Review of Nominalization in Asian Languages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Language Documentation in the Aftermath of the 2015 Nepal Earthquakes: a Guide to Two Archives and a Web Exhibit

Vol. 13 (2019), pp. 618–651 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24914 Revised Version Received: 4 Nov 2019 Language documentation in the aftermath of the 2015 Nepal earthquakes: A guide to two archives and a web exhibit Kristine Hildebrandt Southern Illinois University Edwardsville Tanner Burge-Beckley Southern Illinois University Edwardsville Jacob Sebok Southern Illinois University Edwardsville We describe two institutionally related archives and an online exhibit represent- ing a set of Tibeto-Burman languages of Nepal. These archives and exhibit were built to house materials resulting from documentation of twelve Tibeto-Burman languages in the aftermath of the 2015 Nepal earthquakes. This account includes a detailed discussion of the different materials recorded, and how they were pre- pared for the collections. This account also provides a comparison of the two different types of archives, the different but complementary functions they serve, and a discussion of the role that online exhibits can play in the context of language documentation archives. 1. Introduction 1 The field of documentary linguistics has made use of a widear- ray of increasingly sophisticated computing technologies in recent years in order to archive, catalogue, and ultimately preserve vast quantities of audio, video, and text materials from endangered and vulnerable languages for future access by com- munity members and scholars alike. Notable examples of data archival reposito- ries, hosted and managed by higher educational institutions -

On Bhutanese and Tibetan Dzongs **

ON BHUTANESE AND TIBETAN DZONGS ** Ingun Bruskeland Amundsen** “Seen from without, it´s a rocky escarpment! Seen from within, it´s all gold and treasure!”1 There used to be impressive dzong complexes in Tibet and areas of the Himalayas with Tibetan influence. Today most of them are lost or in ruins, a few are restored as museums, and it is only in Bhutan that we find the dzongs still alive today as administration centers and monasteries. This paper reviews some of what is known about the historical developments of the dzong type of buildings in Tibet and Bhutan, and I shall thus discuss towers, khars (mkhar) and dzongs (rdzong). The first two are included in this context as they are important in the broad picture of understanding the historical background and typological developments of the later dzongs. The etymological background for the term dzong is also to be elaborated. Backdrop What we call dzongs today have a long history of development through centuries of varying religious and socio-economic conditions. Bhutanese and Tibetan histories describe periods verging on civil and religious war while others were more peaceful. The living conditions were tough, even in peaceful times. Whatever wealth one possessed had to be very well protected, whether one was a layman or a lama, since warfare and strife appear to have been endemic. Security measures * Paper presented at the workshop "The Lhasa valley: History, Conservation and Modernisation of Tibetan Architecture" at CNRS in Paris Nov. 1997, and submitted for publication in 1999. ** Ingun B. Amundsen, architect MNAL, lived and worked in Bhutan from 1987 until 1998. -

An Internal Reconstruction of Tibetan Stem Alternations1

Transactions of the Philological Society Volume 110:2 (2012) 212–224 AN INTERNAL RECONSTRUCTION OF TIBETAN STEM ALTERNATIONS1 By GUILLAUME JACQUES CNRS (CRLAO), EHESS ABSTRACT Tibetan verbal morphology differs considerably from that of other Sino-Tibetan languages. Most of the vocalic and consonantal alternations observed in the verbal paradigms remain unexplained after more than a hundred years of investigation: the study of historical Tibetan morphology would seem to have reached an aporia. This paper proposes a new model, explaining the origin of the alternations in the Tibetan verb as the remnant of a former system of directional prefixes, typologically similar to the ones still attested in the Rgyalrongic languages. 1. INTRODUCTION Tibetan verbal morphology is known for its extremely irregular conjugations. Li (1933) and Coblin (1976) have successfully explained some of the vocalic and consonantal alternations in the verbal system as the result of a series of sound changes. Little substantial progress has been made since Coblin’s article, except for Hahn (1999) and Hill (2005) who have discovered two additional conjugation patterns, the l- and r- stems respectively. Unlike many Sino-Tibetan languages (see for instance DeLancey 2010), Tibetan does not have verbal agreement, and its morphology seems mostly unrelated to that of other languages. Only three morphological features of the Tibetan verbal system have been compared with other languages. First, Shafer (1951: 1022) has proposed that the a ⁄ o alternation in the imperative was related to the –o suffix in Tamangic languages. This hypothesis is well accepted, though Zeisler (2002) has shown that the so-called imperative (skul-tshig) was not an imperative at all but a potential in Old Tibetan. -

7=SINO-INDIAN Phylosector

7= SINO-INDIAN phylosector Observatoire Linguistique Linguasphere Observatory page 525 7=SINO-INDIAN phylosector édition princeps foundation edition DU RÉPERTOIRE DE LA LINGUASPHÈRE 1999-2000 THE LINGUASPHERE REGISTER 1999-2000 publiée en ligne et mise à jour dès novembre 2012 published online & updated from November 2012 This phylosector comprises 22 sets of languages spoken by communities in eastern Asia, from the Himalayas to Manchuria (Heilongjiang), constituting the Sino-Tibetan (or Sino-Indian) continental affinity. See note on nomenclature below. 70= TIBETIC phylozone 71= HIMALAYIC phylozone 72= GARIC phylozone 73= KUKIC phylozone 74= MIRIC phylozone 75= KACHINIC phylozone 76= RUNGIC phylozone 77= IRRAWADDIC phylozone 78= KARENIC phylozone 79= SINITIC phylozone This continental affinity is composed of two major parts: the disparate Tibeto-Burman affinity (zones 70= to 77=), spoken by relatively small communities (with the exception of 77=) in the Himalayas and adjacent regions; and the closely related Chinese languages of the Sinitic set and net (zone 79=), spoken in eastern Asia. The Karen languages of zone 78=, formerly considered part of the Tibeto-Burman grouping, are probably best regarded as a third component of Sino-Tibetan affinity. Zone 79=Sinitic includes the outer-language with the largest number of primary voices in the world, representing the most populous network of contiguous speech-communities at the end of the 20th century ("Mainstream Chinese" or so- called 'Mandarin', standardised under the name of Putonghua). This phylosector is named 7=Sino-Indian (rather than Sino-Tibetan) to maintain the broad geographic nomenclature of all ten sectors of the linguasphere, composed of the names of continental or sub-continental entities. -

Vocabulary of Shingnyag Tibetan: a Dialect of Amdo Tibetan Spoken in Lhagang, Khams Minyag

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Prometheus-Academic Collections Asian and African Languages and Linguistics No.11, 2017 Vocabulary of Shingnyag Tibetan: A Dialect of Amdo Tibetan Spoken in Lhagang, Khams Minyag Suzuki, Hiroyuki IKOS, Universitetet i Oslo / National Museum of Ethnology Sonam Wangmo IKOS, Universitetet i Oslo Lhagang Town, located in Kangding Municipality, Ganzi Prefecture, Sichuan Province, China, is inhabited by many Tibetan pastoralists speaking varieties which are similar to Amdo Tibetan even though it is located at the Minyag Rabgang region of Khams, based on the Tibetan traditional geography. Among the multiple varieties spoken by inhabitants living in Lhagang Town, the Shingyag dialect is spoken in the south-western part of the town. It is somewhat different from other Amdo varieties spoken in Lhagang Town in the phonetic and phonological aspects. This article provides a word list with ca. 1500 words of Shingnyag Tibetan. Keywords: Amdo Tibetan, Minyag Rabgang, dialectology, migration pattern 1. Introduction 2. Phonological overview of Shingnyag Tibetan 3. Principal phonological features of Shingnyag Tibetan 1. Introduction This article aims to provide a word list (including ca. 1500 entries) with a phonological sketch of Shingnyag Tibetan, spoken in Xiya [Shing-nyag]1 Hamlet, located in the south-western part of Tagong [lHa-sgang] Town (henceforth Lhagang Town), Kangding [Dar-mdo] Municipality, Ganzi [dKar-mdzes] Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Sichuan Province, China (see Figure 1). Lhagang Town is in the easternmost part of Khams based on the traditional Tibetan geography, however, it is inhabited by many Tibetans whose mother tongue is Amdo Tibetan.2 Referring to Qu and Jin (1981), we can see that it is already known that Amdo-speaking Tibetans live in Suzuki, Hiroyuki and Sonam Wangmo. -

Syntactic Aspects of Nominalization in Five Tibeto-Burman Languages of the Himalayan Area1

Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area Volume 31.2 — October 2008 SYNTACTIC ASPECTS OF NOMINALIZATION IN FIVE TIBETO-BURMAN LANGUAGES OF THE HIMALAYAN AREA1 Carol Genetti University of California, Santa Barbara Research Centre for Linguistic Typology A.R. Coupe Ellen Bartee Kristine Hildebrandt You-Jing Lin La Trobe University SIL SIUE UC Santa Barbara The goal of this paper is to describe some of the syntactic structures that are created through nominalization processes in Himalayan Tibeto-Burman languages and the relationships between those structures. These include both structures involving the nominalization of clauses (e.g. complement clauses, relative clauses) and structures involving the nominalization of verbs and predicates (e.g. the derivation of nouns and adjectives). We will argue that, synchronically, clausal nominalization, structurally represented as [clause]NP, is the basic structure underlying many of the nominalizing constructions in these languages, even though individual constructions embed and alter this structure in interesting ways. In addition to clausal nominalization, we will illustrate the presence of derivational nominalization, represented as [V-NOM]N and [V-NOM]ADJ, although some nominal derivations target the predicate, not the verb root as their domain. We will also demonstrate that derivational nominalization can be seen as having developed from clausal nominalization, at least for some forms in some languages, and that the opposite direction of development, from derivational to clausal structures, is also attested. We will conclude with some syntactic observations pertinent to recent claims made on the historical relationship between nominalization and relativization, demonstrating that there are various ways that these structures can be related. -

)53Lt- I'\.' -- the ENGLISH and FOREIGN LANGUAGES UNIVERSITY HYDERABAD 500605, INDIA

DZONGKHA SEGMENTS AND TONES: A PHONETIC AND PHONOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION KINLEY DORJEE . I Supervisor PROFESSOR K.G. VIJA Y AKRISHNAN Department of Linguistics and Contemporary English Hyderabad Co-supervisor Dr. T. Temsunungsang The English and Foreign Languages University Shillong Campus A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics SCHOOL OF LANGUAGE SCIENCES >. )53lt- I'\.' -- THE ENGLISH AND FOREIGN LANGUAGES UNIVERSITY HYDERABAD 500605, INDIA JULY 2011 To my mother ABSTRACT In this thesis, we make, for the first time, an acoustic investigation of supposedly unique phonemic contrasts: a four-way stop phonation contrast (voiceless, voiceless aspirated, voiced and devoiced), a three-way fricative contrast (voiceless, voiced and devoiced) and a two-way sonorant contrast (voiced and voiceless) in Dzongkha, a Tibeto-Burman language spoken in Western Bhutan. Paying special attention to the 'Devoiced' (as recorded in the literature) obstruent and the 'Voiceless' sonorants, we examine the durational and spectral characteristics, including the vowel quality (following the initial consonant types), in comparison with four other languages, viz .. Hindi. Korean (for obstruents), Mizo and Tenyidie (for sonorants). While the 'devoiced' phonation type in Dzongkha is not attested in any language in the region, we show that the devoiced type is very different from the 'breathy' phonation type, found in Hindi. However, when compared to the three-way voiceless stop phonation types (Tense, Lax and Aspirated) in Korean, we find striking similarities in the way the two stops CDevoiced' and 'Lax') employ their acoustic correlates. We extend our analysis of stops to fricatives, and analyse the three fricatives in Dzongkha as: Tense, Lax and Voiced. -

Review of Evidential Systems of Tibetan Languages

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2017 Review of Lauren Gawne Nathan W. Hill (eds.). 2016. Evidential systems of Tibetan languages. Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area 40(2), 285–303 Widmer, Manuel DOI: https://doi.org/10.1075/ltba.00002.wid Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-168681 Journal Article Accepted Version Originally published at: Widmer, Manuel (2017). Review of Lauren Gawne Nathan W. Hill (eds.). 2016. Evidential systems of Tibetan languages. Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area 40(2), 285–303. Linguistics of the Tibeto- Burman Area, 40(2):285-303. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1075/ltba.00002.wid Review of Evidential systems of Tibetan languages Gawne, Lauren & Nathan W. Hill (eds.). 2016. Evidential systems of Tibetan languages. de Gruyter: Berlin. vi + 472 pp. ISBN 978-3-11-047374-2 Reviewed by Manuel Widmer 1 Tibetan evidentiality systems and their relevance for the typology of evidentiality The evidentiality1 systems of Tibetan languages rank among the most complex in the world. According to Tournadre & Dorje (2003: 110), the evidentiality systeM of Lhasa Tibetan (LT) distinguishes no less than four “evidential Moods”: (i) egophoric, (ii) testiMonial, (iii) inferential, and (iv) assertive. If one also takes into account the hearsay Marker, which is cOMMonly considered as an evidential category in typological survey studies (e.g. Aikhenvald 2004; Hengeveld & Dall’Aglio Hattnher 2015; inter alia), LT displays a five-fold evidential distinction. The LT systeM, however, is clearly not the Most cOMplex of its kind within the Tibetan linguistic area. -

Himalayan Linguistics the Encoding Of

Himalayan Linguistics The encoding of space in Manange and Nar-Phu (Tamangic) Kristine A. Hildebrandt Southern Illinois University Edwardsville ABSTRACT This is an account of the forms and semantic dimensions of spatial relations in Manange (Tibeto-Burman, Tamangic; Nepal), with comparison to sister language Nar-Phu. Topological relations (“IN/ON/AT/ NEAR”) in these languages are encoded by locative enclitics and also by a set of noun-like objects termed as “locational nouns.” In Manange, the general locative enclitic is more frequently encountered for a wide range of topological relations, while in Nar-Phu, the opposite pattern is observed, i.e. more frequent use of locational nouns. While the linguistic frame of reference system encoded in these forms is primarily relative (i.e. oriented on the speaker’s own viewing perspective), a more extrinsic/absolute system emerges with certain verbs of motion in these languages, with verbs like “come,” “go,” and certain verbs of placement or posture orienting to arbitrary fixed bearings such as slope. This account also provides some examples of cultural or metaphorical extensions of spatial forms as they are encountered in connected speech. KEYWORDS Tamangic, directional, static, dynamic, locational noun, relative, intrinsic, absolute This is a contribution from Himalayan Linguistics, Vol. 16(1), Special Issue on the Grammatical Encoding of Space, Carol Genetti and Kristine Hildebrandt (eds.): 41-58. ISSN 1544-7502 © 2017. All rights reserved. This Portable Document Format (PDF) file may not be altered in any way. Tables of contents, abstracts, and submission guidelines are available at escholarship.org/uc/himalayanlinguistics Himalayan Linguistics, Vol. 16(1). -

A Guide to the Syuba (Kagate) Language Documentation Corpus

Vol. 12 (2018), pp. 204–234 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24768 Revised Version Received: 17 Jan 2018 A Guide to the Syuba (Kagate) Language Documentation Corpus Lauren Gawne SOAS University of London La Trobe University This article provides an overview of the collection “Kagate (Syuba)”, archived with both the Pacific and Regional Archive for Digital Sources in Endangered Cultures (PARADISEC) and the Endangered Language Archive (ELAR). It pro- vides an overview of the materials that have been archived, as well as details of the workflow, conventions used, and structure of the collection. It also provides context for the content of the collection, including an overview of the language context, and some of the motivations behind the documentation project. This article thus provides an entry point to the collection. The future plans for the collection – from the perspectives of both the researcher and Syuba speakers – are also outlined, but with the overwhelming majority of items in the collection available to others, it is hoped that this article will encourage use of the materials by other researchers. 1. Introduction Language documentation involves the development of corpora of materials from which descriptions of grammar and language use can be developed, alongside other uses of the materials by both speakers of the language and researchers. Himmelmann (1998) argues that language documentation and description are two distinct, but interrelated, activities. In reality, the majority of basic linguistic descrip- tion based on primary data is undertaken by the same person who collected the data. Very little of this descriptive work makes clear the nature of the data on which it is built; in a survey of 50 published grammars and 50 PhD dissertations, Gawne et al. -

PPD Talk by Prof. Nicolas Tournadre

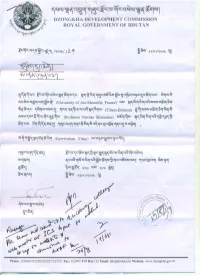

-. '" ~~Q.l·~~·q~~·~~~·~,,·rq·~,,·qt4Q.l·~~·l~~l DZONGKHA DEVELOPMENT COMMISSION ROYAL GOVERNMENT OF BHUTAN "'~=<~r\"~\"\~T"""""'" ..~ D. oN' qJ{, n..,~~V){"\ ..."."" ~ t ,. '" '" '" -.r '" 7::F. '" C\.. '" C\.. '" C\ '" '" '" ~.~~.~.u-yz:::..~z:::..(tI.~z:::..~t4QJ.~~.ct:l~~.~z:::~~·~·"~·~~z:::.·o-!sa·,,o-!·~z::r:Ir~~~·o-!~o-!·~r:;r·sa~·QJ~·.~~~.~.. ~".~QJ.~~~.QJ~.~r:;r.~. (University of Aix-Marseille, France) QJ~' ~~.~~.~~.t.lq.o-!(tI~.~~~.~~. C\..C\.. C\.. C\.. C\.. C\.. C\.. ",C\C\..C\.. ~~'~'~z:::.' ~~~~'r:;r~QJ'~' ~z:::.~·-o~·7·o-!·QJ·u-y~·~~·,,~~·(Tibeto-Bunnan) ~.~.~(tI~.~a:;~.-o~.~~.o-!. C\..-.r '" C\.. '" C\.. C\.. C\.. C\.. '" C\.. ~(tI~.~r:;rz:::..~."l.QJ.~".~~.~~.(Professor Nicolas 'J:oumadre) o-!a:;~'~~' ~~·u-y~·,,~·t.I~·~S·~~~·~· '" '" C\..'" C\..C\.. C\.. C\ '" '" sa~'QJ~' ~~.~.~~.~~.~. ~~z:::.·r:;r4~·~~z:::.·~·~~·o-!·~~·~z:::.·r~r~S~·~~z:::.·~·r:;r·o-!~~1r '" '" C\.. '" C\.. C\..-.r '" ~~z:::.·r:;r4~·~~·~~1 ~z:::..(tI.~z:::..a:;~.~~.~.~".~~.~~·o-!z:::.·o-!·u-y~·t.I~·~z:::.·~C4QJl ~'~~~1 ~z:::.'t.Iq·~'*r:;r·~~·t.lq·~r:;r·l~~·~·'1QJ·~i!~~·(tIz:::.l"l·'1:fz:::.'Sz:::.·~1a5.J·~~ ~l~l ~o-!'~l~' ~:~o QJ~' l{.:oo ~~l C\..~ a;~·:uz:::.~1 ~'a:l~' '.l...'.l...lo"I'.l...o'}~ ~l 4~·"r:;r·~QJ·o-!~~1 '" §z:::.·a:;~1 Phone: 322663/325226/325227/323721 Fax: 322992 P.O Box 122 Email: [email protected] Website: www.dzongkha.gov.bt Nicolas Tournadre's Curriculum Vitae Name: Nicolas Toumadre / '",?~.q~"'a:;~.~.q~~. Professor at the University of Aix-Marseille, linguistics department CN~~r~r"'- aI~:~llrmJ::r~ra5~'a,- ~l·~~II ""·qc:rc5~·~~ l~'ifl~"- 'a5~'aII E~ail : [email protected] Professional site: www.nicolas-tournadre.net Education 1984 MA in Russian Literature, Sorbonne University 1987 BA in Tibetan language and civilisation, Institute of Oriental Languages and Civilisation (INalco, Paris) 1989 Louis Forest prize-winning awarded by the "Chancellerie des Universites de Paris". -

Herever Possible

Published by Department of Information and International Relations (DIIR) Central Tibetan Administration Dharamshala-176215 H.P. India Email: [email protected] www.tibet.net Copyright © DIIR 2018 First edition: October 2018 1000 copies ISBN-978-93-82205-12-8 Design & Layout: Kunga Phuntsok / DIIR Printed at New Delhi: Norbu Graphics CONTENTS Foreword------------------------------------------------------------------1 Chapter One: Burning Tibet: Self-immolation Protests in Tibet---------------------5 Chapter Two: The Historical Status of Tibet-------------------------------------------37 Chapter Three: Human Rights Situation in Tibet--------------------------------------69 Chapter Four: Cultural Genocide in Tibet--------------------------------------------107 Chapter Five: The Tibetan Plateau and its Deteriorating Environment---------135 Chapter Six: The True Nature of Economic Development in Tibet-------------159 Chapter Seven: China’s Urbanization in Tibet-----------------------------------------183 Chapter Eight: China’s Master Plan for Tibet: Rule by Reincarnation-------------197 Chapter Nine: Middle Way Approach: The Way Forward--------------------------225 FOREWORD For Tibetans, information is a precious commodity. Severe restric- tions on expression accompanied by a relentless disinformation campaign engenders facts, knowledge and truth to become priceless. This has long been the case with Tibet. At the time of the publication of this report, Tibet has been fully oc- cupied by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) for just five months shy of sixty years. As China has sought to develop Tibet in certain ways, largely economically and in Chinese regions, its obsessive re- strictions on the flow of information have only grown more intense. Meanwhile, the PRC has ready answers to fill the gaps created by its information constraints, whether on medieval history or current growth trends. These government versions of the facts are backed ever more fiercely as the nation’s economic and military power grows.