Incentives, Technology and the Shift to Year-Round Dairying in Late 19Th Century Denmark

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Odense Rutekort 2014

140 Odense Odense 190 Søndersø 91 Allesø Lumby 92 141 Otterup 191 Bogense Søhusvej Kirkegyden Næsbyhoved 61 Stige Hedelundvej Seden Broby Ande rupvej Strandby Bogensevej 151 152 Kerteminde Kirkendrup Slettensvej Stavadgyden n Kertemindevej Kirkendrupvej ispeenge 51 11 Søhus B Agedrup 23 Morud Brolandvej n e lu Stærehusvej K setv Odense kanal k ej Seden Kertemindevej 122 Morud / Søndersø / Hårslev k a b e 28 d Lunden e 71 72 m 71 81 82 83 Bullerupvej 22 Slukefter Korup 29 S Skibhusene 52 Bullerup Villestofte Otterupvej Søgårdsvej Ejbygade olmvej Rugårdsvej Næsby Sprogø- h Snestrup Højvang Fridas Bogensevej vej Rismarksvej Kertemindevej Skibhus- Seden Syd u Hybenhaven L mb skoven Rugårdsvej yv Fuglebakken e Sandhusvej j 31 32 Ørnevej Fredens Birkeparken Næsbyvej S Ejbygade Skolevej v Pårup Kirke e Næsbyhoved n Spangsvej Tarupvej d Tyrsbjergvej s Skov j Døckerslundsvej a Bøgeparken V e o g Tarup v e Kochsgade l r H s l v s e Center u j j a m e Lunden v h v l Vollsmose o Tarup b n i s e k Pårupvej e na Rugårdsvej g Egeparken S Damhusvej a a A d K l Jernbanevej l e Åløkke Risingsvej é E Center Øst j ls t ru pvej Kalørvej Ejlstrup Åsumvej Ringvej Østre Rismarksvej H AlléÅløkke Åsum Bygade ø Østerbro js Åsum tr Odense Åsumvej Pårupvej u pv Rugårdsvej ej Stadion j Se ve e Rågelundvej Højstrup n Bymidte- Gad Munkerudgyden io ns d kort Frederiks- Skt. Jørge ta gade Højemarksvej S 31 Ejbygade Ubberud Staupudevej 21 Vestre Stationsvej Nyborgvej Stegsted Middelfartvej 885 Kerteminde Albani- Nyborgvej Vesterbro gade Munkebjergvej Korsløkke Middelfartvej Ørbækvej Nyborgvej Allégade Røde- Ansgar gårdsvej Anlæg Blommenslyst Heden Kløvermosevej Ka Nyborgvej st Falen anie L.A.Rings Herluf Trolles Vej 130 Vissenbjerg / Assens vej vej Munkerisvej 91 92 31 Bolbro 131 Vissenbjerg / Haarby Kragsbjerg Herluf Trolles Vej Hjallesevej 190 Langeskov Friluftsbad OUH Hunderup RødegårdsvejRosengård- Olfert Sdr. -

M/S Museets for Søfart Årbog 2012

SLÆGTSFORSKERNES BIBLIOTEK Dette værk er downloadet fra Slægtsforskernes Bibliotek Slægtsforskernes Bibliotek drives af foreningen Danske Slægtsforskere. Det er et privat special-bibliotek med værker, der er en del af vores fælles kulturarv omfattende slægts-, lokal- og personalhistorie. Støt Slægtsforskernes Bibliotek - Bliv sponsor Som sponsor i biblioteket opnår du en række fordele. Læs mere om fordele og sponsorat her: https://www.dsshop.dk/sponsorat Ophavsret Biblioteket indeholder værker både med og uden ophavsret. For værker, som er omfattet af ophavsret, må PDF-filen kun benyttes til personligt brug. Videre publicering og distribution uden for husstanden er ulovlig. Links Slægtsforskernes Bibliotek: https://bibliotek.dis-danmark.dk Danske Slægtsforskere: https://slaegt.dk Museet for Søfart Maritime Museum of Denmark ÅRBOG 2012 UDGIVET AF M/S MUSEET FOR SØFARTS VENNER M/S MUSEET FOR SØFARTS ÅRBOG Register til årbøgerne 1942-61 findes i årbog 1961, 2012-udgaven er bind 71 i rækken af museets årbøger til 1962-66 i årbog 1966, © M/S Museet for Søfart til 1967-71 i årbog 1971, til 1972-76 i årbog 1976, Redaktion: Jørgen Selmer og Benjamin Asmussen til 1977-81 i årbog 1982, Oversættelser: Charlotte Lindhardt, forfatterne og til 1982-86 i årbog 1986, redaktionen til 1987-91 i årbog 1991, til 1992-96 i årbog 1997, ISBN 978-87-7015-006-4 til 1997-01 i årbog 2002, ISSN 0085-1418 til 2002-06 i årbog 2007, til 2007-11 i denne årbog. Grafisk formgivning: Peter Dyrvig Grafisk Design Bogen er sat med Myriad Pro og ITC Laurel Årbøgerne 1942-2008 er frit tilgængelige på Trykt hos Zeuner Grafisk museets hjemmeside. -

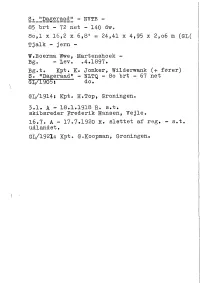

85 Brt - 72 Net - 140 Dw

S^o^^Dageraad*^ - WVTB - 85 brt - 72 net - 140 dw. 8o,l x 16,2 x 6,8' = 24,41 x 4,95 x 2,o6 m (GL( Tjalk - jern - W.Boerma Wwe, Martenshoek - Bg. - lev. .4.1897. Bg.t. Kpt. Ko Jonker, Wilderwank (+ fører) S. "Dageraad" - NLTQ - 8o brt - 67 net GI/1905: do. GL/1914: KptO H.Top, Groningen. 3.1. A - 18.1.1918 R. s.t. skibsreder Frederik Hansen, Vejle, 16.7. A - 17.7.1920 R. slettet af reg. - s.t. udlandet. Gl/1921: Kpt. G.Koopman, Groningen. ^Dagmar^ - HBKN - , 187,81 hrt - 181/173 NRT - E.C. Christiansen, Flenshurg - 1856, omhg. Marstal 1871. ex "Alma" af Marstal - Flb.l876$ C.C.Black, Marstal. 17.2.1896: s.t. Island - SDagmarS - NLJV - 292,99 brt - 282 net - lo2,9 x 26,1 x 14,1 (KM) Bark/Brig - eg og fyr - 1 dæk - hækbg. med fladt spejl - middelf. bov med glat stævn. Bg. Fiume - 1848 - BV/1874: G. Mariani & Co., Fiume: "Fidente" - 297 R.T. 29.8.1873 anrn. s.t. partrederi, Nyborg - "DagmarS - Frcs. 4o.5oo mægler Hans Friis (Møller) - BR 4/24, konsul H.W. Clausen - BR fra 1875 6/24 købm. CF. Sørensen 4/24 " Martin Jensen 4/24 skf. C.J. Bøye 3/24 skf. B.A. Børresen - alle Nyborg - 3/24 29.12.1879: Forlist p.r. North Shields - Tuborg havn med kul - Sunket i Kattegat ca. 6 mil SV for Kråkan, da skibet ramtes af brådsø, der knækkede alle støtter, ramponerede skibets ene side, knuste båden og ødelagde pumperne. -

You Drive, We Care

You drive, we care. DK - Diesel & Services Dänemark / Danmark / Denmark PLZ sortiert Sorted by ZIP code » For help, call me! DKV ASSIST - 24h International Free Call* 00800 365 24 365 In case of difficulties concerning the number 00800 please dial the relevant emergency number of the country: Bei unerwarteten Schwierigkeiten mit der Rufnummer 00800, wählen Sie bitte die Notrufnummer des Landes: Andorra / Andorra Latvia / Lettland » +34 934 6311 81 » +370 5249 1109 Austria / Österreich Liechtenstein / Liechtenstein » +43 362 2723 03 » +39 047 2275 160 Belarus / Weißrussland Lithuania / Litauen » 8 820 0071 0365 (national) » +370 5249 1109 » +7 495 1815 306 Luxembourg / Luxemburg Belgium / Belgien » +32 112 5221 1 » +32 112 5221 1 North Macedonia / Nordmazedonien Bosnia-Herzegovina / Bosnien-Herzegowina » +386 2616 5826 » +386 2616 5826 Moldova / Moldawien Bulgaria / Bulgarien » +386 2616 5826 » +359 2804 3805 Montenegro / Montenegro Croatia / Kroatien » +386 2616 5826 » +386 2616 5826 Netherlands / Niederlande Czech Republic / Tschechische Republik » +49 221 8277 9234 » +420 2215 8665 5 Norway / Norwegen Denmark / Dänemark » +47 221 0170 0 » +45 757 2774 0 Poland / Polen Estonia / Estland » +48 618 3198 82 » +370 5249 1109 Portugal / Portugal Finland / Finnland » +34 934 6311 81 » +358 9622 2631 Romania / Rumänien France / Frankreich » +40 264 2079 24 » +33 130 5256 91 Russia / Russland Germany / Deutschland » 8 800 7070 365 (national) » +49 221 8277 564 » +7 495 1815 306 Great Britain / Großbritannien Serbia / Serbien » 0 800 1975 520 -

Danske Skibe I Tysk Malmfart^ Under 2. Verdenskrig

Ole Stig Johannesen: rVialmfarten - danske skibe i tysk malmfart^ under 2. verdenskrig Forfatteren er lektor cand. mag. i fransk, tysk og lænderne nedkastede store mængder af russisk, men har også en maritim fortid. Han miner i håb om at spærre for gennemsej har desuden skrevet bøger om rederierne ØK, Ove lingen i Øresund og Bælterne. En tysk Skou, Dansk-Fransk ogA.P. Møller-Mærsk. Der minespærring blev lagt tværs over Skager er aldrig før foretaget en undersøgelse i Fragt rak fra Danmark til Norge, så at ingen bri nævnets arkiv2> med henblik på at finde frem til tiske krigsskibe kunne dukke op i de dan skibene i den pågældende malmfart. Såvel antal ske farvande - og de danske handelsfar- let af skibe som omfanget af den transporterede tøjer kunne heller ikke slippe ud. De gen mængde af jernmalm virker overraskende. sidige mineringer omfattede både hornmi nerne, der eksploderede ved kontakt med De generelle forhold for skibsfarten skibet samt de mere udspekulerede mag i de danske farvande netiske miner, der kunne indstilles, så at Med den tyske besættelse af Danmark i der skulle et vist antal oversejlinger til, før april 1940 blev handelsflåden som bekendt de udløstes. Der blev foretaget minestryg delt op i den del, der var i udenrigsfart og ninger, og al sejlads foregik i disse tvangs således uden for Tysklands rækkevidde og i ruter, der kun var nødtørftigt afmærkede. den del, der befandt sig i de hjemlige Havnefogeden udleverede sejladsanvisnin farvande og som følge heraf blev underlagt ger til skibets kaptajn umiddelbart før ski tyske krav. Det var ca. -

Munkebjerg Businesspark

Munkebjerg Business Park VELKOMMEN I 2020 TIL NYKREDIT OG PwC 3.253 M² ER UDLEJET LEJEPROSPEKT Eksklusivt kontorhus til ambitiøse lejere opføres nu på bedste beliggenhed i Odense Barfoed Group udvikler et 125.000 m² stort grundareal på hjørnet af Niels Bohrs Alle og Munkebjergvej, med fokus på kvalitet, bæredygtighed og funktionalitet. Med en bebyggelsesprocent på blot 60 er der god plads til Munkebjerg Business Park ud mod indfaldsvejene, og til Munkebjerg Parks eksklusive boliger til alle aldersgrupper. Barfoed Group er en af Danmarks største private ejendomsbesiddere og koncernen råder i dag over mere end 3.500 lejemål med ligelig fordeling på bolig og erhverv. Koncernens styrke er blandt andet kendetegnet ved en professionel og moderne ejendomsadministration, bestående af dygtige og engagerede medarbejdere i både administrationen, økonomiafdelingen og den tekniske afdeling, herunder egen entreprenørafdeling, som vedligeholder og udvikler ejendomsporteføljen. Hos Barfoed Group er lejerne således altid i trygge hænder, og vi ser frem til at byde flere gode lejere velkommen i Munkebjerg Business Park. 2 H Ny bydel på 73.000 m² A 5.300 m² kontorhus opføres nu. PwC og Nykredit F flytter ind medio 2020, og der er plads til 1-2 gode virksomheder mere A B 1.200 m² dagligvareforretning opføres nu. D Udlejet til Lidl C 13.500 m² boliger i høj kvalitet opføres nu. Skriv til [email protected] for information om boliglejemål, som forventes klar ultimo 2019. D 500 m² konferencebygning med køkken, toiletter E og moderne AV-udstyr B E 11.000 m² eksisterende boligbyggeri F 8.000 m² kommende byggeri til kontor, hotel, fitness, restaurant m.m. -

Årsrapport 2012 Og Miljøforhold

Årsrapport 2012 og miljøforhold CVR-nr. 30 17 49 68 Fjernvarme er miljøvenlig www.fjernvarmefyn.dk Indholdsfortegnelse Selskabsoplysninger 3 Ledelsespåtegning 4 Den uafhængige revisors erklæringer 5 Ledelsesberetning 6 Anvendt regnskabspraksis 15 Resultatopgørelse for 2012 19 Balance pr. 31.12.2012 20 Egenkapitalopgørelse for 2012 23 Pengestrømsopgørelse for 2012 24 Noter 25 Miljøforhold 33 Ressourceopgørelse 35 2 Selskabsoplysninger Selskab Bestyrelse Direktion Fjernvarme Fyn A/S Michael Bruhn Frederiksen, formand Jan Strømvig Billedskærervej 7 Lars Chr. Lilleholt, næstformand 5230 Odense M Christian Skov Frederiksen CVR-nr.: 30 17 49 68 Kim Jørgen Jensby Jørgensen Revision Hjemstedskommune: Odense Line Mørk Deloitte Statsautoriseret Revisionspartnersel- Stiftet 20.12.2006 Helge Pasfall skab Regnskabsår 01.01.-31.12. Flemming Hintze Jensen, medarbejdervalgt Telefon: 65 47 30 00 Jakob Storm Rasmussen, medarbejdervalgt Godkendt på selskabets generalforsamling, Telefax: 65 47 30 01 Jan Thrane Sørensen, medarbejdervalgt Odense den 8. maj 2013. Internet: www.fjernvarmefyn.dk E-mail: [email protected] Dirigent 3 Ledelsespåtegning Bestyrelsen og direktionen har dags dato behandlet og godkendt årsrapporten for regn- skabsåret 1. januar - 31. december 2012 for Fjernvarme Fyn A/S. Årsrapporten aflægges i overensstemmelse med årsregnskabsloven, tilpasset de regler, der følger af lov om varmeforsyning og Energiministeriets bekendtgørelse nr. 175 af 18. marts 1991 om afskrivninger og henlæggelser m.v. Det er vores opfattelse, at årsregnskabet giver et retvisende billede af selskabets aktiver, passi- ver og finansielle stilling pr. 31. december 2012 samt af resultatet af selskabets aktiviteter og pengestrømme for regnskabsåret 1. januar - 31. december 2012. Ledelsesberetningen indeholder efter vores opfattelse en retvisende redegørelse for de forhold, beretningen omhandler. Årsrapporten indstilles til generalforsamlingens godkendelse. -

Folketingsvalget Den 22. September 1953

DANMARKS STATISTIK STATISTISKE MEDDELELSER 4. REKKE 155. BIND 1. HEFTE FOLKETINGSVALGET DEN 22. SEPTEMBER 1953 ELECTIONS TO THE FOLKETING SEPTEMBER 22, 1953 UDGIVET AF DET STATISTISKE DEPARTEMENT PUBLISHED BY THE STATISTICAL DEPARTMENT KOBENHAVN BIANCO LUNOS BOGTRYKKERI 1954 Tidligere udgivne publikationer vedrerende rigsdagsvalg. Valgene til den grundlovgiv. Rigsd. Stat. Tabelværk, Ældste rk. 17. h. Folketingsvalgene 1849. 32 22 Ny rk. 2. bd. 22 1852 og 1853. 9. 1854, 1855, 1858 og 1861. Stat. Medd., 2. rk. 1. bd. 4. h. ,, 1869, 1872 og 1873. ,, 2. rk. 12. bd. 3. h. 22 1876 og 1879. 25 3. rk. 3. bd. 2. h. ,, 1881 og 1884. ,, ,, 3. rk. 8. bd. 1. h. 22 1887, 1890 og 1892. 75 3. rk. 13. bd. 1. h. 22 1895 og 1898. 12 ., 4. rk. 3. bd. 4. h. 1901. ,, ,, 4. rk. 10. bd. 2. h. 1903. 4. rk. 13. bd. 6. h. 23 1906. 32 4. rk. 22. bd. 1. h. 52 1909. 52 22 4. rk. 31. bd. 6. h. 1910. 4. rk. 35. bd. 2. h. ,, 1913. ,, ,, 4. rk. 42. bd. 3. h. 1915. ,, ,, 4. rk. 48. bd. 1. h. Rigsdagsvalgene 1918. ,, 4. rk. 57. bd. 1. h. Folketingsvalget aprii 1920. 32 4. rk. 60. bd. 3. h. Rigsdagsvalgene juli-august 1920. 22 4. rk. 61. bd. 1. h. Folkeafstemningen 1920. Stat. Efterretn. 1920, nr. 23. Rigsdagsvalgene sept.-okt. 1920. Stat. Medd., 4. rk. 62. bd. 1. h. Folketingsvalget 1924. ,, ,, 4. rk. 71. bd. 1. b. Landstingsvalget 1924. ,, 4. rk. 71. bd. 3. h Folketingsvalget 1926. ,, 4. rk. 77. bd. 1. h Landstingsvalget 1928. -

Supersygehus for Hele Regionen Fælles Akutmodtagelse Vil Redde Flere Liv Patienter Behandles Via Internettet 08 Ouhfør,Nu Og I Fremtiden

14. - 15. APRIL 2012 JydskeVestkysten Vejle Amts Folkeblad Fredericia Dagblad Fyns Amts Avis OUH Fyens Stiftstidende 100 Supersygehus for hele regionen Fælles Akutmodtagelse vil redde flere liv Patienter behandles via internettet 08 OUHfør,nu og i fremtiden 1912 kunne Odense tilbyde det nyeste og mest moderne sygehus i provinsen. Bygget og indrettet med det kun to år ældre Rigshospitalet som forbillede. II 2021 kan Odense tilbyde det nyeste og mest mo- derne supersygehus i Danmark. Bygget og indrettet med ny teknologi, som på nuværende tidspunkt be- finder sig på et forsøgsstadium. Men indtil da er der god grund til at markere den indsats og udvikling, som Odense Universitetsho- spital har leveret i 100 år. Med en kapacitet og lægefaglige specialer, der rækker ud over de regionale grænser. Indhold Forgodtnokvar det et sygehus for Odense By og Amt, der blev taget i brug for 100 år siden. Og byg- ningerne står der endnu, selv om de er klemt inde af Artikler flere årtiers nybyggeri. For trods Men det er som universitets- Syge børn har brug for trygge rammer 4-5 hospital og flagskib i Region avanceret Syddanmarks sundhedsvæsen, Helt styr på hjertet 8-10 teknologi at OUH har en førende posi- tion og fremtid i det danske Ny akutmodtagelse vil redde flere liv 12-14 handler sundhedsvæsen. hverdagen på Minutterne tæller på det nye traumecenter 16-18 Et 100-års jubilæum i en stor Uden mad og drikke duer patienten ikke 20-22 et stort hospital virksomhed er en naturlig an- også om alle de ledning til både at kigge tilbage Et stort skridt ind i fremtiden 26-27 og frem i tiden. -

Aarhus Storborgerslægter.Pdf

Kilde J. Hoffmeyer: "Blade af Aarhus Byes Historie". I. (2. Halvbind, 1906) Aarhusianske Storborgerslægter i Slutningen af 17. Aarhundrede. I Begyndelsen af det syttende Aarhundrede levede der i Aarhus en højt anset Læge ved Navn Mathias (Mads) Jacobsen eller Jacobæus, Phil. Med. Doctor f. 1570. Han var Søn af en Biskop i Odense, Jacob Madsen, (Vejle), havde i sine yngre Dage rejst i Tyskland, Sicilien, Frankrig og England, samt indtaget en fremragende Stilling som Lærd i Padua. I Aaret 1614 udnævntes han til Livlæge hos Kong Christian IV, men tog sin Afsked fra Hoffet, og da han hørte til en gammel Aarhusslægt, bosatte han sig i Aarhus og blev gift med Ingeborg Johanne (d. 1620) en Datter af Biskop Jens Giødesen (Janus Ægidius (d. 1626).1 I Aarhus levede han Størstedelen af sit Liv som Prælat i Domkapitlet og boede vistnok i en Kannikegaard, som har ligget i Kannikegade, der hvor Grosserer Schourups Gaard nu ligger. Forresten nævnes han ogsaa som Ejer af enkelte an- dre Grunde i Aarhus. At en Læge var Medlem af Domkapitlet var i hine Tider ingen Sjældenhed, baade Doct. med. Jacob Fabricius og Doct. med. Simon Paulli, Livlæger der hos Christian IV og Frederik III vare benaadede med Kannikedømmer i Aarhus2, uden at de dog vides nogensinde at have opholdt sig der. Doktor Mathias Jacobsen, hvem Hertel kalder »Stamfader til de danske Maccabæer«, døde 15/5 1636 og efterlod sig en Søn Jakob Madsen (Jacobus Mathiae), som 1645 blev Biskop i Aarhus, samt 3 Døtre, der blev Stammemødre til store og ansete Slægter.3 Biskop Jacob Madsen (Jacobus Mathiae) f. -

Incentives, Technology and the Shift to Year-Round Dairying in Late 19Th Century Denmark

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics Incentives, Technology and the Shift to Year-Round Dairying in Late 19th Century Denmark Ingrid Henriksen Institute of Economics University of Copenhagen and Kevin H. O’Rourke Department of Economics and IIIS Trinity College Dublin October 2003 This is a revised version of a paper presented at the 5th EHES Congress, Madrid, July 2003. We are grateful to our discussant, James Simpson, and to the other participants at the congress for their helpful comments. We also wish to thank William Hynes, Jim McElroy, James Walker and Hampus Willfors for excellent research assistance, and Gunnar Persson for generous logistical and intellectual support. Henriksen acknowledges generous support from the Danish Social Science Research Council (grant number 890). O’Rourke is a IRCHSS Government of Ireland Senior Fellow, and acknowledges generous support from the Irish Research Council for the Humanities and Social Sciences. The usual disclaimer applies. Section 1. Introduction The grain invasion of the late 19th century has attracted a lot of attention from economic historians and political scientists, who have emphasised the distributional consequences of this episode, and the political responses which it provoked. There has been less written on European private sector responses to the globalization of agriculture which occurred at this time; this is unfortunate, since the ability of societies to adapt to such shocks is crucial for their long-term prosperity. One exception is the literature on Denmark’s agricultural transformation during this period. In particular, the success of the late 19th century Danish dairy industry has been noted by a diverse range of scholars and commentators, including Charles Kindleberger, Horace Plunkett, and H. -

Odense Bispestols Gods, Skifter 1731-1835 Knud Jeppesen, Snestrup, Pårup, 13-09-1782

1 Odense Bispestols gods, skifter 1731-1835 Knud Jeppesen, Snestrup, Pårup, 13-09-1782, I-2 (5) i far Jeppe Olesens gård ~ Dorthe Andersdatter, lavværge skoleholder Christian Seidler, Snestrup Jeppe Knudsen 6 år, værge ms. Jacob Østrup, Tarupgård Marie Knudsdatter 15 år, værge Jens Jensen, Trøstrup, Korup Anne Cathrine Knudsdatter 13 år, værge Jens Pedersen Fraugde Karen Knudsdatter 10 år, værge Niels Rasmussen, Villestofte Kirsten Knudsdatter 2 år, værge Jørgen Andersen, Snestrup Skiftedokument (80) Rasmus Rasmussen, Særslevhuset, Lumby, 22-05-1783, I-6 (9) ~ Anne Jørgensdatter, lavværge far Jørgen Andersen, Tarup Rasmus Rasmussen 3½ år, Værge farbror Hiere Rasmussen, Broby Jørgen Rasmussen 1½ år, værge farbror gårdmand Anders Rasmussen, Bellinge Afdødes mor Anne Hieresdatter er på aftægt i gården efter at have afstået til sønnen Skiftedokument (86) Maren Knudsdatter, Snestrup, Pårup, 03-03-1786, I-8b (12) ~ gårdmand Jeppe Olesen søn + Knud Jeppesens børn, hans enke Dorthe Andersdatter, lavværge ms. Seisler Jeppe Knudsen 10 år Maren Knudsdatter 19 år Anne Cathrine Knudsdatter 17 år Karen Knudsdatter 14 år Kirstine Knudsdatter 6 år Skiftedokument (99) Anne Jørgensdatter, Særslevhuset, Lumby, 03-08-1786, I-13 (16) ~ 1 Rasmus Rasmussen, Særslevhuset, Lumby, 22-05-1783, I-6 (9) Rasmus Rasmussen 7 år, værge farbror Hiere Rasmussen Jørgen Rasmussen 5 år, værge morbror Peder Jørgensen, Ensomhed, Snestrup ~ 2 Niels Pedersen Mette Nielsdatter 2 år Skiftedokument (107) Dorthea Rasmusdatter, Strandhuse, Ulbølle, 04-06-1787, 04-06-1787, I-17 (20)