Title Rethinking the Orientational Prefixes in Rgyalrongic Languages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE TONES of NUMERALS and NUMERAL-PLUS-CLASSIFIER PHRASES: on STRUCTURAL SIMILARITIES BETWEEN NAXI, NA and LAZE* Alexis Michaud LACITO-CNRS

Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area Volume 34.1 — April 2011 THE TONES OF NUMERALS AND NUMERAL-PLUS-CLASSIFIER PHRASES: ON STRUCTURAL SIMILARITIES BETWEEN NAXI, NA AND LAZE* Alexis Michaud LACITO-CNRS Abstract: Numeral-plus-classifier phrases have relatively complex tone patterns in Naxi, Na (a.k.a. Mosuo) and Laze (a.k.a. Shuitian). These tone patterns have structural similarities across the three languages. Among the numerals from ‘1’ to ‘10’, three pairs emerge: ‘1’ and ‘2’ always have the same tonal behaviour; likewise, ‘4’ and ‘5’ share the same tone patterns, as do ‘6’ and ‘8’. Even those tone patterns that are irregular in view of the synchronic phonology of the languages at issue are no exception to the structural identity within these three pairs of numerals. These pairs also behave identically in numerals from ‘11’ to ‘99’ and above, e.g. ‘16’ and ‘18’ share the same tone pattern. In view of the paucity of irregular morphology—and indeed of morphological alternations in general—in these languages, these structural properties appear interesting for phylogenetic research. The identical behaviour of these pairs of numerals originates in morpho- phonological properties that they shared at least as early as the stage preceding the separation of Naxi, Na and Laze, referred to as the Proto-Naish stage. Although no reconstruction can be proposed as yet for these shared properties, it is argued that they provide a hint concerning the phylogenetic closeness of the three languages. Keywords: tone; numerals; classifiers; morpho-tonology; Naxi; Na; Mosuo; Laze; Muli Shuitian; Naish languages; phylogeny. 1. -

An Internal Reconstruction of Tibetan Stem Alternations1

Transactions of the Philological Society Volume 110:2 (2012) 212–224 AN INTERNAL RECONSTRUCTION OF TIBETAN STEM ALTERNATIONS1 By GUILLAUME JACQUES CNRS (CRLAO), EHESS ABSTRACT Tibetan verbal morphology differs considerably from that of other Sino-Tibetan languages. Most of the vocalic and consonantal alternations observed in the verbal paradigms remain unexplained after more than a hundred years of investigation: the study of historical Tibetan morphology would seem to have reached an aporia. This paper proposes a new model, explaining the origin of the alternations in the Tibetan verb as the remnant of a former system of directional prefixes, typologically similar to the ones still attested in the Rgyalrongic languages. 1. INTRODUCTION Tibetan verbal morphology is known for its extremely irregular conjugations. Li (1933) and Coblin (1976) have successfully explained some of the vocalic and consonantal alternations in the verbal system as the result of a series of sound changes. Little substantial progress has been made since Coblin’s article, except for Hahn (1999) and Hill (2005) who have discovered two additional conjugation patterns, the l- and r- stems respectively. Unlike many Sino-Tibetan languages (see for instance DeLancey 2010), Tibetan does not have verbal agreement, and its morphology seems mostly unrelated to that of other languages. Only three morphological features of the Tibetan verbal system have been compared with other languages. First, Shafer (1951: 1022) has proposed that the a ⁄ o alternation in the imperative was related to the –o suffix in Tamangic languages. This hypothesis is well accepted, though Zeisler (2002) has shown that the so-called imperative (skul-tshig) was not an imperative at all but a potential in Old Tibetan. -

"Brightening" and the Place of Xixia (Tangut)

1 "Briiighttteniiing" and ttthe plllace of Xiiixiiia (Tanguttt) iiin ttthe Qiiiangiiic branch of Tiiibettto-Burman* James A. Matisoff University of California, Berkeley 1.0 Introduction Xixia (Tangut) is an extinct Tibeto-Burman language, once spoken in the Qinghai/Gansu/Tibetan border region in far western China. Its complex logographic script, invented around A.D. 1036, was the vehicle for a considerable body of literature until it gradually fell out of use after the Mongol conquest in 1223 and the destruction of the Xixia kingdom.1 A very large percentage of the 6000+ characters have been semantically deciphered and phonologically reconstructed, thanks to a Xixia/Chinese glossary, Tibetan transcriptions, and monolingual Xixia dictionaries and rhyme-books. The f«anqi\e method of indicating the pronunciation of Xixia characters was used both via other Xixia characters (in the monolingual dictionaries) and via Chinese characters (in the bilingual glossary Pearl in the Palm, where Chinese characters are also glossed by one or more Xixia ones). Various reconstruction systems have been proposed by scholars, including M.V. Sofronov/K.B. Keping, T. Nishida, Li Fanwen, and Gong Hwang-cherng. This paper relies entirely on the reconstructions of Gong.2 After some initial speculations that Xixia might have belonged to the Loloish group of Tibeto-Burman languages, scholarly opinion has now coalesced behind the geographically plausible opinion that it was a member of the "Qiangic" subgroup of TB. The dozen or so Qiangic languages, spoken in Sichuan Province and adjacent parts of Yunnan, were once among the most obscure in the TB family, loosely lumped together as the languages of the Western Barbarians (Xifan = Hsifan). -

Sino-Tibetan Languages 393

Sino-Tibetan Languages 393 Gair J W (1998). Studies in South Asian linguistics: Sinhala Government Press. [Reprinted Sri Lanka Sahitya and other South Asian languages. Oxford: Oxford Uni- Mandalaya, Colombo: 1962.] versity Press. Karunatillake W S (1992). An introduction to spoken Sin- Gair J W & Karunatillake W S (1974). Literary Sinhala. hala. Colombo: Gunasena. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University South Asia Program. Karunatillake W S (2001). Historical phonology of Sinha- Gair J W & Karunatillake W S (1976). Literary Sinhala lese: from old Indo-Aryan to the 14th century AD. inflected forms: a synopsis with a transliteration guide to Colombo: S. Godage and Brothers. Sinhala script. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University South Asia Macdougall B G (1979). Sinhala: basic course. Program. Washington D.C.: Foreign Service Institute, Department Gair J W & Paolillo J C (1997). Sinhala (Languages of the of State. world/materials 34). Mu¨ nchen: Lincom. Matzel K & Jayawardena-Moser P (2001). Singhalesisch: Gair J W, Karunatillake W S & Paolillo J C (1987). Read- Eine Einfu¨ hrung. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ings in colloquial Sinhala. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Reynolds C H B (ed.) (1970). An anthology of Sinhalese South Asia Program. literature up to 1815. London: George Allen and Unwin Geiger W (1938). A grammar of the Sinhalese language. (English translations). Colombo: Royal Asiatic Society. Reynolds C H B (ed.) (1987). An anthology of Sinhalese Godakumbura C E (1955). Sinhalese literature. Colombo: literature of the twentieth century. Woodchurch, Kent: Colombo Apothecaries Ltd. Paul Norbury/Unesco (English translations). Gunasekara A M (1891). A grammar of the Sinhalese Reynolds C H B (1995). Sinhalese: an introductory course language. -

Sino-Tibetan Numeral Systems: Prefixes, Protoforms and Problems

Sino-Tibetan numeral systems: prefixes, protoforms and problems Matisoff, J.A. Sino-Tibetan Numeral Systems: Prefixes, Protoforms and Problems. B-114, xii + 147 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1997. DOI:10.15144/PL-B114.cover ©1997 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS FOUNDING EDITOR: Stephen A. Wunn EDITORIAL BOARD: Malcolm D. Ross and Darrell T. Tryon (Managing Editors), Thomas E. Dutton, Nikolaus P. Himmelmann, Andrew K. Pawley Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in linguistic descriptions, dictionaries, atlases and other material on languages of the Pacific, the Philippines, Indonesia and southeast Asia. The authors and editors of Pacific Linguistics publications are drawn from a wide range of institutions around the world. Pacific Linguistics is associated with the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at the Australian National University. Pacific Linguistics was established in 1963 through an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund. It is a non-profit-making body financed largely from the sales of its books to libraries and individuals throughout the world, with some assistance from the School. The Editorial Board of Pacific Linguistics is made up of the academic staff of the School's Department of Linguistics. The Board also appoints a body of editorial advisors drawn from the international community of linguists. Publications in Series A, B and C and textbooks in Series D are refereed by scholars with re levant expertise who are normally not members of the editorial board. -

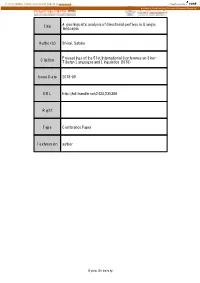

Title a Geolinguistic Analysis of Directional Prefixes In

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository A geolinguistic analysis of directional prefixes in Qiangic Title languages Author(s) Shirai, Satoko Proceedings of the 51st International Conference on Sino- Citation Tibetan Languages and Linguistics (2018) Issue Date 2018-09 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/235306 Right Type Conference Paper Textversion author Kyoto University A geolinguistic analysis of directional prefixes in Qiangic languages Satoko Shirai Japan Society for the Promotion of Science/University of Tsukuba 1 Introduction The Qiangic branch of languages are still under discussion with respect to their genealogical details such as its subclassification and position in Tibeto-Burman/Sino-Tibetan languages (Sun 1982, 1983, 2001, 2016; Thurgood 1985; Nishida 1987; Matisoff 2003; Jacques and Michaud 2011; Chirkova 2012). Although it is difficult to find shared phonological innovation in these languages, 1 they share plenty of typological characteristics such as a set of verbal prefixes to indicate the direction of movement (“directional prefixes”). Moreover, certain such typological characteristics including directional prefixes are also found in neighboring languages such as Pema, a Bodic language. This study examines the geographical distribution and relative chronology of representative directional prefixes in Qiangic languages: (i) “upward” (‘UPW’); (ii) “downward” (‘DWN’); (iii) “inward” (‘INW’), “upriver” (‘URV’), “eastward” (‘ES’), and so on; and (iv) “outward” (‘OUT’), “downriver” (‘DRV’), “westward” (‘WS’), and so on.2 Note that I not only examine single morphemes such as in (i) and (ii) but also examine a group of directional prefixes shown in (iii) and (iv), because of their semantic shifts. -

Origins of Vowel Pharyngealization in Hongyan Qiang*

Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area Volume 29.2 — October 2006 ORIGINS OF VOWEL PHARYNGEALIZATION IN HONGYAN QIANG* Jonathan Evans Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica Hongyan, a variety of Northern Qiang (Tibeto-Burman, China) has four plain vowel monophthongs /i, u, ə, a/. Vowels may be lengthened, rhotacized, or pharyngealized, resulting in fourteen short and ten long vowel phonemes. No other varieties of Qiang have been described with pharyngealization, although the other suprasegmental effects are common throughout Northern Qiang. This paper explores how the distinctions which in Hongyan are made by differences in pharyngealization are phonologized in other varieties of Northern and Southern Qiang. Comparisons are drawn with processes in other Qiangic languages and with Proto-Tibeto- Burman reconstructions, in order to explore possible routes of development of pharyngealization; the most plausible source of pharyngealization seen thus far is retraction of vowels following PTB *-w-. Keywords: Qiang, pharyngealization, brightening, Tibeto-Burman. * Special thanks to the suggestions and help of David Bradley, Zev Handel, Randy LaPolla, James Matisoff, John Ohala, and Jackson Sun. They do not necessarily agree with all of the conclusions drawn herein. Thanks to Chenglong Huang, linguist and native Qiang speaker, for providing Ronghong Yadu data, analysis, and discussion. This research was supported by my home institution, and by a grant from the National Science Council of Taiwan (94-2411-H-001-071). 95 96 Jonathan Evans 1. INTRODUCTION TO HONGYAN Qiang (羌) is a Tibeto-Burman language spoken in the Aba Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture (啊壩藏族羌藏族自治州) of Sichuan Province, China. It has been divided into two major dialects, Northern (NQ) and Southern (SQ) by H. -

Reconsidering the Diachrony of Tone in Rma1

Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society JSEALS Vol. 13.1 (2020): 53-85 ISSN: 1836-6821, DOI: http://hdl.handle.net/10524/52460 University of Hawaiʼi Press RECONSIDERING THE DIACHRONY OF TONE IN RMA1 Nathaniel A. Sims University of California Santa Barbara [email protected] Abstract Prior work has suggested that proto-Rma was a non-tonal language and that tonal varieties underwent tonogenesis (Liú 1998, Evans 2001a-b). This paper re-examines the different arguments for the tonogenesis hypothesis and puts forward subgroup-internal and subgroup- external evidence for an alternative scenario in which tone, or its phonetic precursors, was present at the stage of proto-Rma. The subgroup-internal evidence comes from regular correspondences between tonal varieties. These data allow us to put forward a working hypothesis that proto-Rma had a two-way tonal contrast. Furthermore, existing accounts of how tonogenesis occurred in the tonal varieties are shown to be problematic. The subgroup-external evidence comes from regular tonal correspondences to two closely related tonal Trans- Himalayan subgroups: Prinmi, a modern language, and Tangut, a mediaeval language attested by written records from the 11th to 16th centuries. Regular correspondences among the tonal categories of these three subgroups, combined with the Rma-internal evidence, allow us to more confidently reconstruct tone for proto-Rma. Keywords: Tonogenesis, Trans-Himalayan (Sino-Tibetan), Rma, Prinmi, Tangut, Historical linguistics ISO 639-3 codes: qxs, pmi, pmj, txg 1. Introduction This paper addresses the diachrony of tone in Rma,2 a group of northeastern Trans-Himalayan3 language varieties spoken in 四川 Sìchuān, China. -

Contact-Induced Tonogenesis in Southern Qiang*

LANGUAGE AND LINGUISTICS 2.2:63-110, 2001 Contact-Induced Tonogenesis in Southern Qiang* Jonathan P. Evans Michigan State University and Oakland University In the Qiang language, the Southern dialects (SQ) exploit tones to make lexical distinctions, while the Northern dialects (NQ) lack tonal phenomena. There are also a few transitional dialects in which tones distinguish a few minimal pairs; each pair includes at least one borrowing from Chinese. Attempts have been made (e.g., Liu 1998a) to correlate the tones of SQ with certain phonetic features of NQ dialects (e.g., consonant cluster initials and vowel quantity/quality/rhotacization). This paper presents evidence that SQ was a pitch accent language which has undergone contact-induced tonogenesis; viz., after undergoing phonological simplifications that made SQ dialects tone-prone, lexical borrowings from a tonal language (Sichuanese Mandarin) caused the beginnings of tonal distinctions. Some dialects (Longxi, Taoping) have developed full-blown tonal systems, while others (Mianchi, Heihu) have layers of tonal strata over pitch accent systems. There appear to be phonetic motivations for some accented syllables and for certain minor tones, which are of relatively recent origin. Key words: Qiang, tonogenesis, lexical stress, pitch accent, language contact 1. Introduction This paper consists of six sections. In the following section I introduce the tonal systems of the key SQ dialects. In section 3 the argument is made that tone in Southern Qiang is an innovation, and not a retention which was lost in Northern Qiang. In the fourth section I propose a course of development for the genesis of tones in Southern Qiang, and in the fifth section I set forth evidence that the development of the SQ *pitch-accent system was influenced by tonogenetic factors. -

The Qiangic Subgroup from an Areal Perspective: a Case Study of Languages of Muli

LANGUAGE AND LINGUISTICS 13.1:133-170, 2012 2012-0-013-001-000299-1 The Qiangic Subgroup from an Areal Perspective: A Case Study of Languages of Muli Katia Chirkova CRLAO, CNRS In this paper, I study the empirical validity of the hypothesis of “Qiangic” as a subgroup of Sino-Tibetan, that is, the hypothesis of a common origin of thirteen little-studied languages of South-West China. This study is based on ongoing work on four Qiangic languages spoken in one locality (Muli Tibetan Autonomous County, Sichuan), and seen in the context of languages of the neighboring genetic subgroups (Yi, Na, Tibetan, Sinitic). Preliminary results of documentation work cast doubt on the validity of Qiangic as a genetic unit, and suggest instead that features presently seen as probative of the membership in this subgroup are rather the result of diffusion across genetic boundaries. I furthermore argue that the four local languages currently labeled Qiangic are highly distinct and not likely to be closely genetically related. Subsequently, I discuss Qiangic as an areal grouping in terms of its defining characteristics, as well as possible hypotheses pertaining to the genetic affiliation of its member languages currently labeled Qiangic. I conclude with some reflections on the issue of subgrouping in the Qiangic context and in Sino-Tibetan at large. Key words: Qiangic, classification, areal linguistics, Sino-Tibetan 1. Introduction This paper examines the empirical validity of the Qiangic subgrouping hypothesis, as studied in the framework of the project “What defines Qiang-ness: Towards a This is a reworked version of a paper presented at the International Symposium on Sino- Tibetan Comparative Studies in the 21st Century, held at the Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan on June 24-25, 2010. -

On the Position of Baima Within Tibetan: a Look from Basic Vocabulary Ekaterina Chirkova

On the Position of Baima within Tibetan: A Look from Basic Vocabulary Ekaterina Chirkova To cite this version: Ekaterina Chirkova. On the Position of Baima within Tibetan: A Look from Basic Vocabulary. Alexander Lubotsky, Jos Schaeken and Jeroen Wiedenhof. Rodopi, pp.23, 2008, Evidence and counter- evidence: Festschrift F. Kortlandt. halshs-00104311 HAL Id: halshs-00104311 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00104311 Submitted on 6 Oct 2006 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Katia Chirkova August 2005 On the position of Báimǎ within Tibetan: A look from basic vocabulary1 1. Introduction Báimǎ 白马 is a Tibeto-Burman language, spoken by approximately 10,000 residents of three counties in Sìchuān 四川 Province: Jiǔzhàigōu 九寨沟; Sōngpān 松潘 (Zung-chu) and Píngwǔ 平武; and in Wénxiàn 文县 in Gānsù 甘肃 Province. The Báimǎ people call themselves [pe] and are referred to as Dwags-po in Tibetan. They reside in the immediate neighbourhood of Qiāng 羌 (to their South-West), Chinese (East and South) and Tibetan ethnic groups (West and North). The status of the Báimǎ language—separate language or Tibetan dialect—is a matter of controversy. -

Phonetics and Phonology of Nyagrong Minyag: an Endangered Language of Western China

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA PHD DISSERTATION The Phonetics and Phonology of Nyagrong Minyag, an Endangered Language of Western China John R. Van Way 2018 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE UHM GRADUATE DIVISION IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN LINGUISTICS DISSERTATION COMMITTEE: Lyle Campbell, Chairperson Victoria Anderson Bradley McDonnell Jonathan Evans Daisuke Takagi Dedicated to the people of Nyagrong khatChO Acknowledgments Funding for research and projects that have led to this dissertation has been awarded by the Endan- gered Languages Documentation Program, the Bilinski Foundation, the Firebird Foundation, and the National Science Foundation East Asia and Pacific Summer Institute. This work would not have been possible without the generous support of these funding agencies. My deepest appreciation goes to Bkrashis Bzangpo, who shared his language with me and em- barked on this journey of language documentation with me. Without his patience, kindness and generosity, this project would not have been possible. I thank the members of Bkrashis’s family who lent their time and support to his project. And I thank the many speakers of Nyagrong Minyag who gave their voices to this project. I would like to thank the many teachers who have inspired, encouraged and supported the re- search and writing of this dissertation. First, I would like to acknowledge my mentor and advisor, Lyle Campbell, who taught me so much about linguistics, fieldwork and language documentation. His support has helped me in myriad ways throughout the journey of graduate school—coursework, funding applications, research, fieldwork, writing, etc. Lyle has inspired me to be the best mentorI can to my own students.