Evidential Systems of Tibetan Languages Trends in Linguistics Studies and Monographs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Bhutanese and Tibetan Dzongs **

ON BHUTANESE AND TIBETAN DZONGS ** Ingun Bruskeland Amundsen** “Seen from without, it´s a rocky escarpment! Seen from within, it´s all gold and treasure!”1 There used to be impressive dzong complexes in Tibet and areas of the Himalayas with Tibetan influence. Today most of them are lost or in ruins, a few are restored as museums, and it is only in Bhutan that we find the dzongs still alive today as administration centers and monasteries. This paper reviews some of what is known about the historical developments of the dzong type of buildings in Tibet and Bhutan, and I shall thus discuss towers, khars (mkhar) and dzongs (rdzong). The first two are included in this context as they are important in the broad picture of understanding the historical background and typological developments of the later dzongs. The etymological background for the term dzong is also to be elaborated. Backdrop What we call dzongs today have a long history of development through centuries of varying religious and socio-economic conditions. Bhutanese and Tibetan histories describe periods verging on civil and religious war while others were more peaceful. The living conditions were tough, even in peaceful times. Whatever wealth one possessed had to be very well protected, whether one was a layman or a lama, since warfare and strife appear to have been endemic. Security measures * Paper presented at the workshop "The Lhasa valley: History, Conservation and Modernisation of Tibetan Architecture" at CNRS in Paris Nov. 1997, and submitted for publication in 1999. ** Ingun B. Amundsen, architect MNAL, lived and worked in Bhutan from 1987 until 1998. -

7=SINO-INDIAN Phylosector

7= SINO-INDIAN phylosector Observatoire Linguistique Linguasphere Observatory page 525 7=SINO-INDIAN phylosector édition princeps foundation edition DU RÉPERTOIRE DE LA LINGUASPHÈRE 1999-2000 THE LINGUASPHERE REGISTER 1999-2000 publiée en ligne et mise à jour dès novembre 2012 published online & updated from November 2012 This phylosector comprises 22 sets of languages spoken by communities in eastern Asia, from the Himalayas to Manchuria (Heilongjiang), constituting the Sino-Tibetan (or Sino-Indian) continental affinity. See note on nomenclature below. 70= TIBETIC phylozone 71= HIMALAYIC phylozone 72= GARIC phylozone 73= KUKIC phylozone 74= MIRIC phylozone 75= KACHINIC phylozone 76= RUNGIC phylozone 77= IRRAWADDIC phylozone 78= KARENIC phylozone 79= SINITIC phylozone This continental affinity is composed of two major parts: the disparate Tibeto-Burman affinity (zones 70= to 77=), spoken by relatively small communities (with the exception of 77=) in the Himalayas and adjacent regions; and the closely related Chinese languages of the Sinitic set and net (zone 79=), spoken in eastern Asia. The Karen languages of zone 78=, formerly considered part of the Tibeto-Burman grouping, are probably best regarded as a third component of Sino-Tibetan affinity. Zone 79=Sinitic includes the outer-language with the largest number of primary voices in the world, representing the most populous network of contiguous speech-communities at the end of the 20th century ("Mainstream Chinese" or so- called 'Mandarin', standardised under the name of Putonghua). This phylosector is named 7=Sino-Indian (rather than Sino-Tibetan) to maintain the broad geographic nomenclature of all ten sectors of the linguasphere, composed of the names of continental or sub-continental entities. -

Vocabulary of Shingnyag Tibetan: a Dialect of Amdo Tibetan Spoken in Lhagang, Khams Minyag

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Prometheus-Academic Collections Asian and African Languages and Linguistics No.11, 2017 Vocabulary of Shingnyag Tibetan: A Dialect of Amdo Tibetan Spoken in Lhagang, Khams Minyag Suzuki, Hiroyuki IKOS, Universitetet i Oslo / National Museum of Ethnology Sonam Wangmo IKOS, Universitetet i Oslo Lhagang Town, located in Kangding Municipality, Ganzi Prefecture, Sichuan Province, China, is inhabited by many Tibetan pastoralists speaking varieties which are similar to Amdo Tibetan even though it is located at the Minyag Rabgang region of Khams, based on the Tibetan traditional geography. Among the multiple varieties spoken by inhabitants living in Lhagang Town, the Shingyag dialect is spoken in the south-western part of the town. It is somewhat different from other Amdo varieties spoken in Lhagang Town in the phonetic and phonological aspects. This article provides a word list with ca. 1500 words of Shingnyag Tibetan. Keywords: Amdo Tibetan, Minyag Rabgang, dialectology, migration pattern 1. Introduction 2. Phonological overview of Shingnyag Tibetan 3. Principal phonological features of Shingnyag Tibetan 1. Introduction This article aims to provide a word list (including ca. 1500 entries) with a phonological sketch of Shingnyag Tibetan, spoken in Xiya [Shing-nyag]1 Hamlet, located in the south-western part of Tagong [lHa-sgang] Town (henceforth Lhagang Town), Kangding [Dar-mdo] Municipality, Ganzi [dKar-mdzes] Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Sichuan Province, China (see Figure 1). Lhagang Town is in the easternmost part of Khams based on the traditional Tibetan geography, however, it is inhabited by many Tibetans whose mother tongue is Amdo Tibetan.2 Referring to Qu and Jin (1981), we can see that it is already known that Amdo-speaking Tibetans live in Suzuki, Hiroyuki and Sonam Wangmo. -

Tibetan Vwa 'Fox' and the Sound Change Tibeto

Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area Volume 29.2 — October 2006 TIBETAN VWA ‘FOX’ AND THE SOUND CHANGE TIBETO-BURMAN *WA > TIBETAN O Nathan W. Hill Harvard University Paul Benedict (1972: 34) proposed that Tibeto-Burman medial *-wa- regularly leads to -o- in Old Tibetan, but that initial *wa did not undergo this change. Because Old Tibetan has no initial w-, and several genuine words have the rhyme -wa, this proposal cannot be accepted. In particular, the intial of the Old Tibetan word vwa ‘fox’ is v- and not w-. འ Keywords: Old Tibetan, Tibeto-Burman, phonology. 1. INTRODUCTION The Tibetan word vwa ‘fox’ has received a certain amount of attention for being an exception to the theory that Tibeto-Burman *wa yields o in Tibetan1. The first formulation of this sound law known to me is Laufer’s statement “Das Barmanische besitzt nämlich häufig die Verbindung w+a, der ein tibetisches [sic] o oder u entspricht [Burmese namely frequently has the combination w+a, which corresponds to a Tibetan o or u]” (Laufer 1898/1899: part III, 224; 1976: 120). Laufer’s generalization was based in turn upon cognate sets assembled by Bernard Houghton (1898). Concerning this sound change, in his 1972 monograph, Paul Benedict writes: “Tibetan has initial w- only in the words wa ‘gutter’, wa ‘fox’ and 1 Here I follow the Wylie system of Tibetan transliteration with the exception that the letter (erroneously called a-chung by some) is written in the Chinese fashion འ as <v> rather than the confusing <’>. On the value of Written Tibetan v as [ɣ] cf. -

)53Lt- I'\.' -- the ENGLISH and FOREIGN LANGUAGES UNIVERSITY HYDERABAD 500605, INDIA

DZONGKHA SEGMENTS AND TONES: A PHONETIC AND PHONOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION KINLEY DORJEE . I Supervisor PROFESSOR K.G. VIJA Y AKRISHNAN Department of Linguistics and Contemporary English Hyderabad Co-supervisor Dr. T. Temsunungsang The English and Foreign Languages University Shillong Campus A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics SCHOOL OF LANGUAGE SCIENCES >. )53lt- I'\.' -- THE ENGLISH AND FOREIGN LANGUAGES UNIVERSITY HYDERABAD 500605, INDIA JULY 2011 To my mother ABSTRACT In this thesis, we make, for the first time, an acoustic investigation of supposedly unique phonemic contrasts: a four-way stop phonation contrast (voiceless, voiceless aspirated, voiced and devoiced), a three-way fricative contrast (voiceless, voiced and devoiced) and a two-way sonorant contrast (voiced and voiceless) in Dzongkha, a Tibeto-Burman language spoken in Western Bhutan. Paying special attention to the 'Devoiced' (as recorded in the literature) obstruent and the 'Voiceless' sonorants, we examine the durational and spectral characteristics, including the vowel quality (following the initial consonant types), in comparison with four other languages, viz .. Hindi. Korean (for obstruents), Mizo and Tenyidie (for sonorants). While the 'devoiced' phonation type in Dzongkha is not attested in any language in the region, we show that the devoiced type is very different from the 'breathy' phonation type, found in Hindi. However, when compared to the three-way voiceless stop phonation types (Tense, Lax and Aspirated) in Korean, we find striking similarities in the way the two stops CDevoiced' and 'Lax') employ their acoustic correlates. We extend our analysis of stops to fricatives, and analyse the three fricatives in Dzongkha as: Tense, Lax and Voiced. -

Review of Evidential Systems of Tibetan Languages

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2017 Review of Lauren Gawne Nathan W. Hill (eds.). 2016. Evidential systems of Tibetan languages. Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area 40(2), 285–303 Widmer, Manuel DOI: https://doi.org/10.1075/ltba.00002.wid Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-168681 Journal Article Accepted Version Originally published at: Widmer, Manuel (2017). Review of Lauren Gawne Nathan W. Hill (eds.). 2016. Evidential systems of Tibetan languages. Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area 40(2), 285–303. Linguistics of the Tibeto- Burman Area, 40(2):285-303. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1075/ltba.00002.wid Review of Evidential systems of Tibetan languages Gawne, Lauren & Nathan W. Hill (eds.). 2016. Evidential systems of Tibetan languages. de Gruyter: Berlin. vi + 472 pp. ISBN 978-3-11-047374-2 Reviewed by Manuel Widmer 1 Tibetan evidentiality systems and their relevance for the typology of evidentiality The evidentiality1 systems of Tibetan languages rank among the most complex in the world. According to Tournadre & Dorje (2003: 110), the evidentiality systeM of Lhasa Tibetan (LT) distinguishes no less than four “evidential Moods”: (i) egophoric, (ii) testiMonial, (iii) inferential, and (iv) assertive. If one also takes into account the hearsay Marker, which is cOMMonly considered as an evidential category in typological survey studies (e.g. Aikhenvald 2004; Hengeveld & Dall’Aglio Hattnher 2015; inter alia), LT displays a five-fold evidential distinction. The LT systeM, however, is clearly not the Most cOMplex of its kind within the Tibetan linguistic area. -

Day 1: Handouts (Tibet)

Handout One: Introducing Tibet [With Country Names] First, let’s look at this world map. Find the United States. Now let’s find China! Tibet is a region within China. This is a map of Tibet’s six prefectures and its capital city, Lhasa. On the map of China below, find Tibet. What color is Tibet on this map? Did you find it? [Teacher’s Key] Handout One: Introducing Tibet [Without Country Names] First, let’s look at this world map. Find the United States. Now let’s find China! Hint: It’s light green! Tibet is a region within China. This is a map of Tibet’s six prefectures and its capital city, Lhasa. On the map of China below, find Tibet. What color is Tibet on this map? Did you find it? [Teacher’s Key] Handout Two: Quick Facts about Tibet and the Tibet Autonomous Region ★ Tibet is historically made up of three provinces of Amdo, Kham and U-Tsang. It was split up by the People’s Republic of China. The main Tibetan region now is the Tibet Autonomous Region. ★ The Tibet Autonomous Region, is a province within the People’s Republic of China. ★ Before 1950, Tibet was an independent country, but China invaded the country and took over. ★ The capital of the Tibet Autonomous Region is Lhasa. ★ The official language of the Tibet Autonomous Region is Lhasa Tibetan. ○ In schools, children are also taught Mandarin Chinese. ★ The main religion among the Tibetan people is Tibetan Buddhism. ★ In 1959, the Dalai Lama and 80,000 Tibetans fled to India for their safety. -

A Guide to the Syuba (Kagate) Language Documentation Corpus

Vol. 12 (2018), pp. 204–234 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24768 Revised Version Received: 17 Jan 2018 A Guide to the Syuba (Kagate) Language Documentation Corpus Lauren Gawne SOAS University of London La Trobe University This article provides an overview of the collection “Kagate (Syuba)”, archived with both the Pacific and Regional Archive for Digital Sources in Endangered Cultures (PARADISEC) and the Endangered Language Archive (ELAR). It pro- vides an overview of the materials that have been archived, as well as details of the workflow, conventions used, and structure of the collection. It also provides context for the content of the collection, including an overview of the language context, and some of the motivations behind the documentation project. This article thus provides an entry point to the collection. The future plans for the collection – from the perspectives of both the researcher and Syuba speakers – are also outlined, but with the overwhelming majority of items in the collection available to others, it is hoped that this article will encourage use of the materials by other researchers. 1. Introduction Language documentation involves the development of corpora of materials from which descriptions of grammar and language use can be developed, alongside other uses of the materials by both speakers of the language and researchers. Himmelmann (1998) argues that language documentation and description are two distinct, but interrelated, activities. In reality, the majority of basic linguistic descrip- tion based on primary data is undertaken by the same person who collected the data. Very little of this descriptive work makes clear the nature of the data on which it is built; in a survey of 50 published grammars and 50 PhD dissertations, Gawne et al. -

PPD Talk by Prof. Nicolas Tournadre

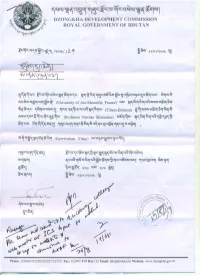

-. '" ~~Q.l·~~·q~~·~~~·~,,·rq·~,,·qt4Q.l·~~·l~~l DZONGKHA DEVELOPMENT COMMISSION ROYAL GOVERNMENT OF BHUTAN "'~=<~r\"~\"\~T"""""'" ..~ D. oN' qJ{, n..,~~V){"\ ..."."" ~ t ,. '" '" '" -.r '" 7::F. '" C\.. '" C\.. '" C\ '" '" '" ~.~~.~.u-yz:::..~z:::..(tI.~z:::..~t4QJ.~~.ct:l~~.~z:::~~·~·"~·~~z:::.·o-!sa·,,o-!·~z::r:Ir~~~·o-!~o-!·~r:;r·sa~·QJ~·.~~~.~.. ~".~QJ.~~~.QJ~.~r:;r.~. (University of Aix-Marseille, France) QJ~' ~~.~~.~~.t.lq.o-!(tI~.~~~.~~. C\..C\.. C\.. C\.. C\.. C\.. C\.. ",C\C\..C\.. ~~'~'~z:::.' ~~~~'r:;r~QJ'~' ~z:::.~·-o~·7·o-!·QJ·u-y~·~~·,,~~·(Tibeto-Bunnan) ~.~.~(tI~.~a:;~.-o~.~~.o-!. C\..-.r '" C\.. '" C\.. C\.. C\.. C\.. '" C\.. ~(tI~.~r:;rz:::..~."l.QJ.~".~~.~~.(Professor Nicolas 'J:oumadre) o-!a:;~'~~' ~~·u-y~·,,~·t.I~·~S·~~~·~· '" '" C\..'" C\..C\.. C\.. C\ '" '" sa~'QJ~' ~~.~.~~.~~.~. ~~z:::.·r:;r4~·~~z:::.·~·~~·o-!·~~·~z:::.·r~r~S~·~~z:::.·~·r:;r·o-!~~1r '" '" C\.. '" C\.. C\..-.r '" ~~z:::.·r:;r4~·~~·~~1 ~z:::..(tI.~z:::..a:;~.~~.~.~".~~.~~·o-!z:::.·o-!·u-y~·t.I~·~z:::.·~C4QJl ~'~~~1 ~z:::.'t.Iq·~'*r:;r·~~·t.lq·~r:;r·l~~·~·'1QJ·~i!~~·(tIz:::.l"l·'1:fz:::.'Sz:::.·~1a5.J·~~ ~l~l ~o-!'~l~' ~:~o QJ~' l{.:oo ~~l C\..~ a;~·:uz:::.~1 ~'a:l~' '.l...'.l...lo"I'.l...o'}~ ~l 4~·"r:;r·~QJ·o-!~~1 '" §z:::.·a:;~1 Phone: 322663/325226/325227/323721 Fax: 322992 P.O Box 122 Email: [email protected] Website: www.dzongkha.gov.bt Nicolas Tournadre's Curriculum Vitae Name: Nicolas Toumadre / '",?~.q~"'a:;~.~.q~~. Professor at the University of Aix-Marseille, linguistics department CN~~r~r"'- aI~:~llrmJ::r~ra5~'a,- ~l·~~II ""·qc:rc5~·~~ l~'ifl~"- 'a5~'aII E~ail : [email protected] Professional site: www.nicolas-tournadre.net Education 1984 MA in Russian Literature, Sorbonne University 1987 BA in Tibetan language and civilisation, Institute of Oriental Languages and Civilisation (INalco, Paris) 1989 Louis Forest prize-winning awarded by the "Chancellerie des Universites de Paris". -

Herever Possible

Published by Department of Information and International Relations (DIIR) Central Tibetan Administration Dharamshala-176215 H.P. India Email: [email protected] www.tibet.net Copyright © DIIR 2018 First edition: October 2018 1000 copies ISBN-978-93-82205-12-8 Design & Layout: Kunga Phuntsok / DIIR Printed at New Delhi: Norbu Graphics CONTENTS Foreword------------------------------------------------------------------1 Chapter One: Burning Tibet: Self-immolation Protests in Tibet---------------------5 Chapter Two: The Historical Status of Tibet-------------------------------------------37 Chapter Three: Human Rights Situation in Tibet--------------------------------------69 Chapter Four: Cultural Genocide in Tibet--------------------------------------------107 Chapter Five: The Tibetan Plateau and its Deteriorating Environment---------135 Chapter Six: The True Nature of Economic Development in Tibet-------------159 Chapter Seven: China’s Urbanization in Tibet-----------------------------------------183 Chapter Eight: China’s Master Plan for Tibet: Rule by Reincarnation-------------197 Chapter Nine: Middle Way Approach: The Way Forward--------------------------225 FOREWORD For Tibetans, information is a precious commodity. Severe restric- tions on expression accompanied by a relentless disinformation campaign engenders facts, knowledge and truth to become priceless. This has long been the case with Tibet. At the time of the publication of this report, Tibet has been fully oc- cupied by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) for just five months shy of sixty years. As China has sought to develop Tibet in certain ways, largely economically and in Chinese regions, its obsessive re- strictions on the flow of information have only grown more intense. Meanwhile, the PRC has ready answers to fill the gaps created by its information constraints, whether on medieval history or current growth trends. These government versions of the facts are backed ever more fiercely as the nation’s economic and military power grows. -

A Grammar of Bao'an Tu, a Mongolic Language Of

A GRAMMAR OF BAO’AN TU, A MONGOLIC LANGUAGE OF NORTHWEST CHINA by Robert Wayne Fried June 1, 2010 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Buffalo, State University of New York in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Linguistics UMI Number: 3407976 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3407976 Copyright 2010 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 Copyright by Robert Wayne Fried 2010 ii Acknowledgements I wish to express my deepest gratitude to my advisor, Matthew Dryer for his guidance and for his detailed comments on numerous drafts of this dissertation. I would also like to thank my committee members, Karin Michelson and Robert VanValin, Jr., for their patience, flexibility, and helpful feedback. I am grateful to have had the opportunity to be a part of the linguistics department at the University at Buffalo. I have benefited in ways too numerous to recount from my interactions with the UB linguistics faculty and with my fellow graduate students. I am also grateful for the tireless help of Carole Orsolitz, Jodi Reiner, and Sharon Sell, without whose help I could not have successfully navigated a study program spanning nine years and multiple international locations. -

Sino-Tibetan Languages 393

Sino-Tibetan Languages 393 Gair J W (1998). Studies in South Asian linguistics: Sinhala Government Press. [Reprinted Sri Lanka Sahitya and other South Asian languages. Oxford: Oxford Uni- Mandalaya, Colombo: 1962.] versity Press. Karunatillake W S (1992). An introduction to spoken Sin- Gair J W & Karunatillake W S (1974). Literary Sinhala. hala. Colombo: Gunasena. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University South Asia Program. Karunatillake W S (2001). Historical phonology of Sinha- Gair J W & Karunatillake W S (1976). Literary Sinhala lese: from old Indo-Aryan to the 14th century AD. inflected forms: a synopsis with a transliteration guide to Colombo: S. Godage and Brothers. Sinhala script. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University South Asia Macdougall B G (1979). Sinhala: basic course. Program. Washington D.C.: Foreign Service Institute, Department Gair J W & Paolillo J C (1997). Sinhala (Languages of the of State. world/materials 34). Mu¨ nchen: Lincom. Matzel K & Jayawardena-Moser P (2001). Singhalesisch: Gair J W, Karunatillake W S & Paolillo J C (1987). Read- Eine Einfu¨ hrung. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ings in colloquial Sinhala. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Reynolds C H B (ed.) (1970). An anthology of Sinhalese South Asia Program. literature up to 1815. London: George Allen and Unwin Geiger W (1938). A grammar of the Sinhalese language. (English translations). Colombo: Royal Asiatic Society. Reynolds C H B (ed.) (1987). An anthology of Sinhalese Godakumbura C E (1955). Sinhalese literature. Colombo: literature of the twentieth century. Woodchurch, Kent: Colombo Apothecaries Ltd. Paul Norbury/Unesco (English translations). Gunasekara A M (1891). A grammar of the Sinhalese Reynolds C H B (1995). Sinhalese: an introductory course language.