Replacive grammatical tone in the Dogon languages by Laura Elizabeth McPherson Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Russell Schuh, Co-chair Professor Bruce Hayes, Co-chair This dissertation focuses on replacive grammatical tone in the Dogon languages of Mali, where a word’s lexical tone is replaced with a tonal overlay in specific morphosyntactic contexts. Unlike more typologically common systems of replacive tone, where overlays are triggered by morphemes or morphological features and are confined to a single word, Dogon overlays in the DP may span multiple words and are triggered by other words in the phrase. DP elements are divided into two categories: controllers (those elements that trigger tonal overlays) and non-controllers (those elements that impose no tonal demands on surrounding words). I show that controller status and the phonological content of the associated tonal overlay is dependent on syntactic category. Further, I show that a controller can only impose its overlay on words that it c-commands, or itself. I argue that the sensitivity to specific details of syntactic category and structure indicate that Dogon replacive tone is not synchronically a phonological system, though its origins almost certainly lie in regular phrasal phonology. Drawing on inspiration from Construction Morphology, I develop a morphological framework in which morphology is defined as the id- iosyncratic mapping of phonological, syntactic, and semantic information, explicitly learned by speakers in the form of a construction. -

5 Phonology Florian Lionnet and Larry M

5 Phonology Florian Lionnet and Larry M. Hyman 5.1. Introduction The historical relation between African and general phonology has been a mutu- ally beneficial one: the languages of the African continent provide some of the most interesting and, at times, unusual phonological phenomena, which have con- tributed to the development of phonology in quite central ways. This has been made possible by the careful descriptive work that has been done on African lan- guages, by linguists and non-linguists, and by Africanists and non-Africanists who have peeked in from time to time. Except for the click consonants of the Khoisan languages (which spill over onto some neighboring Bantu languages that have “borrowed” them), the phonological phenomena found in African languages are usually duplicated elsewhere on the globe, though not always in as concen- trated a fashion. The vast majority of African languages are tonal, and many also have vowel harmony (especially vowel height harmony and advanced tongue root [ATR] harmony). Not surprisingly, then, African languages have figured dispro- portionately in theoretical treatments of these two phenomena. On the other hand, if there is a phonological property where African languages are underrepresented, it would have to be stress systems – which rarely, if ever, achieve the complexity found in other (mostly non-tonal) languages. However, it should be noted that the languages of Africa have contributed significantly to virtually every other aspect of general phonology, and that the various developments of phonological theory have in turn often greatly contributed to a better understanding of the phonologies of African languages. Given the considerable diversity of the properties found in different parts of the continent, as well as in different genetic groups or areas, it will not be possible to provide a complete account of the phonological phenomena typically found in African languages, overviews of which are available in such works as Creissels (1994) and Clements (2000). -

Nature Redacted September 7,2017 Certified By

The Universality of Concord by Isa Kerem Bayirli BA, Middle East Technical University (2010) MA, Bogazigi University (2012) Submitted to the Department of Linguistics and Philosophy in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY September 2017 2017 Isa Kerem Bayirli. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature redacted Author......................... ...... ............................. Departmeyf)/Linguistics and Philosophy Sic ;nature redacted September 7,2017 Certified by...... David Pesetsky Ferrari P. Ward Professor of Linguistics g nThesis Supervisor redacted Accepted by.................. Signature ...................................... David Pesetsky Lead, Department of Linguistics and Philosophy MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SEP 2 6 2017 LIBRARIES ARCHiVES The Universality of Concord by Isa Kerem Bayirh Submitted to the Deparment of Linguistics and Philosophy on September 7, 2017 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics Abstract In this dissertation, we develop and defend a universal theory of concord (i.e. feature sharing between a head noun and the modifying adjectives). When adjectives in a language show concord with the noun they modify, concord morphology usually involves the full set of features of that noun (e.g. gender, number and case). However, there are also languages in which concord targets only a subset of morphosyntactic features of the head noun. We first observe that feature combinations that enter into concord in such languages are not random. -

Prayer Cards | Joshua Project

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Anii in Benin Dendi, Dandawa in Benin Population: 47,000 Population: 274,000 World Popl: 66,000 World Popl: 414,700 Total Countries: 2 Total Countries: 3 People Cluster: Guinean People Cluster: Songhai Main Language: Anii Main Language: Dendi Main Religion: Islam Main Religion: Islam Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: 1.00% Evangelicals: 0.03% Chr Adherents: 2.00% Chr Adherents: 0.07% Scripture: Unspecified Scripture: New Testament www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Kerry Olson Source: Jacques Taberlet "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Foodo in Benin Fulani, Gorgal in Benin Population: 45,000 Population: 43,000 World Popl: 46,100 World Popl: 43,000 Total Countries: 2 Total Countries: 1 People Cluster: Guinean People Cluster: Fulani / Fulbe Main Language: Foodo Main Language: Fulfulde, Western Niger Main Religion: Islam Main Religion: Islam Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: 0.01% Evangelicals: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.02% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Scripture: Portions Scripture: New Testament www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Bethany World Prayer Center Source: Bethany World Prayer Center "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Fulfulde, Borgu in Benin Gbe, Seto in Benin Population: 650,000 Population: 40,000 World Popl: 767,700 World -

Investigating the Relatedness of the Endangered Dogon Languages

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2013 Investigating the Relatedness of the Endangered Dogon Languages Moran, Steven ; Prokić, Jelena Abstract: In this article we apply up-to-date methods of quantitative language comparison, inspired by algorithms successfully applied in bioinformatics to decode DNA and determine the genetic relatedness of humans, to language data in an attempt to shed light on the current situation of a family of languages called Dogon, which are spoken in Mali, West Africa. Our aim is to determine the linguistic subgroupings of these languages, which we believe will shed light on their prehistory, highlight the linguistic diversity of these groups and which may ultimately inform studies on the cultural boundaries of these languages. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqt061 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-84673 Journal Article Originally published at: Moran, Steven; Prokić, Jelena (2013). Investigating the Relatedness of the Endangered Dogon Languages. Literary and Linguistic Computing, 28(4):676-691. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqt061 Literary and Linguistic Computing Advance Access published September 17, 2013 Investigating the relatedness of the ............................................................................................................................................................endangered Dogon languages Steven Moran University -

Languages Avec Territoire Propre Au Mali 17 Mai 2006 Par Lee Hochstetler (SIL) Police Utilise'e: RCI Std Doulos = Rcidolr.Ttf

Languages avec Territoire Propre au Mali 17 mai 2006 par Lee Hochstetler (SIL) Police utilise'e: RCI Std Doulos = rcidolr.ttf BF= Burkina Faso, RCI = Ivory Coast, GH=Ghana, Gui =Guinea, GuB = Guinea Bisau, SL = Sierra Leone, Sen= Senegal, M=Mauritania, Alg =Algeria, Nig =Niger Glossonym <langue> Code Ethnologue Autre pays Nom alternatif et par qui dialectes majeurs Commentaires Hasanya Arabic [MEY] M, Sen. Appelle' hasanya arabic par SIL Mali. Appelle hasanya par gouvt malien. Appelle maure-orthographe franchise du gouvt malien. Appelld suraka par bambaraphones. Appelle suraxe par les soninke. Bamako Sign Lg. [BOG] Mali seul C.E.C.I., B.P. 109, Bamako Not related to other sign languages. Another community of deaf people in Bamako use a West African variety of American Sign Language. Bamanan<kan> [BAM] RCI, BF Appelle bamanankan par gouvt malien. Appelle bambara-orthographe franchise par gouvt malien et par bcp d'europeens. Dialectes:Bamako, Somono, Segou, San, Beledugu, Ganadugu, Wasulu, Sikasso. Banka<gooma> [BXW] Mali seul Appelle samogho par des gen£ralistes diachroniques. Parle a l'ouest de Danderesso (au nord de Sikasso). Kona<bere> [BBO] BF Appelle northern bobo madare par SIL BF. Appelle' black bobo [perj] par certains anglophones. Appelle' bobo-fin [perj] par certains bambaraphones. Appelle bobo par ceux qui generalize trop (il y a 2 varietes au BF). Ne le confondez pas avec le bomu. Bomu ou Bore [BMQ] BF Appelle bobo par gouvt malien. Boomu—un ancien orthographe du gouvt malien. Appelle' bobo oule [pej] par certains bambaraphones. Langues Maliennes.rtf Page 05/18/06 2 Appelle' red bobo [pej] par certains anglephones. -

First Steps Towards the Detection of Contact Layers in Bangime: a Multi-Disciplinary, Computer-Assisted Approach

First steps towards the detection of contact layers in Bangime: A multi-disciplinary, computer-assisted approach 1 Introduction Bangime, a language isolate spoken in central-eastern Mali, represents an enigma, not only in terms of linguistics, but also with regards to their past ethnographic affiliations and migration patterns. The speakers of Bangime, the Bangande, live among and claim to constitute one of the Dogon groups that also occupy the rocky terrain of the Bandiagara Escarpment. However, there is little evidence in support of the Bangande being genetically affiliated with the Dogon or speaking one of the estimated 21 Dogon languages, nor of their being related to the neighboring Mande-speaking groups who inhabit a valley which stretches from the west and ends at the eastern edge of the Escarpment. Further to the north of the area where Bangime is spoken lies the vast Sahara desert, the southern borders of which are occupied by Songhai-speaking populations. Throughout the region are found Fula semi-nomadic herders who speak Fulfulde. Thus, we know that the Bangande have had the opportunity to engage in contact with each of these populations, but because there are no written historical records of their past settlement and migration patterns, nor have there been any archeological investigations of the western portions of the Bandiagara Escarpment where the Bangande are found today, we must rely on data from the present to reconstruct a picture of the past. Figure 1 illustrates the geographic positions of the languages represented in the sample with respect to where Bangime is spoken. Note that the points represent approximations; languages such as Fulfulde have a reach throughout the entire region and even beyond to bordering nations. -

Works of Russell G. Schuh

UCLA Works of Russell G. Schuh Title Schuhschrift: Papers in Honor of Russell Schuh Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7c42d7th ISBN 978-1-7338701-1-5 Publication Date 2019-09-05 Supplemental Material https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7c42d7th#supplemental Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Schuhschrift Margit Bowler, Philip T. Duncan, Travis Major, & Harold Torrence Schuhschrift Papers in Honor of Russell Schuh eScholarship Publishing, University of California Margit Bowler, Philip T. Duncan, Travis Major, & Harold Torrence (eds.). 2019. Schuhschrift: Papers in Honor of Russell Schuh. eScholarship Publishing. Copyright ©2019 the authors This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Interna- tional License. To view a copy of this license, visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. ISBN: 978-1-7338701-1-5 (Digital) 978-1-7338701-0-8 (Paperback) Cover design: Allegra Baxter Typesetting: Andrew McKenzie, Zhongshi Xu, Meng Yang, Z. L. Zhou, & the editors Fonts: Gill Sans, Cardo Typesetting software: LATEX Published in the United States by eScholarship Publishing, University of California Contents Preface ix Harold Torrence 1 Reason questions in Ewe 1 Leston Chandler Buell 1.1 Introduction . 1 1.2 A morphological asymmetry . 2 1.3 Direct insertion of núkàtà in the left periphery . 6 1.3.1 Negation . 8 1.3.2 VP nominalization fronting . 10 1.4 Higher than focus . 12 1.5 Conclusion . 13 2 A case for “slow linguistics” 15 Bernard Caron 2.1 Introduction . -

Baŋgi Me, a Language of Unknown Affiliation in Northern Mali

Baŋgi me, a language of unknown affiliation in Northern Mali [DRAFT FOR COMMENT -NOT FOR CITATION WITHOUT REFERENCE TO THE AUTHOR] Roger Blench Mallam Dendo 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/Answerphone/Fax. 0044-(0)1223-560687 E-mail [email protected] http://homepage.ntlworld.com/roger_blench/RBOP.htm This printout: Cambridge, March 28, 2005 R.M. Blench Baŋgi me Wordlist Circulated for comment TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction................................................................................................................................................. 1 2. Information about the language................................................................................................................. 1 2.1 Nomenclature......................................................................................................................................... 1 2.2 Location and settlements ...................................................................................................................... 1 2.3 Language status..................................................................................................................................... 2 2.4 Baŋga na culture and history ............................................................................................................... 2 2.5 The classification of Baŋgi me.............................................................................................................. 2 3. Phonology.................................................................................................................................................... -

1 Syntax Jochen Zeller (University of Kwazulu-Natal) Draft (Version April

Zeller, Jochen. 2020. Syntax. In: Rainer Vossen and Gerrit J. Dimmendal (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of African Languages. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 66-87. Syntax Jochen Zeller (University of KwaZulu-Natal) Draft (Version April 2016) 1 Introduction In this chapter I present an overview of the basic, and what I consider the most intriguing, syntactic properties of the languages spoken on the African continent. I discuss the major syntactic word categories and general aspects of word order typology, but I also address specific topics that have attracted considerable attention in the fields of African linguistics and theoretical syntax, including topic and focus constructions, wh-questions, serial verbs and the passive. In this review, I highlight those syntactic phenomena that are mainly or exclusively found in African languages, such as e.g. logophoricity, or the so-called “verb medial” (S−Aux−O−V−X) constituent order. Occasionally, I also mention prominent generative analyses of the constructions I review.1 5.2 The sentence: basic constituent order The “basic” order of constituents in a language is typically defined by the position of subject (S), verb (V), and object (O) in declarative, affirmative, active main clauses which are morphologically and pragmatically unmarked.2 According to Heine (1976, 2008), the proportion of languages with S−V−O constituent order is much higher in Africa than globally; it is the basic order of approximately 71% of African languages (Heine 2008:5). S−V−O languages are common in all four phyla. The majority of the Niger-Congo languages is S−V−O; in fact, this constituent order is almost without exception in the Atlantic and Bantu branches (Heine 1976; Watters 2000). -

Areal Patterns in the Vowel Systems of the Macro-Sudan Belt

DRAFT 2018.09.09 Title: Areal patterns in the vowel systems of the Macro-Sudan Belt Abstract: This paper investigates the areal distribution of vowel systems in the Macro-Sudan Belt, an area of Western and Central Africa proposed in recent areal work (Güldemann 2008, Clements & Rialland 2008). We report on a survey of 681 language varieties with entries coded for two phonological features: advanced tongue root (ATR) harmony and the presence of interior vowels (i.e. non-peripheral vowels [ɨ ɯ ɜ ə ʌ …]). Our results show that the presence of ATR harmony in the Macro-Sudan Belt is limited to three geographically unconnected zones: an Atlantic ATR zone, a West African ATR zone, and an East African ATR zone. Between the West and East African ATR Zones is a genetically heterogeneous region where ATR harmony is systematically absent which we term the Central African ATR-deficient zone. Our results show that in this same Central African zone, phonemic and allophonic interior vowels are disproportionately prevalent. Based on this distribution, we highlight two issues. First, ATR and interiority have an antagonistic relationship and do not commonly co-occur within vowel systems, supported through statistical tests. Second, our survey supports the existence of the Macro-Sudan Belt, but due to ATR being systematically absent in Central Africa, this weakens the proposal that this area represents the ‘hotbed’ of the Macro-Sudan Belt (Güldemann 2008:167). Keywords: phonology, vowel systems, vowel harmony, ATR, macro-areas, areal typology, Africa 1 Introduction There has been a recent resurgence in Africanist linguistics towards areal explanations of shared linguistic features, rather than genetic explanations assuming common descent from a mother language (i.e. -

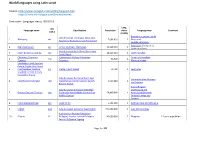

World Languages Using Latin Script

World languages using Latin script Source: http://www.omniglot.com/writing/langalph.htm https://www.ethnologue.com/browse/names Sort order : Language status, ISO 639-3 Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Botswana, Lesotho, South Indo-European, Germanic, West, Low 1. Afrikaans, afr 7,096,810 1 Africa and Saxon-Low Franconian, Low Franconian SwazilandNamibia Azerbaijan,Georgia,Iraq 2. Azeri,Azerbaijani azj Turkic, Southern, Azerbaijani 24,226,940 1 Jordan and Syria Indo-European Balto-Slavic Slavic West 3. Czech Bohemian Cestina ces 10,619,340 1 Czech Republic Czech-Slovak Chamorro,Chamorru Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian Guam and Northern 4. cha 94,700 1 Tjamoro Chamorro Mariana Islands Seychelles Creole,Seselwa Creole, Creole, Ilois, Kreol, 5. Kreol Seselwa, Seselwa, crs Creole, French based 72,700 1 Seychelles Seychelles Creole French, Seychellois Creole Indo-European Germanic North East Denmark Finland Norway 6. DanishDansk Rigsdansk dan Scandinavian Danish-Swedish Danish- 5,520,860 1 and Sweden Riksmal Danish AustriaBelgium Indo-European Germanic West High Luxembourg and 7. German Deutsch Tedesco deu German German Middle German East 69,800,000 1 NetherlandsDenmark Middle German Finland Norway and Sweden 8. Estonianestieesti keel ekk Uralic Finnic 1,132,500 1 Estonia Latvia and Lithuania 9. English eng Indo-European Germanic West English 341,000,000 1 over 140 countries Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian 10. Filipino fil Philippine Greater Central Philippine 45,000,000 1 Filippines L2 users population Central Philippine Tagalog Page 1 of 48 World languages using Latin script Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Denmark Finland Norway 11.