Arguments Against the Concept of 'Conjunct'/'Disjunct' in Tibetan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

7=SINO-INDIAN Phylosector

7= SINO-INDIAN phylosector Observatoire Linguistique Linguasphere Observatory page 525 7=SINO-INDIAN phylosector édition princeps foundation edition DU RÉPERTOIRE DE LA LINGUASPHÈRE 1999-2000 THE LINGUASPHERE REGISTER 1999-2000 publiée en ligne et mise à jour dès novembre 2012 published online & updated from November 2012 This phylosector comprises 22 sets of languages spoken by communities in eastern Asia, from the Himalayas to Manchuria (Heilongjiang), constituting the Sino-Tibetan (or Sino-Indian) continental affinity. See note on nomenclature below. 70= TIBETIC phylozone 71= HIMALAYIC phylozone 72= GARIC phylozone 73= KUKIC phylozone 74= MIRIC phylozone 75= KACHINIC phylozone 76= RUNGIC phylozone 77= IRRAWADDIC phylozone 78= KARENIC phylozone 79= SINITIC phylozone This continental affinity is composed of two major parts: the disparate Tibeto-Burman affinity (zones 70= to 77=), spoken by relatively small communities (with the exception of 77=) in the Himalayas and adjacent regions; and the closely related Chinese languages of the Sinitic set and net (zone 79=), spoken in eastern Asia. The Karen languages of zone 78=, formerly considered part of the Tibeto-Burman grouping, are probably best regarded as a third component of Sino-Tibetan affinity. Zone 79=Sinitic includes the outer-language with the largest number of primary voices in the world, representing the most populous network of contiguous speech-communities at the end of the 20th century ("Mainstream Chinese" or so- called 'Mandarin', standardised under the name of Putonghua). This phylosector is named 7=Sino-Indian (rather than Sino-Tibetan) to maintain the broad geographic nomenclature of all ten sectors of the linguasphere, composed of the names of continental or sub-continental entities. -

PPD Talk by Prof. Nicolas Tournadre

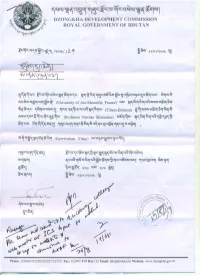

-. '" ~~Q.l·~~·q~~·~~~·~,,·rq·~,,·qt4Q.l·~~·l~~l DZONGKHA DEVELOPMENT COMMISSION ROYAL GOVERNMENT OF BHUTAN "'~=<~r\"~\"\~T"""""'" ..~ D. oN' qJ{, n..,~~V){"\ ..."."" ~ t ,. '" '" '" -.r '" 7::F. '" C\.. '" C\.. '" C\ '" '" '" ~.~~.~.u-yz:::..~z:::..(tI.~z:::..~t4QJ.~~.ct:l~~.~z:::~~·~·"~·~~z:::.·o-!sa·,,o-!·~z::r:Ir~~~·o-!~o-!·~r:;r·sa~·QJ~·.~~~.~.. ~".~QJ.~~~.QJ~.~r:;r.~. (University of Aix-Marseille, France) QJ~' ~~.~~.~~.t.lq.o-!(tI~.~~~.~~. C\..C\.. C\.. C\.. C\.. C\.. C\.. ",C\C\..C\.. ~~'~'~z:::.' ~~~~'r:;r~QJ'~' ~z:::.~·-o~·7·o-!·QJ·u-y~·~~·,,~~·(Tibeto-Bunnan) ~.~.~(tI~.~a:;~.-o~.~~.o-!. C\..-.r '" C\.. '" C\.. C\.. C\.. C\.. '" C\.. ~(tI~.~r:;rz:::..~."l.QJ.~".~~.~~.(Professor Nicolas 'J:oumadre) o-!a:;~'~~' ~~·u-y~·,,~·t.I~·~S·~~~·~· '" '" C\..'" C\..C\.. C\.. C\ '" '" sa~'QJ~' ~~.~.~~.~~.~. ~~z:::.·r:;r4~·~~z:::.·~·~~·o-!·~~·~z:::.·r~r~S~·~~z:::.·~·r:;r·o-!~~1r '" '" C\.. '" C\.. C\..-.r '" ~~z:::.·r:;r4~·~~·~~1 ~z:::..(tI.~z:::..a:;~.~~.~.~".~~.~~·o-!z:::.·o-!·u-y~·t.I~·~z:::.·~C4QJl ~'~~~1 ~z:::.'t.Iq·~'*r:;r·~~·t.lq·~r:;r·l~~·~·'1QJ·~i!~~·(tIz:::.l"l·'1:fz:::.'Sz:::.·~1a5.J·~~ ~l~l ~o-!'~l~' ~:~o QJ~' l{.:oo ~~l C\..~ a;~·:uz:::.~1 ~'a:l~' '.l...'.l...lo"I'.l...o'}~ ~l 4~·"r:;r·~QJ·o-!~~1 '" §z:::.·a:;~1 Phone: 322663/325226/325227/323721 Fax: 322992 P.O Box 122 Email: [email protected] Website: www.dzongkha.gov.bt Nicolas Tournadre's Curriculum Vitae Name: Nicolas Toumadre / '",?~.q~"'a:;~.~.q~~. Professor at the University of Aix-Marseille, linguistics department CN~~r~r"'- aI~:~llrmJ::r~ra5~'a,- ~l·~~II ""·qc:rc5~·~~ l~'ifl~"- 'a5~'aII E~ail : [email protected] Professional site: www.nicolas-tournadre.net Education 1984 MA in Russian Literature, Sorbonne University 1987 BA in Tibetan language and civilisation, Institute of Oriental Languages and Civilisation (INalco, Paris) 1989 Louis Forest prize-winning awarded by the "Chancellerie des Universites de Paris". -

ICLDC Handout

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarSpace at University of Hawai'i at Manoa 3rd ICLDC March 2nd, 2013 The impact of dialectal variation on documentation and conservation work: The view from Amdo Tibetan Zoe Tribur University of Oregon Summary For researchers interested in exploring questions of typology and linguistic universals, documentation of dialects provides priceless data, but such problems as what features constitute a dialect and who speaks it complicate the task of identifying and collecting data, especially for dialects that are low prestige or are only spoken by diglossic speakers. The field researcher must be alert to the possible existence of such forms and be aware of the issues associated with them. For the conservationist, the linguist’s instinct is to argue that dialects should be preserved as part of the community’s heritage, as well as having value in their own right, but individuals struggling to reverse language shift may feel that the reduction of diversity is a necessary step toward ensuring the survival of the language for future generations. However, the selection of a “standard” form can be problematic, sometimes resulting in conflict within the community or, more seriously, causing some speakers to be excluded from conservation efforts altogether. It behooves the field linguist to be aware of community attitudes toward diversity and to try to understand how diversity impacts language use within the community. Two varieties of Amdo Tibetan: Gro.Tshang and mGo.Log Spoken by an estimated 1.5 million people, Amdo Tibetan does not fit the profile of a typical endangered language. -

Buddhism and Medicine in Tibet: Origins, Ethics, and Tradition

Buddhism and Medicine in Tibet: Origins, Ethics, and Tradition William A. McGrath Herndon, Virginia B.Sc., University of Virginia, 2007 M.A., University of Virginia, 2015 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Religious Studies University of Virginia May, 2017 Abstract This dissertation claims that the turn of the fourteenth century marks a previously unrecognized period of intellectual unification and standardization in the Tibetan medical tradition. Prior to this time, approaches to healing in Tibet were fragmented, variegated, and incommensurable—an intellectual environment in which lineages of tantric diviners and scholarly literati came to both influence and compete with the schools of clinical physicians. Careful engagement with recently published manuscripts reveals that centuries of translation, assimilation, and intellectual development culminated in the unification of these lineages in the seminal work of the Tibetan tradition, the Four Tantras, by the end of the thirteenth century. The Drangti family of physicians—having adopted the Four Tantras and its corpus of supplementary literature from the Yutok school—established a curriculum for their dissemination at Sakya monastery, redacting the Four Tantras as a scripture distinct from the Eighteen Partial Branches addenda. Primarily focusing on the literary contributions made by the Drangti family at the Sakya Medical House, the present dissertation demonstrates the process -

Map by Steve Huffman Data from World Language Mapping System 16

Tajiki Tajiki Tajiki Shughni Southern Pashto Shughni Tajiki Wakhi Wakhi Wakhi Mandarin Chinese Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Wakhi Domaaki Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Khowar Khowar Khowar Kati Yidgha Eastern Farsi Munji Kalasha Kati KatiKati Phalura Kalami Indus Kohistani Shina Kati Prasuni Kamviri Dameli Kalami Languages of the Gawar-Bati To rw al i Chilisso Waigali Gawar-Bati Ushojo Kohistani Shina Balti Parachi Ashkun Tregami Gowro Northwest Pashayi Southwest Pashayi Grangali Bateri Ladakhi Northeast Pashayi Southeast Pashayi Shina Purik Shina Brokskat Aimaq Parya Northern Hindko Kashmiri Northern Pashto Purik Hazaragi Ladakhi Indian Subcontinent Changthang Ormuri Gujari Kashmiri Pahari-Potwari Gujari Bhadrawahi Zangskari Southern Hindko Kashmiri Ladakhi Pangwali Churahi Dogri Pattani Gahri Ormuri Chambeali Tinani Bhattiyali Gaddi Kanashi Tinani Southern Pashto Ladakhi Central Pashto Khams Tibetan Kullu Pahari KinnauriBhoti Kinnauri Sunam Majhi Western Panjabi Mandeali Jangshung Tukpa Bilaspuri Chitkuli Kinnauri Mahasu Pahari Eastern Panjabi Panang Jaunsari Western Balochi Southern Pashto Garhwali Khetrani Hazaragi Humla Rawat Central Tibetan Waneci Rawat Brahui Seraiki DarmiyaByangsi ChaudangsiDarmiya Western Balochi Kumaoni Chaudangsi Mugom Dehwari Bagri Nepali Dolpo Haryanvi Jumli Urdu Buksa Lowa Raute Eastern Balochi Tichurong Seke Sholaga Kaike Raji Rana Tharu Sonha Nar Phu ChantyalThakali Seraiki Raji Western Parbate Kham Manangba Tibetan Kathoriya Tharu Tibetan Eastern Parbate Kham Nubri Marwari Ts um Gamale Kham Eastern -

Epistemic Verbal Endings and Copulas (Preview)

Epistemic Modality in Standard Spoken Tibetan: Epistemic Verbal Endings and Copulas Copulas and Endings Verbal Tibetan: Epistemic Spoken in Standard Modality Epistemic This monograph deals with the grammatical expression of epistemic modalities in standard spoken Tibetan. It describes the system of various types of Epistemic Modality epistemic verbal endings and epistemic copulas frequently employed in the spoken language, as well as those that in Standard occur less frequently. These verbal endings are analyzed from the semantic, syntactic and pragmatic viewpoints, and illustrated by examples. Spoken Tibetan: Epistemic Verbal Endings and Copulas Zuzana Vokurková Zuzana Zuzana Vokurková KAROLINUM epistemic modality_mont.indd 1 29/06/2017 13:53 Epistemic modality in standard spoken tibetan: Epistemic verbal endings and copulas Zuzana Vokurková The original manuscript was peer-reviewed by Nicolas Tournadre, Associate Professor of Linguistics at the University of Paris 8, a member of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (Lacito), and Co-Director of the Tibetan language collection at the Tibetan and Himalayan Digital Library at the University of Virginia; Françoise Robin, Faculty Member, Tibetan department of L’Inalco, l’Université Sorbonne Paris Cité; and Professor Bohumil Palek, Faculty of Arts, Department of Linguistics, Charles University, Prague. Published by Charles University Karolinum Press Layout by Jan Šerých Typeset by Karolinum Press First English edition © Karolinum Press, 2017 © Zuzana Vokurková, 2017 ISBN 978-80-246-3588-0 -

Bibliography of the History and Culture of the Himalayan Region

Bibliography of the History and Culture of the Himalayan Region Volume Two Art Development Language and Linguistics Travel Accounts Bibliographies Bruce McCoy Owens Theodore Riccardi, Jr. Todd Thornton Lewis Table of Contents Volume II III. ART General Works on the Himalayan Region 6500 - 6670 Pakistan Himalayan Region 6671 - 6689 Kashmir Himalayan Region 6690 - 6798 General Works on the Indian Himalayan Region 6799 - 6832 North - West Indian Himalayan Region 6833 - 6854 (Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh) North - Ceritral and Eastern Indian Himalayan Region 6855 - 6878 (Bihar, Bengal, Assam, Nagaland, Meghalaya, Arunachal Pradesh, Sikkim) Bhutan 6879 - 6885 Nepal 6886 - 7242 Tibet 7243 - 7327 IV. DEVELOPMENT General Works on India and the Pan-Himalayan Region 7500 - 7559 Pakistan Himalayan Region 7560 - 7566 Nepal 7567 - 7745 V. LANGUAGE and LINGUISTICS General Works on the Pan-Himalayan Region 7800 - 7846 Pakistan Himalayan Region 7847 - 7885 Kashmir Himalayan Region 7886 - 7948 1 V. LANGUAGE (continued) VII. BIBLIOGRAPHIES Indian Himlayan Region VIII. KEY-WORD GLOSSARY (Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Bengal, Assam, Meghalaya, Nagaland, IX. SUPPLEMENTARY INDEX Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh) General Works 79.49 - 7972 Bhotic Languages 7973 - 7983 Indo-European Languages 7984 8005 Tibeto-Burmese Languages 8006 - 8066 Other Languages 8067 - 8082 Nepal General Works 8083 - 8117 Bhotic Languages 8118 -.8140 Indo-European. Languages 8141 - 8185 Tibeto-Burmese Languages 8186 - 8354 Other Languages 8355 - 8366 Tibet 8367 8389 Dictionaries 8390 - 8433 TRAVEL ACCOUNTS General Accounts of the Himalayan Region 8500 - 8516 Pakistan Himalayan Region 8517 - 8551 Kashmir Himalayan Region 8552 - 8582 North - West Indian Himalayan Region 8583 - 8594 North - East Indian Himalayan Region and Bhutan 8595 - 8604 Sikkim 8605 - 8613 Nepal 8614 - 8692 Tibet 8693 - 8732 3 III. -

Towards a New Approach to Evidentiality : Issues and Directions for Research

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Towards a new approach to evidentiality : issues and directions for research Tournadre, Nicolas; LaPolla, Randy J. 2014 Tournadre, N., & LaPolla, R. J. (2014). Towards a new approach to evidentiality : issues and directions for research. Linguistics of the Tibeto‑Burman Area, 37(2), 240–263. doi:10.1075/ltba.37.2.04tou https://hdl.handle.net/10356/145731 https://doi.org/10.1075/ltba.37.2.04tou © 2014 John Benjamins Publishing Company. All rights reserved. This paper was published in Linguistics of the Tibeto‑Burman Area and is made available with permission of John Benjamins Publishing Company. Downloaded on 28 Sep 2021 09:48:05 SGT TOWARDS A NEW APPROACH TO EVIDENTIALITY: ISSUES AND DIRECTIONS FOR RESEARCH Nicolas Tournadre Randy J. LaPolla University of Aix-Marseille Nanyang Technological University and Lacito (CNRS) 0. INTRODUCTION Evidentiality is often defined as the grammatical means of expressing information source (e.g. Aikhenvald 2004: xi, 1). In a way every language has lexical and/or grammatical means to mark evidentiality, however only about one quarter of the world’s languages have obligatory marking of evidentiality, and the geographic distribution is uneven: complex systems for marking evidentiality are found among Tibeto-Burman, North American, South American, and Caucasian languages, and less complex systems are found in Austronesian, Slavic, Turkic, Indo-Iranian, Australian, and Finno-Ugrian languages, but evidential marking is almost completely absent from Africa. There is already a body of literature including in-depth descriptions of individual systems and some typological surveys (for the latter see Chafe and Nichols 1986; Guentchéva 1996; LTBA 24(1) Special Issue on Person and Evidence in Himalayan Languages; Aikhenvald 2004, 2011; Aikhenvald & LaPolla 2007 and the papers in that special issue (30(2)) of LTBA on evidentials); Guentchéva & Landaburu 2007). -

Evidential Systems of Tibetan Languages Trends in Linguistics Studies and Monographs

Lauren Gawne, Nathan W. Hill (Eds.) Evidential Systems of Tibetan Languages Trends in Linguistics Studies and Monographs Editor Volker Gast Editorial Board Walter Bisang Jan Terje Faarlund Hans Henrich Hock Natalia Levshina Heiko Narrog Matthias Schlesewsky Amir Zeldes Niina Ning Zhang Editor responsible for this volume Walter Bisang and Volker Gast Volume 302 Evidential Systems of Tibetan Languages Edited by Lauren Gawne Nathan W. Hill ISBN 978-3-11-046018-6 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-047374-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-047187-8 ISSN 1861-4302 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the internet http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Typesetting: Compuscript Ltd., Shannon, Ireland Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Contents Nathan W. Hill and Lauren Gawne 1 The contribution of Tibetan languages to the study of evidentiality 1 Typology and history Shiho Ebihara 2 Evidentiality of the Tibetan verb snang 41 Lauren Gawne 3 Egophoric evidentiality in Bodish languages 61 Nicolas Tournadre 4 A typological sketch of evidential/epistemic categories in the Tibetic languages 95 Nathan W. Hill 5 Perfect experiential constructions: the inferential semantics of direct evidence 131 Guillaume Oisel 6 On the origin of the Lhasa Tibetan evidentials song and byung 161 Lhasa and Diasporic Tibetan Yasutoshi Yukawa 7 Lhasa Tibetan predicates 187 Nancy J. -

Geography, History, People and Economy of Nepal

6 - Geography, History, People and Economy of Nepal 1.1 Introduction Nepal’s history is better documented than Sikkim’s but its society is more complex and its people more diverse. A small country at the collision zone of the Indian and Central Asian tectonic plates that lift the Himalayas to the highest points on Earth, Nepal has three very different regions north to south; high mountains abutting Tibet, a central hilly area, and a plain that borders India almost at sea level. North-south valleys cut deep by mountain streams divide it east to west. Travel in any direction is very hard. It was unified two and a half centuries ago under a Hindu king but most Nepalis continued to practice their own religion and identified with their tribe. Even today more than ninety languages are in use. The borders were closed and the kings became figure heads in the mid-19th century. For the next hundred years Nepal was run by a single family that tax- farmed everyone else. Half a century later, most Nepalis still live in poverty and remain bonded to their family and ethnic group. In 2008 they voted to establish a secular democracy in a federally structured republic. The politicians elected to draft the associated new Constitution within two years failed to deliver. 1.2 Geography Sandwiched between India on three sides and China to the north Nepal occupies the central third of the Himalayas. It is roughly rectangular, about 500 miles wide and 125 miles north-south. In that short distance it ranges from just above sea level in the south to five and a half mile high mountains in the north. -

Map by Steve Huffman Data from World Language Mapping System 16

Mandarin Chinese Evenki Oroqen Tuva China Buriat Russian Southern Altai Oroqen Mongolia Buriat Oroqen Russian Evenki Russian Evenki Mongolia Buriat Kalmyk-Oirat Oroqen Kazakh China Buriat Kazakh Evenki Daur Oroqen Tuva Nanai Khakas Evenki Tuva Tuva Nanai Languages of China Mongolia Buriat Tuva Manchu Tuva Daur Nanai Russian Kazakh Kalmyk-Oirat Russian Kalmyk-Oirat Halh Mongolian Manchu Salar Korean Ta tar Kazakh Kalmyk-Oirat Northern UzbekTuva Russian Ta tar Uyghur SalarNorthern Uzbek Ta tar Northern Uzbek Northern Uzbek RussianTa tar Korean Manchu Xibe Northern Uzbek Uyghur Xibe Uyghur Uyghur Peripheral Mongolian Manchu Dungan Dungan Dungan Dungan Peripheral Mongolian Dungan Kalmyk-Oirat Manchu Russian Manchu Manchu Kyrgyz Manchu Manchu Manchu Northern Uzbek Manchu Manchu Manchu Manchu Manchu Korean Kyrgyz Northern Uzbek West Yugur Peripheral Mongolian Ainu Sarikoli West Yugur Manchu Ainu Jinyu Chinese East Yugur Ainu Kyrgyz Ta jik i Sarikoli East Yugur Sarikoli Sarikoli Northern Uzbek Wakhi Wakhi Kalmyk-Oirat Wakhi Kyrgyz Kalmyk-Oirat Wakhi Kyrgyz Ainu Tu Wakhi Wakhi Khowar Tu Wakhi Uyghur Korean Khowar Domaaki Khowar Tu Bonan Bonan Salar Dongxiang Shina Chilisso Kohistani Shina Balti Ladakhi Japanese Northern Pashto Shina Purik Shina Brokskat Amdo Tibetan Northern Hindko Kashmiri Purik Choni Ladakhi Changthang Gujari Kashmiri Pahari-Potwari Gujari Japanese Bhadrawahi Zangskari Kashmiri Baima Ladakhi Pangwali Mandarin Chinese Churahi Dogri Pattani Gahri Japanese Chambeali Tinani Bhattiyali Gaddi Kanashi Tinani Ladakhi Northern Qiang -

Tibet's Minority Languages-Diversity and Endangerment-Appendix 9 28 Sept Version

Tibet’s minority languages: Diversity and endangerment Short title: Tibet’s minority languages Authors: GERALD ROCHE (Asia Institute, University of Melbourne, [email protected])* HIROYUKI SUZUKI (IKOS, University of Oslo, [email protected]) Abstract Asia is the world’s most linguistically diverse continent, and its diversity largely conforms to established global patterns that correlate linguistic diversity with biodiversity, latitude, and topography. However, one Asian region stands out as an anomaly in these patterns—Tibet, which is often portrayed as linguistically homogenous. A growing body of research now suggests that Tibet is linguistically diverse. In this article, we examine this literature in an attempt to quantify Tibet’s linguistic diversity. We focus on the minority languages of Tibet—languages that are neither Chinese nor Tibetan. We provide five different estimates of how many minority languages are spoken in Tibet. We also interrogate these sources for clues about language endangerment among Tibet’s minority languages, and propose a sociolinguistic categorization of Tibet’s minority languages that enables broad patterns of language endangerment to be perceived. Appendices include lists of the languages identified in each of our five estimates, along with references to key sources on each language. Our survey found that as many as 60 minority languages may be spoken in Tibet, and that the majority of these languages are endangered to some degree. We hope out contribution inspires further research into the predicament of Tibet’s minority languages, and helps support community efforts to maintain and revitalize these languages. NB: This is the accepted version of this article, which was published in Modern Asian Studies in April 2018.