Tibet's Minority Languages-Diversity and Endangerment-Appendix 9 28 Sept Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Origins and Consequences of Kin Networks and Marriage Practices

The origins and consequences of kin networks and marriage practices by Duman Bahramirad M.Sc., University of Tehran, 2007 B.Sc., University of Tehran, 2005 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Economics Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences c Duman Bahramirad 2018 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2018 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Approval Name: Duman Bahramirad Degree: Doctor of Philosophy (Economics) Title: The origins and consequences of kin networks and marriage practices Examining Committee: Chair: Nicolas Schmitt Professor Gregory K. Dow Senior Supervisor Professor Alexander K. Karaivanov Supervisor Professor Erik O. Kimbrough Supervisor Associate Professor Argyros School of Business and Economics Chapman University Simon D. Woodcock Supervisor Associate Professor Chris Bidner Internal Examiner Associate Professor Siwan Anderson External Examiner Professor Vancouver School of Economics University of British Columbia Date Defended: July 31, 2018 ii Ethics Statement iii iii Abstract In the first chapter, I investigate a potential channel to explain the heterogeneity of kin networks across societies. I argue and test the hypothesis that female inheritance has historically had a posi- tive effect on in-marriage and a negative effect on female premarital relations and economic partic- ipation. In the second chapter, my co-authors and I provide evidence on the positive association of in-marriage and corruption. We also test the effect of family ties on nepotism in a bribery experi- ment. The third chapter presents my second joint paper on the consequences of kin networks. -

Annual Report 2005

Annual Report 2005 NSW Department of Education and Training Published by Strategic Planning and Regulation NSW Department of Education and Training (DET) 35 Bridge Street Sydney NSW 2000 ISSN 1442-3898 The Annual Report is available from Planning and Innovation Directorate, DET Level 5, 35 Bridge Street, Sydney NSW 2000, and online from: www.det.nsw.edu.au/annualreports The estimated cost of production and printing the publication was $26,300. The Department’s office hours are from 9:00am to 5:00pm Monday to Friday. State, Regional and Institute office addresses and telephone numbers are listed on the inside back cover. Cover Photo Northern Beaches Secondary College. This college was awarded the NSW VET Excellence Award. Letter of Submission to the Minister The Hon Ms Carmel Tebbutt MP Minister for Education and Training Level 33, Governor Macquarie Tower 1 Farrer Place SYDNEY NSW 2000 Dear Minister It is with pleasure that I submit the annual report of the NSW Department of Education and Training for the year ended 31 December 2005. The report has been prepared in accordance with the requirements of the Annual Reports (Departments) Act 1985 and the Public Finance and Audit Act 1983 and regulations under those Acts, and it is submitted to you for presentation to the NSW Parliament. This report contains details of the Department’s performance in implementing strategic priorities in NSW public schools, TAFE NSW, Adult and Community Education, Adult Migrant English Services, higher education and the National Art School. It also contains the Department’s audited financial statements for the year ended 30 June 2005. -

Vocabulary of Shingnyag Tibetan: a Dialect of Amdo Tibetan Spoken in Lhagang, Khams Minyag

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Prometheus-Academic Collections Asian and African Languages and Linguistics No.11, 2017 Vocabulary of Shingnyag Tibetan: A Dialect of Amdo Tibetan Spoken in Lhagang, Khams Minyag Suzuki, Hiroyuki IKOS, Universitetet i Oslo / National Museum of Ethnology Sonam Wangmo IKOS, Universitetet i Oslo Lhagang Town, located in Kangding Municipality, Ganzi Prefecture, Sichuan Province, China, is inhabited by many Tibetan pastoralists speaking varieties which are similar to Amdo Tibetan even though it is located at the Minyag Rabgang region of Khams, based on the Tibetan traditional geography. Among the multiple varieties spoken by inhabitants living in Lhagang Town, the Shingyag dialect is spoken in the south-western part of the town. It is somewhat different from other Amdo varieties spoken in Lhagang Town in the phonetic and phonological aspects. This article provides a word list with ca. 1500 words of Shingnyag Tibetan. Keywords: Amdo Tibetan, Minyag Rabgang, dialectology, migration pattern 1. Introduction 2. Phonological overview of Shingnyag Tibetan 3. Principal phonological features of Shingnyag Tibetan 1. Introduction This article aims to provide a word list (including ca. 1500 entries) with a phonological sketch of Shingnyag Tibetan, spoken in Xiya [Shing-nyag]1 Hamlet, located in the south-western part of Tagong [lHa-sgang] Town (henceforth Lhagang Town), Kangding [Dar-mdo] Municipality, Ganzi [dKar-mdzes] Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Sichuan Province, China (see Figure 1). Lhagang Town is in the easternmost part of Khams based on the traditional Tibetan geography, however, it is inhabited by many Tibetans whose mother tongue is Amdo Tibetan.2 Referring to Qu and Jin (1981), we can see that it is already known that Amdo-speaking Tibetans live in Suzuki, Hiroyuki and Sonam Wangmo. -

Dissertation JIAN 2016 Final

The Impact of Global English in Xinjiang, China: Linguistic Capital and Identity Negotiation among the Ethnic Minority and Han Chinese Students Ge Jian A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2016 Reading Committee: Laada Bilaniuk, Chair Ann Anagnost, Chair Stevan Harrell Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Anthropology © Copyright 2016 Ge Jian University of Washington Abstract The Impact of Global English in Xinjiang, China: Linguistic Capital and Identity Negotiation among the Ethnic Minority and Han Chinese Students Ge Jian Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Laada Bilaniuk Professor Ann Anagnost Department of Anthropology My dissertation is an ethnographic study of the language politics and practices of college- age English language learners in Xinjiang at the historical juncture of China’s capitalist development. In Xinjiang the international lingua franca English, the national official language Mandarin Chinese, and major Turkic languages such as Uyghur and Kazakh interact and compete for linguistic prestige in different social scenarios. The power relations between the Turkic languages, including the Uyghur language, and Mandarin Chinese is one in which minority languages are surrounded by a dominant state language supported through various institutions such as school and mass media. The much greater symbolic capital that the “legitimate language” Mandarin Chinese carries enables its native speakers to have easier access than the native Turkic speakers to jobs in the labor market. Therefore, many Uyghur parents face the dilemma of choosing between maintaining their cultural and linguistic identity and making their children more socioeconomically mobile. The entry of the global language English and the recent capitalist development in China has led to English education becoming market-oriented and commodified, which has further complicated the linguistic picture in Xinjiang. -

Aktionsart and Aspect in Qiang

The 2005 International Course and Conference on RRG, Academia Sinica, Taipei, June 26-30 AKTIONSART AND ASPECT IN QIANG Huang Chenglong Institute of Ethnology & Anthropology Chinese Academy of Social Sciences E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The Qiang language reflects a basic Aktionsart dichotomy in the classification of stative and active verbs, the form of verbs directly reflects the elements of the lexical decomposition. Generally, State or activity is the basic form of the verb, which becomes an achievement or accomplishment when it takes a directional prefix, and becomes a causative achievement or causative accomplishment when it takes the causative suffix. It shows that grammatical aspect and Aktionsart seem to play much of a systematic role. Semantically, on the one hand, there is a clear-cut boundary between states and activities, but morphologically, however, there is no distinction between them. Both of them take the same marking to encode lexical aspect (Aktionsart), and grammatical aspect does not entirely correspond with lexical aspect. 1.0. Introduction The Ronghong variety of Qiang is spoken in Yadu Township (雅都鄉), Mao County (茂縣), Aba Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture (阿壩藏族羌族自治州), Sichuan Province (四川省), China. It has more than 3,000 speakers. The Ronghong variety of Qiang belongs to the Yadu subdialect (雅都土語) of the Northern dialect of Qiang (羌語北部方言). It is mutually intelligible with other subdialects within the Northern dialect, but mutually unintelligible with other subdialects within the Southern dialect. In this paper we use Aktionsart and lexical decomposition, as developed by Van Valin and LaPolla (1997, Ch. 3 and Ch. 4), to discuss lexical aspect, grammatical aspect and the relationship between them in Qiang. -

Review of Evidential Systems of Tibetan Languages

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2017 Review of Lauren Gawne Nathan W. Hill (eds.). 2016. Evidential systems of Tibetan languages. Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area 40(2), 285–303 Widmer, Manuel DOI: https://doi.org/10.1075/ltba.00002.wid Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-168681 Journal Article Accepted Version Originally published at: Widmer, Manuel (2017). Review of Lauren Gawne Nathan W. Hill (eds.). 2016. Evidential systems of Tibetan languages. Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area 40(2), 285–303. Linguistics of the Tibeto- Burman Area, 40(2):285-303. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1075/ltba.00002.wid Review of Evidential systems of Tibetan languages Gawne, Lauren & Nathan W. Hill (eds.). 2016. Evidential systems of Tibetan languages. de Gruyter: Berlin. vi + 472 pp. ISBN 978-3-11-047374-2 Reviewed by Manuel Widmer 1 Tibetan evidentiality systems and their relevance for the typology of evidentiality The evidentiality1 systems of Tibetan languages rank among the most complex in the world. According to Tournadre & Dorje (2003: 110), the evidentiality systeM of Lhasa Tibetan (LT) distinguishes no less than four “evidential Moods”: (i) egophoric, (ii) testiMonial, (iii) inferential, and (iv) assertive. If one also takes into account the hearsay Marker, which is cOMMonly considered as an evidential category in typological survey studies (e.g. Aikhenvald 2004; Hengeveld & Dall’Aglio Hattnher 2015; inter alia), LT displays a five-fold evidential distinction. The LT systeM, however, is clearly not the Most cOMplex of its kind within the Tibetan linguistic area. -

THE SECURITISATION of TIBETAN BUDDHISM in COMMUNIST CHINA Abstract

ПОЛИТИКОЛОГИЈА РЕЛИГИЈЕ бр. 2/2012 год VI • POLITICS AND RELIGION • POLITOLOGIE DES RELIGIONS • Nº 2/2012 Vol. VI ___________________________________________________________________________ Tsering Topgyal 1 Прегледни рад Royal Holloway University of London UDK: 243.4:323(510)”1949/...” United Kingdom THE SECURITISATION OF TIBETAN BUDDHISM IN COMMUNIST CHINA Abstract This article examines the troubled relationship between Tibetan Buddhism and the Chinese state since 1949. In the history of this relationship, a cyclical pattern of Chinese attempts, both violently assimilative and subtly corrosive, to control Tibetan Buddhism and a multifaceted Tibetan resistance to defend their religious heritage, will be revealed. This article will develop a security-based logic for that cyclical dynamic. For these purposes, a two-level analytical framework will be applied. First, the framework of the insecurity dilemma will be used to draw the broad outlines of the historical cycles of repression and resistance. However, the insecurity dilemma does not look inside the concept of security and it is not helpful to establish how Tibetan Buddhism became a security issue in the first place and continues to retain that status. The theory of securitisation is best suited to perform this analytical task. As such, the cycles of Chinese repression and Tibetan resistance fundamentally originate from the incessant securitisation of Tibetan Buddhism by the Chinese state and its apparatchiks. The paper also considers the why, how, and who of this securitisation, setting the stage for a future research project taking up the analytical effort to study the why, how and who of a potential desecuritisation of all things Tibetan, including Tibetan Buddhism, and its benefits for resolving the protracted Sino- Tibetan conflict. -

Day 1: Handouts (Tibet)

Handout One: Introducing Tibet [With Country Names] First, let’s look at this world map. Find the United States. Now let’s find China! Tibet is a region within China. This is a map of Tibet’s six prefectures and its capital city, Lhasa. On the map of China below, find Tibet. What color is Tibet on this map? Did you find it? [Teacher’s Key] Handout One: Introducing Tibet [Without Country Names] First, let’s look at this world map. Find the United States. Now let’s find China! Hint: It’s light green! Tibet is a region within China. This is a map of Tibet’s six prefectures and its capital city, Lhasa. On the map of China below, find Tibet. What color is Tibet on this map? Did you find it? [Teacher’s Key] Handout Two: Quick Facts about Tibet and the Tibet Autonomous Region ★ Tibet is historically made up of three provinces of Amdo, Kham and U-Tsang. It was split up by the People’s Republic of China. The main Tibetan region now is the Tibet Autonomous Region. ★ The Tibet Autonomous Region, is a province within the People’s Republic of China. ★ Before 1950, Tibet was an independent country, but China invaded the country and took over. ★ The capital of the Tibet Autonomous Region is Lhasa. ★ The official language of the Tibet Autonomous Region is Lhasa Tibetan. ○ In schools, children are also taught Mandarin Chinese. ★ The main religion among the Tibetan people is Tibetan Buddhism. ★ In 1959, the Dalai Lama and 80,000 Tibetans fled to India for their safety. -

Rise of the Veil: Islamic Modernity and the Hui Woman Zainab Khalid SIT Study Abroad

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Spring 2011 Rise of the Veil: Islamic Modernity and the Hui Woman Zainab Khalid SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, History of Religions of Eastern Origins Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Khalid, Zainab, "Rise of the Veil: Islamic Modernity and the Hui Woman" (2011). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 1074. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/1074 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rise of the Veil: Islamic Modernity and the Hui Woman Zainab Khalid SIT FALL 2011 5/1/2011 1 Introduction: Assimilation/Dissimilation The Hui are a familiar sight in most cities in China; famed for their qingzhen restaurants and their business acumen. Known usually as the “Chinese speaking Muslims,” they are separated from the nine other Muslim xiaoshu minzu by a reputation for assimilation and adaptability that is a matter of pride for Hui in urban areas. A conversation with Hui women at Nancheng Mosque in Kunming revealed that they believed Hui to be at an advantage compared to other xiaoshu minzu because of their abilities to adapt and assimilate, “we are intelligent; we know what to do in order to survive in any environment.” Yet, the Hui of Yunnan also have a history of dissimilation- the Panthay Rebellion of 1856 took the shape of a Sultanate in Dali as Hui forces led a province-wide revolt against the Qing Empire. -

"Brightening" and the Place of Xixia (Tangut)

1 "Briiighttteniiing" and ttthe plllace of Xiiixiiia (Tanguttt) iiin ttthe Qiiiangiiic branch of Tiiibettto-Burman* James A. Matisoff University of California, Berkeley 1.0 Introduction Xixia (Tangut) is an extinct Tibeto-Burman language, once spoken in the Qinghai/Gansu/Tibetan border region in far western China. Its complex logographic script, invented around A.D. 1036, was the vehicle for a considerable body of literature until it gradually fell out of use after the Mongol conquest in 1223 and the destruction of the Xixia kingdom.1 A very large percentage of the 6000+ characters have been semantically deciphered and phonologically reconstructed, thanks to a Xixia/Chinese glossary, Tibetan transcriptions, and monolingual Xixia dictionaries and rhyme-books. The f«anqi\e method of indicating the pronunciation of Xixia characters was used both via other Xixia characters (in the monolingual dictionaries) and via Chinese characters (in the bilingual glossary Pearl in the Palm, where Chinese characters are also glossed by one or more Xixia ones). Various reconstruction systems have been proposed by scholars, including M.V. Sofronov/K.B. Keping, T. Nishida, Li Fanwen, and Gong Hwang-cherng. This paper relies entirely on the reconstructions of Gong.2 After some initial speculations that Xixia might have belonged to the Loloish group of Tibeto-Burman languages, scholarly opinion has now coalesced behind the geographically plausible opinion that it was a member of the "Qiangic" subgroup of TB. The dozen or so Qiangic languages, spoken in Sichuan Province and adjacent parts of Yunnan, were once among the most obscure in the TB family, loosely lumped together as the languages of the Western Barbarians (Xifan = Hsifan). -

PPD Talk by Prof. Nicolas Tournadre

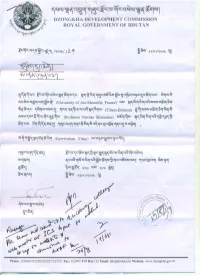

-. '" ~~Q.l·~~·q~~·~~~·~,,·rq·~,,·qt4Q.l·~~·l~~l DZONGKHA DEVELOPMENT COMMISSION ROYAL GOVERNMENT OF BHUTAN "'~=<~r\"~\"\~T"""""'" ..~ D. oN' qJ{, n..,~~V){"\ ..."."" ~ t ,. '" '" '" -.r '" 7::F. '" C\.. '" C\.. '" C\ '" '" '" ~.~~.~.u-yz:::..~z:::..(tI.~z:::..~t4QJ.~~.ct:l~~.~z:::~~·~·"~·~~z:::.·o-!sa·,,o-!·~z::r:Ir~~~·o-!~o-!·~r:;r·sa~·QJ~·.~~~.~.. ~".~QJ.~~~.QJ~.~r:;r.~. (University of Aix-Marseille, France) QJ~' ~~.~~.~~.t.lq.o-!(tI~.~~~.~~. C\..C\.. C\.. C\.. C\.. C\.. C\.. ",C\C\..C\.. ~~'~'~z:::.' ~~~~'r:;r~QJ'~' ~z:::.~·-o~·7·o-!·QJ·u-y~·~~·,,~~·(Tibeto-Bunnan) ~.~.~(tI~.~a:;~.-o~.~~.o-!. C\..-.r '" C\.. '" C\.. C\.. C\.. C\.. '" C\.. ~(tI~.~r:;rz:::..~."l.QJ.~".~~.~~.(Professor Nicolas 'J:oumadre) o-!a:;~'~~' ~~·u-y~·,,~·t.I~·~S·~~~·~· '" '" C\..'" C\..C\.. C\.. C\ '" '" sa~'QJ~' ~~.~.~~.~~.~. ~~z:::.·r:;r4~·~~z:::.·~·~~·o-!·~~·~z:::.·r~r~S~·~~z:::.·~·r:;r·o-!~~1r '" '" C\.. '" C\.. C\..-.r '" ~~z:::.·r:;r4~·~~·~~1 ~z:::..(tI.~z:::..a:;~.~~.~.~".~~.~~·o-!z:::.·o-!·u-y~·t.I~·~z:::.·~C4QJl ~'~~~1 ~z:::.'t.Iq·~'*r:;r·~~·t.lq·~r:;r·l~~·~·'1QJ·~i!~~·(tIz:::.l"l·'1:fz:::.'Sz:::.·~1a5.J·~~ ~l~l ~o-!'~l~' ~:~o QJ~' l{.:oo ~~l C\..~ a;~·:uz:::.~1 ~'a:l~' '.l...'.l...lo"I'.l...o'}~ ~l 4~·"r:;r·~QJ·o-!~~1 '" §z:::.·a:;~1 Phone: 322663/325226/325227/323721 Fax: 322992 P.O Box 122 Email: [email protected] Website: www.dzongkha.gov.bt Nicolas Tournadre's Curriculum Vitae Name: Nicolas Toumadre / '",?~.q~"'a:;~.~.q~~. Professor at the University of Aix-Marseille, linguistics department CN~~r~r"'- aI~:~llrmJ::r~ra5~'a,- ~l·~~II ""·qc:rc5~·~~ l~'ifl~"- 'a5~'aII E~ail : [email protected] Professional site: www.nicolas-tournadre.net Education 1984 MA in Russian Literature, Sorbonne University 1987 BA in Tibetan language and civilisation, Institute of Oriental Languages and Civilisation (INalco, Paris) 1989 Louis Forest prize-winning awarded by the "Chancellerie des Universites de Paris". -

Himalayan Languages and Linguistics: Studies in Phonology, Semantics, Morphology and Syntax by Mark Turin and Bettina Zeisler, Eds.; Reviewed by Elena Bashir

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 31 Number 1 Article 21 8-1-2012 Himalayan Languages and Linguistics: Studies in Phonology, Semantics, Morphology and Syntax by Mark Turin and Bettina Zeisler, Eds.; Reviewed by Elena Bashir Elena Bashir University of Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Bashir, Elena. 2012. Himalayan Languages and Linguistics: Studies in Phonology, Semantics, Morphology and Syntax by Mark Turin and Bettina Zeisler, Eds.; Reviewed by Elena Bashir. HIMALAYA 31(1). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol31/iss1/21 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. This Review is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. In Part II, Helen Plaisier’s article, “A key to four HIMALAYAN LANGUAGES transcription systems of Lepcha” (13 pp.), compares transcription systems proposed by four scholars, including AND LINGUISTICS: STUDIES herself, and argues that her own system “offers the user the most accurate way of transcribing Lepcha. The transliteration IN PHONOLOGY, SEMANTICS, is consistent with and faithful to the way text is written in the traditional Lepcha orthography, so it remains possible at all times to derive the original spelling from the transliteration” MORPHOLOGY AND SYNTAX (p. 51). Y ARK URIN AND ETTINA EISLER Hiroyuki Suzuki’s paper is on “Dialectal particularities B M T B Z , of Sogpho Tibetan - an introduction to the “Twenty-four EDS.