Epistemic Verbal Endings and Copulas (Preview)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PPD Talk by Prof. Nicolas Tournadre

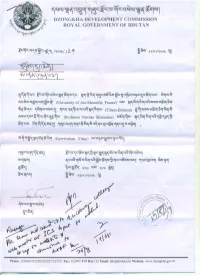

-. '" ~~Q.l·~~·q~~·~~~·~,,·rq·~,,·qt4Q.l·~~·l~~l DZONGKHA DEVELOPMENT COMMISSION ROYAL GOVERNMENT OF BHUTAN "'~=<~r\"~\"\~T"""""'" ..~ D. oN' qJ{, n..,~~V){"\ ..."."" ~ t ,. '" '" '" -.r '" 7::F. '" C\.. '" C\.. '" C\ '" '" '" ~.~~.~.u-yz:::..~z:::..(tI.~z:::..~t4QJ.~~.ct:l~~.~z:::~~·~·"~·~~z:::.·o-!sa·,,o-!·~z::r:Ir~~~·o-!~o-!·~r:;r·sa~·QJ~·.~~~.~.. ~".~QJ.~~~.QJ~.~r:;r.~. (University of Aix-Marseille, France) QJ~' ~~.~~.~~.t.lq.o-!(tI~.~~~.~~. C\..C\.. C\.. C\.. C\.. C\.. C\.. ",C\C\..C\.. ~~'~'~z:::.' ~~~~'r:;r~QJ'~' ~z:::.~·-o~·7·o-!·QJ·u-y~·~~·,,~~·(Tibeto-Bunnan) ~.~.~(tI~.~a:;~.-o~.~~.o-!. C\..-.r '" C\.. '" C\.. C\.. C\.. C\.. '" C\.. ~(tI~.~r:;rz:::..~."l.QJ.~".~~.~~.(Professor Nicolas 'J:oumadre) o-!a:;~'~~' ~~·u-y~·,,~·t.I~·~S·~~~·~· '" '" C\..'" C\..C\.. C\.. C\ '" '" sa~'QJ~' ~~.~.~~.~~.~. ~~z:::.·r:;r4~·~~z:::.·~·~~·o-!·~~·~z:::.·r~r~S~·~~z:::.·~·r:;r·o-!~~1r '" '" C\.. '" C\.. C\..-.r '" ~~z:::.·r:;r4~·~~·~~1 ~z:::..(tI.~z:::..a:;~.~~.~.~".~~.~~·o-!z:::.·o-!·u-y~·t.I~·~z:::.·~C4QJl ~'~~~1 ~z:::.'t.Iq·~'*r:;r·~~·t.lq·~r:;r·l~~·~·'1QJ·~i!~~·(tIz:::.l"l·'1:fz:::.'Sz:::.·~1a5.J·~~ ~l~l ~o-!'~l~' ~:~o QJ~' l{.:oo ~~l C\..~ a;~·:uz:::.~1 ~'a:l~' '.l...'.l...lo"I'.l...o'}~ ~l 4~·"r:;r·~QJ·o-!~~1 '" §z:::.·a:;~1 Phone: 322663/325226/325227/323721 Fax: 322992 P.O Box 122 Email: [email protected] Website: www.dzongkha.gov.bt Nicolas Tournadre's Curriculum Vitae Name: Nicolas Toumadre / '",?~.q~"'a:;~.~.q~~. Professor at the University of Aix-Marseille, linguistics department CN~~r~r"'- aI~:~llrmJ::r~ra5~'a,- ~l·~~II ""·qc:rc5~·~~ l~'ifl~"- 'a5~'aII E~ail : [email protected] Professional site: www.nicolas-tournadre.net Education 1984 MA in Russian Literature, Sorbonne University 1987 BA in Tibetan language and civilisation, Institute of Oriental Languages and Civilisation (INalco, Paris) 1989 Louis Forest prize-winning awarded by the "Chancellerie des Universites de Paris". -

Buddhism and Medicine in Tibet: Origins, Ethics, and Tradition

Buddhism and Medicine in Tibet: Origins, Ethics, and Tradition William A. McGrath Herndon, Virginia B.Sc., University of Virginia, 2007 M.A., University of Virginia, 2015 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Religious Studies University of Virginia May, 2017 Abstract This dissertation claims that the turn of the fourteenth century marks a previously unrecognized period of intellectual unification and standardization in the Tibetan medical tradition. Prior to this time, approaches to healing in Tibet were fragmented, variegated, and incommensurable—an intellectual environment in which lineages of tantric diviners and scholarly literati came to both influence and compete with the schools of clinical physicians. Careful engagement with recently published manuscripts reveals that centuries of translation, assimilation, and intellectual development culminated in the unification of these lineages in the seminal work of the Tibetan tradition, the Four Tantras, by the end of the thirteenth century. The Drangti family of physicians—having adopted the Four Tantras and its corpus of supplementary literature from the Yutok school—established a curriculum for their dissemination at Sakya monastery, redacting the Four Tantras as a scripture distinct from the Eighteen Partial Branches addenda. Primarily focusing on the literary contributions made by the Drangti family at the Sakya Medical House, the present dissertation demonstrates the process -

Towards a New Approach to Evidentiality : Issues and Directions for Research

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Towards a new approach to evidentiality : issues and directions for research Tournadre, Nicolas; LaPolla, Randy J. 2014 Tournadre, N., & LaPolla, R. J. (2014). Towards a new approach to evidentiality : issues and directions for research. Linguistics of the Tibeto‑Burman Area, 37(2), 240–263. doi:10.1075/ltba.37.2.04tou https://hdl.handle.net/10356/145731 https://doi.org/10.1075/ltba.37.2.04tou © 2014 John Benjamins Publishing Company. All rights reserved. This paper was published in Linguistics of the Tibeto‑Burman Area and is made available with permission of John Benjamins Publishing Company. Downloaded on 28 Sep 2021 09:48:05 SGT TOWARDS A NEW APPROACH TO EVIDENTIALITY: ISSUES AND DIRECTIONS FOR RESEARCH Nicolas Tournadre Randy J. LaPolla University of Aix-Marseille Nanyang Technological University and Lacito (CNRS) 0. INTRODUCTION Evidentiality is often defined as the grammatical means of expressing information source (e.g. Aikhenvald 2004: xi, 1). In a way every language has lexical and/or grammatical means to mark evidentiality, however only about one quarter of the world’s languages have obligatory marking of evidentiality, and the geographic distribution is uneven: complex systems for marking evidentiality are found among Tibeto-Burman, North American, South American, and Caucasian languages, and less complex systems are found in Austronesian, Slavic, Turkic, Indo-Iranian, Australian, and Finno-Ugrian languages, but evidential marking is almost completely absent from Africa. There is already a body of literature including in-depth descriptions of individual systems and some typological surveys (for the latter see Chafe and Nichols 1986; Guentchéva 1996; LTBA 24(1) Special Issue on Person and Evidence in Himalayan Languages; Aikhenvald 2004, 2011; Aikhenvald & LaPolla 2007 and the papers in that special issue (30(2)) of LTBA on evidentials); Guentchéva & Landaburu 2007). -

Evidential Systems of Tibetan Languages Trends in Linguistics Studies and Monographs

Lauren Gawne, Nathan W. Hill (Eds.) Evidential Systems of Tibetan Languages Trends in Linguistics Studies and Monographs Editor Volker Gast Editorial Board Walter Bisang Jan Terje Faarlund Hans Henrich Hock Natalia Levshina Heiko Narrog Matthias Schlesewsky Amir Zeldes Niina Ning Zhang Editor responsible for this volume Walter Bisang and Volker Gast Volume 302 Evidential Systems of Tibetan Languages Edited by Lauren Gawne Nathan W. Hill ISBN 978-3-11-046018-6 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-047374-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-047187-8 ISSN 1861-4302 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the internet http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Typesetting: Compuscript Ltd., Shannon, Ireland Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Contents Nathan W. Hill and Lauren Gawne 1 The contribution of Tibetan languages to the study of evidentiality 1 Typology and history Shiho Ebihara 2 Evidentiality of the Tibetan verb snang 41 Lauren Gawne 3 Egophoric evidentiality in Bodish languages 61 Nicolas Tournadre 4 A typological sketch of evidential/epistemic categories in the Tibetic languages 95 Nathan W. Hill 5 Perfect experiential constructions: the inferential semantics of direct evidence 131 Guillaume Oisel 6 On the origin of the Lhasa Tibetan evidentials song and byung 161 Lhasa and Diasporic Tibetan Yasutoshi Yukawa 7 Lhasa Tibetan predicates 187 Nancy J. -

Tibet's Minority Languages-Diversity and Endangerment-Appendix 9 28 Sept Version

Tibet’s minority languages: Diversity and endangerment Short title: Tibet’s minority languages Authors: GERALD ROCHE (Asia Institute, University of Melbourne, [email protected])* HIROYUKI SUZUKI (IKOS, University of Oslo, [email protected]) Abstract Asia is the world’s most linguistically diverse continent, and its diversity largely conforms to established global patterns that correlate linguistic diversity with biodiversity, latitude, and topography. However, one Asian region stands out as an anomaly in these patterns—Tibet, which is often portrayed as linguistically homogenous. A growing body of research now suggests that Tibet is linguistically diverse. In this article, we examine this literature in an attempt to quantify Tibet’s linguistic diversity. We focus on the minority languages of Tibet—languages that are neither Chinese nor Tibetan. We provide five different estimates of how many minority languages are spoken in Tibet. We also interrogate these sources for clues about language endangerment among Tibet’s minority languages, and propose a sociolinguistic categorization of Tibet’s minority languages that enables broad patterns of language endangerment to be perceived. Appendices include lists of the languages identified in each of our five estimates, along with references to key sources on each language. Our survey found that as many as 60 minority languages may be spoken in Tibet, and that the majority of these languages are endangered to some degree. We hope out contribution inspires further research into the predicament of Tibet’s minority languages, and helps support community efforts to maintain and revitalize these languages. NB: This is the accepted version of this article, which was published in Modern Asian Studies in April 2018. -

Review of Nominalization in Asian Languages

Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area Volume 36.1 — April 2013 REVIEW OF NOMINALIZATION IN ASIAN LANGUAGES: DIACHRONIC AND TYPOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVES, BY FOONG HA YAP, KAREN GRUNOW-HÅRSTA AND JANICK WRONA (EDS) AMSTERDAM AND PHILADELPHIA:JOHN BENJAMINS, 2011 [Hardcover 796 pages + xvii front matter. ISBN: 978-90-272-0677-0] Nicolas Tournadre Lacito (CNRS) and Aix-Marseille University Nominalization in Asian Languages: diachronic and typological perspectives, edited by Foong Ha Yap, Karen Grunow-Hårsta & Janick Wrona (John Benjamins, 2011) has 796 pages and consists of a preface, a general introduction to the notion of nominalization in a cross-linguistic and diachronic perspective, twenty-five contributions on nominalization organized along areal and genetic lines (divided into six parts), a general index of linguistic terms, and an index of languages. The discussion on nominalization mainly deals with about sixty Asian languages belonging to two major stocks: Sino-Tibetan and Austronesian. However, the scope of this study is wider and includes Iranian languages (Indo- European), Korean, and Japanese, as well as one Papuan language (Abui). One can note that, in contradiction to the title of the book, a few important Asian families are not documented, such as Dravidian, Indic, Turkic, Mongolic, Austro- Asiatic, Miao-Yao and Tai-Kadai. Most of the contributions deal only with one language, but some deal with small groups of languages or families, such as Noonan‘s paper on Tamangic, Sze-Wing Tang‘s paper on two Sinitic languages, and Genetti‘s paper on various Tibeto-Burman languages. Some contributions have a diachronic scope (e.g. F.-H. Yap & J. -

Himalayan Linguistics Re-Evaluation of the Evidential System of Lhasa

Himalayan Linguistics, Vol. 16(2). © Himalayan Linguistics 2017 ISSN 1544-7502 Himalayan Linguistics Re-evaluation of the Evidential system of Lhasa Tibetan and its atypical functions Guillaume Oisel CNRS - LACITO ABSTRACT This paper presents a re-evaluation of the Lhasa Tibetan Evidentials and focuses on its atypical functions with control verbs. I present the use of the intentional egophoric with non-SAPs and control verbs when the speaker refers to personal knowledge and I discuss some of its restrictions. Then, I present the atypical uses of the sensorial, factual and inferential evidentials. Some of these functions have been previously noted by Agha (1993), Tournadre (1994, 1996, 2003), Denwood (1999), Garrett (2001), Vokurková (2008) and DeLancey (1985, 1997, 2001). Based on Tournadre’s analysis (2003), in which he explains the correlation between the egophoric and intentionality, I show in this paper that when the degree of intentionality is either not involved (but not unintentional) or is only partly involved, the sensorial, factual and inferential can be used with the SAP and control verbs. I also present the notion of intentionality out of focus and lower intentionality to describe these two cases. Then, I treat ‘intentionality out of focus’ in greater detail, showing that one can distinguish five different ways of reducing the focus on intentionality. KEYWORDS Evidentiality, intentionality This is a contribution from Himalayan Linguistics, Vol. 16(2): 90-128 ISSN 1544-7502 © 2017. All rights reserved. This Portable Document Format (PDF) file may not be altered in any way. Tables of contents, abstracts, and submission guidelines are available at escholarship.org/uc/himalayanlinguistics Himalayan Linguistics, Vol. -

UC Santa Barbara Himalayan Linguistics

UC Santa Barbara Himalayan Linguistics Title Outline of Chocha-Ngacha Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/76g8736c Journal Himalayan Linguistics, 14(2) Authors Tournadre, Nicolas Laurent Rigzin, Karma Publication Date 2015 DOI 10.5070/H914225395 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Himalayan Linguistics Outlines of Chocha-ngachakha An undocumented language of Bhutan related to Dzongkha Nicolas Tournadre Aix-Marseille University and Lacito (CNRS) Karma Rigzin Royal University of Bhutan ABSTRACT This paper is the first attempt to provide the outlines of the Chocha-ngachakha, a Tibetic language spoken in Eastern Bhutan. This language (particularly the Tsamang dialect described here) has preserved many archaic features that are not found in the southern Himalayas. The linguistic conservatism of Tsamang Chocha-ngachakha is not confined to phonology but extends to grammar and vocabulary. The data from Chocha-ngachakha sheds new light on the evolution of the Tibetic family. KEYWORDS Tibetic languages, languages of Bhutan, classification of the Tibetic family, descriptive linguistics, dialectology This is a contribution from Himalayan Linguistics, Vol. 14(2): 49–87. ISSN 1544-7502 © 2015. All rights reserved. This Portable Document Format (PDF) file may not be altered in any way. Tables of contents, abstracts, and submission guidelines are available at http://escholarship.org/uc/himalayanlinguistics Himalayan Linguistics, Vol. 14(2). © Himalayan Linguistics 2015 ISSN 1544-7502 Outlines of Chocha-ngachakha An undocumented language of Bhutan related to Dzongkha Nicolas Tournadre Aix-Marseille University and Lacito (CNRS) Karma Rigzin Royal University of Bhutan 1 Introduction Among the eighteen Tibeto-Burman languages (henceforth TB) found in Bhutan, seven belong to the Tibetic group or “Gangjong Bhoti” (གངས་ོངས་བྷོ་ཊིའི་ད་རིགས་ཀྱི་ཚགས་པ་)1, which was earlier called “Central Bodish” (see Tournadre, 2014). -

Linguistic Watersheds: a Model for Understanding Variation Among the Tibetic Languages

Citation Brad CHAMBERLAIN. 2015. Linguistic Watersheds: a Model for Understanding Variation among the Tibetic Languages. Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society 8:71-96 URL http://hdl.handle.net/1885/95120 Reviewed Received 29 Aug. 2015, revised text accepted 26 Nov. 2015, published December 2015 Editors Editor-In-Chief Dr Mark Alves | Managing Eds. Dr Peter Jenks, Dr Sigrid Lew, Dr Paul Sidwell Web http://jseals.org ISSN 1836-6821 www.jseals.org | Volume 8 | 2015 | Asia-Pacific Linguistics, ANU Copyright vested in the author; Creative Commons Attribution License LINGUISTIC WATERSHEDS: A MODEL FOR UNDERSTANDING VARIATION AMONG THE TIBETIC LANGUAGES Brad Chamberlain Payap University <[email protected]> Abstract This study applies the observation of alignment between geographical watersheds and linguistic groupings to the Tibetan Plateau and the Himalayas. Tournadre (2014) estimates 220 Tibetic language varieties in 25 major groupings, sharing a common linguistic ancestry. Typological groupings can be readily identified through mapping human settlements to watersheds. For areas that have yet to be researched, consistent hypotheses for typological groupings can be arrived at. Next to explaining anomalous data within a particular area or how certain linguistic features spread, a watershed-based map identifies possible linguistic areas to be researched. The concept is applied in detail to the watersheds and languages of Bhutan and then expanded out to the broader Tibetan region. Keywords: Bodish, watersheds, variation ISO 639-3 codes: adx, bod, bro, cgk, dka, dzl, dzo, goe, jul, kgy, khg, kjz, kkf, lep, lhm, lhp, lkh, luk, neh, npb, ole, scp, sgt, tgf, tsj, twm, xkf, xkz 1 Introduction The people of the Tibetan Plateau and surrounding mountains speak numerous related language varieties. -

Himalayan Linguistics Outlines of Chocha-Ngachakha an Undocumented Language of Bhutan Related to Dzongkha

Himalayan Linguistics Outlines of Chocha-ngachakha An undocumented language of Bhutan related to Dzongkha Nicolas Tournadre Aix-Marseille University and Lacito (CNRS) Karma Rigzin Royal University of Bhutan ABSTRACT This paper is the first attempt to provide the outlines of the Chocha-ngachakha, a Tibetic language spoken in Eastern Bhutan. This language (particularly the Tsamang dialect described here) has preserved many archaic features that are not found in the southern Himalayas. The linguistic conservatism of Tsamang Chocha-ngachakha is not confined to phonology but extends to grammar and vocabulary. The data from Chocha-ngachakha sheds new light on the evolution of the Tibetic family. KEYWORDS Tibetic languages, languages of Bhutan, classification of the Tibetic family, descriptive linguistics, dialectology This is a contribution from Himalayan Linguistics, Vol. 14(2): 49–87. ISSN 1544-7502 © 2015. All rights reserved. This Portable Document Format (PDF) file may not be altered in any way. Tables of contents, abstracts, and submission guidelines are available at http://escholarship.org/uc/himalayanlinguistics Himalayan Linguistics, Vol. 14(2). © Himalayan Linguistics 2015 ISSN 1544-7502 Outlines of Chocha-ngachakha An undocumented language of Bhutan related to Dzongkha Nicolas Tournadre Aix-Marseille University and Lacito (CNRS) Karma Rigzin Royal University of Bhutan 1 Introduction Among the eighteen Tibeto-Burman languages (henceforth TB) found in Bhutan, seven belong to the Tibetic group or “Gangjong Bhoti” (གངས་ོངས་བྷོ་ཊིའི་ད་རིགས་ཀྱི་ཚགས་པ་)1, which was earlier called “Central Bodish” (see Tournadre, 2014). These languages include Dzongkha ོང་ཁ་, Chocha- ngachakha ཁྱོ་ཅ་ང་ཅ་ཁ་, Lakha2 ལ་ཁ་, and Merak-Saktengkha3 མེ་རག་སག་ེང་ཁ་, Layakha 4 ལ་ཡ་ཁ, Durkha 5 ར་ཁ་ and Trashigang Kham བཀྲ་ཤིས་ང་ཁམས་ད་. -

Epistemic Modalities in Spoken Standard Tibetan

UNIVERSITE CHARLES UNIVERSITE PARIS 8 Faculté philosophique Cognition, Langage, Interaction THESE DE DOCTORAT - COTUTELLE Sciences du langage Linguistique Générale Zuzana VOKURKOVÁ EPISTEMIC MODALITIES IN SPOKEN STANDARD TIBETAN Thèse dirigée par M. Bohumil PALEK / M. Nicolas TOURNADRE Soutenue le 24 septembre 2008 Jury : Monsieur Jiří NEKVAPIL, Université Charles Monsieur Bohumil PALEK, Université Charles Monsieur Johan van der AUWERA, Université d’Anvers Monsieur Nicolas TOURNADRE, Université de Provence Madame Zlatka GUENTCHEVA, CNRS - LACITO Madame Lélia PICABIA, Professeur Emérite, Université Paris 8 2 Acknowledgements First of all, I would like to express thanks to my Ph.D. supervisors, Mr Bohumil Palek from Charles University, Prague, Czech republic, and Mr Nicolas Tournadre from the University of Paris 8, France (until 2007, currently Professor at the University of Provence), for their valuable help with my dissertation, their guidance, encouragement and commentaries. I am also grateful to Mr Tournadre for giving me the idea to study this part of the Tibetan grammar. Furthermore, I thank my Tibetan teachers and informants: Mr Dawa (teacher at Tibet University, Lhasa), Mrs Tsheyang (teacher at Tibet University, Lhasa), Mr Tanpa Gyaltsen (PICC insurance company, Lhasa), Mrs Soyag (teacher at Tibet University, Lhasa), Mr Sangda Dorje (Professor at Tibet University, Lhasa), Mr Ngawang Dakpa (teacher at Inalco, Paris), Mr Tenzin Samphel (teacher at Inalco, Paris), Mr Dorje Tsering Jiangbu (teacher at Inalco, Paris), Mr Tenzin Jigme (teacher at Charles University, Prague), Mr Thubten Kunga (teacher at Warsaw University), Mrs Pema Yonden (teacher, Dharamsala, India), and many others. Moreover, I would like to thank Mrs Lélia Picabia for accepting to be my first Ph.D. -

Tibetan Elementary Syllabus SASLI 2019

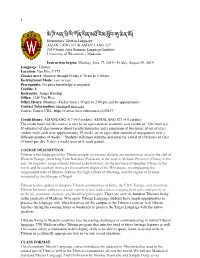

1 མེ་ཌི་སན་ཝི་སི་ཀོན་སིན་མཐ་རམ་sོབ་g་ཆེན་མོ། Elementary Tibetan Language ASIAN LANG 317 & ASIAN LANG 327 2019 South Asia Summer Language Institute University of Wisconsin – Madison Instruction begins: Monday, June 17, 2019 – Friday, August 09, 2019 Language: Tibetan Location: Van Hise # 375 Classes meet: Monday through Friday 8.30 am to 1:00 pm Instructional Mode: face to face Prerequisite: No prior knowledge is required. Credits: 8 Instructor: Jampa Khedup Office: 1248 Van Hise Office Hours: Monday –Friday from 1:00 pm to 2:00 pm and by appointments Contact Information: [email protected] Canvas Course URL: https://canvas.wisc.edu/courses/152457 Credit Hours: ASIANLANG 317 (4.0 credits), ASIANLANG 327 (4.0 credits) The credit hours for this course is met by an equivalent of academic year credits of “One hour (i.e. 50 minutes) of classroom or direct faculty/instructor and a minimum of two hours of out of class student work each over approximately 15 weeks, or an equivalent amount of engagement over a different number of weeks.” Students will meet with the instructor for a total of 156 hours of class (4 hours per day, 5 days a week) over an 8-week period. COURSE DESCRIPTION: Tibetan is the language of the Tibetan people: its various dialects are spoken over an area the size of Western Europe, stretching from Baltistan (Pakistan) in the west to Sichuan Province (China) in the east. Its linguistic range extends beyond Lake Kokonor (in the province of Qinghai, China) to the north, and its southern limits are the southern slopes of the Himalayas, encompassing the independent state of Bhutan, Sikkim, the high valleys of Mustang, and the region of Everest inhabited by the Sherpas of Nepal.