Incentives, Technology and the Shift to Year-Round Dairying in Late 19Th Century Denmark

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

M/S Museets for Søfart Årbog 2012

SLÆGTSFORSKERNES BIBLIOTEK Dette værk er downloadet fra Slægtsforskernes Bibliotek Slægtsforskernes Bibliotek drives af foreningen Danske Slægtsforskere. Det er et privat special-bibliotek med værker, der er en del af vores fælles kulturarv omfattende slægts-, lokal- og personalhistorie. Støt Slægtsforskernes Bibliotek - Bliv sponsor Som sponsor i biblioteket opnår du en række fordele. Læs mere om fordele og sponsorat her: https://www.dsshop.dk/sponsorat Ophavsret Biblioteket indeholder værker både med og uden ophavsret. For værker, som er omfattet af ophavsret, må PDF-filen kun benyttes til personligt brug. Videre publicering og distribution uden for husstanden er ulovlig. Links Slægtsforskernes Bibliotek: https://bibliotek.dis-danmark.dk Danske Slægtsforskere: https://slaegt.dk Museet for Søfart Maritime Museum of Denmark ÅRBOG 2012 UDGIVET AF M/S MUSEET FOR SØFARTS VENNER M/S MUSEET FOR SØFARTS ÅRBOG Register til årbøgerne 1942-61 findes i årbog 1961, 2012-udgaven er bind 71 i rækken af museets årbøger til 1962-66 i årbog 1966, © M/S Museet for Søfart til 1967-71 i årbog 1971, til 1972-76 i årbog 1976, Redaktion: Jørgen Selmer og Benjamin Asmussen til 1977-81 i årbog 1982, Oversættelser: Charlotte Lindhardt, forfatterne og til 1982-86 i årbog 1986, redaktionen til 1987-91 i årbog 1991, til 1992-96 i årbog 1997, ISBN 978-87-7015-006-4 til 1997-01 i årbog 2002, ISSN 0085-1418 til 2002-06 i årbog 2007, til 2007-11 i denne årbog. Grafisk formgivning: Peter Dyrvig Grafisk Design Bogen er sat med Myriad Pro og ITC Laurel Årbøgerne 1942-2008 er frit tilgængelige på Trykt hos Zeuner Grafisk museets hjemmeside. -

Incentives, Technology and the Shift to Year-Round Dairying in Late 19Th Century Denmark

Incentives, Technology and the Shift to Year-Round Dairying in Late 19th Century Denmark Ingrid Henriksen Institute of Economics University of Copenhagen and Kevin H. O’Rourke Department of Economics and IIIS Trinity College Dublin October 2004 This is a revised version of a paper presented at the 5th EHES Congress, Madrid, July 2003. We are grateful to our discussant, James Simpson, and to the other participants at the congress for their helpful comments. We also thank William Hynes, Jim McElroy, James Walker and Hampus Willfors for excellent research assistance, Gunnar Persson for generous logistical and intellectual support, Jan Tore Klovland for making his monthly price data available to us, Rob Sollis for technical advice, and the anonymous referees who helped improve the paper substantially. Henriksen acknowledges generous support from the Danish Social Science Research Council (grant number 890). The paper was written while O’Rourke was an IRCHSS Government of Ireland Senior Fellow, and he acknowledges generous support from the Irish Research Council for the Humanities and Social Sciences. The usual disclaimer applies. Section 1. Introduction The grain invasion of the late 19th century has attracted a lot of attention from economic historians and political scientists, who have emphasised the distributional consequences of this episode, and the political reactions which it provoked. There is also a substantial literature on Denmark’s agricultural transformation during this period, which came as a direct response to growing imports of cheap overseas grain. In particular, the success of the late 19th century Danish dairy industry has been noted by a diverse range of scholars and commentators, including Charles Kindleberger, Horace Plunkett, and H. -

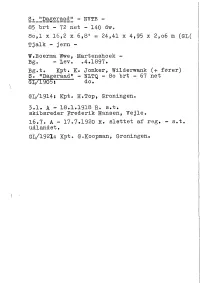

85 Brt - 72 Net - 140 Dw

S^o^^Dageraad*^ - WVTB - 85 brt - 72 net - 140 dw. 8o,l x 16,2 x 6,8' = 24,41 x 4,95 x 2,o6 m (GL( Tjalk - jern - W.Boerma Wwe, Martenshoek - Bg. - lev. .4.1897. Bg.t. Kpt. Ko Jonker, Wilderwank (+ fører) S. "Dageraad" - NLTQ - 8o brt - 67 net GI/1905: do. GL/1914: KptO H.Top, Groningen. 3.1. A - 18.1.1918 R. s.t. skibsreder Frederik Hansen, Vejle, 16.7. A - 17.7.1920 R. slettet af reg. - s.t. udlandet. Gl/1921: Kpt. G.Koopman, Groningen. ^Dagmar^ - HBKN - , 187,81 hrt - 181/173 NRT - E.C. Christiansen, Flenshurg - 1856, omhg. Marstal 1871. ex "Alma" af Marstal - Flb.l876$ C.C.Black, Marstal. 17.2.1896: s.t. Island - SDagmarS - NLJV - 292,99 brt - 282 net - lo2,9 x 26,1 x 14,1 (KM) Bark/Brig - eg og fyr - 1 dæk - hækbg. med fladt spejl - middelf. bov med glat stævn. Bg. Fiume - 1848 - BV/1874: G. Mariani & Co., Fiume: "Fidente" - 297 R.T. 29.8.1873 anrn. s.t. partrederi, Nyborg - "DagmarS - Frcs. 4o.5oo mægler Hans Friis (Møller) - BR 4/24, konsul H.W. Clausen - BR fra 1875 6/24 købm. CF. Sørensen 4/24 " Martin Jensen 4/24 skf. C.J. Bøye 3/24 skf. B.A. Børresen - alle Nyborg - 3/24 29.12.1879: Forlist p.r. North Shields - Tuborg havn med kul - Sunket i Kattegat ca. 6 mil SV for Kråkan, da skibet ramtes af brådsø, der knækkede alle støtter, ramponerede skibets ene side, knuste båden og ødelagde pumperne. -

Danske Skibe I Tysk Malmfart^ Under 2. Verdenskrig

Ole Stig Johannesen: rVialmfarten - danske skibe i tysk malmfart^ under 2. verdenskrig Forfatteren er lektor cand. mag. i fransk, tysk og lænderne nedkastede store mængder af russisk, men har også en maritim fortid. Han miner i håb om at spærre for gennemsej har desuden skrevet bøger om rederierne ØK, Ove lingen i Øresund og Bælterne. En tysk Skou, Dansk-Fransk ogA.P. Møller-Mærsk. Der minespærring blev lagt tværs over Skager er aldrig før foretaget en undersøgelse i Fragt rak fra Danmark til Norge, så at ingen bri nævnets arkiv2> med henblik på at finde frem til tiske krigsskibe kunne dukke op i de dan skibene i den pågældende malmfart. Såvel antal ske farvande - og de danske handelsfar- let af skibe som omfanget af den transporterede tøjer kunne heller ikke slippe ud. De gen mængde af jernmalm virker overraskende. sidige mineringer omfattede både hornmi nerne, der eksploderede ved kontakt med De generelle forhold for skibsfarten skibet samt de mere udspekulerede mag i de danske farvande netiske miner, der kunne indstilles, så at Med den tyske besættelse af Danmark i der skulle et vist antal oversejlinger til, før april 1940 blev handelsflåden som bekendt de udløstes. Der blev foretaget minestryg delt op i den del, der var i udenrigsfart og ninger, og al sejlads foregik i disse tvangs således uden for Tysklands rækkevidde og i ruter, der kun var nødtørftigt afmærkede. den del, der befandt sig i de hjemlige Havnefogeden udleverede sejladsanvisnin farvande og som følge heraf blev underlagt ger til skibets kaptajn umiddelbart før ski tyske krav. Det var ca. -

Aarhus Storborgerslægter.Pdf

Kilde J. Hoffmeyer: "Blade af Aarhus Byes Historie". I. (2. Halvbind, 1906) Aarhusianske Storborgerslægter i Slutningen af 17. Aarhundrede. I Begyndelsen af det syttende Aarhundrede levede der i Aarhus en højt anset Læge ved Navn Mathias (Mads) Jacobsen eller Jacobæus, Phil. Med. Doctor f. 1570. Han var Søn af en Biskop i Odense, Jacob Madsen, (Vejle), havde i sine yngre Dage rejst i Tyskland, Sicilien, Frankrig og England, samt indtaget en fremragende Stilling som Lærd i Padua. I Aaret 1614 udnævntes han til Livlæge hos Kong Christian IV, men tog sin Afsked fra Hoffet, og da han hørte til en gammel Aarhusslægt, bosatte han sig i Aarhus og blev gift med Ingeborg Johanne (d. 1620) en Datter af Biskop Jens Giødesen (Janus Ægidius (d. 1626).1 I Aarhus levede han Størstedelen af sit Liv som Prælat i Domkapitlet og boede vistnok i en Kannikegaard, som har ligget i Kannikegade, der hvor Grosserer Schourups Gaard nu ligger. Forresten nævnes han ogsaa som Ejer af enkelte an- dre Grunde i Aarhus. At en Læge var Medlem af Domkapitlet var i hine Tider ingen Sjældenhed, baade Doct. med. Jacob Fabricius og Doct. med. Simon Paulli, Livlæger der hos Christian IV og Frederik III vare benaadede med Kannikedømmer i Aarhus2, uden at de dog vides nogensinde at have opholdt sig der. Doktor Mathias Jacobsen, hvem Hertel kalder »Stamfader til de danske Maccabæer«, døde 15/5 1636 og efterlod sig en Søn Jakob Madsen (Jacobus Mathiae), som 1645 blev Biskop i Aarhus, samt 3 Døtre, der blev Stammemødre til store og ansete Slægter.3 Biskop Jacob Madsen (Jacobus Mathiae) f. -

Tegn Venligst Nye Medlemmer - Derved Støtter De Selskabets Formål at Virke for Forøgelse Og Forbedringer Af Handels- Og Søfartsmuseets Samlinger

Tegn venligst nye medlemmer - derved støtter De selskabets formål at virke for forøgelse og forbedringer af Handels- og Søfartsmuseets samlinger. Indmeldelse modtages på museet. Medlemmernes rettigheder: Gratis adgang til Handels- og Søfartsmuseets samlinger på Kronborg slot. Selskabet yder gratis sine medlemmer en smuk og Interes sant Illustreret årbog, hvis værdi overstiger minimums kontingentet. Medlemmerne kan for betydeligt nedsat pris købe de af museet udgivne Søhistoriske skrifter (se omslagets tredie side), samt ældre årbøger, 1943-56 pr. stk. kr. 3.50, 1957-60 kr. 5- pr. stk.). Bestillinger modtages på Handels- og Søfartsmuseet. Minimumskoniing enter: Arsmedlemmer kr. 15- årligt for personer, kr. 100- for Institutioner eller firmaer. Personer kan blive livsvarige medlemmer for et mini mumsbeløb af kr. 200- én gang for alle. SELSKABET „HANDELS- OG SØFARTS MUSEETS VENNER" BERETNING for REGNSKABSÅRET 1960 „Handels- og Søfartsmuseets Venner" afholdt sin ordinære general forsamling i Kongens Kammer på Kronborg Slot onsdag d. 29. juni 1960. Direktør H. Westergaard valgtes til dirigent. I sin beretning omtalte formanden, professor, dr. techn. G. W. Pro haska, at året 1959 havde været et roligt år for museet. De to model ler, der var under arbejde og tænktes skænket til museet, nemlig en fiskejagt fra 1778 og vagerkutteren „Løvenørn", havde endnu ikke kunnet afleveres, da modelbyggerne har været sinket af andet arbejde. Imidlertid havde der vseret lejlighed til at forære museet en række genstande af forskellig art, som museet har ønsket sig, nemlig et hol landsk flisebillede forestillende en „staatenyacht", et par fajancekop per med helsingørske motiver 1 transferprint, tre skibsbilleder (brig „Konig von Danemark" af Altona af så tidlig en dato som ca. -

American Rights & British Pretensions on the Seas;

GIass_ D^35~ Book. ^_ The Facts—and the Documents AMERICAN RIGHTS & BRITISH PRETENSIONS On the Seas At Book-stores and News-stands, One Dollar y 5 AMERICAN RIGHTS & BRITISH PRETENSIONS on the SEAS 2 ?±^ The Facts and the Documents, Official and Other, Bearing upon the Present Attitude of Great Britain toward the Commerce of the United States Compiled, with introductory memoranda, by WILLIAM BAYARD HALE New York Robert M. McBride & Company 191 3^ Copyright, 19 15, by William Bayard Hale CONTENTS I The First Encroachments II The Summit of Arrogance III Ships and Cargoes Stopped at Sea IV The Case of Cotton V Indirect Interference with Trade VI Interference with Communication VII Our Larger Interests VIII List of Ships Detained IX Quotations Pertinent to the Issue X Official Documents XI Diplomatic Correspondence The Government of Great Britain has virtually set up in the midst of the busy seas an arbitrary court, claiming unheard-of powers and exercising the most tyrannous police functions; seiz- ing and haling into the dock as suspects all travelers upon the ocean highways, and visiting many of them with heavy penalties for unproven, and indeed unprovable, offenses. This lawless assizes of the seas, contemptuous alike of its own precedents and of the rights of others, scarcely stoops to the pretense of citing authority for its actions, which are determined solely by its brutal will, and enforced, though indeed largely through intimidation, by the gigantic power of its naval police. The extent of the earth's surface over which this extraordinary court is permitted to wield its self-arrogated jurisdiction, the magnitude of the in- terests which its actions vitally affect, and the supineness with which sovereign States submit to the erection, upon the ruins of their self-respect and the debacle of their highest commercial and political interests, of an island's municipal statutes into inter- national formulas, unite to render this one of the spectacles of history. -

How the Danes Discovered Britain: the International Integration of the Danish Dairy Industry Before 1880

European Historical Economics Society ! EHES!WORKING!PAPERS!IN!ECONOMIC!HISTORY!!|!!!NO.!66! How the Danes Discovered Britain: The International Integration of the Danish Dairy Industry Before 1880 Markus Lampe Universidad Carlos III Madrid Paul Sharp University of Southern Denmark OCTOBER!2014! ! EHES!Working!Paper!|!No.!66!|!October!2014! How the Danes Discovered Britain: The International Integration of the Danish Dairy Industry Before 1880 Markus Lampe* Universidad Carlos III Madrid Paul Sharp** University of Southern Denmark Abstract The success of Danish agricultural exports at the end of the nineteenth century is often attributed to the establishment of a direct trade with Britain. Previously, exports went mostly via Hamburg, but this changed with the loss of Schleswig and Holstein to Prussia in the war of 1864. After this, quantity and price data imply narrowing price gaps and thus imply gains for Danish producers. Why then did Denmark not discover the British market earlier? We show that butter markets in both countries were integrated in the eighteenth century, but through the Hamburg hub. We then demonstrate that there were sound economic reasons for this well into the nineteenth century. However, movements to establish a direct trade were afoot from the 1850s. Thus, although the war certainly gave an extra boost to the process, the shock from the loss of the Duchies was not necessary for the future Danish success. JEL classification: F1, L1, N5, N7, Q1 Keywords: Butter, dairies, Denmark, hubs, international trade, market integration Acknowledgements: We would like to thank Per Boje, Ingrid Henriksen, Eoin McLaughlin, and participants at seminars and conferences for their advice and suggestions. -

Helsingør Værft 1882 -1982

HELSINGØR VÆRFT 1882 -1982 Af HANNE POULSEN Om et værft, der har været i virksomhed i hundrede år, kan skrives bøger om arbejdslivet, de tekniske fremskridt og om produktet. Når det gælder en så alsidig industrivirksomhed som Helsingør Værft, er det især svært at begrænse fremstil lingen. Forfatteren har valgt at lægge hovedvægten på det samspil mellem reder og værft, der har skabt Helsingør Værfts specielle image. Den 1. marts 1982 var det hundrede år siden, at de offentlige myndig heder indvilligede i at fremleje arealet mellem Kronborg og Barfoed & Rohmanns træskibsværft til aktieselskabet Helsingørs Jernskibs- og Maskinbyggeri. Koncessionen til værftets oprettelse var i novem ber 1881 blevet overdraget grosserer og skibsreder M.C. Holm og skibsbygmester Vilh. Dyhr. Mads Holm, Værftets grundlægger Mads Holm var født i Nykøbing Mors i 1827 som et efter tidens sprog brug »uægte« barn af væverpige og kogerske Maren Nielsdatter, men i 1838 blev moderen gift med tøffelmager Lars Holm, der lyste dren gen i kuld og køn. Mads Christians store interesse var skibsbyggeriet, og han kom i lære som skibstømrer hos skibsbygger Berthel Holm i Nykøbing. Mester var dog ikke tilfreds med sin læredreng, der måtte flytte til Thisted, hvor skibsbygger Strand helt anderledes forstod og påskønnede den lidt sære og allerede da ambitiøse lærling. Om Holm udtalte Strand senere, at da han havde været to år i lære, kunne han måle sig med de fleste svende. Mads Holm blev svend i 1846 og arbej dede et årstid på skibsbygmester Paghs værft i Ålborg, før han aftjen te sin værnepligt til orlogs. Herefter tog Mads Holm til Helsingør og fik arbejde på træskibsværftet. -

Mejlby Sogns Historie / Bind II

Dette værk er downloadet fra Slægtsforskernes Bibliotek Slægtsforskernes Bibliotek er en del af foreningen DIS- Danmark, Slægt & Data. Det er et special-bibliotek med værker, der er en del af vores fælles kulturarv, blandt andet omfattende slægts-, lokal- og personalhistorie. Slægtsforskernes Bibliotek: http://bibliotek.dis-danmark.dk Foreningen DIS-Danmark, Slægt & Data: www.slaegtogdata.dk Bemærk, at biblioteket indeholder værker både med og uden ophavsret. Når det drejer sig om ældre værker, hvor ophavs-retten er udløbet, kan du frit downloade og anvende PDF-filen. Når det drejer sig om værker, som er omfattet af ophavsret, er det vigtigt at være opmærksom på, at PDF-filen kun er til rent personlig, privat brug. MEJLBY SOGNS HISTORIE II S. A. POULSEN PO VL JØRGENSEN GA A^D EJER LEKTOR AARHUS AARHUS AMTSTIDENDES BOGTRYKKERI 1 9 4 2 INDHOLDSFORTEGNELSE Kort over Mejlby Sogn i 1816. Forord ......................................................... VII Matr. Nr. 1 (Annexgaarden) ................. 1 Matr. Nr. 2 ................................................ 4 Matr. Nr. 3 ................................................ 6 Matr. Nr. 4 ................................................ 11 Matr. Nr. 5 (Stiftsgaarden) ................. 15 Matr. Nr. 6—7 .......................................... 19 Matr. Nr. 8 (Enggaard) ........................ 24 Matr. Nr. 9 (Vennelund) og 21 (Dyr- gaard ....................................................... 27 Matr. Nr. 10 ............................................. 40 Matr. Nr. 11 og 12 ................................ -

V Ol. LVIII, No. 3 the ECONOMIC HIST OR Y REVIEW August 2005

V ol. LVIII, No. 3 ol. LVIII, CONTENTS VOLUME LVIII, NO. 3 AUGUST 2005 ARTICLES JOHN MUNRO Spanish merino wools and the nouvelles draperies: an industrial transformation in the late medieval Low Countries SAMANTHA WILLIAMS Poor relief, labourers’ households and living standards in rural England c.1770–1834: a Bedfordshire case study INGRID HENRIKSEN AND KEVIN H. O’ROURKE THE ECONOMIC HISTORY REVIEW Incentives, technology, and the shift to year-round dairying in late nineteenth-century Denmark JIM TOMLINSON Managing the economy, managing the people: Britain c.1931–70 NOTE JEREMY ATACK, FRED BATEMAN, AND ROBERT A. MARGO Capital deepening and the rise of the factory: the American experience during the nineteenth century BOOK REVIEWS August 2005 This journal is available online at Blackwell Synergy. Visit www.blackwell-synergy.com to search the articles and register for table of contents e-mail alerts. 0013-0117(200508)58:3;1-# Blackwell Publishing Ltd.Oxford, UK and Malden, USAEHRThe Economic History Review0013-0117Economic History Society 20052005LVIII3520554ArticlesYEAR-ROUND DAIRYING IN LATE NINETEENTH- CENTURY DENMARKINGRID HENRIKSEN AND KEVIN H. O’ROURKE Economic History Review, LVIII, 3 (2005), pp. 520–554 Incentives, technology and the shift to year-round dairying in late nineteenth-century Denmark1 By INGRID HENRIKSEN and KEVIN H. O’ROURKE he grain invasion of the late nineteenth century has attracted a lot of Tattention from economic historians and political scientists, who have emphasized the distributional consequences of this episode, and the politi- cal reactions which it provoked. There is also a substantial literature on Denmark’s agricultural transformation during this period, which came as a direct response to growing imports of cheap overseas grain. -

FO-Aarhus.Dk Foredragskatalog 2014

Foredragskatalog 2014 - 16 FO 46 45 00 87 C, Tlf. Aarhus 78C, 8000 Frederiksgade - Aarhus Foto: Jens Fredslund Se foredragskatalogets hjemmeside på: http://foredrag.fo-aarhus.dk FO-Aarhus.dk - fordi netværk handler om mennesker 2 Foredragskatalog Til lokalcentre, plejehjem, foredragsforeninger, menighedsråd, klubber, højskoler mv. Hos FO-Aarhus vil vi gerne bidrage til at gøre væsentlige emner til samtalestof. Velkommen og god fornøjelse med FO-Aarhus’ foredragskatalog 2014/2016! 3 4 Indholdsfortegnelse og et par gode tilbud Emner: side Praktiske oplysninger 6 Musikforedrag 7 Livshistorier og skæbnefortællinger 24 Kunst og kunstnere 29 Historie 21 Lokalhistorie 39 Danmark dejligst 42 Litteratur 46 Tro, etik og filosofi 51 Menneskeliv og samfund 54 Rejser og møder med andre kulturer 58 Humor og drama 70 Jul 72 Foredragsholdere i alfabetisk orden 74 Særlige tilbud fra FO-Aarhus i dette katalog: Læs om Seniordaghøjskolen på side 23 Kom Ud af Røret!!! Mulighed for undervisning i dit lokalområde! Læs mere på side 28 og s. 69 Ønsker I at sammensætte jeres eget højskoleforløb i egne lokaler med hjælp fra FO-Aarhus? Se hvordan på side 41 Gratis foredrag! Se vores gode tilbud på side 71 5 Praktiske oplysninger værd at vide FO-Aarhus har hermed fornøjelsen af at kunne opmærksom på at kørselspenge skal afregnes præsentere vort nye foredragskatalog for direkte med foredragsholderen i forbindelse med 2014/2016. Fremover vil der kun blive udgivet et foredraget. Undersøg evt. dette på kontoret nyt katalog hver andet år. Kataloget har været samtidig med bestilling. igennem en gennemgribende revidering, som bl.a. indebærer kortere foredragsbeskrivelser. En mere Copydan udførlig beskrivelse kan findes på vores De i kataloget nævnte priser er det beløb, hjemmeside http://foredrag.fo-aarhus.dk/.