A Public Voice – AHRC/BBC Knowledge Exchange Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lake Forest College Catalog 555 North Sheridan Road • Lake Forest, Illinois 60045 • 847-234-3100 2019-2020

Lake Forest College Catalog 555 North Sheridan Road • Lake Forest, Illinois 60045 • 847-234-3100 2019-2020 This pdf document represents an archived version of the 2019–20 online College Catalog. Information is accurate as of August 1, 2019. For the most up-to-date version of the College Catalog, please consult the online version at lakeforest.edu/academics/catalog TABLE OF CONTENTS General Information ...........................................................................................................................................................................................1 Mission Statement .........................................................................................................................................................................................1 Non-Discrimination Policy ........................................................................................................................................................................1 Privacy Statement ..........................................................................................................................................................................................2 Family Educational Rights Privacy Act ...............................................................................................................................................2 Academic Calendar .............................................................................................................................................................................................3 -

Afrocentrism Through Afro-American Music: from the 1960’S Until the Early 2000’S

Afrocentrism through Afro-American Music: from the 1960’s until the Early 2000’s by Jérémie Kroubo Dagnini, Department of Anglophone Studies University Michel de Montaigne Bordeaux 3, France. Jérémie Kroubo Dagnini ([email protected]) is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Anglophone Studies at the University Michel de Montaigne Bordeaux 3 in France, conducting research on the history of Jamaican popular music in the twentieth century. He is the author of Les origines du reggae: retour aux sources. Mento, ska, rocksteady, early reggae published by L’Harmattan in 2008. Abstract Afrocentrism is an intellectual, political, sociological, historical and cultural movement principally born out of Black people’s constant struggle against racism and oppression. Thus, this ideology dates back to the era of slavery and was born in the Black diaspora as a response to Eurocentrism which views the world from a European perspective, implying superiority of Europeans and more generally Westerners, namely Whites, over non-Europeans, namely non- Whites, especially Blacks. The United States of America being an ancient land of slavery, it is not surprising that Afrocentrism emerged within its society. It has been notably significant from the late 19th onwards and has impacted on different aspects of social life, including literature, politics, religion, economy, sport and music. Since the 1960’s, Afrocentrism has been particularly visible through music which has become an obvious new force in America. Indeed, in the 1960’s, it was an integral part of soul music which accompanied the civil rights movements. Then, it has integrated most genres which followed up such as funk, rap and modern rhythm and blues. -

Daryl Lowery Sample Songlist Bridal Songs

DARYL LOWERY SAMPLE SONGLIST BRIDAL SONGS Song Title Artist/Group Always And Forever Heatwave All My Life K-Ci & Jo JO Amazed Lonestar At Last Etta James Because You Loved Me Celine Dion Breathe Faith Hill Can't Help Falling In Love Elvis Presley Come Away With Me Nora Jones Could I Have This Dance Anne Murray Endless Love Lionel Ritchie & Diana Ross (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Bryan Adams From This Moment On Shania Twain & Brian White Have I Told You Lately Rod Stewart Here And Now Luther Van Dross Here, There And Everywhere Beatles I Could Not Ask For More Edwin McCain I Cross My Heart George Strait I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees I Don't Want To Miss A Thing Aerosmith I Knew I Loved You Savage Garden I'll Always Love You Taylor Dane In Your Eyes Peter Gabriel Just The Way You Are Billy Joel Keeper Of The Stars Tracy Byrd Making Memories Of Us Keith Urban More Than Words Extreme One Wish Ray J Open Arms Journey Ribbon In The Sky Stevie Wonder Someone Like You Van Morrison Thank You Dido That's Amore Dean Martin The Way You Look Tonight Frank Sinatra The Wind Beneath My Wings Bette Midler Unchained Melody Righteous Brothers What A Wonderful World Louis Armstrong When A Man Loves A Woman Percy Sledge Wonderful Tonight Eric Clapton You And Me Lifehouse You're The Inspiration Chicago Your Song Elton John MOTHER/SON DANCE Song Title Artist/Group A Song For Mama Boyz II Men A Song For My Son Mikki Viereck You Raise Me Up Josh Groban Wind Beneath My Wings Bette Midler FATHER/DAUGHTER DANCE Song Title Artist/Group Because You Loved Me Celine Dion Butterfly Kisses Bob Carlisle Daddy's Little Girl Mills Brothers Unforgettable Nat & Natalie King Cole What A Wonderful World Louis Armstrong Popular Selections: "Big Band” To "Hip Hop" Song Title Artist/Group (Oh What A Night) December 1963 Four Seasons 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 1985 Bowling For Soup 1999 Prince 21 Questions 50 Cent 867-5309 Tommy Tutone A New Day Has Come Celine Dion A Song For My Son Mikki Viereck A Thousand Years Christine Perri A Wink And A Smile Harry Connick, Jr. -

Child from Treichville

The "terrible" child from Treichville Musical lives in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire Bente E. Aster Hovedfagsoppgave i sosialantropologi Høst 2004. Universitetet i Oslo Summary In this thesis I investigate modern music genres and performance practices in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. I worked with three band structures, within three different genres: The local pop genre zouglou, the dancehall genre and the reggae genre. I have especially concentrated on reggae, and I compare how it is played and performed in Côte d’Ivoire to how it is perceived in Jamaica. Interestingly enough, reggae sounds different in the two countries, and in my thesis I hope to show the various reasons for this phenomenon. I am interested in the questions: Why do Ivorians listen to reggae, and what do they do in order to adapt it to the Ivorian setting? I claim that a certain social environment produces certain aesthetical preferences and performance practices. In short it produces taste: History and taste go together. Thus styles are historically constructed identity marks. Christopher Waterman has linked various social histories to musical genres and tastes in Nigeria in interesting ways (Waterman 1990). The Ivorian setting creates a sound that is denser and involves a heavier orchestration than the Jamaican one, which is cut down to the core. The two countries have different points of departure and different histories, and one can hear the traces of this in the two versions of reggae. Global inspirations become local expressions to Ivorians. Singers must uphold their local credibility and authenticity, and thereby create a resonance between themselves and their audience. -

Religion, Nationalism, and Everyday Performance in Congo

GESTURE AND POWER The Religious Cultures of African and African Diaspora People Series editors: Jacob K. Olupona, Harvard University Dianne M. Stewart, Emory University and Terrence L. Johnson, Georgetown University The book series examines the religious, cultural, and political expres- sions of African, African American, and African Caribbean traditions. Through transnational, cross- cultural, and multidisciplinary approaches to the study of religion, the series investigates the epistemic boundaries of continental and diasporic religious practices and thought and explores the diverse and distinct ways African- derived religions inform culture and politics. The series aims to establish a forum for imagining the centrality of Black religions in the formation of the “New World.” GESTURE AND POWER Religion, Nationalism, and Everyday Performance in Congo Yolanda Covington- Ward Duke University Press Durham and London 2016 © 2016 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Typeset in Minion Pro and Avenir by Graphic Composition, Inc., Bogart, Georgia Library of Congress Cataloging- in-Publication Data Covington-Ward, Yolanda, [date] author. Gesture and power : religion, nationalism, and everyday performance in Congo / Yolanda Covington-Ward. pages cm—(The religious cultures of African and African diaspora people) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-0-8223-6020-9 (hardcover: alk. paper) isbn 978-0-8223-6036-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn 978-0-8223-7484-8 (e-book) 1. Kongo (African people)—Communication. 2. Body language—Congo (Democratic Republic) 3. Dance—Social aspects—Congo (Democratic Republic) I. Title. II. Series: Religious cultures of African and African diaspora people. 394—dc23 2015020742 Cover art: Weighing of the spirit (bascule) in worship service, dmna Church, Luozi, 2010. -

Island Thinking Suffolk Stories of Landscape, Militarisation and Identity Sophia Davis Island Thinking

Island Thinking Suffolk Stories of Landscape, Militarisation and Identity Sophia Davis Island Thinking “In this thoughtful and illuminating book, Sophia Davis asks us to consider the imaginative appeal of what it means to be an island. Taking in the view from the shores of the Sufolk coast, Island Tinking looks at how ideas of nationhood, identity, defence and nature become bound together in place. Tis book uncovers the stories of how this small, seemingly isolated part of England became signifcant to emerging national narratives about Englishness, its rural inheritance and its future military technological prowess.” —Rachel Woodward, Professor of Human Geography, School of Geography, Politics & Sociology, Newcastle University, UK, and author of Military Geographies “Sophia Davis’s Island Tinking ofers a fascinating and compelling account of mid-twentieth-century Englishness, as seen through a rich archipelagic history of one of England’s most peculiar and most iconic counties, Sufolk. Davis leads the reader through the intensely local impacts and afects of profound historical and global change, and reads the landscape wisely and well for what it can tell us about the dramatic transformations of English culture through and after the Second World War.” —Professor John Brannigan, University College Dublin, and author of Archipelagic Modernism: Literature in the Irish and British Isles, 1890–1970 “Trough close scrutiny of Sufolk stories, Sophia Davis ofers a compelling narrative of islandness in England from the mid-twentieth century. Tese accounts of landscape and militarisation, migration and the natural world, show how island thinking invokes both refuge and anxiety, security and fear. In looking back, Island Tinking captures ongoing English preoccupations.” —David Matless, Professor of Cultural Geography, University of Nottingham, and author of In the Nature of Landscape “Island Tinking expertly takes the reader into the secrets of the Sufolk coun- tryside in a way that no other study has. -

City of Angels

ZANFAGNA CHRISTINA ZANFAGNA | HOLY HIP HOP IN THE CITY OF ANGELSHOLY IN THE CITY OF ANGELS The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous support of the Lisa See Endowment Fund in Southern California History and Culture of the University of California Press Foundation. Luminos is the Open Access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and reinvigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org Holy Hip Hop in the City of Angels MUSIC OF THE AFRICAN DIASPORA Shana Redmond, Editor Guthrie P. Ramsey, Jr., Editor 1. California Soul: Music of African Americans in the West, edited by Jacqueline Cogdell DjeDje and Eddie S. Meadows 2. William Grant Still: A Study in Contradictions, by Catherine Parsons Smith 3. Jazz on the Road: Don Albert’s Musical Life, by Christopher Wilkinson 4. Harlem in Montmartre: A Paris Jazz Story between the Great Wars, by William A. Shack 5. Dead Man Blues: Jelly Roll Morton Way Out West, by Phil Pastras 6. What Is This Thing Called Jazz?: African American Musicians as Artists, Critics, and Activists, by Eric Porter 7. Race Music: Black Cultures from Bebop to Hip-Hop, by Guthrie P. Ramsey, Jr. 8. Lining Out the Word: Dr. Watts Hymn Singing in the Music of Black Americans, by William T. Dargan 9. Music and Revolution: Cultural Change in Socialist Cuba, by Robin D. -

Adroddiad Blynyddol / Annual Report 1996-97

ADRODDIAD BLYNYDDOL / ANNUAL REPORT 1996-97 Colin Edwards Papers 1997001 Ffynhonnell / Source The late Mr Colin D Edwards, California, USA Blwyddyn / Year Adroddiad Blynyddol / Annual Report 1996-97 Disgrifiad / Description / Description Papers of Colin Edwards (d 1994), a radio journalist of Welsh descent, comprising typescript chapters of his incomplete book on Dylan Thomas. Douglas B Hague Research Papers 1997002 Ffynhonnell / Source The late Mr Douglas B Hague, Llanafan Blwyddyn / Year Adroddiad Blynyddol / Annual Report 1996-97 Disgrifiad / Description / Description Research papers of Douglas B Hague (1917-90) comprising papers relating to the volumes Lighthouses: Their Architecture, History and Archaeology (Llandysul, 1975), co-written with Rosemary Christie, and Lighthouses of Wales (Aberystwyth, 1994). NLW MSS 15282-3; NLW ex 1763 1997003 Ffynhonnell / Source The late Mrs Effie Isaura Hughes, Pwllheli Blwyddyn / Year Adroddiad Blynyddol / Annual Report 1996-97 Disgrifiad / Description / Description The final typescript of 'In the Springtime of Song', the unpublished autobiography, dated 1946-7, of the testator's mother the singer Leila Megane (Margaret/Maggie Jones, 1891-1960) (see Annual Report 1979-80, p 63), together with related letters and papers, 1934-7 (NLW MSS 15282-3); and a typescript copy, with autograph revision, of the work (NLW ex 1763). NLW MS 23559E 1997004 Ffynhonnell / Source The late Professor Stuart Piggott, Wantage, Oxfordshire Blwyddyn / Year Adroddiad Blynyddol / Annual Report 1996-97 Disgrifiad / Description / Description Nine letters and one card, 1953-67, from David Jones (1895-1974), artist and writer, to Stuart Piggott (1910-96), Abercromby Professor of Prehistoric Archaeology, University of Edinburgh, 1946-77; and a photocopy of a journal entry by the testator, 16 June 1967, describing a visit to David Jones. -

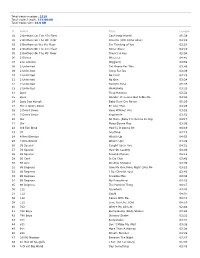

Total Tracks Number: 2218 Total Tracks Length: 151:00:00 Total Tracks Size: 16.0 GB

Total tracks number: 2218 Total tracks length: 151:00:00 Total tracks size: 16.0 GB # Artist Title Length 01 2 Brothers On The 4Th Floor Can't Help Myself 05:39 02 2 Brothers On The 4th Floor Dreams (Will Come Alive) 04:19 03 2 Brothers on the 4th Floor I'm Thinking of You 03:24 04 2 Brothers On The 4Th Floor Never Alone 04:10 05 2 Brothers On The 4th Floor There's A Key 03:54 06 2 Eivissa Oh La La 04:41 07 2 In a Room Wiggle It 03:59 08 2 Unlimited Get Ready For This 03:40 09 2 Unlimited Jump For Joy 03:39 10 2 Unlimited No Limit 03:28 11 2 Unlimited No One 03:24 12 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 05:36 13 2 Unlimited Workaholic 03:33 14 2pac Thug Mansion 03:32 15 2pac Wonder If Heaven Got A Ghetto 04:34 16 2pac Daz Kurupt Baby Dont Cry Remix 05:20 17 Three Doors Down Be Like That 04:25 18 3 Doors Down Here Without You 03:53 19 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 03:52 20 3lw No More (Baby I'm Gonna Do Rig 04:17 21 3lw Playa Gonna Play 03:06 22 3rd Eye Blind How Is It Gonna Be 04:10 23 3T Anything 04:15 24 4 Non Blondes What's Up 04:55 25 4 Non Blonds What's Up? 04:09 26 38 Special Caught Up In You 04:25 27 38 Special Hold On Loosely 04:40 28 38 Special Second Chance 04:12 29 50 Cent In Da Club 03:42 30 50 cent Window Shopper 03:09 31 98 Degrees Give Me One More Night (Una No 03:23 32 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 03:43 33 98 Degrees Invisible Man 04:38 34 98 Degrees My Everything 04:28 35 98 Degrees The Hardest Thing 04:27 36 112 Anywhere 04:03 37 112 Cupid 04:07 38 112 Dance With Me 03:41 39 112 Love You Like I Did 04:16 40 702 Where My Girls At 02:44 -

Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums

23 May 1993 CHART #860 Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums Informer Born To Breed Breathless The Mutton Birds 1 Snow 21 Monie Love 1 Kenny G 21 The Mutton Birds Last week 1 / 9 weeks WARNER Last week 32 / 2 weeks EMI Last week 1 / 18 weeks Platinum / BMG Last week 27 / 34 weeks Gold / VIRGIN Give In To Me Hat 2 Da Back Unplugged Black Tie White Noise 2 Michael Jackson 22 TLC 2 Eric Clapton 22 David Bowie Last week 4 / 9 weeks SONY Last week 26 / 7 weeks BMG Last week 2 / 35 weeks Platinum / WARNER Last week 14 / 4 weeks BMG Are You Gonna Go My Way Seven Waters Dangerous Duophonic 3 Lenny Kravitz 23 Annie Crummer 3 Michael Jackson 23 Charles & Eddie Last week 3 / 9 weeks VIRGIN Last week 20 / 4 weeks WARNER Last week 5 / 54 weeks Platinum / SONY Last week 13 / 13 weeks EMI Two Princes Who's Lovin' You Are You Gonna Go My Way San Francisco Days 4 Spin Doctors 24 Jackson 5 4 Lenny Kravitz 24 Chris Isaak Last week 12 / 2 weeks SONY Last week 18 / 6 weeks POLYGRAM Last week 3 / 5 weeks Gold / VIRGIN Last week 18 / 4 weeks WARNER Tap The Bottle Detachable Penis Pure Cult Deep Forest 5 Young Black Teenagers 25 King Missile 5 The Cult 25 Deep Forest Last week 6 / 12 weeks BMG Last week 38 / 2 weeks WARNER Last week 4 / 7 weeks Gold / BMG Last week 31 / 9 weeks SONY Easy Livin' On The Edge Angel Dust The Jacksons: An American Dream 6 Faith No More 26 Aerosmith 6 Faith No More 26 The Jacksons Last week 14 / 9 weeks FESTIVAL Last week 16 / 4 weeks BMG Last week 28 / 13 weeks FESTIVAL Last week 16 / 7 weeks POLYGRAM Jamaican In New York Little Miss Can't Be Wrong 3 Years, 5 Months & 2 Days In The Li.. -

Keyfinder V2 Dataset © Ibrahim Sha'ath 2014

KeyFinder v2 dataset © Ibrahim Sha'ath 2014 ARTIST TITLE KEY 10CC Dreadlock Holiday Gm 187 Lockdown Gunman (Natural Born Chillers Remix) Ebm 4hero Star Chasers (Masters At Work Main Mix) Am 50 Cent In Da Club C#m 808 State Pacifc State Ebm A Guy Called Gerald Voodoo Ray A A Tribe Called Quest Can I Kick It? (Boilerhouse Mix) Em A Tribe Called Quest Find A Way Ebm A Tribe Called Quest Vivrant Thing (feat Violator) Bbm A-Skillz Drop The Funk Em Aaliyah Are You That Somebody? Dm AC-DC Back In Black Em AC-DC You Shook Me All Night Long G Acid District Keep On Searching G#m Adam F Aromatherapy (Edit) Am Adam F Circles (Album Edit) Dm Adam F Dirty Harry's Revenge (feat Beenie Man and Siamese) G#m Adam F Metropolis Fm Adam F Smash Sumthin (feat Redman) Cm Adam F Stand Clear (feat M.O.P.) (Origin Unknown Remix) F#m Adam F Where's My (feat Lil' Mo) Fm Adam K & Soha Question Gm Adamski Killer (feat Seal) Bbm Adana Twins Anymore (Manik Remix) Ebm Afrika Bambaataa Mind Control (The Danmass Instrumental) Ebm Agent Sumo Mayhem Fm Air Sexy Boy Dm Aktarv8r Afterwrath Am Aktarv8r Shinkirou A Alexis Raphael Kitchens & Bedrooms Fm Algol Callisto's Warm Oceans Am Alison Limerick Where Love Lives (Original 7" Radio Edit) Em Alix Perez Forsaken (feat Peven Everett and Spectrasoul) Cm Alphabet Pony Atoms Em Alphabet Pony Clones Am Alter Ego Rocker Am Althea & Donna Uptown Top Ranking (2001 digital remaster) Am Alton Ellis Black Man's Pride F Aluna George Your Drums, Your Love (Duke Dumont Remix) G# Amerie 1 Thing Ebm Amira My Desire (Dreem Teem Remix) Fm Amirali -

The Use of Contracted Forms in the Hip Hop Song Lyrics

THE USE OF CONTRACTED FORMS IN THE HIP HOP SONG LYRICS AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By AGUSTINA IKE WIRANTARI Student Number: 034214130 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2008 i A Sarjana Sastra Undergraduate Thesis ii THE USE OF CONTRACTED FORMS IN THE HIP HOP SONG LYRICS By AGUSTINA IKE WIRANTARI Student Number: 034214130 Defended before the Board of Examiners on January 21, 2008 and Declared Acceptable BOARD OF EXAMINERS Name Signature Chairman : Secretary : Member : Member : Member : ii iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to address all my thanks and praise to God for all His kindness, love, patience and etc. I feel that I just nothing compared with His Greatness. He is always accompanying me and giving me power to face all the obstacles in front of me. I owe so much thanks to my advisor Dr. Fr. B. Alip, M.Pd., M.A., for all his advise so I can finish my thesis, and also for my co-advisor Dr.B.Ria Lestari, M.S. for her ideas and supports in making my thesis. Thanking is also given for Ms. Sri Mulyani, for her ideas and the sources that can support my thesis, and for all the English Letters Department staffs for all their help in our study. I would never forget to address my gratitude, love, and thanks for all the supports to my family especially for my Dad, I Ketut S.W., my Mom, Lestari, and my lovely sister, Putri.