Archaeological Work at Poggio Colla (Vicchio Di Mugello) P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

II EDIZIONE Bambini E Gli Adolescenti Come “Individui”

Con il patrocinio di La data ricorda il giorno in cui l' Assemblea Partecipano al Progetto In collaborazione con la Commizssione 7 Generale delle Nazioni Unite adottò, nel 1989, di Firenze la convenzione ONU sui diritti dell'infanzia e dell'adolescenza. In collaborazione con Con il contributo di La “Carta dei Diritti del Bambino” fu scritta già nel 1923 da Eglantyne Jebb, dama della Croce Rossa. Ancora oggi molti sono i bambini e gli adolescenti, anche in Italia, vittime di violenza, abusi, discriminazioni, che vivono situazioni di trascuratezza sociale – psicologica nonché scolastica e culturale. Tutti abbiamo il dovere di prendere coscienza dell'importanza di trattare i II EDIZIONE bambini e gli adolescenti come “individui”. Il tema Giornata Mondiale è particolarmente sentito dagli Artisti Fiesolani che operano affinché “l'Arte e la Cultura” possano dei Diritti dell'Infanzia mantenere il primato tra le attività umane. e dell'Adolescenza Artisti in esposizione: Fiamma Antoni Ciotti Irina Meniailova Mariangela Bartoloni Valerio Mirannalti Francesco Beccastrini Lorenzo Montagni Stefania Biagioni Susanna Pellegrini Istituto Comprensivo “Coverciano” Via Salvi Cristiani, 3 – 50135 Firenze Fernando Cardenas Scuola Primaria S.Maria a Coverciano Francesco Perna Barbara Cascini Puccio Pucci Alessandro Ciappi COMUNE DI GAMBASSI TERME ISTITUTO COMPRENSIVO STATALE Matteo Rimi E DI MONTAIONE “Ernesto BALDUCCI” Roberto Coccoloni Mariadonata Sirleo Andrea Sole Costa Roberto D’Angelo Sanja Spasic Laura Felici Paola Stazzoni Alessandro Goggioli Sara -

[email protected] [email protected] NUMERI UTILI / / UTILI NUMERI User Numbers User

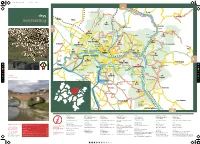

A3-Map-Pontassieve.pdf 1 03/12/19 19:24 ✟ CONVENTO ✟ PIEVE DI S. GIOVANNI MAGGIORE di Bilancino DI BOSCO AI FRATI Villore CAFAGGIOLO Borgo S. Lorenzo BOLOGNA Le Croci di Calenzano Vicchio Map S. Godenzo Pontassieve Agliana PRATO A1 Legri Vaglia CONVENTO Dicomano PISA DI MONTE SENARIO Frascole Rincine Pratolino Contea Calenzano Olmo Acone VILLA DEMIDOFF S. Brigida Cercina Londa A11 Colonnata Scopeti Capalle LA PETRAIA Caldine Sesto Fiorentino CASTELLO Monteloro Pomino Carmignano ✟ PIEVE DI S. BARTOLOMEO Campi Bisenzio AEROPORTO Fiesole Molin del Piano DI FIRENZE Careggi Stia S. Donnino Sieci Signa Pratovecchio Vinci Badia a Settimo FIRENZE Settignano Pontassieve Diacceto FI-PI-LI Castra Pelago Rosano RAVENNA Lastra a Signa Cerreto Guidi ✟ Villamagna Ponte a Cappiano Limite Scandicci Tosi Galluzzo Montemignaio Sovigliana Bagno a Ripoli S. Ellero C Capraia Ponte a Ema Fucecchio Mosciano Certosa Vallombrosa M Grassina S. Croce sull’Arno Rignano sull’Arno ✟ PIEVE Saltino Antella A PITIANA Poppi Y Ginestra Fiorentina S. Donato Empoli in Collina CM Tavarnuzze Chiesanuova Leccio MY Castelfranco di sotto Firenze e torrente Pesa S. Vincenzo a Torri CY Ponte a Elsa Impruneta Area Fiorentina Cerbaia A1 Reggello CMY FI-PI-LI S. Miniato ✟ S. Casciano in Val di Pesa FIRENZE-SIENA PIEVE DI CASCIA K S. Polo in Chianti Baccaiano Montopoli in Val d’Arno Il Ferrone Strada in Chianti Incisa Poppiano Montespertoli Mercatale in Val di Pesa Pian di Scò Cambiano Castelnuovo d’Elsa Cintoia Figline Passo dei Pecorai Palaia Dudda Greve in Chianti Loro Ciuffenna Gaville ✟ PIEVE DI Mura S. ROMOLO S. Giovanni Valdarno Tavarnelle in Val di Pesa AREZZO Terranuova Bracciolini Montaione ✟ Peccioli Certaldo S. -

Posti INFANZIA

SCUOLA DELL'INFANZIA - DISPONIBILITA' SUPPLENZE GPS A.S. 2021/22 Tipo di Posti al Posti al Ore Sede Denominazione Scuola Comune posto 31/8 30/6 Residue FIEE260008 DD Fucecchio FUCECCHIO AN 2 10 FIEE260008 DD Fucecchio FUCECCHIO EH 4 FIIC80800B IC Marradi MARRADI AN 1 FIIC80800B IC Marradi MARRADI EH 13 GAMBASSI FIIC809007 Ic Gambassi Terme AN 12 TERME GAMBASSI FIIC809007 Ic Gambassi Terme EH 2 13 TERME CAPRAIA E FIIC81000B IC Capraia e Limite AN LIMITE CAPRAIA E FIIC81000B IC Capraia e Limite EH 1 LIMITE MONTELUPO FIIC811007 IC Montelupo Fiorentino AN 1 FIORENTINO MONTELUPO FIIC811007 IC Montelupo Fiorentino EH 13 FIORENTINO FIIC812003 IC Gandhi FIRENZE AN 2 FIIC812003 IC Gandhi FIRENZE EH 2 12 FIIC81300V IC Amerigo Vespucci FIRENZE AN 1 FIIC81300V IC Amerigo Vespucci FIRENZE EH 5 13 FIIC81400P IC Dicomano DICOMANO AN FIIC81400P IC Dicomano DICOMANO EH 1 FIIC81500E IC Vicchio VICCHIO AN 1 FIIC81500E IC Vicchio VICCHIO EH 1 2 FIIC81500E IC Vicchio VICCHIO HN 1 FIIC81600A IC Firenzuola FIRENZUOLA AN 3 FIIC81600A IC Firenzuola FIRENZUOLA EH 1 1 MONTESPERTOL FIIC817006 IC Montespertoli AN I MONTESPERTOL FIIC817006 IC Montespertoli EH 1 I BARBERINO DI FIIC818002 IC Barberino Di Mugello AN 1 MUGELLO BARBERINO DI FIIC818002 IC Barberino Di Mugello EH 1 2 MUGELLO BARBERINO FIIC81900T IC Tavarnelle AN 1 TAVARNELLE BARBERINO FIIC81900T IC Tavarnelle EH 2 1 12 TAVARNELLE FIIC820002 IC Fiesole FIESOLE AN 2 FIIC820002 IC Fiesole FIESOLE EH 1 2 FIIC82100T IC Campi - Giorgio La Pira CAMPI BISENZIO AN 1 FIIC82100T IC Campi - Giorgio La Pira CAMPI BISENZIO -

Monte Loro, Monteloro

Dizionario Geografico, Fisico e Storico della Toscana (E. Repetti) http://193.205.4.99/repetti/ Monte Loro, Monteloro ID: 2472 N. scheda: 28440 Volume: 2; 3; 6S Pagina: 816; 410 - 411; 156 ______________________________________Riferimenti: Toponimo IGM: Monteloro Comune: PONTASSIEVE Provincia: FI Quadrante IGM: 106-2 Coordinate (long., lat.) Gauss Boaga: 1691012, 4854078 WGS 1984: 11.37593, 43.81665 ______________________________________ UTM (32N): 691076, 4854252 Denominazione: Monte Loro, Monteloro Popolo: S. Giovanni Battista a Monteloro Piviere: S. Giovanni Battista a Monteloro Comunità: Pontassieve Giurisdizione: Pontassieve Diocesi: Fiesole Compartimento: Firenze Stato: Granducato di Toscana ______________________________________ LORO (MONTE) Mons Laurus nel Val d'Arno fiorentino. - Pieve antica (S. Giovanni Battista) con castellare, ora Casale, dal quale prese il nome la contrada e una delle 76 leghe del contado fiorentino, nella Comunità Giurisdizione e quasi 4 miglia toscane a maestrale del Pontassieve, Diocesi di Fiesole, Compartimento di Firenze. Trovasi in un colle fra il torrente Sieci , che ne lambisce le falde a levante, e quello delle Falle che egli scorre a ponente, entrambi tributari dal lato destro del fiume Arno, che è a circa un miglio toscano e mezzo a ostro di Monte Loro. La memoria più antica, che mi sia caduta sotto gli occhi di questo Monte Loro, ritengo che sia quella di un istrumento rogato in Cercina li 24 aprile dell'anno 1042, col quale donna Waldrada del fu Roberto, moglie allora di Sigifredo figlio di Rodolfo, autorizzata dal giudice e da altri buonomini, rinunziò e figurò di vendere ai figli del secondo letto tutte le case, terre, corti e castelli che godeva nei contadi fiorentino e fiesolano, di provenienza del fu Guido suo primo consorte, fra le quali possessioni eravi una casa e corte in Monte Loro , ed altre nel vicino Monte Fano (ARCH. -

Ambito 09 Mugello

QUADRO CONOSCITIVO Ambito n°9 MUGELLO PROVINCE : Firenze TERRITORI APPARTENENTI AI COMUNI : Barberino di Mugello, Borgo San Lorenzo, Dicomano, Londa, Pelago, Rufina, San Godenzo, San Piero a Sieve, Scarperia, Vaglia, Vicchio OROGRAFIA – IDROGRAFIA Questa area è una entità geografica ben definita: la parte centrale del Mugello non è che l’alveo del lago pliocenico, di 300 kmq circa, che vi è esistito alla fine del periodo terziario. L’avvallamento, drenato dal fiume Sieve, è limitato dall’Appennino a nord, a sud dalla catena parallela all’Appennino che separa il Mugello dalla conca di Firenze e che culmina nel m. Giovi (992m.), a est dal massiccio del Falterona-M. Falco (m. 1658, al confine fra Toscana e Romagna). Alla stretta di Vicchio la Sieve, sbarrata dal massiccio del Falte- rona, piega gradualmente verso Sud, percorrendo il tratto generalmente indicato come Val di Sieve, e si versa nell’Arno (del quale è il maggior affluente) presso Pontassieve. L’area, fortemente sismica, è stata colpita da grandi terremoti nel 1542, 1672, 1919. Il paesaggio di questo ambito si presenta, pertanto, con caratteri morfologici di base molto diversificati. Dal paesaggio pedemontano dei rilievi dell’Appennino tosco-romagnolo, con gli insediamenti di Mangona, Casaglia, Petrognano, Castagno d’Andrea, Fornace, si passa a quello dei pianori del Mugello centrale, delimitati da ripide balze e costoni tufacei. Dal fondovalle del fiume Sieve, i versanti collinari di S. Cresci, Arliano e Montebonello risalgono alle arenarie di Monte Senario e alle formazioni calcaree di Monte Morello e Monte Giovi. VEGETAZIONE Il mosaico paesistico presenta un’articolazione decisamente condizionata dalla configurazione morfologica complessiva, che connota l’ambito come conca intermontana. -

Unusal Tuscany 2020.Pdf

SAN GIMIGNANO Unusual proposal around an amazing ancinet destination Taste of Tuscany Spend three days in San Gimignano, fill your eyes with art and landscapes, taste wines and typical gastronomy, but we warn you: you will like it so much that you will want to come back ... Two nights in b & b / guest house including Vernaccia tasting € 120.00 per person (breakfast included) Two nights in a farmhouse with swimming pool / hotel with swimming pool including Vernaccia tasting € 160.00 per person (breakfast included) Fun and culture in Tuscany 1st day - Saturday Arrival at the chosen accomodation and check in (any transfers from the airport and / or station on request) Leisure time In the evening you will meet one of our representatives who will explain the excursions you have already booked and everything you need to make your holiday unforgettable. And to make everything warmer, he will offer you a tasting of wine and typical products 2nd day - Sunday Leisure time 3rd day - Monday After breakfast, meet your guide for a walk through San Gimignano where we will tell you about the story, but also mysteries and legends that make this medieval city so “charmant” (about 3.5 hours) Leisure time 4th day - Tuesday Leisure time In the evening we will offer you a bio aperitif in the vineyard with a splendid view of the valley and the skyline of San Gimignano 5th day - Wednesday After breakfast meeting with our driver who will accompany you to the sea. When booking, you can choose between a full day at the reserved private and organized beach or a mini-cruise : boarding in Castiglione from 8.00 am navigation along the coasts and the splendid beaches of the Maremma Park: the guides on board will illustrate its characteristics and will be available to passengers for all information on the Tuscan Archipelago, the Maremma coasts and the Cetaceans that they often cheer our crossings. -

2.1 Il PIT – Piano Di Indirizzo Territoriale Regionale

19 2. Il Quadro di riferimento sovracomunale: piani/programmi di area vasta e gli strumenti della pianificazione sovraordinata 2.1 Il P.I.T. – Piano di Indirizzo Territoriale regionale La ricerca di una comune sinergia tra gli obiettivi, gli indirizzi e le scelte di piano degli strumenti di competenza della Regione e della Provincia e quelli locali interni al Piano Strutturale, auspicata come si è accennato sulla legislazione toscana regionale per garantire un organico e funzionale sistema di programmazione e pianificazione, ha impegnato il gruppo di lavoro fin dall’atto di avvio del procedimento sia per caratterizzare il quadro conoscitivo e le linee di sviluppo dell’area, ma soprattutto per rendere conformi i criteri e le direttive del Piano Strutturale alle prescrizioni del PIT regionale e del Piano di Coordinamento provinciale. Per quanto riguarda il PIT, (approvato con deliberazione del Consiglio Regionale n.12 del 25 Gennaio 2000) questo strumento rappresenta l’atto di programmazione con il quale la Regione Toscana in attuazione della legge urbanistica e in conformità con le indicazioni del Programma Regionale di Sviluppo, stabilisce gli orientamenti per la pianificazione degli Enti Locali e definisce gli obiettivi operativi della propria politica territoriale. Rappresenta cioè lo strumento regionale per il governo del territorio che individua e indirizza le politiche territoriali a carattere strategico che appaiono necessarie per innescare processi di miglioramento delle condizioni di sviluppo, per ricercare elementi di maggiore -

Etruscan Jewelry and Identity

Chapter 19 Etruscan Jewelry and Identity Alexis Q. Castor 1. Introduction When Etruscan jewelry is found, it is already displaced from its intended purpose. In a tomb, the typical archaeological context that yields gold, silver, ivory, or amber, the ornaments are arranged in a deliberate deposit intended for eternity. They represent neither daily nor special occasion costume, but rather are pieces selected and placed in ways that those who prepared the body, likely women, believed was significant for personal or ritual reasons. Indeed, there is no guarantee that the jewelry found on a body ever belonged to the dead. For an element of dress that the living regularly adapted to convey different looks, such permanence is entirely artificial. Today, museums house jewelry in special cases within galleries, further sep- arating the material from its original display on the body. Simply moving beyond these simu- lations requires no little effort of imagination on the part of researchers who seek to understand how Etruscans used these most personal artifacts. The approach adopted in this chapter draws on anthropological methods, especially those studies that highlight the changing self‐identity and public presentation necessary at different stages of life. As demonstrated by contemporary examples, young adults can pierce various body parts, couples exchange rings at weddings, politicians adorn their lapels with flags, and military veterans pin on medals for a parade. The wearer can add or remove all of these acces- sories depending on how he or she moves through different political, personal, economic, social, or religious settings. Cultural anthropologists who apply this theoretical framework have access to many details of life‐stage and object‐use that are lost to us. -

Profilo Di Salute

Società della Salute del Mugello Profilo di Salute Via Palmiro Togliatti, 29 - 50032 BORGO SAN LORENZO (FI) - Tel. 0558451430 – Fax 0558451414 e-mail: [email protected] Società della Salute del Mugello Profilo di Salute … … oggi e’ rivoluzionario tessere i rapporti, far vivere i territori: in altre parole, costruire società PREMESSA La Società della Salute del Mugello rappresentata dai Comuni della Zona socio sanitaria, dall’Azienda sanitaria di Firenze e dalla Comunità Montana Mugello vuole, in estrema sintesi, valorizzare il costante proporsi della comunità locale, in tutte le sue espressioni, nell’ottica della facilitazione dell’accesso, della risoluzione delle componenti burocratiche e dell’effettivo, diretto coinvolgimento della popolazione e degli operatori nella tutela della salute e del benessere sociale. Rispetto alle funzioni di governo, il Piano Integrato di Salute - e cioè un modello di programmazione per obiettivi più complessivi di salute - costituisce la modalità prioritaria di espressione della Società della Salute. Il prodotto da raggiungere con le necessarie gradualità è l’Immagine di salute della Zona, un quadro sintetico dei problemi e delle opportunità che caratterizzano le condizioni sociali, sanitarie e ambientali del territorio. E’ quindi necessario avviare il processo di programmazione con la formalizzazione del Profilo di Salute di Zona, un primo strumento che raccoglie e ordina i dati demografici, sanitari, sociali e ambientali disponibili e contiene i primi indirizzi per la predisposizione del Piano. I dati disponibili non sono ancora completi (mancano ad es. le risultanze del censimento, dati ambientali e dati epidemiologici disaggregati almeno fra i Comuni prettamente montani e gli altri) tuttavia per la storia di integrazione ormai consolidata in questo territorio molti parametri utili sono già acquisiti per cui esiste una preliminare identità di welfare di zona che ha consentito anche l’avvio della sperimentazione della SdS. -

Mugello Settembre 2020+Inv

Regione Toscana Giunta regionale Principali interventi regionali a favore del Mugello Anni 2015-2020 Barberino di Mugello Borgo San Lorenzo Dicomano Firenzuola Marradi Palazzuolo sul Senio Scarperia e San Piero Vicchio Direzione Programmazione e bilancio Settore Controllo strategico e di gestione Settembre 2020 INDICE ORDINE PUBBLICO E SICUREZZA .................................................................................................. 3 SISTEMA INTEGRATO DI SICUREZZA URBANA.....................................................................................................3 ISTRUZIONE E DIRITTO ALLO STUDIO ..........................................................................................3 TUTELA E VALORIZZAZIONE DEI BENI E DELLE ATTIVITÀ CULTURALI.......................................... 3 POLITICHE GIOVANILI, SPORT E TEMPO LIBERO..........................................................................4 SPORT E TEMPO LIBERO....................................................................................................................................4 GIOVANI...........................................................................................................................................................4 TURISMO........................................................................................................................................4 ASSETTO DEL TERRITORIO ED EDILIZIA ABITATIVA ....................................................................4 URBANISTICA E ASSETTO DEL TERRITORIO .......................................................................................................4 -

Punti Di Arrivo P U N T I D I P a R T E N

SABATO 28 (orario chiusura viabilità 10:30 - 12:30) Si precisa che nell'intervallo fra due gare successive nello stesso giorno i percorsi gara non vengono riaperti alla circolazione, oltre a questo si ricorda che gli orari di chiusura e la viabilità potranno subire variazioni per cui si consiglia di fare sempre una verifica prima di spostarsi sulle pagine web www.imobi.fi.it Come utilizzare la scacchiera e individuare il proprio percorso: Le varie zone del territorio provinciale sono disposte sia in verticale (punto di partenza) che in orizzontale (punto di arrivo); per identificare il proprio percorso occorre incrociare la riga del punto di partenza con la colonna del punto di arrivo. I percorsi sono individuati tenendo conto che tutte le strade interessate dai percorsi di gara e le limitrofe saranno chiuse. Le zono di Firenze indicate nella scacchiera sono intese come ingressi alla città, per le direttrici di Quartiere consultare la scacchiera del Comune di Firenze ( mondialiciclismo2013.comune.fi.it ) PUNTI DI ARRIVO MUGELLO VALDARNO PIANA FIORENTINA FIESOLE FIRENZE Calenzano - San Lato Scandicci - Sesto Barberino Borgo San Lato EMPOLI CHIANTI Donnino Bagno a Lastra a Fiorentino - Signa Centro Caldine Sud Galluzzo Isolotto Novoli di Mugello Lorenzo Pontassieve (Campi Ripoli Signa Campi Bisenzio) Bisenzio SP8 SP8 San Piero a A1 ingresso San Piero a SP8 A1 ingresso A1 ingresso Barberinese - Barberinese - Sieve - A1 ingresso A1 ingresso A1 ingresso Barberino di SP8 Sieve - A1 ingresso Barberinese - Barberino di Barberino di Le Croci Le -

Technical Specifications for Registration of Geographical Indications

TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS FOR REGISTRATION OF GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATIONS NAME OF GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATION Chianti PRODUCT CATEGORY Wine COUNTRY OF ORIGIN Italy APPLICANT CONSORZIO VINO CHIANTI 9 VIALE BELFIORE 50144 Firenze Italy Tel. +39. 055333600 / Fax. +39. 055333601 [email protected] PROTECTION IN COUNTRY OF ORIGIN Date of Protection in the European Union: 18/09/1973 Date of protection in the Member State and reference to national decision: 30/08/1967 - DPR 09/08/1967 published in GURI (Official Journal of the Italian Republic) n. 217 – 30/08/1967 PRODUCT DESCRIPTION Raw Material - CESANESE D'AFFILE N - Canaiolo nero n. - CABERNET SAUVIGNON N. - CABERNET FRANC N. - BARBERA N. - ANCELLOTTA N. - ALICANTE N. - ALEATICO N. - TREBBIANO TOSCANO - SANGIOVESE N. - RIESLING ITALICO B. - Sauvignon B - Colombana Nera N - Colorino N - Roussane B - Bracciola Nera N - Clairette B - Greco B - Grechetto B - Viogner B - Albarola B - Ansonica B - Foglia Tonda N - Abrusco N - Refosco dal Peduncolo Rosso N - Chardonnay B - Incrocio Bruni 54 B - Riesling Italico B - Riesling B - Fiano B - Teroldego N - Tempranillo N - Moscato Bianco B - Montepulciano N - Verdicchio Bianco B - Pinot Bianco B - Biancone B - Rebo N - Livornese Bianca B - Vermentino B - Petit Verdot N - Lambrusco Maestri N - Carignano N - Carmenere N - Bonamico N - Mazzese N - Calabrese N - Malvasia Nera di Lecce N - Malvasia Nera di Brindisi N - Malvasia N - Malvasia Istriana B - Vernaccia di S. Giminiano B - Manzoni Bianco B - Muller-Thurgau B - Pollera Nera N - Syrah N - Canina Nera N - Canaiolo Bianco B - Pinot Grigio G - Prugnolo Gentile N - Verdello B - Marsanne B - Mammolo N - Vermentino Nero N - Durella B - Malvasia Bianca di Candia B - Barsaglina N - Sémillon B - Merlot N - Malbech N - Malvasia Bianca Lunga B - Pinot Nero N - Verdea B - Caloria N - Albana B - Groppello Gentile N - Groppello di S.