Evidentiality and Modality at the Crossroads of Grammar and Lexicon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Steps Toward a Grammar Embedded in Data Nicholas Thieberger

Steps toward a grammar embedded in data Nicholas Thieberger 1. Introduction 1 Inasmuch as a documentary grammar of a language can be characterized – given the formative nature of the discussion of documentary linguistics (cf. Himmelmann 1998, 2008) – part of it has to be based in the relationship of the analysis to the recorded data, both in the process of conducting the analysis with interactive access to primary recordings and in the presenta- tion of the grammar with references to those recordings. This chapter discusses the method developed for building a corpus of recordings and time-aligned transcripts, and embedding the analysis in that data. Given that the art of grammar writing has received detailed treatment in two recent volumes (Payne and Weber 2006, Ameka, Dench, and Evans 2006), this chapter focuses on the methodology we can bring to developing a grammar embedded in data in the course of language documentation, observing what methods are currently available, and how we can envisage a grammar of the future. The process described here creates archival versions of the primary data while allowing the final work to include playable versions of example sen- tences, in keeping with the understanding that it is our professional respon- sibility to provide the data on which our claims are based. In this way we are shifting the authority of the analysis, which traditionally has been lo- cated only in the linguist’s work, and acknowledging that other analyses are possible using new technologies. The approach discussed in this chap- ter has three main benefits: first, it gives a linguist the means to interact instantly with digital versions of the primary data, indexed by transcripts; second, it allows readers of grammars or other analytical works to verify claims made by access to contextualised primary data (and not just the limited set of data usually presented in a grammar); third, it provides an archival form of the data which can be accessed by speakers of the lan- guage. -

The Languages of Amazonia Patience Epps University of Texas at Austin

Tipití: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America Volume 11 Article 1 Issue 1 Volume 11, Issue 1 6-2013 The Languages of Amazonia Patience Epps University of Texas at Austin Andrés Pablo Salanova University of Ottawa Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/tipiti Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Epps, Patience and Salanova, Andrés Pablo (2013). "The Languages of Amazonia," Tipití: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America: Vol. 11: Iss. 1, Article 1, 1-28. Available at: http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/tipiti/vol11/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tipití: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Epps and Salanova: The Languages of Amazonia ARTICLE The Languages of Amazonia Patience Epps University of Texas at Austin Andrés Pablo Salanova University of Ottawa Introduction Amazonia is a linguistic treasure-trove. In this region, defined roughly as the area of the Amazon and Orinoco basins, the diversity of languages is immense, with some 300 indigenous languages corresponding to over 50 distinct ‘genealogical’ units (see Rodrigues 2000) – language families or language isolates for which no relationship to any other has yet been conclusively demonstrated; as distinct, for example, as Japanese and Spanish, or German and Basque (see section 12 below). Yet our knowledge of these languages has long been minimal, so much so that the region was described only a decade ago as a “linguistic black box" (Grinevald 1998:127). -

LACITO - Laboratoire De Langues & Civilisations À Tradition Orale Rapport Hcéres

LACITO - Laboratoire de langues & civilisations à tradition orale Rapport Hcéres To cite this version: Rapport d’évaluation d’une entité de recherche. LACITO - Laboratoire de langues & civilisations à tradition orale. 2018, Université Sorbonne Nouvelle - Paris 3, Centre national de la recherche scien- tifique - CNRS, Institut national des langues et civilisations orientales - INALCO. hceres-02031755 HAL Id: hceres-02031755 https://hal-hceres.archives-ouvertes.fr/hceres-02031755 Submitted on 20 Feb 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Research evaluation REPORT ON THE RESEARCH UNIT: Langues et Civilisations à Tradition Orale LaCiTO UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF THE FOLLOWING INSTITUTIONS AND RESEARCH BODIES: Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3 Institut National des Langues et Civilisations Orientales – INALCO Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique – CNRS EVALUATION CAMPAIGN 2017-2018 GROUP D In the name of Hcéres1 : In the name of the experts committees2 : Michel Cosnard, President Nikolaus P. Himmelmann, Chairman of the committee Under the decree No.2014-1365 dated 14 november 2014, 1 The president of HCERES "countersigns the evaluation reports set up by the experts committees and signed by their chairman." (Article 8, paragraph 5) ; 2 The evaluation reports "are signed by the chairman of the expert committee". -

Colloque International Backing / Base Articulatoire Arrière

Colloque International Backing / Base Articulatoire Arrière du 2 au 4 mai 2012 Lieu/Place : Université Sorbonne Nouvelle - Paris 3, E MAISON DE LA RECHERCHE, 4 RUE DES IRLANDAIS, PARIS 5 (RER B – LUXEMBOURG) Organisateurs : Jean Léo Léonard (LPP, UMR 7018 Paris 3), Samia Naïm (LACITO, UMR 7107, associé à Paris 3), Antonella Gaillard-Corvaglia (LPP, UMR 7018 Paris 3) Pour toute information concernant l’hébergement vous pouvez consulter le site de l’hôtel Senlis : http://www.paris-hotel-senlis.com/ Pourquoi il n'y a pas de pharyngalisation ? Jean-Pierre Angoujard (LLING - Université de Nantes) Si les études sur les consonnes pharyngalisées de l'arabe (les « emphatiques ») ont porté sur la nature de ces consonnes et de l'articulation secondaire qui leur est associée, elles ont plus souvent débattu des effets de coarticulation, c'est-à-dire de la célèbre « diffusion de l'emphase ». A côté de travaux essentiels comme ceux de S. Ghazeli (1977, 1981), la phonologie générative et ses récentes variantes optimales ont suscité de nombreux débats sur cette « diffusion » (types de règles, itération, extension du domaine etc.). L'ensemble de cette littérature sur la « diffusion de l'emphase » (et spécifiquement l'interprétation du terme « pharyngalisation ») a souffert d'une confusion entre, d'une part la reconnaissance des effets de coarticulation et, d'autre part, les descriptions par règles de réécriture ou par contraintes de propagation (spread). Nous montrerons, dans un cadre purement déclaratif (Bird 1995, Angoujard 2006), que la présence de segments pharyngalisés (que l'on peut désigner, pour simplifier, comme non « lexicaux ») n'implique aucun processus modificateur (insertion, réécriture). -

CURRICULUM VITAE Alexandra Yurievna Aikhenvald

ALEXANDRA Y. AIKHENVALD CURRICULUM VITAE Current address: work: home: The Cairns Institute 21 Anne Street, James Cook University Smithfield, Cairns, Qld 4870 Qld 4878 Australia e-mail: [email protected] [email protected] phone: 61-(0)7-4240117 (work); 0400 305315 Citizenship: Australian Educated • Department of Structural and Applied Linguistics, Philological Faculty, Moscow State University: BA in Linguistics 1978; MA in Linguistics 1979 (thesis topic: 'Relative Clause in Anatolian Languages') • Institute of Oriental Studies of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, Moscow: PhD in Linguistics, 1984 (thesis topic 'Structural and Typological Classification of Berber Languages') • La Trobe University, 2006: Doctor of Letters by examination of four books and 14 papers. Positions held • Research Fellow, Department of Linguistics, Institute of Oriental Studies of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, January 1980 - September 1988 • Senior Research Fellow, ibidem, September 1988 - July 1989 • Visiting Professor, Federal University of Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, Brazil, August 1989 - December 1991 • Associate Professor, ibidem, December 1991 - December 1992 • Full Professor with tenure, ibidem, December 1992 - February 1994 • Visiting Professor, State University of Campinas, Brazil, April 1992 - June 1992 • Visiting Professor, University of São Paulo, Brazil, July 1992 - December 1992 • Visiting Fellow, Australian National University, January - February 1993 • ARC Senior Research Fellow (with rank of Professor), Australian National University, February 1994 - 1999, Second Term: February 1999 - 2004 • Professor of Linguistics, Research Centre for Linguistic Typology, La Trobe University, from 2004 - 2008 • Associate Director of the Research Centre for Linguistic Typology, Australian National University, 1996-1999 • Associate Director of the Research Centre for Linguistic Typology, La Trobe University, 2000-2008 • Professor and Research Leader (People and Societies of the Tropics), Cairns Institute, James Cook University, 2009-present. -

Frustrations of the Documentary Linguist: the State of the Art in Digital Language Archiving and the Archive That Wasnâ•Žt

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Department of Spanish Research Spanish 2006 Frustrations of the Documentary Linguist: The State of the Art in Digital Language Archiving and the Archive that Wasn’t Robert E. Vann [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/spanish_research Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons WMU ScholarWorks Citation Vann, Robert E., "Frustrations of the Documentary Linguist: The State of the Art in Digital Language Archiving and the Archive that Wasn’t" (2006). Department of Spanish Research. 1. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/spanish_research/1 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Spanish at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Department of Spanish Research by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Frustrations of the documentary linguist: The state of the art in digital language archiving and the archive that wasn’t Robert E. Vann Western Michigan University 1.0 Introduction This paper is a qualitative review and critique of existing electronic language archives from the perspective of the documentary linguist. In today’s day and age there are many online archives available for storage of and access to digital language data, among others: AILLA, ANLC, ASEDA, DOBES, ELRA, E-MELD, LACITO, LDC, LPCA, OTA, PARADISEC, Rosetta, SAA, THDL, and UHLCS. It is worth pointing out that I use the term language archive loosely in this paper, referring to a variety of organizations and resources such as those listed above that store and provide digital language data to different degrees and for different purposes. -

PPD Talk by Prof. Nicolas Tournadre

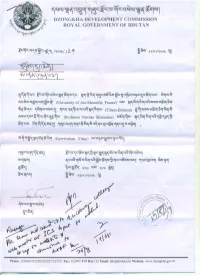

-. '" ~~Q.l·~~·q~~·~~~·~,,·rq·~,,·qt4Q.l·~~·l~~l DZONGKHA DEVELOPMENT COMMISSION ROYAL GOVERNMENT OF BHUTAN "'~=<~r\"~\"\~T"""""'" ..~ D. oN' qJ{, n..,~~V){"\ ..."."" ~ t ,. '" '" '" -.r '" 7::F. '" C\.. '" C\.. '" C\ '" '" '" ~.~~.~.u-yz:::..~z:::..(tI.~z:::..~t4QJ.~~.ct:l~~.~z:::~~·~·"~·~~z:::.·o-!sa·,,o-!·~z::r:Ir~~~·o-!~o-!·~r:;r·sa~·QJ~·.~~~.~.. ~".~QJ.~~~.QJ~.~r:;r.~. (University of Aix-Marseille, France) QJ~' ~~.~~.~~.t.lq.o-!(tI~.~~~.~~. C\..C\.. C\.. C\.. C\.. C\.. C\.. ",C\C\..C\.. ~~'~'~z:::.' ~~~~'r:;r~QJ'~' ~z:::.~·-o~·7·o-!·QJ·u-y~·~~·,,~~·(Tibeto-Bunnan) ~.~.~(tI~.~a:;~.-o~.~~.o-!. C\..-.r '" C\.. '" C\.. C\.. C\.. C\.. '" C\.. ~(tI~.~r:;rz:::..~."l.QJ.~".~~.~~.(Professor Nicolas 'J:oumadre) o-!a:;~'~~' ~~·u-y~·,,~·t.I~·~S·~~~·~· '" '" C\..'" C\..C\.. C\.. C\ '" '" sa~'QJ~' ~~.~.~~.~~.~. ~~z:::.·r:;r4~·~~z:::.·~·~~·o-!·~~·~z:::.·r~r~S~·~~z:::.·~·r:;r·o-!~~1r '" '" C\.. '" C\.. C\..-.r '" ~~z:::.·r:;r4~·~~·~~1 ~z:::..(tI.~z:::..a:;~.~~.~.~".~~.~~·o-!z:::.·o-!·u-y~·t.I~·~z:::.·~C4QJl ~'~~~1 ~z:::.'t.Iq·~'*r:;r·~~·t.lq·~r:;r·l~~·~·'1QJ·~i!~~·(tIz:::.l"l·'1:fz:::.'Sz:::.·~1a5.J·~~ ~l~l ~o-!'~l~' ~:~o QJ~' l{.:oo ~~l C\..~ a;~·:uz:::.~1 ~'a:l~' '.l...'.l...lo"I'.l...o'}~ ~l 4~·"r:;r·~QJ·o-!~~1 '" §z:::.·a:;~1 Phone: 322663/325226/325227/323721 Fax: 322992 P.O Box 122 Email: [email protected] Website: www.dzongkha.gov.bt Nicolas Tournadre's Curriculum Vitae Name: Nicolas Toumadre / '",?~.q~"'a:;~.~.q~~. Professor at the University of Aix-Marseille, linguistics department CN~~r~r"'- aI~:~llrmJ::r~ra5~'a,- ~l·~~II ""·qc:rc5~·~~ l~'ifl~"- 'a5~'aII E~ail : [email protected] Professional site: www.nicolas-tournadre.net Education 1984 MA in Russian Literature, Sorbonne University 1987 BA in Tibetan language and civilisation, Institute of Oriental Languages and Civilisation (INalco, Paris) 1989 Louis Forest prize-winning awarded by the "Chancellerie des Universites de Paris". -

Martin Haspelmath, List of Publications

Martin Haspelmath - List of publications To appear 2010: [Andrej L. Malchukov, Martin Haspelmath & Bernard Comrie] 2010. Studies in Ditransitive Constructions: A Comparative Handbook. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. "The Behaviour-before-Coding Principle in syntactic change." To appear in: Floricic, Franck (ed.) Mélanges Denis Creissels. Paris: Presses de L'École Normale Supérieure. [Uri Tadmor, Martin Haspelmath & Bradley Taylor] "Borrowability and the notion of basic vocabulary." Diachronica 2010 "Framework-free grammatical theory." In: Heine, Bernd & Narrog, Heiko (eds.) The Oxford handbook of grammatical analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 341-365. 2009 [Martin Haspelmath & Uri Tadmor] (eds.) 2009. Loanwords in the World's Languages: A Comparative Handbook. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, 1081 pp. [Martin Haspelmath & Uri Tadmor] (eds.) 2009. World Loanword Database. Munich: Max Planck Digital Library. Online resource, <http://wold.livingsources.org/> [Martin Haspelmath & Uri Tadmor]. 2009. "The Loanword Typology project and the World Loanword Database." In: [Martin Haspelmath & Uri Tadmor] (eds.) 2009. Loanwords in the World's Languages: A Comparative Handbook. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, 1-34. "Lexical borrowing: Concepts and issues." In: Martin Haspelmath & Uri Tadmor (eds.) 2009. Loanwords in the World's Languages: A Comparative Handbook. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, 35-54. "Terminology of case." In: Malchukov, Andrej & Spencer, Andrew (eds.) 2009. The Oxford handbook of case. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 505-517. "An empirical test of the Agglutination Hypothesis." Scalise, Sergio & Magni, Elisabetta & Bisetto, Antonietta (eds.) 2009. Universals of language today. (Studies in Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 76.) Dordrecht: Springer, 13-29. "The typological database of the World Atlas of Language Structures." In: Everaert, Martin & Musgrave, Simon (eds.) 2009. -

Buddhism and Medicine in Tibet: Origins, Ethics, and Tradition

Buddhism and Medicine in Tibet: Origins, Ethics, and Tradition William A. McGrath Herndon, Virginia B.Sc., University of Virginia, 2007 M.A., University of Virginia, 2015 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Religious Studies University of Virginia May, 2017 Abstract This dissertation claims that the turn of the fourteenth century marks a previously unrecognized period of intellectual unification and standardization in the Tibetan medical tradition. Prior to this time, approaches to healing in Tibet were fragmented, variegated, and incommensurable—an intellectual environment in which lineages of tantric diviners and scholarly literati came to both influence and compete with the schools of clinical physicians. Careful engagement with recently published manuscripts reveals that centuries of translation, assimilation, and intellectual development culminated in the unification of these lineages in the seminal work of the Tibetan tradition, the Four Tantras, by the end of the thirteenth century. The Drangti family of physicians—having adopted the Four Tantras and its corpus of supplementary literature from the Yutok school—established a curriculum for their dissemination at Sakya monastery, redacting the Four Tantras as a scripture distinct from the Eighteen Partial Branches addenda. Primarily focusing on the literary contributions made by the Drangti family at the Sakya Medical House, the present dissertation demonstrates the process -

Sociolinguistic Situation of Kurdish in Turkey: Sociopolitical Factors and Language Use Patterns

DOI 10.1515/ijsl-2012-0053 IJSL 2012; 217: 151 – 180 Ergin Öpengin Sociolinguistic situation of Kurdish in Turkey: Sociopolitical factors and language use patterns Abstract: This article aims at exploring the minority status of Kurdish language in Turkey. It asks two main questions: (1) In what ways have state policies and socio- historical conditions influenced the evolution of linguistic behavior of Kurdish speakers? (2) What are the mechanisms through which language maintenance versus language shift tendencies operate in the speech community? The article discusses the objective dimensions of the language situation in the Kurdish re- gion of Turkey. It then presents an account of daily language practices and perceptions of Kurdish speakers. It shows that language use and choice are sig- nificantly related to variables such as age, gender, education level, rural versus urban dwelling and the overall socio-cultural and political contexts of such uses and choices. The article further indicates that although the general tendency is to follow the functional separation of languages, the language situation in this con- text is not an example of stable diglossia, as Turkish exerts its increasing pres- ence in low domains whereas Kurdish, by contrast, has started to infringe into high domains like media and institutions. The article concludes that the preva- lent community bilingualism evolves to the detriment of Kurdish, leading to a shift-oriented linguistic situation for Kurdish. Keywords: Kurdish; Turkey; diglossia; language maintenance; language shift Ergin Öpengin: Lacito CNRS, Université Paris III & Bamberg University. E-mail: [email protected] 1 Introduction Kurdish in Turkey is the language of a large population of about 15–20 million speakers. -

Ssila Bulletin

The Society for the Study of the Indigenous Languages of the Americas SSILA BULLETIN An Information Service for SSILA Members Editor - Victor Golla ([email protected]) Associate Editor - Scott DeLancey ([email protected]) Correspondence should be directed to the Editor Number 73: September 16, 1998 73.1 CORRESPONDENCE Books for sale · From Frances Karttunen ([email protected]) 15 Sept 1998: Louise Dale has sent me a list of books (but without prices) from her husband's library that she is offering for sale (SSILA Bulletin #71.1, August 21, 1998). Titles of potential interest to SSILA members include the following: § Benevente, Toribio de (Motolinia). 1914 ed. Historia de los indios de la nueva espana. § Molina, Alonso de. 1880 ed. Vocabulario de la lengua mexicana. § Gonzalez, Rufino. 1913. Aztec grammar and dictionary. § Bennett, Wendell C., and Robert Zingg. 1935. The Tarahumara: An Indian Tribe of Northern Mexico. § Bingham, Hiram. 1948. The Lost City of the Incas. § Prescott, William. 1843. History of the Conquest of Mexico. Col. II. § Radin, Paul. 1937. The Story of the American Indian. § Nida, Eugene. 1974. Understanding Latin Americans. § Coe, Michael. 1962. America's First Civilization: Discovering the Olmec. § Lewis, Oscar. 1963. Life in a Mexican Village: Tepoztlan Restudied. § Garibay K., Angel Maria. 1954. Historia de la literatura nahuatl. § Leon-Portilla, Miguel. 1963. Aztec Thought and Culture. § Codex Fejervart-Mayor. The Liverpool City Museum. Published in Oxford, UK. § Codex Nuttall, edited by Zelia Nuttall. § Codex Laud. The Bodlean Library, Oxford, UK. § Codex Borgia with commentary. The Vatican Library, Rome. § Paso y Troncoso, Francisco del. 1898. -

Epistemic Verbal Endings and Copulas (Preview)

Epistemic Modality in Standard Spoken Tibetan: Epistemic Verbal Endings and Copulas Copulas and Endings Verbal Tibetan: Epistemic Spoken in Standard Modality Epistemic This monograph deals with the grammatical expression of epistemic modalities in standard spoken Tibetan. It describes the system of various types of Epistemic Modality epistemic verbal endings and epistemic copulas frequently employed in the spoken language, as well as those that in Standard occur less frequently. These verbal endings are analyzed from the semantic, syntactic and pragmatic viewpoints, and illustrated by examples. Spoken Tibetan: Epistemic Verbal Endings and Copulas Zuzana Vokurková Zuzana Zuzana Vokurková KAROLINUM epistemic modality_mont.indd 1 29/06/2017 13:53 Epistemic modality in standard spoken tibetan: Epistemic verbal endings and copulas Zuzana Vokurková The original manuscript was peer-reviewed by Nicolas Tournadre, Associate Professor of Linguistics at the University of Paris 8, a member of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (Lacito), and Co-Director of the Tibetan language collection at the Tibetan and Himalayan Digital Library at the University of Virginia; Françoise Robin, Faculty Member, Tibetan department of L’Inalco, l’Université Sorbonne Paris Cité; and Professor Bohumil Palek, Faculty of Arts, Department of Linguistics, Charles University, Prague. Published by Charles University Karolinum Press Layout by Jan Šerých Typeset by Karolinum Press First English edition © Karolinum Press, 2017 © Zuzana Vokurková, 2017 ISBN 978-80-246-3588-0