An Internal Reconstruction of Tibetan Stem Alternations1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE TONES of NUMERALS and NUMERAL-PLUS-CLASSIFIER PHRASES: on STRUCTURAL SIMILARITIES BETWEEN NAXI, NA and LAZE* Alexis Michaud LACITO-CNRS

Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area Volume 34.1 — April 2011 THE TONES OF NUMERALS AND NUMERAL-PLUS-CLASSIFIER PHRASES: ON STRUCTURAL SIMILARITIES BETWEEN NAXI, NA AND LAZE* Alexis Michaud LACITO-CNRS Abstract: Numeral-plus-classifier phrases have relatively complex tone patterns in Naxi, Na (a.k.a. Mosuo) and Laze (a.k.a. Shuitian). These tone patterns have structural similarities across the three languages. Among the numerals from ‘1’ to ‘10’, three pairs emerge: ‘1’ and ‘2’ always have the same tonal behaviour; likewise, ‘4’ and ‘5’ share the same tone patterns, as do ‘6’ and ‘8’. Even those tone patterns that are irregular in view of the synchronic phonology of the languages at issue are no exception to the structural identity within these three pairs of numerals. These pairs also behave identically in numerals from ‘11’ to ‘99’ and above, e.g. ‘16’ and ‘18’ share the same tone pattern. In view of the paucity of irregular morphology—and indeed of morphological alternations in general—in these languages, these structural properties appear interesting for phylogenetic research. The identical behaviour of these pairs of numerals originates in morpho- phonological properties that they shared at least as early as the stage preceding the separation of Naxi, Na and Laze, referred to as the Proto-Naish stage. Although no reconstruction can be proposed as yet for these shared properties, it is argued that they provide a hint concerning the phylogenetic closeness of the three languages. Keywords: tone; numerals; classifiers; morpho-tonology; Naxi; Na; Mosuo; Laze; Muli Shuitian; Naish languages; phylogeny. 1. -

Syntactic Aspects of Nominalization in Five Tibeto-Burman Languages of the Himalayan Area1

Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area Volume 31.2 — October 2008 SYNTACTIC ASPECTS OF NOMINALIZATION IN FIVE TIBETO-BURMAN LANGUAGES OF THE HIMALAYAN AREA1 Carol Genetti University of California, Santa Barbara Research Centre for Linguistic Typology A.R. Coupe Ellen Bartee Kristine Hildebrandt You-Jing Lin La Trobe University SIL SIUE UC Santa Barbara The goal of this paper is to describe some of the syntactic structures that are created through nominalization processes in Himalayan Tibeto-Burman languages and the relationships between those structures. These include both structures involving the nominalization of clauses (e.g. complement clauses, relative clauses) and structures involving the nominalization of verbs and predicates (e.g. the derivation of nouns and adjectives). We will argue that, synchronically, clausal nominalization, structurally represented as [clause]NP, is the basic structure underlying many of the nominalizing constructions in these languages, even though individual constructions embed and alter this structure in interesting ways. In addition to clausal nominalization, we will illustrate the presence of derivational nominalization, represented as [V-NOM]N and [V-NOM]ADJ, although some nominal derivations target the predicate, not the verb root as their domain. We will also demonstrate that derivational nominalization can be seen as having developed from clausal nominalization, at least for some forms in some languages, and that the opposite direction of development, from derivational to clausal structures, is also attested. We will conclude with some syntactic observations pertinent to recent claims made on the historical relationship between nominalization and relativization, demonstrating that there are various ways that these structures can be related. -

Himalayan Linguistics the Encoding Of

Himalayan Linguistics The encoding of space in Manange and Nar-Phu (Tamangic) Kristine A. Hildebrandt Southern Illinois University Edwardsville ABSTRACT This is an account of the forms and semantic dimensions of spatial relations in Manange (Tibeto-Burman, Tamangic; Nepal), with comparison to sister language Nar-Phu. Topological relations (“IN/ON/AT/ NEAR”) in these languages are encoded by locative enclitics and also by a set of noun-like objects termed as “locational nouns.” In Manange, the general locative enclitic is more frequently encountered for a wide range of topological relations, while in Nar-Phu, the opposite pattern is observed, i.e. more frequent use of locational nouns. While the linguistic frame of reference system encoded in these forms is primarily relative (i.e. oriented on the speaker’s own viewing perspective), a more extrinsic/absolute system emerges with certain verbs of motion in these languages, with verbs like “come,” “go,” and certain verbs of placement or posture orienting to arbitrary fixed bearings such as slope. This account also provides some examples of cultural or metaphorical extensions of spatial forms as they are encountered in connected speech. KEYWORDS Tamangic, directional, static, dynamic, locational noun, relative, intrinsic, absolute This is a contribution from Himalayan Linguistics, Vol. 16(1), Special Issue on the Grammatical Encoding of Space, Carol Genetti and Kristine Hildebrandt (eds.): 41-58. ISSN 1544-7502 © 2017. All rights reserved. This Portable Document Format (PDF) file may not be altered in any way. Tables of contents, abstracts, and submission guidelines are available at escholarship.org/uc/himalayanlinguistics Himalayan Linguistics, Vol. 16(1). -

"Brightening" and the Place of Xixia (Tangut)

1 "Briiighttteniiing" and ttthe plllace of Xiiixiiia (Tanguttt) iiin ttthe Qiiiangiiic branch of Tiiibettto-Burman* James A. Matisoff University of California, Berkeley 1.0 Introduction Xixia (Tangut) is an extinct Tibeto-Burman language, once spoken in the Qinghai/Gansu/Tibetan border region in far western China. Its complex logographic script, invented around A.D. 1036, was the vehicle for a considerable body of literature until it gradually fell out of use after the Mongol conquest in 1223 and the destruction of the Xixia kingdom.1 A very large percentage of the 6000+ characters have been semantically deciphered and phonologically reconstructed, thanks to a Xixia/Chinese glossary, Tibetan transcriptions, and monolingual Xixia dictionaries and rhyme-books. The f«anqi\e method of indicating the pronunciation of Xixia characters was used both via other Xixia characters (in the monolingual dictionaries) and via Chinese characters (in the bilingual glossary Pearl in the Palm, where Chinese characters are also glossed by one or more Xixia ones). Various reconstruction systems have been proposed by scholars, including M.V. Sofronov/K.B. Keping, T. Nishida, Li Fanwen, and Gong Hwang-cherng. This paper relies entirely on the reconstructions of Gong.2 After some initial speculations that Xixia might have belonged to the Loloish group of Tibeto-Burman languages, scholarly opinion has now coalesced behind the geographically plausible opinion that it was a member of the "Qiangic" subgroup of TB. The dozen or so Qiangic languages, spoken in Sichuan Province and adjacent parts of Yunnan, were once among the most obscure in the TB family, loosely lumped together as the languages of the Western Barbarians (Xifan = Hsifan). -

Sino-Tibetan Languages 393

Sino-Tibetan Languages 393 Gair J W (1998). Studies in South Asian linguistics: Sinhala Government Press. [Reprinted Sri Lanka Sahitya and other South Asian languages. Oxford: Oxford Uni- Mandalaya, Colombo: 1962.] versity Press. Karunatillake W S (1992). An introduction to spoken Sin- Gair J W & Karunatillake W S (1974). Literary Sinhala. hala. Colombo: Gunasena. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University South Asia Program. Karunatillake W S (2001). Historical phonology of Sinha- Gair J W & Karunatillake W S (1976). Literary Sinhala lese: from old Indo-Aryan to the 14th century AD. inflected forms: a synopsis with a transliteration guide to Colombo: S. Godage and Brothers. Sinhala script. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University South Asia Macdougall B G (1979). Sinhala: basic course. Program. Washington D.C.: Foreign Service Institute, Department Gair J W & Paolillo J C (1997). Sinhala (Languages of the of State. world/materials 34). Mu¨ nchen: Lincom. Matzel K & Jayawardena-Moser P (2001). Singhalesisch: Gair J W, Karunatillake W S & Paolillo J C (1987). Read- Eine Einfu¨ hrung. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ings in colloquial Sinhala. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Reynolds C H B (ed.) (1970). An anthology of Sinhalese South Asia Program. literature up to 1815. London: George Allen and Unwin Geiger W (1938). A grammar of the Sinhalese language. (English translations). Colombo: Royal Asiatic Society. Reynolds C H B (ed.) (1987). An anthology of Sinhalese Godakumbura C E (1955). Sinhalese literature. Colombo: literature of the twentieth century. Woodchurch, Kent: Colombo Apothecaries Ltd. Paul Norbury/Unesco (English translations). Gunasekara A M (1891). A grammar of the Sinhalese Reynolds C H B (1995). Sinhalese: an introductory course language. -

Sino-Tibetan Numeral Systems: Prefixes, Protoforms and Problems

Sino-Tibetan numeral systems: prefixes, protoforms and problems Matisoff, J.A. Sino-Tibetan Numeral Systems: Prefixes, Protoforms and Problems. B-114, xii + 147 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1997. DOI:10.15144/PL-B114.cover ©1997 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS FOUNDING EDITOR: Stephen A. Wunn EDITORIAL BOARD: Malcolm D. Ross and Darrell T. Tryon (Managing Editors), Thomas E. Dutton, Nikolaus P. Himmelmann, Andrew K. Pawley Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in linguistic descriptions, dictionaries, atlases and other material on languages of the Pacific, the Philippines, Indonesia and southeast Asia. The authors and editors of Pacific Linguistics publications are drawn from a wide range of institutions around the world. Pacific Linguistics is associated with the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at the Australian National University. Pacific Linguistics was established in 1963 through an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund. It is a non-profit-making body financed largely from the sales of its books to libraries and individuals throughout the world, with some assistance from the School. The Editorial Board of Pacific Linguistics is made up of the academic staff of the School's Department of Linguistics. The Board also appoints a body of editorial advisors drawn from the international community of linguists. Publications in Series A, B and C and textbooks in Series D are refereed by scholars with re levant expertise who are normally not members of the editorial board. -

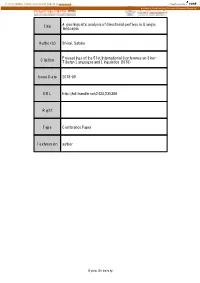

Title Rethinking the Orientational Prefixes in Rgyalrongic Languages

Rethinking the orientational prefixes in Rgyalrongic languages: Title The case of Siyuewu Khroskyabs Author(s) Lai, Yunfan; Wu, Mei-Shin; List, Johann-Mattis Proceedings of the 51st International Conference on Sino- Citation Tibetan Languages and Linguistics (2018) Issue Date 2018-09 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/235288 Right Type Conference Paper Textversion author Kyoto University Computer-Assisted Language Comparison CALC http://calc.digling.org Rethinking the orientational prefixes in Rgyalrongic languages: The case of Siyuewu Khroskyabs Yunfan Lai* with contributions by Mei-Shin Wu* and Johann-Mattis List* July 2018 1 Background Information 1.1 Rgyalrongic languages • Rgyalrongic is a group of Burmo-Qiangic languages in the Sino-Tibetan family mainly spoken in Western Sichuan, including Rgyalrong languages (Situ, Tshob- dun, Japhug and Zbu), Horpa languages and Khroskyabs dialects (Sun, 2000b,a). • Figure 1 shows the location of the languages under analysis. • These languages are highly complex both phonologically and morphologically. • Verbal morphology in Rgyalrongic, in particular, exhibits extraordinary affixation and various morphological processes. Computer-Assisted* Language Comparison (CALC), Department of Linguistic and Cultural Evolu- tion, Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History 1 Figure 1: Location of Rgyalrongic languages N 27.5 30.0 32.5 0 100 200 km 100 105 110 1.2 Orientational prefixes in Rgyalrongic languages • Burmo-Qiangic languages: “orientational prefixes” or “directional prefixes” (LaPolla, 2017). • Two major functions – Indicating the directions to which the action denoted by the verb (if applicable) – Lexically assigned to verb stems to indicate TAME properties. 1.3 Goal of the paper This paper will focus the first function of orientational prefixes in one of the Rgyalrongic languages, namely Siyuewu Khroskyabs, by re-examining the traditional approaches and providing an alternative way to analyse them. -

Title a Geolinguistic Analysis of Directional Prefixes In

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository A geolinguistic analysis of directional prefixes in Qiangic Title languages Author(s) Shirai, Satoko Proceedings of the 51st International Conference on Sino- Citation Tibetan Languages and Linguistics (2018) Issue Date 2018-09 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/235306 Right Type Conference Paper Textversion author Kyoto University A geolinguistic analysis of directional prefixes in Qiangic languages Satoko Shirai Japan Society for the Promotion of Science/University of Tsukuba 1 Introduction The Qiangic branch of languages are still under discussion with respect to their genealogical details such as its subclassification and position in Tibeto-Burman/Sino-Tibetan languages (Sun 1982, 1983, 2001, 2016; Thurgood 1985; Nishida 1987; Matisoff 2003; Jacques and Michaud 2011; Chirkova 2012). Although it is difficult to find shared phonological innovation in these languages, 1 they share plenty of typological characteristics such as a set of verbal prefixes to indicate the direction of movement (“directional prefixes”). Moreover, certain such typological characteristics including directional prefixes are also found in neighboring languages such as Pema, a Bodic language. This study examines the geographical distribution and relative chronology of representative directional prefixes in Qiangic languages: (i) “upward” (‘UPW’); (ii) “downward” (‘DWN’); (iii) “inward” (‘INW’), “upriver” (‘URV’), “eastward” (‘ES’), and so on; and (iv) “outward” (‘OUT’), “downriver” (‘DRV’), “westward” (‘WS’), and so on.2 Note that I not only examine single morphemes such as in (i) and (ii) but also examine a group of directional prefixes shown in (iii) and (iv), because of their semantic shifts. -

Report on the 19 Himalayan Languages Symposium

Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area Volume 36.2 — October 2013 REPORT ON THE 19TH HIMALAYAN LANGUAGES SYMPOSIUM AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY, CANBERRA, AUSTRALIA 6 SEPTEMBER - 8 SEPTEMBER, 2013 André Bosch Australian National University Peter Appleby Christopher Weedall Australian National University Australian National University In what was a highly successful series of intellectual discussions, smoothly organized by the team from the School of Culture, History and Languages at the Australian National University, Canberra, this year’s Himalayan Languages Symposium was the nineteenth since its inception in 1995. A small but energized group of linguists came from every corner of the globe to meet in Canberra, Australia, including many from the nations that play host to these diverse and fascinating languages, including Nepal and India. This was thanks to grants provided by the ANU to assist academics from developing nations in making the long journey to Canberra. Following a warm welcome to the Australian National University in the opening remarks, the first plenary talk was given by Toni Huber, discussing an ethnographic perspective on the linguistic work being done in eastern Bhutan and far west Arunachal Pradesh. In this talk Huber presented case studies of ritual and kinship in the area, particularly amongst the East Bodish area, showing how linguistic evidence can be used in ethnographic study and how, in turn, ethno- graphic work can inform linguistic study. Sessions bifurcated after the first plenary. In one session, a group discussed the sub-groupings of the Tibeto-Burman languages of Nepal. Isao Honda gave a thorough new perspective on the position of Kaike, having rejected its grouping among the Tamangic languages, while Kwang-Ju Cho gave an explanation for the current dialectal differences of Bantawa through diachronic analysis and contact with Nepali. -

25-Hyslop-Stls-2016-Handout

STLS-2016 University of Washington 10 September 2016 East Bodish reconstructions in a comparative light1 Gwendolyn Hyslop The University of Sydney [email protected] 1. Introduction 2. Overview of East Bodish 3. Pronouns 4. Crops 5. Body parts 6. Animals 7. Natural world 8. Material culture 9. Numerals 10. Verbs 11. Summary & Conclusions 1. Introduction 1.1. Aims • Present latest East Bodish (EB) reconstructions • Separate EB retentions from innovations • Compare EB with Tibetan, Tangut, Qiangic, rGyalrongic, Nungic, Burmish, to o aid the reconstruction as appropriate; and o possibly identify shared EB/Tibetic innovations; and o ultimately forward our understanding of the placement of EB and Tibeto-Burman2 phylogeny more broadly 1.2. Data and methodology • Tibetan: as cited • Tangut (STEDT 3.1) • Qiangic (STEDT 3.2) • rGyalrongic (STEDT 3.3) • Nungic (STEDT 4) • Burmish = Nisoic = Lolo-Burmese (STEDT 6 Lolo-Burmese-Naxi) • Note that I am not consistently accepting the proposed PTB reconstructions and their proposed reflexes (to be refined later); rather, I am using them as a guiding point to consider possible relationships. • I only list potential cognates. A ‘-’ indicates that no potential cognate was found (either because no word was reported or the words found were too different to be included here) 1 This work has been funded by an Australian Research Council Discovery Project (DP140103937). I am also grateful to the Dzongkha Development Commission in Bhutan, for supporting this research, and to Karma Tshering and Sonam Deki for helping to collect the data that have contributed to the reconstructions. 2 I am using the term Tibeto-Burman here to be interchangeable with Sino-Tibetan or Trans-Himalayan and do not mean to make any claims about the groupings within the family. -

Origins of Vowel Pharyngealization in Hongyan Qiang*

Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area Volume 29.2 — October 2006 ORIGINS OF VOWEL PHARYNGEALIZATION IN HONGYAN QIANG* Jonathan Evans Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica Hongyan, a variety of Northern Qiang (Tibeto-Burman, China) has four plain vowel monophthongs /i, u, ə, a/. Vowels may be lengthened, rhotacized, or pharyngealized, resulting in fourteen short and ten long vowel phonemes. No other varieties of Qiang have been described with pharyngealization, although the other suprasegmental effects are common throughout Northern Qiang. This paper explores how the distinctions which in Hongyan are made by differences in pharyngealization are phonologized in other varieties of Northern and Southern Qiang. Comparisons are drawn with processes in other Qiangic languages and with Proto-Tibeto- Burman reconstructions, in order to explore possible routes of development of pharyngealization; the most plausible source of pharyngealization seen thus far is retraction of vowels following PTB *-w-. Keywords: Qiang, pharyngealization, brightening, Tibeto-Burman. * Special thanks to the suggestions and help of David Bradley, Zev Handel, Randy LaPolla, James Matisoff, John Ohala, and Jackson Sun. They do not necessarily agree with all of the conclusions drawn herein. Thanks to Chenglong Huang, linguist and native Qiang speaker, for providing Ronghong Yadu data, analysis, and discussion. This research was supported by my home institution, and by a grant from the National Science Council of Taiwan (94-2411-H-001-071). 95 96 Jonathan Evans 1. INTRODUCTION TO HONGYAN Qiang (羌) is a Tibeto-Burman language spoken in the Aba Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture (啊壩藏族羌藏族自治州) of Sichuan Province, China. It has been divided into two major dialects, Northern (NQ) and Southern (SQ) by H. -

Reconsidering the Diachrony of Tone in Rma1

Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society JSEALS Vol. 13.1 (2020): 53-85 ISSN: 1836-6821, DOI: http://hdl.handle.net/10524/52460 University of Hawaiʼi Press RECONSIDERING THE DIACHRONY OF TONE IN RMA1 Nathaniel A. Sims University of California Santa Barbara [email protected] Abstract Prior work has suggested that proto-Rma was a non-tonal language and that tonal varieties underwent tonogenesis (Liú 1998, Evans 2001a-b). This paper re-examines the different arguments for the tonogenesis hypothesis and puts forward subgroup-internal and subgroup- external evidence for an alternative scenario in which tone, or its phonetic precursors, was present at the stage of proto-Rma. The subgroup-internal evidence comes from regular correspondences between tonal varieties. These data allow us to put forward a working hypothesis that proto-Rma had a two-way tonal contrast. Furthermore, existing accounts of how tonogenesis occurred in the tonal varieties are shown to be problematic. The subgroup-external evidence comes from regular tonal correspondences to two closely related tonal Trans- Himalayan subgroups: Prinmi, a modern language, and Tangut, a mediaeval language attested by written records from the 11th to 16th centuries. Regular correspondences among the tonal categories of these three subgroups, combined with the Rma-internal evidence, allow us to more confidently reconstruct tone for proto-Rma. Keywords: Tonogenesis, Trans-Himalayan (Sino-Tibetan), Rma, Prinmi, Tangut, Historical linguistics ISO 639-3 codes: qxs, pmi, pmj, txg 1. Introduction This paper addresses the diachrony of tone in Rma,2 a group of northeastern Trans-Himalayan3 language varieties spoken in 四川 Sìchuān, China.