Full Text of UNSC Resolution 751 Available at [ Doc.Asp?Symbol=S/RES/751(1992)], Accessed April 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“What Could Possibly Go Wrong?”

“WHAT COULD POSSIBLY GO WRONG?” SECRET DEAL ALLOWS COMPANY TIED TO SADDAM’S NUCLEAR BOMBMAKER, IRAN AND U.A.E. TO MANAGE KEY FLORIDA PORT FACILITIES An Occasional Paper of the Center for Security Policy By: Alan Jones and Mary Fanning 23 December 2016 1 Gulftainer’s Port Canaveral cargo container terminal (left), Saddam Hussein awarding a medal to Iraqi nuclear physicist Dr. Jafar Dhia Jafar, considered the “father of Iraq’s nuclear weapons program” (right) In 2015 President Barack Obama’s Administration quietly approved the hand-over of cargo container operations at Florida’s Port Canaveral to Gulftainer, a Middle Eastern ports company owned by the Emir of Sharjah of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Iraqi businessman Hamid Dhia Jafar. Hamid Jafar is the brother and the business partner of Dr. Jafar Dhia Jafar -- the Baghdad-born nuclear physicist who masterminded Saddam Hussein’s nuclear weapons program. UAE-based port operator Gulftainer, a subsidiary of The Crescent Group, was awarded the 35- year no-bid lease at Port Canaveral in 2014 following two years of secret talks in a deal code-named “Project Pelican.” Treasury Secretary Jacob “Jack” Lew declined1 to conduct a Committee on Foreign Investment (CFIUS) National Security Threat Analysis that, under the Foreign Investment & National Security Act of 2007 (FINSA), is required for transactions affecting America’s critical infrastructure and U.S. national security. Port Canaveral is in close proximity to a U.S. Navy nuclear submarine base, two U.S. Air Force Space Command bases, and NASA’s Kennedy Space Center. Gulftainer has port operations in the UAE, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, Pakistan, Turkey, Brazil, and Russia. -

The New Iraq: 2015/2016 Discovering Business

2015|2016 Discovering Business Iraq N NIC n a o t i io s n is al m In om in association with vestment C USINESS B Contents ISCOVERING Introduction Iraq continues as a major investment opportunity 5 Messages - 2015|2016 D - 2015|2016 Dr. Sami Al-Araji: Chairman of the National Investment Commission 8 RAQ HMA Frank Baker: British Ambassador to Iraq 10 I Baroness Nicholson of Winterbourne: Executive Chairman, Iraq Britain Business Council 12 EW N Business Matters HE Doing business in Iraq from a taxation perspective - PricewaterhouseCoopers 14 T Doing business in Iraq - Sanad Law Group in association with Eversheds LLP 20 Banking & Finance Citi has confidence in Iraq’s investment prospects - Citi 24 Common ground for all your banking needs - National Bank of Iraq 28 Iraq: Facing very challenging times - Rabee Securities 30 2005-2015, ten years stirring the sound of lending silence in Iraq - IMMDF 37 Almaseer - Building on success - Almaseer Insurance 40 Emerging insurance markets in Iraq - AKE Insurance Brokers 42 Facilitating|Trading Organisations Events & Training - Supporting Iraq’s economy - CWC Group 46 Not just knowledge, but know how - Harlow International 48 HWH shows how smaller firms can succeed in Iraq - HWH Associates 51 The AMAR International Charitable Foundation - AMAR 56 Oil & Gas Hans Nijkamp: Shell Vice President & Country Chairman, Iraq 60 Energising Iraq’s future - Shell 62 Oil production strategy remains firmly on course 66 Projects are launched to harness Iraq’s vast gas potential 70 Major investment in oilfield infrastructure -

USAF Counterproliferation Center CPC Outreach Journal #316

USAF COUNTERPROLIFERATION CENTER CPC OUTREACH JOURNAL Maxwell AFB, Alabama Issue No. 316, 6 February 2004 Articles & Other Documents: Dr. Kay Had Maps with Coordinates of WMD Hiding A Desert Mirage: How U.S. Misjudged Iraq's Arsenal Places in Syria Warhead Blueprints Link Libya Project To Pakistan Figure Pakistani Scientist Admits That He Passed On Nuclear Secrets N. Korea And U.S. Have Plenty To Discuss Government Refuses N. Korean Arms Offer New Detrick Lab In Works Ricin Partially Shuts Senate Letter With Ricin Vial Sent To White House Incident Illustrates Lapses In Security Net Ricin Poses Postal Risk, but Different From Germs It's Lethal, Easy To Make, But Impractical For Terror Ricin, Made From Common Castor Beans, Can Be Lethal Notable Events Involving Ricin But Has Drawbacks As A Weapon Bush Orders A Plan To Protect Food Supply From Terror Pakistani Finger-Pointing And Denials Spread In The Furor Over Attack Nuclear Transfers Abroad 1918 killer flu secrets revealed Rumsfeld Says Iraq Likely Had Arms Alleged Nuclear Offer To Iraq Is Revisited Foreign Source Seen As Unlikely In Ricin Mailings NATO plans special brigade to fight terror risks Tenet Defends CIA's Analysis Of Iraq as Objective, if Flawed Nuclear Expert Receives Pardon From Musharraf Key Source On Iraqi Bioweapons Was Deemed Dubious, Agencies Say In Response To Criticism, Tenet Reveals CIA Successes U.N. Nuclear Chief Warns Of Global Black Market Missed Signals On WMD? Senate Offices Open Again As Ricin Inquiry Continues Khan's Nuke Network Sparks Proliferation Fears EU states pressuring Syria over WMD - diplomats Welcome to the CPC Outreach Journal. -

Towards a Policy Framework for Iraq's Petroleum Industry and An

Towards a Policy Framework for Iraq’s Petroleum Industry and an Integrated Federal Energy Strategy Submitted by Luay Jawad al-Khatteeb To the University of Exeter As a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Middle East Politics In January 2017 The thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgment. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature ......................................................... i Abstract: The “Policy Framework for Iraq’s Petroleum Industry” is a logical structure that establishes the rules to guide decisions and manage processes to achieve economically efficient outcomes within the energy sector. It divides policy applications between regulatory and regulated practices, and defines the governance of the public sector across the petroleum industry and relevant energy portfolios. In many “Rentier States” where countries depend on a single source of income such as oil revenues, overlapping powers of authority within the public sector between policy makers and operators has led to significant conflicts of interest that have resulted in the mismanagement of resources and revenues, corruption, failed strategies and the ultimate failure of the system. Some countries have succeeded in identifying areas for progressive reform, whilst others failed due to various reasons discussed in this thesis. Iraq fits into the category of a country that has failed to implement reform and has become a classic case of a rentier state. -

Rim Nr.5-6-7-Aprilie-201.Pmd

SUMAR • Dezbatere: Putea România rezista militar în anii 1917-1918? – General-maior (r) dr. MIHAIL E. IONESCU – Motivaţie .............................. 1 – NEAGU DJUVARA ...................................................................................... 3 – LUCIAN DRĂGHICI .................................................................................. 7 – Prof. univ. dr. MARIA GEORGESCU ......................................................... 10 REVISTA DE ISTORIE – Colonel (r) prof. univ. dr. ION GIURCĂ .................................................... 14 MILITAR~ – General-maior (r) dr. MIHAIL E. IONESCU ............................................. 22 – SERGIU IOSIPESCU ................................................................................. 27 Publicaţia este editată de – Prof. univ. dr. GHEORGHE NICOLESCU .................................................. 39 Ministerul Apărării Naţionale, prin – Colonel (r) PETRE OTU ............................................................................ 49 Institutul pentru Studii Politice – ADRIAN PANDEA ...................................................................................... 55 de Apărare şi Istorie Militară, – Colonel (r) dr. VASILE POPA .................................................................... 58 membru al Consorţiului Acade- miilor de Apărare şi Institutelor • Istorie militară şi lingvistică pentru Studii de Securitate din – Dr. CRISTIAN MIHAIL – Influenţa limbajului militar (daco-)roman asupra cadrul Parteneriatului pentru limbii române (II) -

Democracy and Monarchy As Antithetical Terms?: Iraq's Elections of September 1954 Bishop, Elizabeth

www.ssoar.info Democracy and monarchy as antithetical terms?: Iraq's elections of September 1954 Bishop, Elizabeth Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Bishop, E. (2013). Democracy and monarchy as antithetical terms?: Iraq's elections of September 1954. Studia Politica: Romanian Political Science Review, 13(2), 313-326. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-447205 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de Democracy and Monarchy as Antithetical Terms? 313 Democracy and Monarchy as Antithetical Terms? Iraq’s Elections of September 1954 ELIZABETH BISHOP Historian Bernard Lewis observes: ”Americans tend to see democracy and monarchy in antithetical terms; in Europe, however, democracy has fared better in constitutional monarchies than in republics”1. Let us take this opportunity to consider elections held in the Hashemite Kingdom of Iraq during the Cold War, in order to assess how”democracy” fared during the years that country was a constitutional monarchy. As we do so, let’s keep Saad Eskander’s words in mind: ”You cannot have democracy in Iraq by just holding elections... You need to enable Iraq’s core of citizens to have free access to information, absolutely all, all of legislation. -

The a to Z of Middle Eastern Intelligence by Ephraim Kahana and Muhammad Suwaed, 2009

OTHER A TO Z GUIDES FROM THE SCARECROW PRESS, INC. 1. The A to Z of Buddhism by Charles S. Prebish, 2001. 2. The A to Z of Catholicism by William J. Collinge, 2001. 3. The A to Z of Hinduism by Bruce M. Sullivan, 2001. 4. The A to Z of Islam by Ludwig W. Adamec, 2002. 5. The A to Z of Slavery & Abolition by Martin A. Klein, 2002. 6. Terrorism: Assassins to Zealots by Sean Kendall Anderson and Stephen Sloan, 2003. 7. The A to Z of the Korean War by Paul M. Edwards, 2005. 8. The A to Z of the Cold War by Joseph Smith and Simon Davis, 2005. 9. The A to Z of the Vietnam War by Edwin E. Moise, 2005. 10. The A to Z of Science Fiction Literature by Brian Stableford, 2005. 11. The A to Z of the Holocaust by Jack R. Fischel, 2005. 12. The A to Z of Washington, D.C. by Robert Benedetto, Jane Dono- van, and Kathleen DuVall, 2005. 13. The A to Z of Taoism by Julian F. Pas, 2006. 14. The A to Z of the Renaissance by Charles G. Nauert, 2006. 15. The A to Z of Shinto by Stuart D. B. Picken, 2006. 16. The A to Z of Byzantium by John H. Rosser, 2006. 17. The A to Z of the Civil War by Terry L. Jones, 2006. 18. The A to Z of the Friends (Quakers) by Margery Post Abbott, Mary Ellen Chijioke, Pink Dandelion, and John William Oliver Jr., 2006 19. -

Despre Actualitatea Acestei Cărţi. Cuvânt Înainte De Conf. Univ. Dr. Mircea Alexandru 5 Argument 12 Parlamentul României

SUMAR Despre actualitatea acestei cărţi. Cuvânt înainte de conf. univ. dr. Mircea Alexandru 5 Argument 12 Parlamentul României (scurt istoric) 14 Miniştrii de Interne aî României (listă) 25 Preşedinţi ai Senatului 36 Preşedinţi ai Adunării Deputaţilor 37 Miniştrii de interne în birourile Senatului 39 Miniştrii de interne în birourile Adunării Deputaţilor 43 Biografii politice ale miniştrior de interne care au fost în fotoliul de preşedinte al forurilor legislative: Ştefan Golescu 49 Constantin Bosianu 51 Dimitrie Gr. Gkica 53 Ioan Emanoil Florescu 56 Nicolae Kretzulescu 58 Dimitrie A. Sturdza 60 Eugeniu Stătescu 62 George Gr. Cantacuzino 64 Petre S. Aurelian 66 Theodor Rosetti 68 Mihail Pherekyde 70 Nicolae îorga 72 Constantin Argetoiau 74 Emanoiui Costache Epureanu 76 Lascăr Catargiu 78 Miniştrii de interne in Parlamentul României . _ — 577 Ion C. Brătianu 80 Constantin A. Rosetti 83 George Mânu 85 Constantin P. Olănescu 87 Vasiie G. hforpm 89 Alexandru Vaida-Voevod 91 Alexandru Drăghici 94 Discursuri: M1HAIL KOGĂLNICEANU, „Să nu căutăm totdeauna la străini temelia drepturilor noastre." 99 ALEXANDRU MARGHILOMAN, „Ştim a impune tăcere preferinţelor noastre în vederea scopului obştesc de atins." 115 LASCAR CATARGIU, „Şi celor de la sate ... trebuie să le procurăm si lor mijloace de a-şi apăra viaţa, averea şi produsul muncii lor." 125 LASCĂR CATARGIU, „ Trebuie luată o măsură pentru ca noi să avem o staţiune de gendarmerie în fiecare comună." 128 ANASTASIE STOLOJAN, „ Legea Jandarmeriei, în loc să fie o lege de garanţie pentru cetăţeni, e un instrument politic. " 131 VASILE LASCAR, „Jandarmeria, aşa cum este organizată a adus servicii reale ţării. " 137 VASILE LASCAR, „ O lege bună poate îndrepta multe rele." 140 VASILE LASCAR, „Principiile Legii Poliţiei sunt: capacitatea, stabilitatea şi scoaterea poliţiei din luptele politice. -

Sabina Cantacuzino (1863‒1944) Era Cunoscută De Contemporani Ca „fiica Cea Mare a Lui Ion C

Sabina Cantacuzino (1863‒1944) era cunoscută de contemporani ca „fiica cea mare a lui Ion C. Brătianu“ și „sora cea mai mare a Brătienilor“ ‒ Ionel, Con- stantin (Dinu) și Vintilă. A făcut școală în particular, după obiceiul timpului, la moșia Florica, iar mai târziu la București, cu profesori renumiți (Spiru Haret, David Emmanuel, V.D. Păun etc.), încheindu-și studiile cu un examen de ba- calaureat susținut la Colegiul Sf. Sava. În 1885 s-a căsătorit cu doctorul Constantin Cantacuzino. A învățat de tânără să iubească teatrul, muzica, artele plastice, de- venind cu timpul proprietara unei importante colecții de pictură românească și de obiecte de artă populară. A contribuit la înființarea și funcționarea Muzeului de artă „Toma Stelian“ și a Universității Libere (asociație culturală aflată sub patronajul reginei, în cadrul căreia se organizau conferințe și concerte); și-a lăsat prin testament locuința din București ca sediu al unui „cămin pentru doctoranzi“, conceput ca o fundație academică. Pe lângă sprijinirea instituțiilor culturale, s-a dăruit asistenței publice: a lucrat o lungă perioadă la Așezământul Regina Elisabeta, a organizat un cămin de copii bazat pe sistemul Montessori, a condus Spitalul nr. 108 din București în timpul Primului Război Mondial, a fost președinta Asociației pentru Profilaxia Tuberculozei, a avut, în 1914, inițiativa înființării unui spital pentru tuberculoși. Împreună cu alți membri ai familiei, a rămas în București în tim pul ocupației militare germane din 1916‒1918 și a fost internată în 1917, timp de nouă luni, la Mânăstirea Pasărea. Memoriile ei, pe care a început să le scrie în 1921, când se împlineau o sută de ani de la naș- terea lui Ion C. -

Thesis (281.2Kb)

UNITED STATES POLICY TOWARDS ROGUE STATES A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Angelo State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF SECURITY STUDIES by: ROBERT E. STILES May 2011 Major: Security Studies UNITED STATES POLICY TOWARDS ROGUE STATES By Robert Stiles APPROVED: Dr. Bruce E. Bechtol Dr. William Taylor Dr. Robert Nalbandov Dr. John Osterhaut July 16, 2012 APPROVED Dr. Brian May Dean of the College of Graduate Studies Table of Contents Table of Contents...........................................................................................................1 Abstract..........................................................................................................................2 Literature Review...........................................................................................................3 Introduction....................................................................................................................8 Chapter One: Iraq........................................................................................................10 Chapter Two: Iran.......................................................................................................43 Chapter Three: North Korea.......................................................................................80 Conclusions................................................................................................................110 Bibliography..............................................................................................................113 -

Inventar Fond Kogalniceanu REGISTRU-1

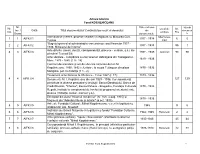

Arhiva Istorică Fond KOGĂLNICEANU Nr. Date extreme Număr Nr. Locul de Nr. Inv. / Cota Titlul documentului/ Conţinutul pe scurt al dosarului ale documen Crt. emitere File Dosar documentului te Acte diverse (cerere, procese verbale) în legătură cu Mircurea Ciuc, Miercurea- 1 1 AIFKI/1 1937 - 1938 6 5 Tuşnad Ciuc "Bugetul general al administraţiei comunale pe anul financiar 1937 - 2 2 AIFKI/2 1937 - 1938 56 1 1938. Ministerul de Interne". Acte diferite (cereri, decizii, corespondenţă, procese - verbale, ş.a.) ale 3 3 AIFKI/3 1937 - 1939 Jud.Ciuc 98 90 primăriei Tuşnad Băi. Acte vânzare - cumpărare a unor terenuri dobrogene din Taslageacul- 1879 - 1936 Mare. 1879 - 1880 (f. 9 - 14) Contract de arendare şi act de vânzare semnate de Ion M. Kogălniceanu. 1890; 1892 referitoare la moşia Tetlageac din plasa 1879 - 1936 Mangalia, jud. Constanţa (f. 1 - 2). Testament al lui Dimitrie G. Miclescu - 3 mai 1927 (f. 17). 1879 - 1936 44 AIFK I/4 Documente M. I. Kogălniceanu din anii 1929 - 1936. Corespondenţă 127120 primită de la diverse persoane şi instituţii: Banca Dorohoiului, Banca de Credit Român, "Chemix", Banca Rahova - Bragadiru, Fundaţia Culturală 1879 - 1936 Regală, invitaţie la campionatul de hochei (şi programul acestuia); acte diverse (chitanţe, avizuri, meniuri ş.a.). Exemplar din ziarul "Neamul românesc" (nr. 168, 4 aug. 1935) şi 1879 - 1936 fragment din "Adevărul literar şi artistic" (6 oct. 1935). Acte ale Fundaţiei Culturale Mihail Kogălniceanu: cereri în legătură cu 5 5 AIFKI/5 1945 9 6 imobilul din şos. Kisseleff. Înştiinţări ale Băncii Naţionale în legătură cu fondul "Fundaţiei Culturale 6 6 AIFKI/6 1942; 1945 Bucuresti 2 2 Mihail Kogălniceanu". -

Consiliul De Coroană CONSILIUL DE COROANĂ DIN 3 AUGUST 1914

CONSILIUL TEXTE DE Macrina Oproiu Izabela Török Corina Dumitrache COROANă Laura Avram —100 DE ANI DE la NEUTRALITATE Ionuţ Banu Se împlinește anul acesta un secol de la momentul istoric DOCUMENTE ARHIVă în care România şi-a decis orientarea antebelică, prin vocea Răzvan Radu oamenilor săi politici. Recenta istoriografie de specialitate, mai puţin conformistă decât în anii comunismului, DESIGN GRAFIC nu mai analizează circumstanţele evenimentului din Alexandru Duţă perspectivă strict ideologică şi propagandistică. Eliberată de barierele impuse de vechiul regim, etern sensibil Tipărit în România faţă de susceptibilităţile Moscovei, o parte importantă a istoriografiei ultimelor decenii încadrează Consiliul de AUGUST 2014 Coroană din 3 august 1914 într-un context mai larg, care © 2014 Muzeul Naţional Peleş nu ocoleşte abordarea contrafactuală şi care se sprijină pe o Nicio parte a acestei publicaţii amplă documentare de arhivă. nu poate fi reprodusă fără acordul scris al deţinătorilor drepturilor de autor. Regele Carol I .......................... 28 Vasile G. Morţun .................... 40 Principele Ferdinand .............. 30 Emanoil Porumbaru............... 41 Ion I.C. Brătianu ..................... 32 Alexandru G. Radovici .......... 42 Theodor Rosetti ..................... 33 Dr. Constantin Angelescu ..... 43 Petre P. Carp ............................ 34 Alexandru Marghiloman ....... 44 Mihail Pherekyde .................... 35 Ion Lahovari ............................ 45 Emil Costinescu ...................... 36 I. Grădişteanu .......................... 46 Ion Gheorghe Duca ................ 37 Take Ionescu ............................ 47 Victor Antonescu .................... 38 C. Cantacuzino Paşcanu ........ 48 Alexandru Constantinescu .... 39 Constantin G. Dissescu ......... 49 4 | | Consiliul de Coroană CONSILIUL DE COROANă DIN 3 AUGUST 1914. 100 DE ANI DE LA NEUTRALITATE Macrina Oproiu Muzeograf SE împlinește ANUL ACESTA UN SECOL DE LA din 15/28 iunie 1914 ar fi determinat MOMENTUL ISTORIC ÎN CARE ROMÂNIA şi-a oricum începutul unui conflict armat.