Commentary on Valerius Maximus' Book IX.1-10. a Discourse on Vitia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elite Female Status Competition in Mid-Republican Rome and the Example of Tertia Aemilia

chapter 12 Mihi es aemula: Elite Female Status Competition in Mid-Republican Rome and the Example of Tertia Aemilia Lewis Webb Mihi es aemula.1 ∵ 1 Introduction Status competition was l’esprit du temps in mid-republican Rome (264– 133BCE), an impetus for elite male action, as prior studies have shown.2 If it was vital to elite men, did it also motivate elite women? (By elite, I mean the top tier of the two-tier equestrian aristocracy in mid-republican Rome.) Although Phyl- lis Culham and Emily Hemelrijk have found status competition among elite women, hitherto no study focuses on the phenomenon.3 So this chapter turns a lens on mid-republican Rome, investigating the rich evidence for what I term ‘elite female status competition’. Cicero alludes to such competition in his Pro Caelio.4 In a celebrated proso- popoeia Cicero summons Appius Claudius Caecus (RE 91, cos. 307, 296) ab inferis to condemn his descendant Clodia Ap.f. (RE 66), scion of the elite patri- 1 Plaut. Rud. 240. RE numbers are provided throughout, patronymics at the first occurrence of female names. On female nomenclature: Kajava 1994. For the magistracies: Broughton 1951; 1952. Latin text comes from the PHI Latin Corpus, Greek from the TLG. Translations are my own. Dates are BCE. 2 Harris 1979, 17–38; Hölkeskamp 1993; 2010, 99–100, 103–104, 122–123; 2011, 26; Rosenstein 1993, esp. 313; Flower 1996, 10–11, 72–73, 101, 107, 128–158, esp. 139; 2004, 327, 335, 338, 342; Mucci- grosso 2006, 186, 191, 194, 202; Steel 2006, 39, 45–46; Rüpke 2007, 144, 176, 218; Jehne 2011, 213, 215, 227; Zanda 2011, 13–14, 18, 25, 33, 36, 53–54, 57, 59, 65; Nebelin 2014; Beck 2016; Champion 2017, 15–16, 46–48; and Bernard in this volume. -

Valerius Maximus on Vice: a Commentary of Facta Et Dicta

Valerius Maximus on Vice: A Commentary on Facta et Dicta Memorabilia 9.1-11 Jeffrey Murray University of Cape Town Thesis Presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in the School of Languages and Literatures University of Cape Town June 2016 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Abstract The Facta et Dicta Memorabilia of Valerius Maximus, written during the formative stages of the Roman imperial system, survives as a near unique instance of an entire work composed in the genre of Latin exemplary literature. By providing the first detailed historical and historiographical commentary on Book 9 of this prose text – a section of the work dealing principally with vice and immorality – this thesis examines how an author employs material predominantly from the earlier, Republican, period in order to validate the value system which the Romans believed was the basis of their world domination and to justify the reign of the Julio-Claudian family. By detailed analysis of the sources of Valerius’ material, of the way he transforms it within his chosen genre, and of how he frames his exempla, this thesis illuminates the contribution of an often overlooked author to the historiography of the Roman Empire. -

The Salus Populi Romani Madonna in the World Author(S)

Sacred Art in an Age of Mechanical Reproduction: The Salus Title Populi Romani Madonna in the World Author(s) Mochizuki, Mia M. Citation Kyoto Studies in Art History (2016), 1: 129-144 Issue Date 2016-03 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/229454 © Graduate School of Letters, Kyoto University and the Right authors Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University 129 Sacred Art in an Age of Mechanical Reproduction: The Salus Populi Romani Madonna in the World Mia M. Mochizuki Baroque Machines A curious vignette provides an unlikely introduction to the world of elaborate Baroque machinery: a pudgy, if industrious putto raises the earth on high via a set of rotating gears that reduce the heavy lifting of a planet by leveraging a complicated Fac pedem figat et terram movebit besystem understood of integrated within pulleys its context (fig. 1).in theIts explanatoryImago primi motto, saeculi “ Societatis Iesu (Antwerp, ,” or “give him a place to fix his foot and he shall move the earth,” can only with its landmark accomplishments and obstacles. The emblem played on the word 1640), a book that commemorated the centennial anniversary of the Society of Jesus “conversion” as celebratingRegnorum both et Provinciarum the Society’s commitmentper Societatem to world-wideconversio.” explorationEmploying aand block the and“turning” tackle of pulley people system, to Christianity the scene on references such missions, Archimedes’ as the subtitle principles for this for harnessingchapter implies, the strength “ of compounded force to lift objects otherwise too heavy to home the point, the motto echoes Pappus of Alexandria’s record of the great inventor- move, the weight of the world paralleled to the difficulty of this endeavor. -

11Ffi ELOGIA of the AUGUSTAN FORUM

THEELOGIA OF THE AUGUSTAN FORUM 11ffi ELOGIA OF THE AUGUSTAN FORUM By BRAD JOHNSON, BA A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Brad Johnson, August 2001 MASTER OF ARTS (2001) McMaster University (Classics) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: The Elogia of the Augustan Forum AUTHOR: Brad Johnson, B.A. (McMaster University), B.A. Honours (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Dr. Claude Eilers NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 122 II ABSTRACT The Augustan Forum contained the statues offamous leaders from Rome's past. Beneath each statue an inscription was appended. Many of these inscriptions, known also as elogia, have survived. They record the name, magistracies held, and a brief account of the achievements of the individual. The reasons why these inscriptions were included in the Forum is the focus of this thesis. This thesis argues, through a detailed analysis of the elogia, that Augustus employed the inscriptions to propagate an image of himself as the most distinguished, and successful, leader in the history of Rome. III ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr. Claude Eilers, for not only suggesting this topic, but also for his patience, constructive criticism, sense of humour, and infinite knowledge of all things Roman. Many thanks to the members of my committee, Dr. Evan Haley and Dr. Peter Kingston, who made time in their busy schedules to be part of this process. To my parents, lowe a debt that is beyond payment. Their support, love, and encouragement throughout the years is beyond description. -

Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Bernard, Seth G., "Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C." (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 492. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Abstract MEN AT WORK: PUBLIC CONSTRUCTION, LABOR, AND SOCIETY AT MID-REPUBLICAN ROME, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard C. Brian Rose, Supervisor of Dissertation This dissertation investigates how Rome organized and paid for the considerable amount of labor that went into the physical transformation of the Middle Republican city. In particular, it considers the role played by the cost of public construction in the socioeconomic history of the period, here defined as 390 to 168 B.C. During the Middle Republic period, Rome expanded its dominion first over Italy and then over the Mediterranean. As it developed into the political and economic capital of its world, the city itself went through transformative change, recognizable in a great deal of new public infrastructure. -

The Roman Poets of the Augustan Age: Virgil by W

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Roman Poets of the Augustan Age: Virgil by W. Y. Sellar This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Roman Poets of the Augustan Age: Virgil Author: W. Y. Sellar Release Date: October 29, 2010 [Ebook 34163] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE ROMAN POETS OF THE AUGUSTAN AGE: VIRGIL*** THE ROMAN POETS OF THE AUGUSTAN AGE: VIRGIL. BY W. Y. SELLAR, M.A., LL.D. LATE PROFESSOR OF HUMANITY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH AND FELLOW OF ORIEL COLLEGE, OXFORD iv The Roman Poets of the Augustan Age: Virgil THIRD EDITION OXFORD AT THE CLARENDON PRESS OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS AMEN HOUSE, E.C. 4 London Edinburgh Glasgow New York Toronto Melbourne Capetown Bombay Calcutta Madras HUMPHREY MILFORD PUBLISHER TO THE UNIVERSITY vi The Roman Poets of the Augustan Age: Virgil IMPRESSION OF 1941 FIRST EDITION, 1877 THIRD EDITION, 1897 vii PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN TO E. L. LUSHINGTON, ESQ., D.C.L., LL.D., ETC. LATE PROFESSOR OF GREEK IN THE UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW. MY DEAR LUSHINGTON, Any old pupil of yours, in finishing a work either of classical scholarship or illustrative of ancient literature, must feel that he owes to you, probably more than to any one else, the impulse which directed him to these studies. -

Catullus, As Can’T Be Counted by Spies Nor an Evil Tongue Bewitch Us

&$78//867+(32(06 7UDQVODWHGE\$6.OLQH ã Copyright 2001 A. S. Kline, All Rights Reserved This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any NON-COMMERCIAL purpose. 2 &RQWHQWV 1. The Dedication: to Cornelius............................... 8 2. Tears for Lesbia’s Sparrow.................................. 9 2b. Atalanta.............................................................. 9 3. The Death of Lesbia’s Sparrow ......................... 10 4. His Boat ............................................................ 11 5. Let’s Live and Love: to Lesbia .......................... 13 6. Flavius’s Girl: to Flavius ................................... 14 7. How Many Kisses: to Lesbia ............................. 15 8. Advice: to himself.............................................. 16 9. Back from Spain: to Veranius............................ 17 10. Home Truths for Varus’s girl: to Varus........... 18 11. Words against Lesbia: to Furius and Aurelius . 19 12. Stop Stealing the Napkins! : to Asinius Marrucinus............................................................. 21 13. Invitation: to Fabullus...................................... 22 14. What a Book! : to Calvus the Poet................... 23 15. A Warning: to Aurelius.................................... 25 16. A Rebuke: to Aurelius and Furius.................... 26 17. The Town of Cologna Veneta.......................... 27 21. Greedy: To Aurelius. ....................................... 30 22. People Who Live in Glass Houses: to Varus ... 31 -

Due April 15

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Representation of Poverty in the Roman Empire Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3sp0w5c4 Author Larsen, Mik Robert Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Representation of Poverty in the Roman Empire A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Mik R Larsen 2015 © Copyright by Mik R Larsen 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Representation of Poverty in the Roman Empire by Mik R Larsen Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Ronald J. Mellor, Chair This dissertation investigates the cultural imagination of Roman elites regarding poverty in their society – how it was defined, how traditional and accepted images of poverty were deployed for rhetorical effect, and in what way elite attitudes toward poverty evolved over the course of the first century and a half under the Empire. It contends that the Roman conception of poverty was as a disordered discourse involving multiple competing definitions which frequently overlapped in practice. It argues that the inherent contradictions in Roman thought about poverty were rarely addressed or acknowledged by authors during this period. The Introduction summarizes scholarly approaches toward Roman perceptions of poverty and offers a set of definitions which describe the variant images of poverty in elite texts. The first chapter addresses poverty’s role in the histories of Livy, and the ways in which his presentation of poverty diverge from his assertion that the loss of paupertas was key to the decline of the Roman state. -

The Impact of the Roman Army (200 BC – AD 476)

Impact of Empire 6 IMEM-6-deBlois_CS2.indd i 5-4-2007 8:35:52 Impact of Empire Editorial Board of the series Impact of Empire (= Management Team of the Network Impact of Empire) Lukas de Blois, Angelos Chaniotis Ségolène Demougin, Olivier Hekster, Gerda de Kleijn Luuk de Ligt, Elio Lo Cascio, Michael Peachin John Rich, and Christian Witschel Executive Secretariat of the Series and the Network Lukas de Blois, Olivier Hekster Gerda de Kleijn and John Rich Radboud University of Nijmegen, Erasmusplein 1, P.O. Box 9103, 6500 HD Nijmegen, The Netherlands E-mail addresses: [email protected] and [email protected] Academic Board of the International Network Impact of Empire geza alföldy – stéphane benoist – anthony birley christer bruun – john drinkwater – werner eck – peter funke andrea giardina – johannes hahn – fik meijer – onno van nijf marie-thérèse raepsaet-charlier – john richardson bert van der spek – richard talbert – willem zwalve VOLUME 6 IMEM-6-deBlois_CS2.indd ii 5-4-2007 8:35:52 The Impact of the Roman Army (200 BC – AD 476) Economic, Social, Political, Religious and Cultural Aspects Proceedings of the Sixth Workshop of the International Network Impact of Empire (Roman Empire, 200 B.C. – A.D. 476) Capri, March 29 – April 2, 2005 Edited by Lukas de Blois & Elio Lo Cascio With the Aid of Olivier Hekster & Gerda de Kleijn LEIDEN • BOSTON 2007 This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NC 4.0 License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. -

Lays of Ancient Rome

Lays of Acient Rome Lays of Ancient Rome By Thomas Babbington Macaulay 1 Lays of Acient Rome Preface Horatius The Lay The Battle of the Lake Regillus The Lay Virginia The Lay The Prophecy of Capys The Lay That what i called the hitory of the Kings and early Consuls of Rome is to a great extent fabulus, few scholars have, since the ti of Beaufort, ventured to deny. It is certain that, more than three hundred and sixty years after the date ordinarily assigned for the foundatio of the city, the public records were, with scarcely an exception, destroyed by the Gauls. It is certain that the oldest annals of the coonwealth were compiled mre than a century and a half after th destruction of the records. It is certain, therefore, that the great Latin writers of the Augustan age did not possss those materials, without which a trustworthy account of the infancy of the republic could not possibly be framed. Those writers own, indeed, that the chronicles to which they had access were filled with battles that were never fought, and Consuls that were never inaugurated; and we have abundant proof that, in these chronicles, events of the greatest importance, suc as the issue of the war with Porsa and the issue of the war with Brennus, were grossly misrepresented. Under thes circumstances a wise man will look with great suspicio on the lged whi has com do to us. He will perhaps be inclined to regard th princes who are said to have founded the civil and religious institutions of Rom, the sons of Mars, and the husband of Egeria, as mere mythgial persage, of the same class with Persus and Ixion. -

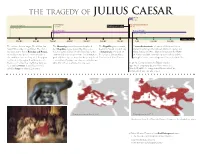

The Tragedy of Julius Caesar

THE TR AGEDY OF JULIUS CAESAR Transition 49–27 BC Coriolanus Caesar assassinated Roman Kingdom 494 BC Shakespeare’s play 44 BC 753–509 BC Roman Republic Roman Empire 509–49 BC 27 BC – 293 AD Roman Epochs 700 BC 600 BC 500 BC 400 BC 300 BC 200 BC 100 BC 1 AD 100 AD 200 AD The enforced vestal virgin, Rhea Silvia, has The Monarchy is overthrown and replaced The Republic grows corrupt, A second triumvirate is formed of Octavius Caesar twins fathered by the god Mars. The stolen by a Republic, a government by the people, begins to flounder and decay. (Julius Caesar’s great-nephew), Marcus Lepidus, and and abandoned twins, Romulus and Remus, headed by two consuls elected annually by the A triumvirate is formed of Mark Antony. In 27 BC, Mark Antony loses the Battle are fed by a woodpecker and nursed by a citizens and advised by a senate. A constitution Pompey the Great, Marcus of Actium and kills himself, Lepidus is exiled, and the she-wolf in a cave, the Lupercal. They grow gradually develops, centered on the principles of Crassus, and Julius Caesar. young Caesar becomes Augustus Caesar, Exalted One. up, found a city, argue, then Romulus kills a separation of powers and checks and balances. Remus and names the city Rome. OR it was All public offices are limited to one year. In 49 BC, Caesar crosses the Rubicon and is founded by Aeneas about this time. It is appointed temporary dictator three times; on ruled by kings for almost 250 years. -

The Emergence of Archival Records at Rome in the Fourth Century BCE

Foundations of History: The Emergence of Archival Records at Rome in the Fourth Century BCE by Zachary B. Hallock A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Greek and Roman History) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor David Potter, Chair Associate Professor Benjamin Fortson Assistant Professor Brendan Haug Professor Nicola Terrenato Zachary B. Hallock [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-0337-0181 © 2018 by Zachary B. Hallock To my parents for their endless love and support ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank Rackham Graduate School and the Departments of Classics and History for providing me with the resources and support that made my time as a graduate student comfortable and enjoyable. I would also like to express my gratitude to the professors of these departments who made themselves and their expertise abundantly available. Their mentoring and guidance proved invaluable and have shaped my approach to solving the problems of the past. I am an immensely better thinker and teacher through their efforts. I would also like to express my appreciation to my committee, whose diligence and attention made this project possible. I will be forever in their debt for the time they committed to reading and discussing my work. I would particularly like to thank my chair, David Potter, who has acted as a mentor and guide throughout my time at Michigan and has had the greatest role in making me the scholar that I am today. Finally, I would like to thank my wife, Andrea, who has been and will always be my greatest interlocutor.