Christian Morals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Valerius Maximus on Vice: a Commentary of Facta Et Dicta

Valerius Maximus on Vice: A Commentary on Facta et Dicta Memorabilia 9.1-11 Jeffrey Murray University of Cape Town Thesis Presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in the School of Languages and Literatures University of Cape Town June 2016 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Abstract The Facta et Dicta Memorabilia of Valerius Maximus, written during the formative stages of the Roman imperial system, survives as a near unique instance of an entire work composed in the genre of Latin exemplary literature. By providing the first detailed historical and historiographical commentary on Book 9 of this prose text – a section of the work dealing principally with vice and immorality – this thesis examines how an author employs material predominantly from the earlier, Republican, period in order to validate the value system which the Romans believed was the basis of their world domination and to justify the reign of the Julio-Claudian family. By detailed analysis of the sources of Valerius’ material, of the way he transforms it within his chosen genre, and of how he frames his exempla, this thesis illuminates the contribution of an often overlooked author to the historiography of the Roman Empire. -

ROMAN ARCHITEXTURE: the IDEA of the MONUMENT in the ROMAN IMAGINATION of the AUGUSTAN AGE by Nicholas James Geller a Dissertatio

ROMAN ARCHITEXTURE: THE IDEA OF THE MONUMENT IN THE ROMAN IMAGINATION OF THE AUGUSTAN AGE by Nicholas James Geller A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Basil J. Dufallo, Chair Associate Professor Ruth Rothaus Caston Professor Bruce W. Frier Associate Professor Achim Timmermann ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the support and encouragement of many people both within and outside of academia. I would first of all like to thank all those on my committee for reading drafts of my work and providing constructive feedback, especially Basil Dufallo and Ruth R. Caston, both of who read my chapters at early stages and pushed me to find what I wanted to say – and say it well. I also cannot thank enough all the graduate students in the Department of Classical Studies at the University of Michigan for their support and friendship over the years, without either of which I would have never made it this far. Marin Turk in Slavic Languages and Literature deserves my gratitude, as well, for reading over drafts of my chapters and providing insightful commentary from a non-classicist perspective. And I of course must thank the Department of Classical Studies and Rackham Graduate School for all the financial support that I have received over the years which gave me time and the peace of mind to develop my ideas and write the dissertation that follows. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………………………ii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS……………………………………………………………………iv ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………………....v CHAPTER I. -

Virgil, Aeneid 11 (Pallas & Camilla) 1–224, 498–521, 532–96, 648–89, 725–835 G

Virgil, Aeneid 11 (Pallas & Camilla) 1–224, 498–521, 532–96, 648–89, 725–835 G Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary ILDENHARD INGO GILDENHARD AND JOHN HENDERSON A dead boy (Pallas) and the death of a girl (Camilla) loom over the opening and the closing part of the eleventh book of the Aeneid. Following the savage slaughter in Aeneid 10, the AND book opens in a mournful mood as the warring parti es revisit yesterday’s killing fi elds to att end to their dead. One casualty in parti cular commands att enti on: Aeneas’ protégé H Pallas, killed and despoiled by Turnus in the previous book. His death plunges his father ENDERSON Evander and his surrogate father Aeneas into heart-rending despair – and helps set up the foundati onal act of sacrifi cial brutality that caps the poem, when Aeneas seeks to avenge Pallas by slaying Turnus in wrathful fury. Turnus’ departure from the living is prefi gured by that of his ally Camilla, a maiden schooled in the marti al arts, who sets the mold for warrior princesses such as Xena and Wonder Woman. In the fi nal third of Aeneid 11, she wreaks havoc not just on the batt lefi eld but on gender stereotypes and the conventi ons of the epic genre, before she too succumbs to a premature death. In the porti ons of the book selected for discussion here, Virgil off ers some of his most emoti ve (and disturbing) meditati ons on the tragic nature of human existence – but also knows how to lighten the mood with a bit of drag. -

THE MARS ULTOR COINS of C. 19-16 BC

UNIWERSYTET ZIELONOGÓRSKI IN GREMIUM 9/2015 Studia nad Historią, Kulturą i Polityką s . 7-30 Victoria Győri King’s College, London THE MARS ULTOR COINS OF C. 19-16 BC In 42 BC Augustus vowed to build a temple of Mars if he were victorious in aveng- ing the assassination of his adoptive father Julius Caesar1 . While ultio on Brutus and Cassius was a well-grounded theme in Roman society at large and was the principal slogan of Augustus and the Caesarians before and after the Battle of Philippi, the vow remained unfulfilled until 20 BC2 . In 20 BC, Augustus renewed his vow to Mars Ultor when Roman standards lost to the Parthians in 53, 40, and 36 BC were recovered by diplomatic negotiations . The temple of Mars Ultor then took on a new role; it hon- oured Rome’s ultio exacted from the Parthians . Parthia had been depicted as a prime foe ever since Crassus’ defeat at Carrhae in 53 BC . Before his death in 44 BC, Caesar planned a Parthian campaign3 . In 40 BC L . Decidius Saxa was defeated when Parthian forces invaded Roman Syria . In 36 BC Antony’s Parthian campaign was in the end unsuccessful4 . Indeed, the Forum Temple of Mars Ultor was not dedicated until 2 BC when Augustus received the title of Pater Patriae and when Gaius departed to the East to turn the diplomatic settlement of 20 BC into a military victory . Nevertheless, Augustus made his Parthian success of 20 BC the centre of a grand “propagandistic” programme, the principal theme of his new forum, and the reason for renewing his vow to build a temple to Mars Ultor . -

Augustanism in Ovid's Ars Amatoria

The Art of Making Oneself Hated: Rethinking (Anti-)Augustanism in Ovid’s Ars Amatoria The Art of Love: Bimillennial Essays on Ovid's Ars Amatoria and Remedia Amoris Steven Green Print publication date: 2007 Print ISBN-13: 9780199277773 Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: January 2010 DOI: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199277773.001.0001 The Art of Making Oneself Hated: Rethinking (Anti-)Augustanism in Ovid’s Ars Amatoria Sergio Casali DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199277773.003.0011 Abstract and Keywords This chapter focuses on the most overtly ‘Augustan’ part of the Ars – the Parthian expedition of Gaius Caesar (1.171-228) – and invites us to read the event as an episode that exposes tensions in the dynastic family, and draws attention to the spectacle and theatricality of the Emperor's Parthian campaign. Keywords: Ars Amatoria, Remedia Amoris, Augustus, politics, Rome, Parthia, Gaius Caesar My subtitle implies that I want to strike a balance, or to discuss the question of the Augustanism/anti-Augustanism of the Ars from a theoretical point of view. In fact, I won’t be doing that. The ‘Augustan’ side of the question has been treated in the best possible way by Mario Labate in his book L’arte di farsi amare,1 the ‘anti-Augustan’ side by Alison Sharrock, particularly in her article on ‘Ovid and the Politics of Reading’,2 and the ‘aporetic’ side by Duncan Kennedy and Alessandro Barchiesi.3 I couldn’t do it better. So, the first part of my title is more relevant for my chapter. It makes fairly clear, I think, my predilection for a good old anti-Augustan approach to Ovid. -

Imperial Authority and the Providence of Monotheism in Orosius's Historiae Adversus Paganos

Imperial Authority and the Providence of Monotheism in Orosius’s Historiae adversus paganos Victoria Leonard B.A. (Cardiff); M.A. (Cardiff) A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy School of History, Archaeology, and Religion Cardiff University August 2014 ii Declaration This work has not been submitted in substance for any other degree or award at this or any other university or place of learning, nor is being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signed ………………………………… (candidate) Date ……………………… STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD. Signed ………………………………… (candidate) Date ……………………… STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. The views expressed are my own. Signed ………………………………… (candidate) Date ……………………… STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ………………………………… (candidate) Date………………………… STATEMENT 4: PREVIOUSLY APPROVED BAR ON ACCESS I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loans after expiry of a bar on access previously approved by the Academic Standards & Quality Committee. Signed ………………………………… (candidate) Date………………………… iii Cover Illustration An image of an initial 'P' with a man, thought to be Orosius, holding a book. Acanthus leaves extend into the margins. On the same original manuscript page (f. 7) there is an image of a roundel enclosing arms in the lower margin. -

THE CONQUEST of ACRE De Expugnata Accone

1 THE CONQUEST OF ACRE De Expugnata Accone A Poetic Narrative of the Third Crusade Critical edition, translated with an introduction and notes by Tedd A. Wimperis Boston College Advanced Study Grant Summer 2009 2 Introduction In the year 1099 AD, the First Crusade, undertaken by European nobles and overseen by the Christian church, seized control of Jerusalem after a campaign of four years, setting up a Latin kingdom based in that city and establishing a Western presence in the Near East that would endure for two hundred years. After a series of clashes with Muslim armies, a second crusade was called that lasted from 1147-49. Then, in 1187, the delicate balance of powers erupted into conflict, and a unified Islamic force under the leadership of the legendary Saladin, Sultan of Egypt and Syria, swept through the Holy Land, cutting a swathe through the Crusader States until it brought Jerusalem itself to surrender. In the wake of this calamity, Europe fixed its intentions on reclaiming the land, and the Western powers again took up the Cross in what would be the Third Crusade. The crusade launched in 1189, and would thunder on until 1192, when the warring armies reached a stalemate and a treaty was signed between Saladin and King Richard I of England. But the very first engagement of the Third Crusade, and the longest-lasting, was the siege of Acre, a city on the coast of Palestine northwest of Jerusalem, important both militarily and as a center of trade. Acre was vigorously defended by the Muslim occupiers and fiercely fought for by the assembled might of the West for a grueling two years that saw thousands of casualties, famine, disease, and a brutal massacre. -

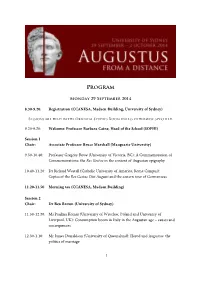

Augustus Program and Abstracts

Program Monday 29 September 2014 8.30-9.20: Registration (CCANESA, Madsen Building, University of Sydney) Sessions are held in the Oriental Studies Room unless otherwise specified. 9.20-9.50: Welcome: Professor Barbara Caine, Head of the School (SOPHI) Session 1 Chair: Associate Professor Bruce Marshall (Macquarie University) 9.50-10.40: Professor Gregory Rowe (University of Victoria, BC): A Commemoration of Commemorations: the Res Gestae in the context of Augustan epigraphy 10.40-11.20: Dr Richard Westall (Catholic University of America, Rome Campus): Copies of the Res Gestae Divi Augusti and the eastern tour of Germanicus 11.20-11.50 Morning tea (CCANESA, Madsen Building) Session 2 Chair: Dr Ben Brown (University of Sydney) 11.50-12.30: Ms Paulina Komar (University of Wrocław, Poland and University of Liverpool, UK): Consumption boom in Italy in the Augustan age – causes and consequences 12.30-1.10: Mr James Donaldson (University of Queensland): Herod and Augustus: the politics of marriage 1 1.10-2.30: Lunch (CCANESA, Madsen Building) Session 3 Chair: Dr Lea Beness (Macquarie University) 2.30-3.10: Dr Hannah Mitchell (University of Warwick): Monumentalising aristocratic achievement in triumviral Rome: Octavian’s competition with his peers 3.10-3.50: Dr Frederik Vervaet (University of Melbourne): Subsidia dominationi: the early careers of Tiberius and Drusus revisited 3.50-4.30: Mr Martin Stone (University of Sydney): Marcus Agrippa: Republican statesman or dynastic fodder? 4.30-5.00: Afternoon tea (CCANESA, Madsen Building) Session -

Illinois Classical Studies

immmmmu NOTICE: Return or renew alt Library Materials! The Minimum Fee for each Lost Book Is $50.00. The person charging this material is responsible for its return to the library from which it was withdrawn on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutilation, and underlining of books are reasons for discipli- nary action and may result In dismissal from the University. To renew call Telephone Center, 333-8400 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN m •' 2m MAR1 m ' 9. 2011 m nt ^AR 2 8 7002 H«ro 2002 - JUL 2 2ii^ APR . -.^ art Ll( S~tH ^ v^ a ILLINOIS CLASSICAL STUDIES VOLUME XIX 1994 ISSN 0363-1923 ILLINOIS CLASSICAL STUDIES VOLUME XIX 1994 SCHOLARS PRESS ISSN 0363-1923 ILLINOIS CLASSICAL STUDIES VOLUME XIX Studies in Honor of Mirosiav Marcovich Volume 2 The Board of Trustees University of Illinois Copies of the journal may be ordered from: Scholars Press Membership Services P.O. Box 15399 Aaanta,GA 30333-0399 Printed in the U.S.A. EDITOR David Sansone ADVISORY EDITORIAL COMMITTEE William M. Calder IH J. K. Newman Eric Hostetter S. Douglas Olson Howard Jacobson Maryline G. Parca CAMERA-READY COPY PRODUCED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF MARY ELLEN FRYER Illinois Classical Studies is published annually by Scholars Press. Camera- ready copy is edited and produced in the Department of the Classics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Each contributor receives fifty offprints free of charge. Contributions should be addressed to: The Editor, Illinois Classical Studies Department of the Classics 4072 Foreign Languages Building 707 South Mathews Avenue Urbana, Illinois 61801 Miroslav Marcovich Doctor of Humane Letters, Honoris Causa The University of Illinois 15 May 1994 . -

Time and History in Virgil's Aeneid by Rajesh Paul Mittal a Dissertation

Time and History in Virgil’s Aeneid by Rajesh Paul Mittal A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor David S. Potter, Chair Professor Victor Caston Professor Bruce W. Frier Assistant Professor Mira Seo To Jeb αὐτὰρ ὁ νόσφιν ἰδὼν ἀπομόρξατο δάκρυ ii Acknowledgments Producing this dissertation has been one of the most rewarding experiences of my life, and so it gives me tremendous pleasure to thank all of the people who contributed to its realization. First and foremost, thanks go to the members of my doctoral committee: David Potter, Victor Caston, Bruce Frier, and Mira Seo. I feel privileged to have had Professor Potter as my chair. In addition to being one of the finest Roman historians of his generation, he is a truly warm and understanding man, and I called upon that understanding at several points during this process. Professor Seo was truly a godsend, especially with regard to the literary aspects of my thesis. I am forever in her debt for the valuable contributions that she made on extremely short notice. Professor Caston was equally generous, and it pleases me to no end that a philosopher of his caliber has found nothing objectionable in my discussions of Plato, Stoicism, and Pythagoreanism. Finally, I must thank Professor Frier, not just for his work on my committee, but for all that he has meant to me in my time at the University of Michigan. Reading Livy with him for a prelim in 2007 will always be one of the fondest memories from my time in graduate school, in part because of Livy (whom I think we both properly appreciate), but even more so because Professor Frier is a true intellectual and marvelous person. -

Remarks on Ovid and the Golden Age of Augustus

SYMBOLAE PHILOLOGORUM POSNANIENSIUM GRAECAE ET LATINAE XXIX/2 • 2019 pp. 37–56. ISSN 0302–7384 DOI: 10.14746/sppgl.2020.XXIX.2.3 ADAM ŁUKASZEWICZ Uniwersytet Warszawski e-mail: [email protected] REMARKS ON OVID AND THE GOLDEN AGE OF AUGUSTUS ABSTRACT. Łukaszewicz, Adam, Remarks on Ovid and the Golden Age of Augustus (Uwagi o Owidiuszu i złotym wieku Augusta). Publius Ovidius Naso was an outstanding poet of the Augustan age who after a period of successful activity was suddenly sent to exile without a formal judicial procedure. Ovid wrote frivolous poems but inserted into his works also the obligatory praises of Augustus. The standard explanation of his relegation to Tomis is the licentious content of his Ars Amatoria, which were believed to offend the moral principles of Augustus. However, the Ars had been published several years before the exile. The poet himself in his Pontic writings mentions an unspecified error and a carmen, pointing also to the Ars, without, however, a clear explanation of the reason for his fall. The writer of the present contribution assumes that the actual reason for the relegation of the poet without a trial were the verses of his Metamorphoses and especially the passage about the wicked stepmothers preparing poison. That could offend Livia who, according to gossip, used poison to get rid of unwanted family members. Ovid was exiled, but the matter was too delicate for a public justification of the banishment. When writing ex Ponto the poet could not explicitly refer to the actual cause of his exile. Keywords: Ovid; Augustus; golden age; exile; Metamorphoses; lurida aconita. -

PASIPHAE and Daedalus and the FOUR Panels of the DOOR of Apollo's Temple

ISSN 0258–0802. LITERATŪRA 2010 52 (3) PASIPHAE AND DaedaLUS AND THE FOUR PANELS OF THE DOOR OF APOLLO’S TEMPLE (Vergil, Aeneid 6.20–30) Prof. Horatio Caesar Roger Vella Professor of the Department of Classics and Archeology, University of Malta Introduction and between the ecphrasis and the poem or its message4. It has been observed and widely agreed Some of these ecphrases, precisely upon that Vergil composed his Aeneid with because they tend to introduce something a structure, sometimes making symmetry important to come, are placed towards the even numerical1. It has also been shown that beginning of a book. We are here imme- to understand why Vergil wrote the poem, diately reminded of Odyssey VII, where one must depart from and be guided by Odysseus will meet Alcinous and Arete. Vergil’s own structure. Studies of Vergil’s Before Odysseus steps into the palace, structure of the Aeneid have indeed received Homer pauses for a numerically perfectly exhaustive scholarly attention2. Particular structured passage describing the garden, attention has also been given to appreciating and another numerically structured one the symbolism behind the Aeneid by means similarly describing the entrance to the of the observations made on the structure palace5. We understand what kind of people of the poem. the Phaeacians were, remote from the rest The relationship between narrative struc- of mankind, already from their horticultu- ture and symbolism is sometimes given ral and architectural activities, before we special focus by Vergil through ecphrasis3. meet them. Much has already been said about this met- hod of symbolically adverting the reader the openings of Aeneid I and VI of what will take place, and what has taken place; and of the connexion between the On two occasions, right at the beginning past and the present both in the ecphrasis of a book after a short introduction, Vergil presents us with such an ecphrasis.