On the Position of Baima Within Tibetan: a Look from Basic Vocabulary Ekaterina Chirkova

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE TONES of NUMERALS and NUMERAL-PLUS-CLASSIFIER PHRASES: on STRUCTURAL SIMILARITIES BETWEEN NAXI, NA and LAZE* Alexis Michaud LACITO-CNRS

Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area Volume 34.1 — April 2011 THE TONES OF NUMERALS AND NUMERAL-PLUS-CLASSIFIER PHRASES: ON STRUCTURAL SIMILARITIES BETWEEN NAXI, NA AND LAZE* Alexis Michaud LACITO-CNRS Abstract: Numeral-plus-classifier phrases have relatively complex tone patterns in Naxi, Na (a.k.a. Mosuo) and Laze (a.k.a. Shuitian). These tone patterns have structural similarities across the three languages. Among the numerals from ‘1’ to ‘10’, three pairs emerge: ‘1’ and ‘2’ always have the same tonal behaviour; likewise, ‘4’ and ‘5’ share the same tone patterns, as do ‘6’ and ‘8’. Even those tone patterns that are irregular in view of the synchronic phonology of the languages at issue are no exception to the structural identity within these three pairs of numerals. These pairs also behave identically in numerals from ‘11’ to ‘99’ and above, e.g. ‘16’ and ‘18’ share the same tone pattern. In view of the paucity of irregular morphology—and indeed of morphological alternations in general—in these languages, these structural properties appear interesting for phylogenetic research. The identical behaviour of these pairs of numerals originates in morpho- phonological properties that they shared at least as early as the stage preceding the separation of Naxi, Na and Laze, referred to as the Proto-Naish stage. Although no reconstruction can be proposed as yet for these shared properties, it is argued that they provide a hint concerning the phylogenetic closeness of the three languages. Keywords: tone; numerals; classifiers; morpho-tonology; Naxi; Na; Mosuo; Laze; Muli Shuitian; Naish languages; phylogeny. 1. -

An Internal Reconstruction of Tibetan Stem Alternations1

Transactions of the Philological Society Volume 110:2 (2012) 212–224 AN INTERNAL RECONSTRUCTION OF TIBETAN STEM ALTERNATIONS1 By GUILLAUME JACQUES CNRS (CRLAO), EHESS ABSTRACT Tibetan verbal morphology differs considerably from that of other Sino-Tibetan languages. Most of the vocalic and consonantal alternations observed in the verbal paradigms remain unexplained after more than a hundred years of investigation: the study of historical Tibetan morphology would seem to have reached an aporia. This paper proposes a new model, explaining the origin of the alternations in the Tibetan verb as the remnant of a former system of directional prefixes, typologically similar to the ones still attested in the Rgyalrongic languages. 1. INTRODUCTION Tibetan verbal morphology is known for its extremely irregular conjugations. Li (1933) and Coblin (1976) have successfully explained some of the vocalic and consonantal alternations in the verbal system as the result of a series of sound changes. Little substantial progress has been made since Coblin’s article, except for Hahn (1999) and Hill (2005) who have discovered two additional conjugation patterns, the l- and r- stems respectively. Unlike many Sino-Tibetan languages (see for instance DeLancey 2010), Tibetan does not have verbal agreement, and its morphology seems mostly unrelated to that of other languages. Only three morphological features of the Tibetan verbal system have been compared with other languages. First, Shafer (1951: 1022) has proposed that the a ⁄ o alternation in the imperative was related to the –o suffix in Tamangic languages. This hypothesis is well accepted, though Zeisler (2002) has shown that the so-called imperative (skul-tshig) was not an imperative at all but a potential in Old Tibetan. -

Review of Evidential Systems of Tibetan Languages

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2017 Review of Lauren Gawne Nathan W. Hill (eds.). 2016. Evidential systems of Tibetan languages. Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area 40(2), 285–303 Widmer, Manuel DOI: https://doi.org/10.1075/ltba.00002.wid Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-168681 Journal Article Accepted Version Originally published at: Widmer, Manuel (2017). Review of Lauren Gawne Nathan W. Hill (eds.). 2016. Evidential systems of Tibetan languages. Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area 40(2), 285–303. Linguistics of the Tibeto- Burman Area, 40(2):285-303. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1075/ltba.00002.wid Review of Evidential systems of Tibetan languages Gawne, Lauren & Nathan W. Hill (eds.). 2016. Evidential systems of Tibetan languages. de Gruyter: Berlin. vi + 472 pp. ISBN 978-3-11-047374-2 Reviewed by Manuel Widmer 1 Tibetan evidentiality systems and their relevance for the typology of evidentiality The evidentiality1 systems of Tibetan languages rank among the most complex in the world. According to Tournadre & Dorje (2003: 110), the evidentiality systeM of Lhasa Tibetan (LT) distinguishes no less than four “evidential Moods”: (i) egophoric, (ii) testiMonial, (iii) inferential, and (iv) assertive. If one also takes into account the hearsay Marker, which is cOMMonly considered as an evidential category in typological survey studies (e.g. Aikhenvald 2004; Hengeveld & Dall’Aglio Hattnher 2015; inter alia), LT displays a five-fold evidential distinction. The LT systeM, however, is clearly not the Most cOMplex of its kind within the Tibetan linguistic area. -

"Brightening" and the Place of Xixia (Tangut)

1 "Briiighttteniiing" and ttthe plllace of Xiiixiiia (Tanguttt) iiin ttthe Qiiiangiiic branch of Tiiibettto-Burman* James A. Matisoff University of California, Berkeley 1.0 Introduction Xixia (Tangut) is an extinct Tibeto-Burman language, once spoken in the Qinghai/Gansu/Tibetan border region in far western China. Its complex logographic script, invented around A.D. 1036, was the vehicle for a considerable body of literature until it gradually fell out of use after the Mongol conquest in 1223 and the destruction of the Xixia kingdom.1 A very large percentage of the 6000+ characters have been semantically deciphered and phonologically reconstructed, thanks to a Xixia/Chinese glossary, Tibetan transcriptions, and monolingual Xixia dictionaries and rhyme-books. The f«anqi\e method of indicating the pronunciation of Xixia characters was used both via other Xixia characters (in the monolingual dictionaries) and via Chinese characters (in the bilingual glossary Pearl in the Palm, where Chinese characters are also glossed by one or more Xixia ones). Various reconstruction systems have been proposed by scholars, including M.V. Sofronov/K.B. Keping, T. Nishida, Li Fanwen, and Gong Hwang-cherng. This paper relies entirely on the reconstructions of Gong.2 After some initial speculations that Xixia might have belonged to the Loloish group of Tibeto-Burman languages, scholarly opinion has now coalesced behind the geographically plausible opinion that it was a member of the "Qiangic" subgroup of TB. The dozen or so Qiangic languages, spoken in Sichuan Province and adjacent parts of Yunnan, were once among the most obscure in the TB family, loosely lumped together as the languages of the Western Barbarians (Xifan = Hsifan). -

Herever Possible

Published by Department of Information and International Relations (DIIR) Central Tibetan Administration Dharamshala-176215 H.P. India Email: [email protected] www.tibet.net Copyright © DIIR 2018 First edition: October 2018 1000 copies ISBN-978-93-82205-12-8 Design & Layout: Kunga Phuntsok / DIIR Printed at New Delhi: Norbu Graphics CONTENTS Foreword------------------------------------------------------------------1 Chapter One: Burning Tibet: Self-immolation Protests in Tibet---------------------5 Chapter Two: The Historical Status of Tibet-------------------------------------------37 Chapter Three: Human Rights Situation in Tibet--------------------------------------69 Chapter Four: Cultural Genocide in Tibet--------------------------------------------107 Chapter Five: The Tibetan Plateau and its Deteriorating Environment---------135 Chapter Six: The True Nature of Economic Development in Tibet-------------159 Chapter Seven: China’s Urbanization in Tibet-----------------------------------------183 Chapter Eight: China’s Master Plan for Tibet: Rule by Reincarnation-------------197 Chapter Nine: Middle Way Approach: The Way Forward--------------------------225 FOREWORD For Tibetans, information is a precious commodity. Severe restric- tions on expression accompanied by a relentless disinformation campaign engenders facts, knowledge and truth to become priceless. This has long been the case with Tibet. At the time of the publication of this report, Tibet has been fully oc- cupied by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) for just five months shy of sixty years. As China has sought to develop Tibet in certain ways, largely economically and in Chinese regions, its obsessive re- strictions on the flow of information have only grown more intense. Meanwhile, the PRC has ready answers to fill the gaps created by its information constraints, whether on medieval history or current growth trends. These government versions of the facts are backed ever more fiercely as the nation’s economic and military power grows. -

Sino-Tibetan Languages 393

Sino-Tibetan Languages 393 Gair J W (1998). Studies in South Asian linguistics: Sinhala Government Press. [Reprinted Sri Lanka Sahitya and other South Asian languages. Oxford: Oxford Uni- Mandalaya, Colombo: 1962.] versity Press. Karunatillake W S (1992). An introduction to spoken Sin- Gair J W & Karunatillake W S (1974). Literary Sinhala. hala. Colombo: Gunasena. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University South Asia Program. Karunatillake W S (2001). Historical phonology of Sinha- Gair J W & Karunatillake W S (1976). Literary Sinhala lese: from old Indo-Aryan to the 14th century AD. inflected forms: a synopsis with a transliteration guide to Colombo: S. Godage and Brothers. Sinhala script. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University South Asia Macdougall B G (1979). Sinhala: basic course. Program. Washington D.C.: Foreign Service Institute, Department Gair J W & Paolillo J C (1997). Sinhala (Languages of the of State. world/materials 34). Mu¨ nchen: Lincom. Matzel K & Jayawardena-Moser P (2001). Singhalesisch: Gair J W, Karunatillake W S & Paolillo J C (1987). Read- Eine Einfu¨ hrung. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ings in colloquial Sinhala. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Reynolds C H B (ed.) (1970). An anthology of Sinhalese South Asia Program. literature up to 1815. London: George Allen and Unwin Geiger W (1938). A grammar of the Sinhalese language. (English translations). Colombo: Royal Asiatic Society. Reynolds C H B (ed.) (1987). An anthology of Sinhalese Godakumbura C E (1955). Sinhalese literature. Colombo: literature of the twentieth century. Woodchurch, Kent: Colombo Apothecaries Ltd. Paul Norbury/Unesco (English translations). Gunasekara A M (1891). A grammar of the Sinhalese Reynolds C H B (1995). Sinhalese: an introductory course language. -

China (Includes Tibet, Hong Kong, and Macau) 2018 Human Rights Report

CHINA (INCLUDES TIBET, HONG KONG, AND MACAU) 2018 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The People’s Republic of China (PRC) is an authoritarian state in which the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is the paramount authority. CCP members hold almost all top government and security apparatus positions. Ultimate authority rests with the CCP Central Committee’s 25-member Political Bureau (Politburo) and its seven-member Standing Committee. Xi Jinping continued to hold the three most powerful positions as CCP general secretary, state president, and chairman of the Central Military Commission. Civilian authorities maintained control of security forces. During the year the government significantly intensified its campaign of mass detention of members of Muslim minority groups in the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region (Xinjiang). Authorities were reported to have arbitrarily detained 800,000 to possibly more than two million Uighurs, ethnic Kazakhs, and other Muslims in internment camps designed to erase religious and ethnic identities. Government officials claimed the camps were needed to combat terrorism, separatism, and extremism. International media, human rights organizations, and former detainees reported security officials in the camps abused, tortured, and killed some detainees. Human rights issues included arbitrary or unlawful killings by the government; forced disappearances by the government; torture by the government; arbitrary detention by the government; harsh and life-threatening prison and detention conditions; political prisoners; -

Sino-Tibetan Numeral Systems: Prefixes, Protoforms and Problems

Sino-Tibetan numeral systems: prefixes, protoforms and problems Matisoff, J.A. Sino-Tibetan Numeral Systems: Prefixes, Protoforms and Problems. B-114, xii + 147 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1997. DOI:10.15144/PL-B114.cover ©1997 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS FOUNDING EDITOR: Stephen A. Wunn EDITORIAL BOARD: Malcolm D. Ross and Darrell T. Tryon (Managing Editors), Thomas E. Dutton, Nikolaus P. Himmelmann, Andrew K. Pawley Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in linguistic descriptions, dictionaries, atlases and other material on languages of the Pacific, the Philippines, Indonesia and southeast Asia. The authors and editors of Pacific Linguistics publications are drawn from a wide range of institutions around the world. Pacific Linguistics is associated with the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at the Australian National University. Pacific Linguistics was established in 1963 through an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund. It is a non-profit-making body financed largely from the sales of its books to libraries and individuals throughout the world, with some assistance from the School. The Editorial Board of Pacific Linguistics is made up of the academic staff of the School's Department of Linguistics. The Board also appoints a body of editorial advisors drawn from the international community of linguists. Publications in Series A, B and C and textbooks in Series D are refereed by scholars with re levant expertise who are normally not members of the editorial board. -

Aphonologicalhistoryofamdotib

Bulletin of SOAS, 79, 2 (2016), 347–374. Ⓒ SOAS, University of London, 2016. doi:10.1017/S0041977X16000070 A Phonological History of Amdo Tibetan Rhymes* Xun G (author's draft) Centre de recherches linguistiques sur l'Asie orientale INALCO/CNRS/EHESS [email protected] Abstract In this study, a reconstruction is offered for the phonetic evolution of rhymes from Old Tibetan to modern-day Amdo Tibetan dialects. e rel- evant sound changes are proposed, along with their relative chronological precedence and the dating of some speci�c changes. Most interestingly, although Amdo Tibetan, identically to its ancestor Old Tibetan, does not have phonemic length, this study shows that Amdo Tibetan derives from an intermediate stage which, like many other Tibetan dialects, does make the distinction. 1 Introduction Amdo Tibetan, a dialect complex of closely related Tibetan varieties spoken in the Chinese provinces of Qinghai, Gansu and Sichuan, is, demographically, linguisti- cally and culturally, one of the most important dialects of Tibetan. e historical phonology of syllable onsets of Amdo Tibetan is well studied (Róna-Tas, 1966; Sun, 1987), notably for its fascinating retentions and innovations of the complex consonant clusters of Old Tibetan (OT). e rhymes (syllable nuclei and coda) have received less attention. *is work is related to the research strand PPC2 Evolutionary approaches to phonology: New goals and new methods (in diachrony and panchrony) of the Labex EFL (funded by the ANR/CGI). I would like to thank Guillaume Jacques and two anonymous reviewers for various suggestions which resulted in a more readable and better-argued paper. 1 is study aims to reconstruct the phonetic evolution of rhymes from Old Ti- betan1 to modern-day Amdo Tibetan dialects. -

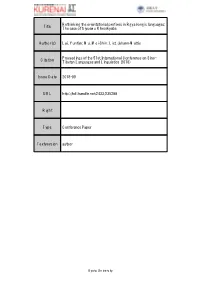

Title Rethinking the Orientational Prefixes in Rgyalrongic Languages

Rethinking the orientational prefixes in Rgyalrongic languages: Title The case of Siyuewu Khroskyabs Author(s) Lai, Yunfan; Wu, Mei-Shin; List, Johann-Mattis Proceedings of the 51st International Conference on Sino- Citation Tibetan Languages and Linguistics (2018) Issue Date 2018-09 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/235288 Right Type Conference Paper Textversion author Kyoto University Computer-Assisted Language Comparison CALC http://calc.digling.org Rethinking the orientational prefixes in Rgyalrongic languages: The case of Siyuewu Khroskyabs Yunfan Lai* with contributions by Mei-Shin Wu* and Johann-Mattis List* July 2018 1 Background Information 1.1 Rgyalrongic languages • Rgyalrongic is a group of Burmo-Qiangic languages in the Sino-Tibetan family mainly spoken in Western Sichuan, including Rgyalrong languages (Situ, Tshob- dun, Japhug and Zbu), Horpa languages and Khroskyabs dialects (Sun, 2000b,a). • Figure 1 shows the location of the languages under analysis. • These languages are highly complex both phonologically and morphologically. • Verbal morphology in Rgyalrongic, in particular, exhibits extraordinary affixation and various morphological processes. Computer-Assisted* Language Comparison (CALC), Department of Linguistic and Cultural Evolu- tion, Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History 1 Figure 1: Location of Rgyalrongic languages N 27.5 30.0 32.5 0 100 200 km 100 105 110 1.2 Orientational prefixes in Rgyalrongic languages • Burmo-Qiangic languages: “orientational prefixes” or “directional prefixes” (LaPolla, 2017). • Two major functions – Indicating the directions to which the action denoted by the verb (if applicable) – Lexically assigned to verb stems to indicate TAME properties. 1.3 Goal of the paper This paper will focus the first function of orientational prefixes in one of the Rgyalrongic languages, namely Siyuewu Khroskyabs, by re-examining the traditional approaches and providing an alternative way to analyse them. -

THE MEDIA's INFLUENCE on SUCCESS and FAILURE of DIALECTS: the CASE of CANTONESE and SHAAN'xi DIALECTS Yuhan Mao a Thesis Su

THE MEDIA’S INFLUENCE ON SUCCESS AND FAILURE OF DIALECTS: THE CASE OF CANTONESE AND SHAAN’XI DIALECTS Yuhan Mao A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Language and Communication) School of Language and Communication National Institute of Development Administration 2013 ABSTRACT Title of Thesis The Media’s Influence on Success and Failure of Dialects: The Case of Cantonese and Shaan’xi Dialects Author Miss Yuhan Mao Degree Master of Arts in Language and Communication Year 2013 In this thesis the researcher addresses an important set of issues - how language maintenance (LM) between dominant and vernacular varieties of speech (also known as dialects) - are conditioned by increasingly globalized mass media industries. In particular, how the television and film industries (as an outgrowth of the mass media) related to social dialectology help maintain and promote one regional variety of speech over others is examined. These issues and data addressed in the current study have the potential to make a contribution to the current understanding of social dialectology literature - a sub-branch of sociolinguistics - particularly with respect to LM literature. The researcher adopts a multi-method approach (literature review, interviews and observations) to collect and analyze data. The researcher found support to confirm two positive correlations: the correlative relationship between the number of productions of dialectal television series (and films) and the distribution of the dialect in question, as well as the number of dialectal speakers and the maintenance of the dialect under investigation. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author would like to express sincere thanks to my advisors and all the people who gave me invaluable suggestions and help. -

The Inclusive-Exclusive Distinction in Spoken and Written Tibetan

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kobe City University of Foreign Studies Institutional Repository 神戸市外国語大学 学術情報リポジトリ The Inclusive-Exclusive Distinction in Spoken and Written Tibetan 著者 Ebihara Shiho journal or Journal of Research Institute : Historical publication title Development of the Tibetan Languages volume 51 page range 85-102 year 2014-03-01 URL http://id.nii.ac.jp/1085/00001777/ Creative Commons : 表示 - 非営利 - 改変禁止 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/deed.ja The Inclusive-Exclusive Distinction in Spoken and Written Tibetan Shiho Ebihara Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa 1. Overview Filimonova (2005: ix) noted that “[t]he term[s] ‘inclusive’ and ‘exclusive’ are traditionally used to denote forms of personal pronouns which distinguish whether an addressee (or addressees) are included in or excluded from the set of referents which also contains the speaker.” Descriptive studies show that most spoken Tibetan languages feature the inclusive (INCL) - exclusive (EXCL) distinction in first- person plural and dual pronouns (except in Southern Tibetan). Furthermore, this distinction is also found in Old Tibetan and Middle Tibetan texts (as is pointed out in Zadoks 2004, Hill 2007, 2010). In this paper, we will first conduct an overview of the INCL-EXCL distinction in both spoken and written Tibetan. Then, based on this data, the following points will be discussed: 1) the classification of the INCL and EXCL forms of first-person pronouns, 2) the relations between these forms (of the two forms, which to identify as the default form for first-person pronouns), and 3) the historical development of INCL and EXCL first-person pronouns in Tibetan.