Hans Van Wees, University College London THUCYDIDES on EARLY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

Agorapicbk-17.Pdf

Excavations of the Athenian Agora Picture Book No. 17 Prepared by Mabel L. Lang Dedicated to Eugene Vanderpool o American School of Classical Studies at Athens ISBN 87661-617-1 Produced by the Meriden Gravure Company Meriden, Connecticut COVER: Bone figure of Socrates TITLE PAGE: Hemlock SOCRATES IN THE AGORA AMERICAN SCHOOL OF CLASSICAL STUDIES AT ATHENS PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY 1978 ‘Everything combines to make our knowledge of Socrates himself a subject of Socratic irony. The only thing we know definitely about him is that we know nothing.’ -L. Brunschvicg As FAR AS we know Socrates himselfwrote nothing, yet not only were his life and words given dramatic attention in his own time in the Clouds of Ar- istophanes, but they have also become the subject of many others’ writing in the centuries since his death. Fourth-century B.C. writers who had first-hand knowledge of him composed either dialogues in which he was the dominant figure (Plato and Aeschines) or memories of his teaching and activities (Xe- nophon). Later authors down even to the present day have written numerous biographies based on these early sources and considering this most protean of philosophers from every possible point of view except perhaps the topograph- ical one which is attempted here. Instead of putting Socrates in the context of 5th-century B.C. philosophy, politics, ethics or rhetoric, we shall look to find him in the material world and physical surroundings of his favorite stamping- grounds, the Athenian Agora. Just as ‘agora’ in its original sense meant ‘gathering place’ but came in time to mean ‘market place’, so the agora itself was originally a gathering place I. -

Archaic Eretria

ARCHAIC ERETRIA This book presents for the first time a history of Eretria during the Archaic Era, the city’s most notable period of political importance. Keith Walker examines all the major elements of the city’s success. One of the key factors explored is Eretria’s role as a pioneer coloniser in both the Levant and the West— its early Aegean ‘island empire’ anticipates that of Athens by more than a century, and Eretrian shipping and trade was similarly widespread. We are shown how the strength of the navy conferred thalassocratic status on the city between 506 and 490 BC, and that the importance of its rowers (Eretria means ‘the rowing city’) probably explains the appearance of its democratic constitution. Walker dates this to the last decade of the sixth century; given the presence of Athenian political exiles there, this may well have provided a model for the later reforms of Kleisthenes in Athens. Eretria’s major, indeed dominant, role in the events of central Greece in the last half of the sixth century, and in the events of the Ionian Revolt to 490, is clearly demonstrated, and the tyranny of Diagoras (c. 538–509), perhaps the golden age of the city, is fully examined. Full documentation of literary, epigraphic and archaeological sources (most of which have previously been inaccessible to an English-speaking audience) is provided, creating a fascinating history and a valuable resource for the Greek historian. Keith Walker is a Research Associate in the Department of Classics, History and Religion at the University of New England, Armidale, Australia. -

Ancient Greeks Victor Davis Hanson John Keegan, Series Editor

SMITHSONIAN HISTORY OF WARFARE WARS OF THE ANCIENT GREEKS VICTOR DAVIS HANSON JOHN KEEGAN, SERIES EDITOR () Smithsonian Books (::::Collins An Imprint ofHarperCollinsPub/ishers For W. K. Pritchett, who revolutionized the study of Ancient Greek warfare Text © 1999 by Victor Davis Hanson Design and layout© 1999 by Cassell & Co. First published in Great Britain 1999 The picture credits on page 240 constitute an extension to this copyright page. Material in the introduction and chapter 5 is based on ideas that appeared in Victor Davis Hanson and john Heath, Who Killed Homer? The Demise if Classical Education and the Recovery ifGreek Wisdom (The Free Press, New York, 1998) 'and Victor Davis Hanson, "Alexander the Kille1~" Quarterly journal ifMilitary History, spring 1998, I 0.3, 8-20. WARS OF THE ANCIENT GREEKS. All rights reserved. No part of this title may be reproduced or transmitted by any means (including photography or storing it in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright owner. For infor mation, address HarperCollins Publishers, 10 East 53rd Street, New York, NY 10022. Published 2004 in the United States of America by Smithsonian Books Acknowledgments In association with Cassell Wellington House, 125 Strand London WC2R OBB would like to thank John Keegan and Judith Flanders for asking me Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data I to write this volume on the Ancient Greeks at war. My colleague at Hanson, Victor Davis. California State University, Fresno, Professor Bruce Thornton, kindly Wars of the ancient Greeks I Victor Davis Hanson ; John Keegan, general editor. -

A View of the Horse from the Classical Perspective the Penn Museum Collection by Donald White

A View of the Horse from the Classical Perspective The Penn Museum Collection by donald white quus caballus is handsomely stabled in tive how-to manual On Horsemanship (“The tail and mane the University of Pennsylvania Museum of should be washed, to keep the hairs growing, as the tail is used Archaeology and Anthropology. From the to swat insects and the mane may be grabbed by the rider Chinese Rotunda’s masterpiece reliefs portray- more easily if long.”) all the way down to the 9th century AD ing two horses of the Chinese emperor Taizong Corpus of Greek Horse Veterinarians, which itemizes drugs for Eto Edward S. Curtis’s iconic American Indian photographs curing equine ailments as well as listing vets by name, Greek housed in the Museum’s Archives, horses stand with man and Roman literature is filled with equine references. One in nearly every culture and time-frame represented in the recalls the cynical utterance of the 5th century BC lyric poet Museum’s Collection (pre-Columbian America and the Xenophanes from the Asia Minor city of Colophon: “But if northern polar region being perhaps the two most obvious cattle and horses and lions had hands, or were able to do the exceptions). Examples drawn from the more than 30,000 work that men can, horses would draw the forms of the gods like Greek, Roman, and Etruscan vases, sculptures, and other horses” (emphasis added by author). objects in the Museum’s Mediterranean Section serve here as The partnership between horse and master in antiquity rested a lens through which to view some of the notable roles the on many factors; perhaps the most important was that the horse horse played in the classical Mediterranean world. -

Rethinking Athenian Democracy.Pdf

Rethinking Athenian Democracy A dissertation presented by Daniela Louise Cammack to The Department of Government in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Political Science Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts January 2013 © 2013 Daniela Cammack All rights reserved. Professor Richard Tuck Daniela Cammack Abstract Conventional accounts of classical Athenian democracy represent the assembly as the primary democratic institution in the Athenian political system. This looks reasonable in the light of modern democracy, which has typically developed through the democratization of legislative assemblies. Yet it conflicts with the evidence at our disposal. Our ancient sources suggest that the most significant and distinctively democratic institution in Athens was the courts, where decisions were made by large panels of randomly selected ordinary citizens with no possibility of appeal. This dissertation reinterprets Athenian democracy as “dikastic democracy” (from the Greek dikastēs, “judge”), defined as a mode of government in which ordinary citizens rule principally through their control of the administration of justice. It begins by casting doubt on two major planks in the modern interpretation of Athenian democracy: first, that it rested on a conception of the “wisdom of the multitude” akin to that advanced by epistemic democrats today, and second that it was “deliberative,” meaning that mass discussion of political matters played a defining role. The first plank rests largely on an argument made by Aristotle in support of mass political participation, which I show has been comprehensively misunderstood. The second rests on the interpretation of the verb “bouleuomai” as indicating speech, but I suggest that it meant internal reflection in both the courts and the assembly. -

1 Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer's Iliad Senior Thesis

Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer’s Iliad Senior Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Undergraduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Undergraduate Program in Classical Studies Professor Joel Christensen, Advisor In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts By Joana Jankulla May 2018 Copyright by Joana Jankulla 1 Copyright by Joana Jankulla © 2018 2 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Professor Joel Christensen. Thank you, Professor Christensen for guiding me through this process, expressing confidence in me, and being available whenever I had any questions or concerns. I would not have been able to complete this work without you. Secondly, I would like to thank Professor Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow and Professor Cheryl Walker for reading my thesis and providing me with feedback. The Classics Department at Brandeis University has been an instrumental part of my growth in my four years as an undergraduate, and I am eternally thankful to all the professors and staff members in the department. Thank you to my friends, specifically Erica Theroux, Sarah Jousset, Anna Craven, Rachel Goldstein, Taylor McKinnon and Georgie Contreras for providing me with a lot of emotional support this year. I hope you all know how grateful I am for you as friends and how much I have appreciated your love this year. Thank you to my mom for FaceTiming me every time I was stressed about completing my thesis and encouraging me every step of the way. Finally, thank you to Ian Leeds for dropping everything and coming to me each time I needed it. -

The Athenian Prytaneion Discovered? 35

HESPERIA 75 (2006) THE ATHENIAN Pages 33-81 PRYTANEION DISCOVERED? ABSTRACT The author proposes that the Athenian Prytaneion, one of the city's most important civic buildings, was located in the peristyle complex beneath Agia Aikaterini Square, near the ancient Street of the Tripods and theMonument of Lysikrates in the modern Plaka. This thesis, which is consistent with Pausa s nias topographical account of ancient Athens, is supported by archaeological and epigraphical evidence. The identification of the Prytaneion at the eastern foot of the Acropolis helps to reconstruct the map of Archaic and Classical Athens and illuminates the testimony of Herodotos and Thucydides. most The Prytaneion is the oldest and important of the civic buildings in to us ancient Athens that have remained lost until the present.1 For the or Athenians the Prytaneion, town hall, the office of the city's chief official, as a symbolized the foundation of Athens city-state, its construction form ing an integral part of Theseus's legendary synoecism of Attica (Thuc. 2.15.2; Plut. Thes. 24.3). Like other prytaneia throughout the Greek world, the Athenian Prytaneion represented what has been termed the very "life common of the polis," housing the hearth of the city, the "inextinguishable and immovable flame" of the goddess Hestia.2 As the ceremonial center was of Athens, the Prytaneion the site of both public entertainment for 1.1 am to the to a excellent for greatly indebted express my heartfelt thanks number suggestions improving this 1st Ephoreia of Prehistoric and Classi of scholars who have given generously article. -

Socrates and Democratic Athens: the Story of the Trial in Its Historical and Legal Contexts

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics Socrates and democratic Athens: The story of the trial in its historical and legal contexts. Version 1.0 July 2006 Josiah Ober Princeton University Abstract: Socrates was both a loyal citizen (by his own lights) and a critic of the democratic community’s way of doing things. This led to a crisis in 339 B.C. In order to understand Socrates’ and the Athenian community’s actions (as reported by Plato and Xenophon) it is necessary to understand the historical and legal contexts, the democratic state’s commitment to the notion that citizens are resonsible for the effects of their actions, and Socrates’ reasons for preferring to live in Athens rather than in states that might (by his lights) have had substantively better legal systems. Written for the Cambridge Companion to Socrates. © Josiah Ober. [email protected] Socrates and democratic Athens: The story of the trial in its historical and legal contexts. (for Cambridge Companion to Socrates) Josiah Ober, Princeton University Draft of August 2004 In 399 B.C. the Athenian citizen Socrates, son of Sophroniscus of the deme (township) Alopece, was tried by an Athenian court on the charge of impiety (asebeia). He was found guilty by a narrow majority of the empanelled judges and executed in the public prison a few days later. The trial and execution constitute the best documented events in Socrates’ life and a defining moment in the relationship between Greek philosophy and Athenian democracy. Ever since, philosophers and historians have sought to -

Thales of Miletus Sources and Interpretations Miletli Thales Kaynaklar Ve Yorumlar

Thales of Miletus Sources and Interpretations Miletli Thales Kaynaklar ve Yorumlar David Pierce October , Matematics Department Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University Istanbul http://mat.msgsu.edu.tr/~dpierce/ Preface Here are notes of what I have been able to find or figure out about Thales of Miletus. They may be useful for anybody interested in Thales. They are not an essay, though they may lead to one. I focus mainly on the ancient sources that we have, and on the mathematics of Thales. I began this work in preparation to give one of several - minute talks at the Thales Meeting (Thales Buluşması) at the ruins of Miletus, now Milet, September , . The talks were in Turkish; the audience were from the general popu- lation. I chose for my title “Thales as the originator of the concept of proof” (Kanıt kavramının öncüsü olarak Thales). An English draft is in an appendix. The Thales Meeting was arranged by the Tourism Research Society (Turizm Araştırmaları Derneği, TURAD) and the office of the mayor of Didim. Part of Aydın province, the district of Didim encompasses the ancient cities of Priene and Miletus, along with the temple of Didyma. The temple was linked to Miletus, and Herodotus refers to it under the name of the family of priests, the Branchidae. I first visited Priene, Didyma, and Miletus in , when teaching at the Nesin Mathematics Village in Şirince, Selçuk, İzmir. The district of Selçuk contains also the ruins of Eph- esus, home town of Heraclitus. In , I drafted my Miletus talk in the Math Village. Since then, I have edited and added to these notes. -

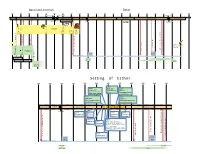

Setting of Esther

Daniel and Jeremiah Esther 610 600 590 580 570 560 550 540 530 520 510 500 490 480 470 460 450 440 430 420 410 400 Amel-marduk 561-560 Labashi-marduk 556 Xerxes II 425-424 Cambyses Nabopolassar Nebuchadnezzar 605-562 Nabonidus 556-536 Cyrus 539-530 Darius I 521-486 Xerxes I 486-465 Artaxerxes I 465-424 Darius II 423-404 625-605 529-522 Nergal-shal-usur 559-557 Belshazzar 553-539 Smerdis 522 ESTHER Sogdianus 424-423 DANIEL 12 - 8 - Dan 3 Dan Dan 2 Dan 4 Dan 7 Dan 6, 9 5, Dan 10 Dan The The statue dream, 604 Fiery furnace, c603 The tree dream, c571 Vision of four beasts, 553 Vision of ram &goat, 551 Fall of Babylon, 539 Lion’s den Reading of Jeremiah, 539 Vision of the end, 536 , 538 , Deportation, Deportation, 605 st 1 Deportation, 597 Deportation, Deportation, 587 Deportation, Sheshbazzar nd rd Letters sent from Jews at 2 3 Elephantine to Yohanan, high priest in Jerusalem, 410 and 407 Nehemiah returned to Artaxerxes, Artaxerxes, 433 Nehemiah toreturned visit of Nehemiah, Nehemiah, 432 visit of visit of Nehemiah, 445 visitof Nehemiah, return, return, led by st nd Return of Ezra, 458 of Return Ezra, 1 2 st JEREMIAH 1 Walls of 29 25 Temple Jerusalem rebuilt Jer Jer Message Message to exiles, 597 Prophecy Prophecy of captivity, 605 rebuilt, Temple foundation laid 520-516 443 Jehoiakim 609-598 HAGGAI NEHEMIAH Jehoiachin 608-597 Zedekiah 597-587 flight585 to Forced Egypt, ZECHARIAH EZRA MALACHI 44 Jer Prophecy Prophecy against refugees in Egypt Setting of Esther 540 530 520 510 500 490 480 470 460 450 440 430 478 BC 482 BC Esther 2:16 474 -

WRATH of ACHILLES: the MYTHS of the TROJAN WAR “The Feast of Peleus”

SING, GODDESS OF THE WRATH OF ACHILLES: THE MYTHS OF THE TROJAN WAR “The Feast Of Peleus” E. Burne-Jones (1872-81) Eris The Greek Goddess of Chaos Paris and the nymph Oinone happy on Mt. Ida Peter Paul Rubens, “Judgment Of Paris” Salvador Dali, “The Judgment of Paris” (1960-64) “Paris and Helen,” Jacques-Louis David (1788) “The Abduction of Helen” From an illuminated edition of Ovid’s Metamorphosis (late 15th c.) OATH OF TYNDAREUS When Helen reached marriageable age, the greatest kings and warriors from all Greece sought to win her hand. They brought magnificent gifts to her mortal father Tyndareus. The suitors included Ajax, Peleus, Diomedes, Patroclus and Odysseus. In return for Tyndareus’ niece Penelope in marriage, Odysseus drew up an oath to be taken by all the suitors. They would swear to accept the choice of Tyndareus. If any man ever took Helen by force, they would fight to regain her for her lawful husband. Tyndareus selected Menelaus, king of Sparta, who had brought the most valuable gifts. “Odysseus’ Induction,” Heywood Hardy (1874) “Thetis Dips Achilles Into The River Syx” Antoine Borel (18th c.) Achilles taught to play the lyre by Chiron Jan de Bray, “The Discovery of Achilles Among the Daughters of Lycomedes” [1664] Aulis today Achilles wounds Telephus in Mysia Iphigenia, Achilles, Clytemnestra and Agamemnon at Aulis “Sacrifice of Iphigenia at Aulis,” A wall painting from the House of the Tragic Poet at Pompeii 63-70 CE Peter Pietersz Lastman, “Orestes and Pylades Disputing the Altar” (1614) Philoctetes with Heracles’ bow on Lemnos Protesilaus steps ashore at Troy Patroclus separates Briseis from Achilles Briseis and Agamemnon Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres, “Jupiter and Thetis” (1811) Paris and Menelaus in single combat Aeneas and Aphrodite were both wounded by Diomedes “Achilles Receives Agamemnon’s Messengers,” Jacques-Louis David (1801) “Helen on the Walls of Troy,” -Gustave Moreau, c.