Whitman-Daniel.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DIRECTING the Disorder the CFR Is the Deep State Powerhouse Undoing and Remaking Our World

DEEP STATE DIRECTING THE Disorder The CFR is the Deep State powerhouse undoing and remaking our world. 2 by William F. Jasper The nationalist vs. globalist conflict is not merely an he whole world has gone insane ideological struggle between shadowy, unidentifiable and the lunatics are in charge of T the asylum. At least it looks that forces; it is a struggle with organized globalists who have way to any rational person surveying the very real, identifiable, powerful organizations and networks escalating revolutions that have engulfed the planet in the year 2020. The revolu- operating incessantly to undermine and subvert our tions to which we refer are the COVID- constitutional Republic and our Christian-style civilization. 19 revolution and the Black Lives Matter revolution, which, combined, are wreak- ing unprecedented havoc and destruction — political, social, economic, moral, and spiritual — worldwide. As we will show, these two seemingly unrelated upheavals are very closely tied together, and are but the latest and most profound manifesta- tions of a global revolutionary transfor- mation that has been under way for many years. Both of these revolutions are being stoked and orchestrated by elitist forces that intend to unmake the United States of America and extinguish liberty as we know it everywhere. In his famous “Lectures on the French Revolution,” delivered at Cambridge University between 1895 and 1899, the distinguished British historian and states- man John Emerich Dalberg, more com- monly known as Lord Acton, noted: “The appalling thing in the French Revolution is not the tumult, but the design. Through all the fire and smoke we perceive the evidence of calculating organization. -

State 1990-05: Iss

1 State (ISSN 0278-1859) (formerly the Depart¬ ment of State Newsletter) is published by the U.S. Department of State, 2201 C Street N.W., Washington, D.C. 20520, to acquaint its officers and employees, at home and abroad, with developments that may affect operations or per¬ sonnel. The magazine also extends limited coverage to overseas operations of the U.S. and Foreign Commercial Service of the Commerce Department and the Foreign Agricultural Service and the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service of the Agriculture Department. There are 11 monthly issues (none in August). Deadline for submitting material for publication is in the first week of each month. Contributions (consisting of general information, articles, poems, photographs, art work) are welcome. Di uble-space on typewriter, spelling out job titles, names of offices and programs—acronyms are not acceptable. Black-and-white, glossy- print photos reproduce best, but some color photos are acceptable. Each photo needs a cap¬ tion, double-spaced, identifying all persons left to right. Send contributions to STATE magazine, THE COVER—This is the TVeaty Room on the DGP/PA, Room B-266. The office telephone seventh floor, showing the entrance to the Secre¬ number is (202) 647-1649. tary’s office. This view and others, with commentary, will be part of a one-hour TV spe¬ Although primarily intended for internal com¬ cial, “America’s Heritage,” that will be munications, State is available to the public broadcast May 30 at 10:30 p.m. on Channel 26 through the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. in Washington. -

War Prevention Works 50 Stories of People Resolving Conflict by Dylan Mathews War Prevention OXFORD • RESEARCH • Groupworks 50 Stories of People Resolving Conflict

OXFORD • RESEARCH • GROUP war prevention works 50 stories of people resolving conflict by Dylan Mathews war prevention works OXFORD • RESEARCH • GROUP 50 stories of people resolving conflict Oxford Research Group is a small independent team of Oxford Research Group was Written and researched by researchers and support staff concentrating on nuclear established in 1982. It is a public Dylan Mathews company limited by guarantee with weapons decision-making and the prevention of war. Produced by charitable status, governed by a We aim to assist in the building of a more secure world Scilla Elworthy Board of Directors and supported with Robin McAfee without nuclear weapons and to promote non-violent by a Council of Advisers. The and Simone Schaupp solutions to conflict. Group enjoys a strong reputation Design and illustrations by for objective and effective Paul V Vernon Our work involves: We bring policy-makers – senior research, and attracts the support • Researching how policy government officials, the military, of foundations, charities and The front and back cover features the painting ‘Lightness in Dark’ scientists, weapons designers and private individuals, many of decisions are made and who from a series of nine paintings by makes them. strategists – together with Quaker origin, in Britain, Gabrielle Rifkind • Promoting accountability independent experts Europe and the and transparency. to develop ways In this United States. It • Providing information on current past the new millennium, has no political OXFORD • RESEARCH • GROUP decisions so that public debate obstacles to human beings are faced with affiliations. can take place. nuclear challenges of planetary survival 51 Plantation Road, • Fostering dialogue between disarmament. -

Part Three Greatest Hits: Outstanding Contributions to the Towson University Journal of International Affairs

TOWSON UNIVERSITY JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS VOL. L, NO. 1 PART THREE GREATEST HITS: OUTSTANDING CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE TOWSON UNIVERSITY JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS 49 FALL 2016 MAKE NO DRONES ABOUT IT Make No Drones About It: Evaluating the U.S. Drone Program Based On Domestic Policy Standards Jacob Loewner Abstract: United States policymakers have set strict standards on the parameters of drone use. They have thereby lain out before the public an idealized narrative of the effectiveness of drones, as well as the restraint with which they are used. Beyond this lofty rhetoric, however, the U.S. government has been incredibly reluctant to furnish information on its drone program. To complicate matters further, the rhetoric on the drone program put out by the administration is rarely corroborated by facts on the ground due to frequent civilian deaths, signature strikes, and the targeting of Americans. This piece analyzes the realities of the drone program against the backdrop of the idealized rhetoric laid out by the Obama Administration and finds that the rhetoric is not supported by the facts on the ground. As such, the piece argues for increased transparency and more effective human intelligence to be applied to the drone program. Introduction In January 2015, the United States conducted a drone strike that led to three deaths which had enormous and widespread consequences. A drone strike targeting an Al Qaeda compound on the border between Pakistan and Afghanistan led to the death of Ahmed Farouq, an Al Qaeda leader and American -

DE CARTER Y SUÁREZ a TRUMP Y RAJOY • Mariano Rajoy Visita El 26

Septiembre 2017 DE CARTER Y SUÁREZ A TRUMP Y RAJOY • Mariano Rajoy visita el 26 de septiembre la • EEUU es el primer inversor en España, pues re- Casa Blanca. Se reunirá con el Presidente de los gistra un 14,3% del total de las inversiones realiza- Estados Unidos, Donald Trump. Es su segunda vi- das en nuestro país. A la vez, el país americano es sita al Despacho Oval como Presidente: en enero el segundo destino de la inversión española: el de 2014 fue recibido por Barack Obama. 14% de esta se realiza en Estados Unidos. • La reunión entre los dos líderes se realiza en • En euros, las exportaciones se situaron en 2016 pleno Mes de la Herencia Hispana; conmemora- en 11.327,6 millones y las importaciones ascen- ción con origen en 1968 y que se celebra con ca- dieron a 13.015 millones. En el primer semestre rácter mensual entre el 15 de septiembre y 15 de de 2017, las exportaciones suponen 6.242 millo- octubre desde 1988. Durante este tiempo se re- nes y las importaciones 6.903 millones (+8,6% y cuerda la contribución hispana a la historia y la +5% sobre el mismo período de 2016). cultura estadounidenses. España, aliado estratégico de Estados Unidos • En sus ocho meses en el cargo, el Presidente Trump ha centrado sus prioridades en reducir la • España es uno de los principales socios euro- regulación, en la inmigración y en la seguridad peos, especialmente tras el Brexit. Al apartado nacional. Para ello, ha hecho uso de sus prerroga- económico hay que sumar el militar: la base aero- tivas mediante el empleo de órdenes ejecutivas naval de Rota (Cádiz) y la aérea de Morón (Sevilla). -

BUSINESS Israel Frees 300 of Its Shiite Prisoners

0 to MANCHESTER HERALD, Tuesday. July 2, 1985 MANCHESTER FOCUS BOLTON WEATHER BUSINESS MACC gets $127,000 Put some cool into Cheney takes helm j I Mostly fair tonight; to help with shelter those summer meals on Board of Selectmen j sunny on Thursday Apartment leases/Tandmine for unsuspecting ... page 4 ... page 13 ... page 4 ... page 2 put In writing to the landlord, or the landlord may learned this lesson the really hard w a y !) Do you feel queasy whenever you have to sign a Of course, everything written above refers to what abrogate the lease. lease because you fear that, more often than not, the is known in the trade as a landlord's lease. And a landlord has language in the lease that lets him walk SUII another common clause, says Bates "is like a sneak rider on a piece of legislation." You, the tenant, landlord can no more absolve himself of liability for all over your rights? Your negligence than can the owner of a parking lot. But if Do you realize that one of the toughest clauses in the agree that the storerooms are provided and Money's mainUined gratuitously by the landlord; you, in turn, you are desperate for a place to live, at least find out standard lease agreement provideslhat you, a tenant, what you are getting into. may be evicted with five days notice if your landlord agree that if you or your family use the storerooms, it Worth shall be at your own proper risk; the landlord is not to In addition to prohibitions against children and deems your conduct objectionable or improper? And pets, you might be handed a lease that restricts what another toughie is that even if such essential services Sylvia Porter be or become liable thereby for any loss or damage to persons or property because of such use. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS February 20, 1991 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

3854 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS February 20, 1991 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS NATIONAL RECYCLING RESOURCE States and several national parks that require comprehensive recycling, contending that a ACT INTRODUCED them by law. deposit law will hamper curbside recycling pro But, a new General Accounting Office grams by removing the most valuable scrap [GAO] report says that, faced with a growing materials in the waste stream. They argue that HON. PAUL B. HENRY solid waste dilemma, litter problems, and tight curbside recycling programs need the revenue OF MICHIGAN budget constraints, a national deposit system from the sale of bottles and cans to pay for IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES could "play a significant role in helping the Na operating costs. Even though curbside recy Wednesday, February 20, 1991 tion meet EPA's 25 percent solid waste reduc cling programs rely almost entirely on govern tion goal." Further, the report underlines the ment subsidies to offset both operating and Mr. HENRY. Mr. Speaker, today I am intro fact that more than 70 percent of Americans capital costs, this argument has provided polit ducing the National Recycling Resource Act of say it is time for the entire Nation to return to ical cover for a number of Members who might 1991. a commonsense, reuse-and-recycle deposit otherwise support a national deposit law. But With the forthcoming reauthorization of the system. Ironically, the same industries that in the GAO analysis destroys this argument. Resource Conservation and Recovery Act vented the returnable refund system continue The GAO report makes it clear that all nine [RCRA], we will soon be examining proposals to exert their special interest political power to deposit-law States have successful curbside that seek to ease our Nation's growing solid block deposit legislation. -

University of London Oman and the West

University of London Oman and the West: State Formation in Oman since 1920 A thesis submitted to the London School of Economics and Political Science in candidacy for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Francis Carey Owtram 1999 UMI Number: U126805 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U126805 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 bLOSiL ZZLL d ABSTRACT This thesis analyses the external and internal influences on the process of state formation in Oman since 1920 and places this process in comparative perspective with the other states of the Gulf Cooperation Council. It considers the extent to which the concepts of informal empire and collaboration are useful in analysing the relationship between Oman, Britain and the United States. The theoretical framework is the historical materialist paradigm of International Relations. State formation in Oman since 1920 is examined in a historical narrative structured by three themes: (1) the international context of Western involvement, (2) the development of Western strategic interests in Oman and (3) their economic, social and political impact on Oman. -

Retirement Planning Shortfalls the First Female Fso the Diplomat's Ethical

PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE ASSOCIATION JULY-AUGUST 2013 THE DIPLOMAT’S ETHICAL GROUNDING RETIREMENT PLANNING SHORTFALLS THE FIRST FEMALE FSO FOREIGN July-August 2013 SERVICE Volume 90, No. 7-8 FOCUS ON PROFESSIONAL ETHICS AFSA NEWS Presenting the 2013 AFSA Merit Ethics for the Professional Diplomat / 22 Award Winners / 49 A code of ethics is essential to give diplomatic practitioners guidance State VP: On Becoming Foreign with respect to personal, as well as official, boundaries. Service Policymakers / 50 Here are some components of such a code. Retiree VP: Déjà Vu All Over BY EDWARD MARKS Again / 51 2013-2015 Governing Board The Role of Dissent in National Security, Election Results/ 51 AFSA and Santa Fe Retirees Law and Conscience / 27 Sponsor Symposium / 52 One of three officers to resign from the Foreign Service a decade ago Book Notes: Living Longer, in protest of the Iraq War revisits the ethical implications of that decision. Stronger and Happier / 53 BY ANN WRIGHT 2013 AFSA Awards Winners / 53 AFSA Best Essay Winner: Some My Resignation in Retrospect / 32 Nails, Some Tape / 56 Those of us in the Foreign Service must keep our moral and professional compass PMA Funds AFSA calibrated to that point where integrity and love of country declare, “No further.” Scholarship / 56 BY JOHN BRADY KIESLING 2013 George F. Kennan Award Winner / 57 Sponsors: Supporting New Some Thoughts on Dissent / 36 Arrivals from the Get-Go / 58 All government employees should be free to speak their minds as openly FSYF 2013 Contest and Award as possible without endangering national security—a term regrettably Winners / 59 all too often used as an excuse to shut them up. -

APPOINTEE FILES: Records, 1981- 1989 – REAGAN LIBRARY COLLECTIONS

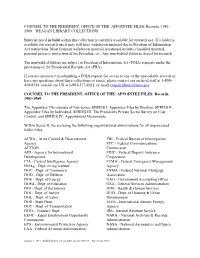

COUNSEL TO THE PRESIDENT, OFFICE OF THE: APPOINTEE FILES: Records, 1981- 1989 – REAGAN LIBRARY COLLECTIONS Material noted in bold within this collection is currently available for research use. If a folder is available for research use it may still have withdrawn material due to Freedom of Information Act restrictions. Most frequent withdrawn material is national security classified material, personal privacy, protection of the President, etc. Any non-bolded folder is closed for research. The non-bolded folders are subject to Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests under the provisions of the Presidential Records Act (PRA). If you are interested in submitting a FOIA request for access to any of the unavailable records or have any questions about these collections or series, please contact our archival staff at 1-800- 410-8354, outside the US at 1-805-577-4012, or email [email protected] COUNSEL TO THE PRESIDENT, OFFICE OF THE: APPOINTEE FILES: Records, 1981-1989 The Appointee File consists of four series: SERIES I: Appointee Files by Position; SERIES II: Appointee Files by Individual; SERIES III: The President's Private Sector Survey on Cost Control, and SERIES IV: Appointment Memoranda Within Series II, we are using the following organizational abbreviations for all unprocessed folder titles: ACDA - Arms Control & Disarmament FBI - Federal Bureau of Investigation Agency FCC - Federal Communications ACTION Commission AID - Agency for International FDIC - Federal Deposit Insurance Development Corporation CIA - Central Intelligence Agency FEMA - Federal Emergency Management DOAg - Dept. of Agriculture Agency DOC - Dept. of Commerce FNMA - Federal National Mortgage DOD - Dept. of Defense Association DOE - Dept. -

The Role of Smart Power in U.S.-Spain Relations, 1969-1986

THE ROLE OF SMART POWER IN U.S.-SPAIN RELATIONS, 1969-1986 By DAVID A. JUSTICE Bachelor of Arts in History Athens State University Athens, Alabama 2012 Master of Arts in History University of North Alabama Florence, Alabama 2014 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May, 2020 THE ROLE OF SMART POWER IN U.S.-SPAIN RELATIONS, 1969-1986 Dissertation Approved: Dr. Laura Belmonte Dissertation Adviser Dr. Douglas Miller Dr. Matthew Schauer Dr. Isabel Álvarez-Sancho ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation, this labor of love, would not be complete if it were not for a number of people. First, I would like to thank my dissertation committee of brilliant scholars. My advisor Laura Belmonte was integral in shaping this work and myself as an academic. Since my arrival at Oklahoma State, Dr. B has crafted me into the scholar that I am now. Her tireless encouragement, editing of multiple drafts, and support of this ever evolving project will always be appreciated. She also provided me with numerous laughs from the presidential pups, Willy and James. Doug Miller has championed my work since we began working together, and his candor and unconditional support was vital to finishing. Also, our discussions of Major League Baseball were much needed during coursework. Matt Schauer’s mentorship was integral to my time at Oklahoma State. The continuous laughter and support during meetings, along with discussions of classic films, were vital to my time at Oklahoma State. -

Of the AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE

SENIOR LIVING FOUNDATION of the AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE A Time of Service, A Time of Need Volume 22, Number 1 FOUNDATION NEWSLETTER March 2019 Message from the Chairman The Senior Living Foundation (SLF) of the American Foreign Service had a very active and successful year. Your financial support made it possible for SLF to meet its commitment to “taking care of our own.” Thirty years of building a strong community and changing lives has been sustained by your generous donations. In 2018, SLF received over $920,000 in donations, including a remarkable $600,000 bequest from an individual who believed in our mission during his life and wanted to help continue our work. The Foundation assists retired Foreign Service personnel and their spouses who find themselves in need. Your contributions helped defray the costs of prescription drugs, utility bills, basic living expenses, and a variety of other services. Whether SLF purchased hearing aids or provided resource information, your donation had an impact and made a difference. Beyond SLF’s assistance to those individuals in need, the Foundation hosted its 8th Planning for Change (PFC) seminar in September. The successful educational event featured twelve guest speakers with expertise in topics important to SLF’s supporters. The participants learned about senior mental health, one-on-one coaching, new tax laws, estate planning, and much more. You can read about PFC, as well as learn how to access the seminar recordings, inside this newsletter. I am saddened to report that SLF Board Member Ambassador Alan W. Lukens passed away in January 2019. He had served as a Foundation Board Member since 1999 and helped to shape both the mission and the culture of SLF.