Towards a New Approach to Evidentiality : Issues and Directions for Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vocabulary of Shingnyag Tibetan: a Dialect of Amdo Tibetan Spoken in Lhagang, Khams Minyag

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Prometheus-Academic Collections Asian and African Languages and Linguistics No.11, 2017 Vocabulary of Shingnyag Tibetan: A Dialect of Amdo Tibetan Spoken in Lhagang, Khams Minyag Suzuki, Hiroyuki IKOS, Universitetet i Oslo / National Museum of Ethnology Sonam Wangmo IKOS, Universitetet i Oslo Lhagang Town, located in Kangding Municipality, Ganzi Prefecture, Sichuan Province, China, is inhabited by many Tibetan pastoralists speaking varieties which are similar to Amdo Tibetan even though it is located at the Minyag Rabgang region of Khams, based on the Tibetan traditional geography. Among the multiple varieties spoken by inhabitants living in Lhagang Town, the Shingyag dialect is spoken in the south-western part of the town. It is somewhat different from other Amdo varieties spoken in Lhagang Town in the phonetic and phonological aspects. This article provides a word list with ca. 1500 words of Shingnyag Tibetan. Keywords: Amdo Tibetan, Minyag Rabgang, dialectology, migration pattern 1. Introduction 2. Phonological overview of Shingnyag Tibetan 3. Principal phonological features of Shingnyag Tibetan 1. Introduction This article aims to provide a word list (including ca. 1500 entries) with a phonological sketch of Shingnyag Tibetan, spoken in Xiya [Shing-nyag]1 Hamlet, located in the south-western part of Tagong [lHa-sgang] Town (henceforth Lhagang Town), Kangding [Dar-mdo] Municipality, Ganzi [dKar-mdzes] Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Sichuan Province, China (see Figure 1). Lhagang Town is in the easternmost part of Khams based on the traditional Tibetan geography, however, it is inhabited by many Tibetans whose mother tongue is Amdo Tibetan.2 Referring to Qu and Jin (1981), we can see that it is already known that Amdo-speaking Tibetans live in Suzuki, Hiroyuki and Sonam Wangmo. -

Review of Evidential Systems of Tibetan Languages

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2017 Review of Lauren Gawne Nathan W. Hill (eds.). 2016. Evidential systems of Tibetan languages. Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area 40(2), 285–303 Widmer, Manuel DOI: https://doi.org/10.1075/ltba.00002.wid Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-168681 Journal Article Accepted Version Originally published at: Widmer, Manuel (2017). Review of Lauren Gawne Nathan W. Hill (eds.). 2016. Evidential systems of Tibetan languages. Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area 40(2), 285–303. Linguistics of the Tibeto- Burman Area, 40(2):285-303. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1075/ltba.00002.wid Review of Evidential systems of Tibetan languages Gawne, Lauren & Nathan W. Hill (eds.). 2016. Evidential systems of Tibetan languages. de Gruyter: Berlin. vi + 472 pp. ISBN 978-3-11-047374-2 Reviewed by Manuel Widmer 1 Tibetan evidentiality systems and their relevance for the typology of evidentiality The evidentiality1 systems of Tibetan languages rank among the most complex in the world. According to Tournadre & Dorje (2003: 110), the evidentiality systeM of Lhasa Tibetan (LT) distinguishes no less than four “evidential Moods”: (i) egophoric, (ii) testiMonial, (iii) inferential, and (iv) assertive. If one also takes into account the hearsay Marker, which is cOMMonly considered as an evidential category in typological survey studies (e.g. Aikhenvald 2004; Hengeveld & Dall’Aglio Hattnher 2015; inter alia), LT displays a five-fold evidential distinction. The LT systeM, however, is clearly not the Most cOMplex of its kind within the Tibetan linguistic area. -

A Guide to the Syuba (Kagate) Language Documentation Corpus

Vol. 12 (2018), pp. 204–234 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24768 Revised Version Received: 17 Jan 2018 A Guide to the Syuba (Kagate) Language Documentation Corpus Lauren Gawne SOAS University of London La Trobe University This article provides an overview of the collection “Kagate (Syuba)”, archived with both the Pacific and Regional Archive for Digital Sources in Endangered Cultures (PARADISEC) and the Endangered Language Archive (ELAR). It pro- vides an overview of the materials that have been archived, as well as details of the workflow, conventions used, and structure of the collection. It also provides context for the content of the collection, including an overview of the language context, and some of the motivations behind the documentation project. This article thus provides an entry point to the collection. The future plans for the collection – from the perspectives of both the researcher and Syuba speakers – are also outlined, but with the overwhelming majority of items in the collection available to others, it is hoped that this article will encourage use of the materials by other researchers. 1. Introduction Language documentation involves the development of corpora of materials from which descriptions of grammar and language use can be developed, alongside other uses of the materials by both speakers of the language and researchers. Himmelmann (1998) argues that language documentation and description are two distinct, but interrelated, activities. In reality, the majority of basic linguistic descrip- tion based on primary data is undertaken by the same person who collected the data. Very little of this descriptive work makes clear the nature of the data on which it is built; in a survey of 50 published grammars and 50 PhD dissertations, Gawne et al. -

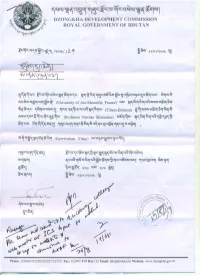

PPD Talk by Prof. Nicolas Tournadre

-. '" ~~Q.l·~~·q~~·~~~·~,,·rq·~,,·qt4Q.l·~~·l~~l DZONGKHA DEVELOPMENT COMMISSION ROYAL GOVERNMENT OF BHUTAN "'~=<~r\"~\"\~T"""""'" ..~ D. oN' qJ{, n..,~~V){"\ ..."."" ~ t ,. '" '" '" -.r '" 7::F. '" C\.. '" C\.. '" C\ '" '" '" ~.~~.~.u-yz:::..~z:::..(tI.~z:::..~t4QJ.~~.ct:l~~.~z:::~~·~·"~·~~z:::.·o-!sa·,,o-!·~z::r:Ir~~~·o-!~o-!·~r:;r·sa~·QJ~·.~~~.~.. ~".~QJ.~~~.QJ~.~r:;r.~. (University of Aix-Marseille, France) QJ~' ~~.~~.~~.t.lq.o-!(tI~.~~~.~~. C\..C\.. C\.. C\.. C\.. C\.. C\.. ",C\C\..C\.. ~~'~'~z:::.' ~~~~'r:;r~QJ'~' ~z:::.~·-o~·7·o-!·QJ·u-y~·~~·,,~~·(Tibeto-Bunnan) ~.~.~(tI~.~a:;~.-o~.~~.o-!. C\..-.r '" C\.. '" C\.. C\.. C\.. C\.. '" C\.. ~(tI~.~r:;rz:::..~."l.QJ.~".~~.~~.(Professor Nicolas 'J:oumadre) o-!a:;~'~~' ~~·u-y~·,,~·t.I~·~S·~~~·~· '" '" C\..'" C\..C\.. C\.. C\ '" '" sa~'QJ~' ~~.~.~~.~~.~. ~~z:::.·r:;r4~·~~z:::.·~·~~·o-!·~~·~z:::.·r~r~S~·~~z:::.·~·r:;r·o-!~~1r '" '" C\.. '" C\.. C\..-.r '" ~~z:::.·r:;r4~·~~·~~1 ~z:::..(tI.~z:::..a:;~.~~.~.~".~~.~~·o-!z:::.·o-!·u-y~·t.I~·~z:::.·~C4QJl ~'~~~1 ~z:::.'t.Iq·~'*r:;r·~~·t.lq·~r:;r·l~~·~·'1QJ·~i!~~·(tIz:::.l"l·'1:fz:::.'Sz:::.·~1a5.J·~~ ~l~l ~o-!'~l~' ~:~o QJ~' l{.:oo ~~l C\..~ a;~·:uz:::.~1 ~'a:l~' '.l...'.l...lo"I'.l...o'}~ ~l 4~·"r:;r·~QJ·o-!~~1 '" §z:::.·a:;~1 Phone: 322663/325226/325227/323721 Fax: 322992 P.O Box 122 Email: [email protected] Website: www.dzongkha.gov.bt Nicolas Tournadre's Curriculum Vitae Name: Nicolas Toumadre / '",?~.q~"'a:;~.~.q~~. Professor at the University of Aix-Marseille, linguistics department CN~~r~r"'- aI~:~llrmJ::r~ra5~'a,- ~l·~~II ""·qc:rc5~·~~ l~'ifl~"- 'a5~'aII E~ail : [email protected] Professional site: www.nicolas-tournadre.net Education 1984 MA in Russian Literature, Sorbonne University 1987 BA in Tibetan language and civilisation, Institute of Oriental Languages and Civilisation (INalco, Paris) 1989 Louis Forest prize-winning awarded by the "Chancellerie des Universites de Paris". -

The Spiti Valley Recovering the Past & Exploring the Present OXFORD

The Spiti Valley Recovering the Past & Exploring the Present Wolfson College 6 t h -7 t h May, 2016 OXFORD Welcome I am pleased to welcome you to the first International Conference on Spiti, which is being held at the Leonard Wolfson Auditorium on May 6 th and 7 th , 2016. The Spiti Valley is a remote Buddhist enclave in the Indian Himalayas. It is situated on the borders of the Tibetan world with which it shares strong cultural and historical ties. Often under-represented on both domestic and international levels, scholarly research on this subject – all disciplines taken together – has significantly increased over the past decade. The conference aims at bringing together researchers currently engaged in a dialogue with past and present issues pertaining to Spitian culture and society in all its aspects. It is designed to encourage interdisciplinary exchanges in order to explore new avenues and pave the way for future research. There are seven different panels that address the theme of this year’s conference, The Spiti Valley : Recovering the Past and Exploring the Present , from a variety of different disciplinary perspectives including, archaeology, history, linguistics, anthropology, architecture, and art conservation. I look forward to the exchange of ideas and intellectual debates that will develop over these two days. On this year’s edition, we are very pleased to have Professor Deborah Klimburg-Salter from the universities of Vienna and Harvard as our keynote speaker. Professor Klimburg-Salter will give us a keynote lecture entitled Through the black light - new technology opens a window on the 10th century . -

Two Approaches to Non-‐Sectarianism in Twentieth Century Ti

Highlighting Unity: Two Approaches to Non-Sectarianism in Twentieth Century Tibet Adam Pearcey In the late 19th and early 20th centuries there were attempts – apparently connected with the so-called “Ris med Movement” – to strengthen the scholastic traditions of non- dGe lugs schools in Eastern Tibet. These efforts included the establishment of dozens of scriptural colleges (bshad grwa) throughout the region, and the printing and dissemination of works by the Sa skya scholar, Go rams pa bSod nams seng ge (1429– 1489) and the Nyingma polymath, ’Ju Mi pham (1846–1912). The texts of these two influential philosophers, complete with their notorious criticisms of mainstream dGe lugs pa thought, came to represent the orthodox viewpoint for followers of their respective traditions within many newly founded scriptural colleges. These developments were not without controversy, however, and inspired much debate and polemical exchange. In commenting upon this period and its key figures, some modern scholars have questioned how the strengthening and promotion of individual philosophical traditions could be regarded as non-sectarian. Yet, in spite of this, there is no question that ’Ju Mi pham and the publishers of Go rams pa’s writings continue to be associated with the Ris med ideal. In this paper I will explore the views of two writers who took a different approach to inter-sectarian (and intra-sectarian) discourse during this same period of Tibetan history and who both lived in the mGo log region of Eastern Tibet. These authors aimed less at differentiating and strengthening rival doctrines, and more at highlighting their underlying unity or compatibility. -

Buddhism and Medicine in Tibet: Origins, Ethics, and Tradition

Buddhism and Medicine in Tibet: Origins, Ethics, and Tradition William A. McGrath Herndon, Virginia B.Sc., University of Virginia, 2007 M.A., University of Virginia, 2015 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Religious Studies University of Virginia May, 2017 Abstract This dissertation claims that the turn of the fourteenth century marks a previously unrecognized period of intellectual unification and standardization in the Tibetan medical tradition. Prior to this time, approaches to healing in Tibet were fragmented, variegated, and incommensurable—an intellectual environment in which lineages of tantric diviners and scholarly literati came to both influence and compete with the schools of clinical physicians. Careful engagement with recently published manuscripts reveals that centuries of translation, assimilation, and intellectual development culminated in the unification of these lineages in the seminal work of the Tibetan tradition, the Four Tantras, by the end of the thirteenth century. The Drangti family of physicians—having adopted the Four Tantras and its corpus of supplementary literature from the Yutok school—established a curriculum for their dissemination at Sakya monastery, redacting the Four Tantras as a scripture distinct from the Eighteen Partial Branches addenda. Primarily focusing on the literary contributions made by the Drangti family at the Sakya Medical House, the present dissertation demonstrates the process -

Report on the Relationship Between Yolmo and Kagate Journal Issue

Peer Reviewed Title: Report on the relationship between Yolmo and Kagate Journal Issue: Himalayan Linguistics, 12(2) Author: Gawne, Lauren, University of Melbourne Publication Date: 2013 Permalink: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/7vd5d2vm Keywords: Tibeto-Burman, Central Bodic, Yolmo, Kagate, Lexicon Local Identifier: himalayanlinguistics_23716 Abstract: Yolmo and Kagate are two closely related Tibeto-Burman languages of Nepal. This paper provides a general overview of these two languages, including several dialects of Yolmo. Based on existent sources, and my own fieldwork, I present an ethnographic summary of each group of speakers, and the linguistic relationship between their mutually intelligible dialects. I also discuss a set of key differences that have been observed in regards to these languages, including the presence or absence of tone contours, verb stems and honorific lexical items. Although Yolmo and Kagate could be considered dialects of the same language, there are sufficient historical and political motivations for considering them as separate languages. Finally, I look at the status of the "Kyirong-Kagate" sub-branch of Tibetic languages in Tournadre’s (2005) classification, and argue that for reasons discussed in this paper it should instead be referred to as "Kyirong-Yolmo." Copyright Information: Copyright 2013 by the article author(s). This work is made available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs4.0 license, http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ eScholarship provides open access, scholarly publishing services to the University of California and delivers a dynamic research platform to scholars worldwide. Himalayan Linguistics Report on the relationship between Yolmo and Kagate Lauren Gawne The University of Melbourne ABSTRACT Yolmo and Kagate are two closely related Tibeto-Burman languages of Nepal. -

The History of Gyalthang Under Chinese Rule: Memory, Identity, and Contested Control in a Tibetan Region of Northwest Yunnan

THE HISTORY OF GYALTHANG UNDER CHINESE RULE: MEMORY, IDENTITY, AND CONTESTED CONTROL IN A TIBETAN REGION OF NORTHWEST YUNNAN Dá!a Pejchar Mortensen A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Michael Tsin Michelle T. King Ralph A. Litzinger W. Miles Fletcher Donald M. Reid © 2016 Dá!a Pejchar Mortensen ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii! ! ABSTRACT Dá!a Pejchar Mortensen: The History of Gyalthang Under Chinese Rule: Memory, Identity, and Contested Control in a Tibetan Region of Northwest Yunnan (Under the direction of Michael Tsin) This dissertation analyzes how the Chinese Communist Party attempted to politically, economically, and culturally integrate Gyalthang (Zhongdian/Shangri-la), a predominately ethnically Tibetan county in Yunnan Province, into the People’s Republic of China. Drawing from county and prefectural gazetteers, unpublished Party histories of the area, and interviews conducted with Gyalthang residents, this study argues that Tibetans participated in Communist Party campaigns in Gyalthang in the 1950s and 1960s for a variety of ideological, social, and personal reasons. The ways that Tibetans responded to revolutionary activists’ calls for political action shed light on the difficult decisions they made under particularly complex and coercive conditions. Political calculations, revolutionary ideology, youthful enthusiasm, fear, and mob mentality all played roles in motivating Tibetan participants in Mao-era campaigns. The diversity of these Tibetan experiences and the extent of local involvement in state-sponsored attacks on religious leaders and institutions in Gyalthang during the Cultural Revolution have been largely left out of the historiographical record. -

Evidentiality in Tibetic Scott Delancey 1 Introduction the Unusual And

Evidentiality in Tibetic Scott DeLancey 1 Introduction The unusual and unusually prominent grammatical expression of epistemic status and information source in Tibetic languages, especially Lhasa Tibetan,1 has played a prominent role in the study of evidentiality since that category was brought to the attention of the general linguistic public in the early 1980’s. Work by many scholars over the past two decades has produced a substantial body of more deeply-informed research on Lhasa and other Tibetic languages, only a small part of which I will be able to refer to here (see also DeLancey to appear). In this chapter I will mostly discuss Lhasa data, but concentrate on the ways that this system is typical of the pan-Tibetic phenomenon. The system will be presented inductively, in terms of grammatical categories in Tibetic languages, rather than deductively, in terms derived from theoretical claims or typological generalizations about a cross-linguistic category of evidentiality. 1 The terms “Standard” and “Lhasa” Tibetan are sometimes used interchangeably, but they are not exactly the same thing. The early publications on the topic (Goldstein and Nornang 1970, Jin 1979, Chang and Chang 1984, DeLancey 1985, 1986) were based on work with educated speakers from Lhasa, and those works and the data in this paper represent the Lhasa dialect, not “Standard Tibetan”. 2 The first known Tibetic language is Old Tibetan, the language of the Tibetan Empire, recorded in manuscripts from the 7th century CE. In scholarly as well as general use, ‘Tibetan’ is often applied to all descendants of this language, as well as to the written standard which developed from it. -

Epistemic Verbal Endings and Copulas (Preview)

Epistemic Modality in Standard Spoken Tibetan: Epistemic Verbal Endings and Copulas Copulas and Endings Verbal Tibetan: Epistemic Spoken in Standard Modality Epistemic This monograph deals with the grammatical expression of epistemic modalities in standard spoken Tibetan. It describes the system of various types of Epistemic Modality epistemic verbal endings and epistemic copulas frequently employed in the spoken language, as well as those that in Standard occur less frequently. These verbal endings are analyzed from the semantic, syntactic and pragmatic viewpoints, and illustrated by examples. Spoken Tibetan: Epistemic Verbal Endings and Copulas Zuzana Vokurková Zuzana Zuzana Vokurková KAROLINUM epistemic modality_mont.indd 1 29/06/2017 13:53 Epistemic modality in standard spoken tibetan: Epistemic verbal endings and copulas Zuzana Vokurková The original manuscript was peer-reviewed by Nicolas Tournadre, Associate Professor of Linguistics at the University of Paris 8, a member of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (Lacito), and Co-Director of the Tibetan language collection at the Tibetan and Himalayan Digital Library at the University of Virginia; Françoise Robin, Faculty Member, Tibetan department of L’Inalco, l’Université Sorbonne Paris Cité; and Professor Bohumil Palek, Faculty of Arts, Department of Linguistics, Charles University, Prague. Published by Charles University Karolinum Press Layout by Jan Šerých Typeset by Karolinum Press First English edition © Karolinum Press, 2017 © Zuzana Vokurková, 2017 ISBN 978-80-246-3588-0 -

Evidential Systems of Tibetan Languages Trends in Linguistics Studies and Monographs

Lauren Gawne, Nathan W. Hill (Eds.) Evidential Systems of Tibetan Languages Trends in Linguistics Studies and Monographs Editor Volker Gast Editorial Board Walter Bisang Jan Terje Faarlund Hans Henrich Hock Natalia Levshina Heiko Narrog Matthias Schlesewsky Amir Zeldes Niina Ning Zhang Editor responsible for this volume Walter Bisang and Volker Gast Volume 302 Evidential Systems of Tibetan Languages Edited by Lauren Gawne Nathan W. Hill ISBN 978-3-11-046018-6 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-047374-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-047187-8 ISSN 1861-4302 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the internet http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Typesetting: Compuscript Ltd., Shannon, Ireland Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Contents Nathan W. Hill and Lauren Gawne 1 The contribution of Tibetan languages to the study of evidentiality 1 Typology and history Shiho Ebihara 2 Evidentiality of the Tibetan verb snang 41 Lauren Gawne 3 Egophoric evidentiality in Bodish languages 61 Nicolas Tournadre 4 A typological sketch of evidential/epistemic categories in the Tibetic languages 95 Nathan W. Hill 5 Perfect experiential constructions: the inferential semantics of direct evidence 131 Guillaume Oisel 6 On the origin of the Lhasa Tibetan evidentials song and byung 161 Lhasa and Diasporic Tibetan Yasutoshi Yukawa 7 Lhasa Tibetan predicates 187 Nancy J.