Income Generating Opportunties Arising from Natural Ecosystems in Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conservation of Asian Honey Bees Benjamin P

Conservation of Asian honey bees Benjamin P. Oldroyd, Piyamas Nanork To cite this version: Benjamin P. Oldroyd, Piyamas Nanork. Conservation of Asian honey bees. Apidologie, Springer Verlag, 2009, 40 (3), 10.1051/apido/2009021. hal-00892024 HAL Id: hal-00892024 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00892024 Submitted on 1 Jan 2009 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Apidologie 40 (2009) 296–312 Available online at: c INRA/DIB-AGIB/EDP Sciences, 2009 www.apidologie.org DOI: 10.1051/apido/2009021 Review article Conservation of Asian honey bees* Benjamin P. Oldroyd1, Piyamas Nanork2 1 Behaviour and Genetics of Social Insects Lab, School of Biological Sciences A12, University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia 2 Department of Biology, Mahasarakham University, Mahasarakham, Thailand Received 26 June 2008 – Revised 14 October 2008 – Accepted 29 October 2008 Abstract – East Asia is home to at least 9 indigenous species of honey bee. These bees are extremely valu- able because they are key pollinators of about 1/3 of crop species, provide significant income to some of the world’s poorest people, and are prey items for some endemic vertebrates. -

Gender and Non-Timber Forest Products

Gender and non-timber forest products Promoting food security and economic empowerment Marilyn Carr, international consultant on gender, technology, rural enterprise and poverty reduction, prepared this paper in collaboration with Maria Hartl, technical adviser for gender and social equity in the IFAD Technical Advisory Division. Other staff members of the IFAD Technical Advisory Division contributing to the paper included: Annina Lubbock, senior technical adviser for gender and poverty targeting, Sheila Mwanundu, senior technical adviser for environment and natural resource management, and Ilaria Firmian, associate technical adviser for environment and natural resource management. The following people reviewed the content: Rama Rao and Bhargavi Motukuri (International Network for Bamboo and Rattan), Kate Schreckenberg (Overseas Development Institute), Nazneen Kanji (Aga Khan Development Network), Sophie Grouwels (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) and Stephen Biggs (School of Development Studies, University of East Anglia). The opinions expressed in this book are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IFAD concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The designations ‘developed’ and ‘developing’ countries are intended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgement about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the development process. Cover: Women make panels and carpets from braided coconut leaves at this production unit near Naickenkottai, India. -

Tar and Turpentine

ECONOMICHISTORY Tar and Turpentine BY BETTY JOYCE NASH Tarheels extract the South’s first industry turdy, towering, and fire-resistant longleaf pine trees covered 90 million coastal acres in colonial times, Sstretching some 150,000 square miles from Norfolk, Va., to Florida, and west along the Gulf Coast to Texas. Four hundred years later, a scant 3 percent of what was known as “the great piney woods” remains. The trees’ abundance grew the Southeast’s first major industry, one that served the world’s biggest fleet, the British Navy, with the naval stores essential to shipbuilding and maintenance. The pines yielded gum resin, rosin, pitch, tar, and turpentine. On oceangoing ships, pitch and tar Wilmington, N.C., was a hub for the naval stores industry. caulked seams, plugged leaks, and preserved ropes and This photograph depicts barrels at the Worth and Worth rosin yard and landing in 1873. rigging so they wouldn’t rot in the salty air. Nations depended on these goods. “Without them, and barrels in 1698. To stimulate naval stores production, in 1704 without access to the forests from which they came, a Britain offered the colonies an incentive, known as a bounty. nation’s military and commercial fleets were useless and its Parliament’s “Act for Encouraging the Importation of Naval ambitions fruitless,” author Lawrence Earley notes in his Stores from America” helped defray the eight-pounds- book Looking for Longleaf: The Rise and Fall of an American per-ton shipping cost at a rate of four pounds a ton on tar Forest. and pitch and three pounds on rosin and turpentine. -

DPR Journal 2016 Corrected Final.Pmd

Bul. Dept. Pl. Res. No. 38 (A Scientific Publication) Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation Department of Plant Resources Thapathali, Kathmandu, Nepal 2016 ISSN 1995 - 8579 Bulletin of Department of Plant Resources No. 38 PLANT RESOURCES Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation Department of Plant Resources Thapathali, Kathmandu, Nepal 2016 Advisory Board Mr. Rajdev Prasad Yadav Ms. Sushma Upadhyaya Mr. Sanjeev Kumar Rai Managing Editor Sudhita Basukala Editorial Board Prof. Dr. Dharma Raj Dangol Dr. Nirmala Joshi Ms. Keshari Maiya Rajkarnikar Ms. Jyoti Joshi Bhatta Ms. Usha Tandukar Ms. Shiwani Khadgi Mr. Laxman Jha Ms. Ribita Tamrakar No. of Copies: 500 Cover Photo: Hypericum cordifolium and Bistorta milletioides (Dr. Keshab Raj Rajbhandari) Silene helleboriflora (Ganga Datt Bhatt), Potentilla makaluensis (Dr. Hiroshi Ikeda) Date of Publication: April 2016 © All rights reserved Department of Plant Resources (DPR) Thapathali, Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: 977-1-4251160, 4251161, 4268246 E-mail: [email protected] Citation: Name of the author, year of publication. Title of the paper, Bul. Dept. Pl. Res. N. 38, N. of pages, Department of Plant Resources, Kathmandu, Nepal. ISSN: 1995-8579 Published By: Mr. B.K. Khakurel Publicity and Documentation Section Dr. K.R. Bhattarai Department of Plant Resources (DPR), Kathmandu,Ms. N. Nepal. Joshi Dr. M.N. Subedi Reviewers: Dr. Anjana Singh Ms. Jyoti Joshi Bhatt Prof. Dr. Ram Prashad Chaudhary Mr. Baidhya Nath Mahato Dr. Keshab Raj Rajbhandari Ms. Rose Shrestha Dr. Bijaya Pant Dr. Krishna Kumar Shrestha Ms. Shushma Upadhyaya Dr. Bharat Babu Shrestha Dr. Mahesh Kumar Adhikari Dr. Sundar Man Shrestha Dr. -

Beekeeping and Sustainable Livelihoods

ISSN 1810-0775 Beekeeping and sustainable livelihoods Second edition )$2'LYHUVLÀFDWLRQERRNOHW Diversification booklet number 1 Second edition Beekeeping and sustainable livelihoods Martin Hilmi, Nicola Bradbear and Danilo Mejia Rural Infrastructure and Agro-Industries Division Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome 2011 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO. ISBN 978-92-5-107062-8 All rights reserved. FAO encourages reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Non-commercial uses will be authorized free of charge, upon request. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes, including educational purposes, may incur fees. Applications for permission to reproduce or disseminate FAO copyright materials, and all queries concerning rights and licences, should be addressed by e-mail to [email protected] or to the Chief, Publishing Policy and Support Branch, Office of Knowledge Exchange, Research and Extension, FAO, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00153 Rome, Italy. -

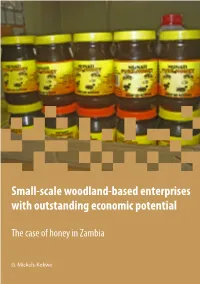

The Case of Honey in Zambia the Case

Small-scale with outstanding economic potential enterprises woodland-based In some countries, honey and beeswax are so important the term ‘beekeeping’ appears in the titles of some government ministries. The significance of honey and beeswax in local livelihoods is nowhere more apparent than in the Miombo woodlands of southern Africa. Bee-keeping is a vital source of income for many poor and remote rural producers throughout the Miombo, often because it is highly suited to small scale farming. This detailed Non-Timber Forest Product study from Zambia examines beekeeping’s livelihood role from a range of perspectives, including market factors, production methods and measures for harnessing beekeeping to help reduce poverty. The caseThe in Zambia of honey ISBN 979-24-4673-7 Small-scale woodland-based enterprises with outstanding economic potential 9 789792 446739 The case of honey in Zambia G. Mickels-Kokwe G. Mickels-Kokwe Small-scale woodland-based enterprises with outstanding economic potential The case of honey in Zambia G. Mickels-Kokwe National Library of Indonesia Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mickels-Kokwe, G. Small-scale woodland-based enterprises with outstanding economic potential: the case of honey in Zambia/by G. Mickels-Kokwe. Bogor, Indonesia: Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), 2006. ISBN 979-24-4673-7 82p. CABI thesaurus: 1. small businesses 2. honey 3. beekeeping 4. commercial beekeeping 5. non- timber forest products 6. production 7. processing 8. trade 9.government policy 10. woodlands 11. case studies 12. Zambia I. Title © 2006 by CIFOR All rights reserved. Published in 2006 Printed by Subur Printing, Jakarta Design and Layout by Catur Wahyu and Eko Prianto Cover photo by Mercy Mwape of the Forestry Department of Zambia Published by Center for International Forestry Research Jl. -

Eastern Himalayas

JANUARY 2013 Eastern Himalayas A quarterly newsletter of the ATREE Eastern Himalayas / Northeast India Programme VOLUME 1, ISSUE 3 © Urbashi© Pradhan/ATREE The old man and the bees “I would get irritated by the buzzing of bees visiting the orange orchard during flowering season. It was unbearable!” recalls Pratap baje (grandfather), sipping his tea on a cold winter morning. “So many bees…so many different kinds! This whole valley would smell so good with the aroma of orange flowers. It was as if someone had sprayed some perfume!” The old farmer in his 80s was my host in the village I asked him about bees in the wild and he recalled of Zoom, Sikkim. Memories seemed to flash across the days when he would go honey hunting with his wrinkled face as he spoke. “I had three hives friends in the dense forest patches nearby. “If you and they would be full of honey this season. One go now you will not even find a dead bee. A bottle was attacked by a malsapro (yellow-throated of honey costs five hundred rupees today. marten).” He then pointed to an ageing orange Everything is gone," he says in a resigned manner. tree. “In 1974 (confirms the year with his wife) this He thinks the use of pesticides killed both harmful very tree yielded 5218 fruits. We sat and counted and useful insects and that there is no food for bees each one of them. Now even a mature tree does in the wild because the forests have been cleared. not yield more than 1500. -

An Abstract of the Thesis Of

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Brenda M Kellar for the degree of Master of Arts in Applied Anthropology presented on May 4. 2004. Title: One Methodology for the Incorporation of Entomological Material in the Discipline of Historic Archaeology Using the Honey Bee (Apis mellifera L.) as a Test Subject. Abstract approved:. Redacted for Privacy David R. Brauner Using the honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) this thesis shows that entomological information and material can be retrieved using current historical archaeological methods. Historical archaeology has the ability to uncover connections between arenas as varied, and seemingly isolated, as the honey bee, the environment, and human cultures. By focusing on one of these arenas, the honey bee in this thesis, we can learn about the forces that drive change within all these arenas. Additionally, historical archaeology can help us to trace the affects of change outside the source, so that a change in the honey bee population is understood to affect both human cultures and the environment. © Copyright by Brenda M Kellar May 4, 2004 All Rights Reserved One Methodology for the Incorporation of Entomological Material in the Discipline of Historic Archaeology Using the Honey Bee (ApismellferaL.) as a Test Subject. By Brenda M Kellar A THESIS Submitted to Oregon State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Presented May 4, 2004 Commencement June 2005 Master of Arts thesis of Brenda M Kellar presented on May 4. 2004. APPROVED: Redacted for Privacy Major Professor, representing Applied Anthropology Redacted for Privacy Chair of the Department of Anthropology Redacted for Privacy Deanof the Gdduat School I understand that my thesis will become part of the permanent collection of Oregon State University libraries. -

Pine Tar; History and Uses

Pine Tar; History And Uses Theodore P. Kaye Few visitors to any ship which as been rigged in a traditional manner have left the vessel without experiencing the aroma of pine tar. The aroma produces reactions that are as strong as the scent; few people are ambivalent about its distinctive smell. As professionals engaged in the restoration and maintenance of old ships, we should know not only about this product, but also some of its history. Wood tar has been used by mariners as a preservative for wood and rigging for at least the past six centuries. In the northern parts of Scandinavia, small land owners produced wood tar as a cash crop. This tar was traded for staples and made its way to larger towns and cities for further distribution. In Sweden, it was called "Peasant Tar" or was named for the district from which it came, for example, Lukea Tar or Umea Tar. At first barrels were exported directly from the regions in which they were produced with the region's name burned into the barrel. These regional tars varied in quality and in the type of barrel used to transport it to market. Wood tars from Finland and Russia were seen as inferior to even the lowest grade of Swedish tar which was Haparanda tar. In 1648, the newly formed NorrlSndska TjSrkompaniet (The Wood Tar Company of North Sweden) was granted sole export privileges for the country by the King of Sweden. As Stockholm grew in importance, pine tar trading concentrated at this port and all the barrels were marked "Stockholm Tar". -

Comb the Honey: Bee Interface Design by Ri Ren

Comb the Honey: Bee Interface Design by Ri Ren Ph.D., Central Academy of Fine Arts (2014) S.M., Saint-Petersburg Herzen State University (2010) B.A.,Tsinghua University (2007) Submitted to the Program in Media Arts and Sciences, School of Architecture and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Media Arts and Sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology May 2020 © Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2020. All rights reserved. Author ………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Program in Media Arts and Sciences May 2020 Certified by ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Neri Oxman Associate Professor of Media Arts and Sciences Accepted by ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Tod Machover Academic Head, Program in Media Arts and Sciences 2 Comb the Honey: Bee Interface Design by Ri Ren Submitted to the Program in Media Arts and Sciences, School of Architecture and Planning on May 2020 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Media Arts and Sciences Abstract: The overarching goal of the thesis is to understand the mechanisms by which complex forms are created in biological systems and how the external environment and factors can influence generations over different scales of space, time, and materials. My research focuses on Nature’s most celebrated architects — bees — and their architectural masterpiece — the honeycomb. Bee honeycombs are wax-made cellular structures of hexagonal prismatic geometries. Within the comb, bees form their nests, grow their larvae, and store honey and pollen. They operate as a “social womb” informed, at once, by communal (genetic) makeup and environmental forces. Resource sharing, labor division, and unique communication methods all contribute to the magic that is the bee “Utopia.” Given that the geometrical, structural, and material make up of honeycombs is informed by the environment, these structures act as environmental footprints, revealing, as a time capsule, the history of its external environment and factors. -

MDBA Newsletter

FEBRUARY 2008 2008 BOARD HIGHLIGHTS OF THIS ISSUE www.diablobees.org President *********************** Rick Kautch First Vice President What’s the Buzz?........................... 1 Tom Lewis General Meeting (925) 348-4470 Announcements………………….. 1 Past President Our next meeting is February 14 at Stan Thomas The Tualang Tree..……................ 2 7:30 pm at the Heather Farm Garden VP-Community Education Newbee Nuggets ...………………. Center in Walnut Creek. 5 Judy Casale (510) 881-4939 Recipe of the Month ….………..... 6 [email protected] *********************** VP-Member Education Richard Coleman 925 685-6849 Announcements [email protected] ****************************** Treasurer Please send interesting bee Jeff Peacock articles via email to: 925-284-9389 [email protected] [email protected] What’s Secretary Lois Kail the Buzz? ****************************** Membership Dues Membership Kim Coleman 925 685-6849 Your $15 yearly dues should be sent to: [email protected] Jeff Peacock, Treasurer Newsletter Mount Diablo Beekeepers Association Ersten Imaoka 3341 Walnut Lane 925-687-7350 Lafayette, CA 94549 [email protected] . Or…. you can give Jeff your check at any monthly meeting. Next meeting: ****************************** 7:30 pm – 02/14/08 Much thanks to Dr. Gordon Frankie of If you have an active email address, Heather Farm Garden U.C. Berkeley for his captivating you will receive this newsletter by e- Center presentation on California native bees mail unless you inform Kim 1540 Marchbanks and their habitat. Who knew, prior to Walnut Creek Coleman at: his talk, that our state was the home of [email protected] upwards of 1600 species of native bees?!?! that you wish to receive a hard copy. 2 The Diablo Bee – February 2008 Here, humans had learned to face the magical The Tualang Tree, the Giant Asian Honey ferocity of social bees with their own magic, as they have done for millennia. -

Gum Naval Stores: Turpentine and Rosin from Pine Resin

- z NON-WOOD FORESTFOREST PRODUCTSPRODUCTS ~-> 2 Gum naval stores:stores: turpentine and rosinrosin from pinepine resinresin Food and Agriculture Organization of the Unaed Nations N\O\ON- -WOODWOOD FOREST FOREST PRODUCTSPRODUCTS 22 Gum navalnaval stores:stores: turpentine• and rosinrosin from pinepine resinresin J.J.W.J.J.W. Coppen andand G.A.G.A. HoneHone Mi(Mf' NANATURALTURAL RESRESOURCESOURCES INSTITUTEIN STITUTE FFOODOOD ANDAN D AGRICULTUREAGRIC ULTURE ORGANIZATIONORGANIZATION OFOF THETH E UNITEDUNITED NATIONSNATIONS Rome,Rome, 19951995 The designationsdesignations employedemployed andand thethe presentationpresentation of of materialmaterial inin thisthis publication do not imply the expression of any opinionopinion whatsoever onon thethe partpart ofof thethe FoodFood andand AgricultureAgriculture OrganizationOrganization ofof thethe UnitedUnited Nations concernconcerninging thethe legal status of any countrycountry,, territory, city or areaareaorofits or of its auauthorities,thorities, orconcerningor concerning the delimitationdelirnitation of itsits frontiers or boundaries.boundaries. M-37M-37 IISBNSBN 92-5-103684-5 AAllll rights reserved.reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrretrievalieval systemsystem,, oror transmitted inin any form or byby anyany means,means, electronic,electronic, mechanimechanicai,cal, photocphotocopyingopying oror otherwise, withoutwithout thethe prior permission ofof the copyright owner. AppApplicationslications forfor such permission,permission, with a statementstatement