Vernacular Theology, Home Birth and the Mormon Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moderating the Mormon Discourse on Modesty

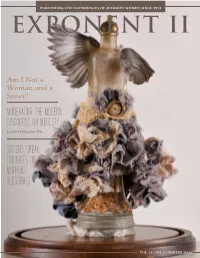

PUBLISHING THE EXPERIENCES OF MORMON WOMEN SINCE 1974 EXPONENT II Am I Not a Woman and a Sister? MODERATING THE MODERN DISCOURSE ON MODESTY Jennifer Finlayson-Fife SISTERS SPEAK: THOUGHTS ON MOTHERS’ BLESSINGS VOL. 33 | NO. 3 | WINTER 2014 04 PUBLISHING THE EXPERIENCES OF 18 Mormon Women SINCE 1974 14 16 WHAT IS EXPONENT II ? The purpose of Exponent II is to provide a forum for Mormon women to share their life 34 experiences in an atmosphere of trust and acceptance. This exchange allows us to better understand each other and shape the direction of our lives. Our common bond is our connection to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and our commitment to 24 women. We publish this paper as a living history in celebration of the strength and diversity 30 of women. 36 FEATURED STORIES ADDITIONAL FEATURES 03 LETTER FROM THE EDITOR 24 FLANNEL BOARD New Recruits in the Armies of Shelaman: Notes from a Primary Man MODERATING THE 04 AWAKENINGS Rob McFarland Making Peace with Mystery: To Prophet Jonah MORMON DISCOURSE ON MODESTY Mary B. Johnston 28 Reflections on a Wedding BY JENNIFER FINLAYSON-FIFE, WILMETTE, ILLINOIS Averyl Dietering 07 SISTERS SPEAK ON THE COVER: I believe the LDS cultural discourse around modesty is important because Sharing Experiences with Mothers’ Blessings 30 SABBATH PASTORALS Page Turner of its very real implications for women in the Church. How we construct Being Grateful for God’s Hand in a World I our sexuality deeply affects how we relate to ourselves and to one another. Moderating the Mormon Discourse on -

Exponent Ii History

ROUNDTABLE: EXPONENT II HISTORY EXPONENT II: EARLY DECISIONS Claudia L. Bushman Last year was the fortieth anniversary of Exponent II, a “modest, but sincere,” as we called it, little newspaper begun in Massachusetts written by and for LDS women. That brings it within two years of the lifetime that the old Woman’s Exponent was published from 1872 to 1914. All indicators suggest that Exponent II will last longer than the earlier paper. A student at Berkeley who was doing a thesis on Exponent II recently contacted me asking for some basic information about the paper. I said that she should try to look at early accounts, as later ones tend toward the extravagant. I told her that the paper was my husband’s idea, that we wrote the paper for ourselves and friends, and that we were not trying to reform Salt Lake. She said I was wrong, that it was inspired by Susan Whitaker Kohler’s discovery of the Woman’s Exponent, and that we had sent copies to the wives of General Authorities to enlist them. What is more, she cited my writings as evidence. She said if I didn’t know how things had happened, could I please direct her to someone who did. Well, history is malleable. I write history. Innocent little things in the past turn out to have big meaning. Exponent II is now old enough to have a mythic past. I add to it whenever I can. I don’t like to repeat myself, although I certainly do. Exponent II was part of big movements of its day, an LDS expression of the then current women’s liberation movement and also part of the Church’s New Mormon History. -

The Seriousness of Mormon Humor We Laugh Most Loudly at the Things We Feel Most Deeply

The Seriousness of Mormon Humor We laugh most loudly at the things we feel most deeply. By William A. Wilson ome time ago a friend of mine, talking to an historian, said he thought the historian and1 were working somewhat similar ground-to which the historian replied, "No, we do legitimate history, not folklore. Why, you should see some of the things Wilson studies. He even takes jokes seriously." I do indeed. And I hope to win others to this conviction. Perhaps even scholars with a little more vision than this particular historian have failed to S take either Mormon literary or folk humor seriously because they have believed that no such humor exists. As Richard Cracroft has pointed out, "one must search far into the first half of the twentieth century before turning up any intentionally sustained published humor" (SUNSTONE,May- 8 SUNSTONE June 1980, p. 31). Not until recent times, in novels like Samuel Taylor's Heaven Knows Why or in shorter pieces like Levi Peterson's "The Christianization of Coburn Heights" (in Canyons of Grace), do we find much written evidence that Mormons have been anything but the stolid, unsmiling souls the rest of the world has believed them to be. Nor is there in the folklore record-at least in the folklore record made available to us through the work of earlier scholars-much evidence to give a happier picture. The reason for this is simple. Just as earlier Mormon writers attempted to give literary expression to the clearly serious struggle to establish the kinedom of God in the western wasteland, so too did the first students of Mormon folklore seek oucthe folk expressions generated by that struggle. -

Summer 2016 Vol. 36 No. 1

SUMMER 2016 VOL. 36 NO. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE 06 20 11 COVER ART 05 LETTER FROM THE DECIDUOUS VENTRICLE 17 Natalie Stallings EDITOR 11 BOOK REVIEW MARGARET OLSEN MISSIONARY BARBIE FROM DIPLOMAT TO HEMMING Sydney Pritchett STRATEGIST: A REVIEW OF NAVIGATING MORMON FAITH CRISIS Eunice Yi McMurray 07 14 HEARTBREAK AND FOR ELSIE HOPE S.K. Julie Searcy 18 SISTERS SPEAK IDEAS FOR VISITING TEACHING WHAT IS EXPONENT II? Exponent II provides a forum for Mormon women to share their life experiences in an atmosphere of trust and acceptance. This exchange allows us to better understand each other and shape the direction of our lives. Our common bond is our connection to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter- day Saints and our commitment to women. We publish this paper as a living history in celebration of the strength and diversity of women. 27 24 36 23 FLANNEL BOARD 20 WOMEN IN THE LDS HOW (A TEENSY BIT CHURCH: A COURSE OF 31 30 OF) APOSTASY MADE ME A STUDY EXPONENT BETTER MORMON Kathryn Loosli Pritchett GENERATIONS Lauren Ard THE ROLES OF WOMEN 28 Lucy M. Hewlings WINDOWS AND WALLS Jan L. Tyler 26 Heather Moore-Farley 22 POETRY Rachel Rueckert POETRY MANDALA THE MIDDLE Mary Farnsworth Smith Stacy W. Dixon 34 HIDE AND SEEK 27 Brooke Parker BOOK REVIEW BAPTISM AND BOOMERANGS Lisa Hadley COVER ARTIST STATEMENT I am a freelance illustrator and artist living in Provo, Utah. When not drawing about ladies, and other lovely things, I like to use my personal work as a space to analyze domestic 21st century living. -

More Than Faith: Latter-Day Saint Women As Politically Aware and Active Americans, 1830-1860

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 2017 More Than Faith: Latter-Day Saint Women as Politically Aware and Active Americans, 1830-1860 Kim M. (Kim Michaelle) Davidson Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Davidson, Kim M. (Kim Michaelle), "More Than Faith: Latter-Day Saint Women as Politically Aware and Active Americans, 1830-1860" (2017). WWU Graduate School Collection. 558. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/558 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. More Than Faith: Latter-Day Saint Women as Politically Aware and Active Americans 1830-1860 By Kim Michaelle Davidson Accepted in Partial Completion of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Kathleen L. Kitto, Dean of the Graduate School ADVISORY COMMITTEE Chair, Dr. Jared Hardesty Dr. Hunter Price Dr. Holly Folk MASTER’S THESIS In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non- exclusive royalty-free right to archive, reproduce, distribute, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU. I represent and warrant this is my original work, and does not infringe or violate any rights of others. -

Policing the Borders of Identity At

POLICING THE BORDERS OF IDENTITY AT THE MORMON MIRACLE PAGEANT Kent R. Bean A dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2005 Jack Santino, Advisor Richard C. Gebhardt, Graduate Faculty Representative John Warren Nathan Richardson William A. Wilson ii ABSTRACT Jack Santino, Advisor While Mormons were once the “black sheep” of Christianity, engaging in communal economic arrangements, polygamy, and other practices, they have, since the turn of the twentieth century, modernized, Americanized, and “Christianized.” While many of their doctrines still cause mainstream Christians to deny them entrance into the Christian fold, Mormons’ performance of Christianity marks them as not only Christian, but as perhaps the best Christians. At the annual Mormon Miracle Pageant in Manti, Utah, held to celebrate the origins of the Mormon founding, Evangelical counter- Mormons gather to distribute literature and attempt to dissuade pageant-goers from their Mormonism. The hugeness of the pageant and the smallness of the town displace Christianity as de facto center and make Mormonism the central religion. Cast to the periphery, counter-Mormons must attempt to reassert the centrality of Christianity. Counter-Mormons and Mormons also wrangle over control of terms. These “turf wars” over issues of doctrine are much more about power than doctrinal “purity”: who gets to authoritatively speak for Mormonism. Meanwhile, as Mormonism moves Christianward, this creates room for Mormon fundamentalism, as small groups of dissidents lay claim to Joseph Smith’s “original” Mormonism. Manti is home of the True and Living Church of Jesus Christ of Saints of the Last Days, a group that broke away from the Mormon Church in 1994 and considers the mainstream church apostate, offering a challenge to its dominance in this time and place. -

The Marrow of Human Experience

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2006 The Marrow of Human Experience William A. Wilson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the Folklore Commons, and the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Wilson, W. A., Rudy, J. T., & Call, D. (2006). The marrow of human experience: Essays on folklore. Logan, UT: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Marrow of Human Experience ESSAYS ON FOLKLORE William A. Wilson Edited by Jill Terry Rudy The Marrow of Human Experience The Marrow of Human Experience ! Essays on Folklore By William A. Wilson Edited by Jill Terry Rudy with the assistance of Diane Call Utah State University Press Logan, UT Copyright © 2006 Utah State University Press All rights reserved Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322–7800 www.usu.edu/usupress/ Manufactured in the United States of America Printed on acid-free paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wilson, William Albert. The marrow of human experience : essays on folklore / by William A. Wilson ; edited by Jill Terry Rudy with the assistance of Diane Call. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN-13: 978-0-87421-653-0 (pbk.) ISBN- 0-87421-545-5 (e-book) ISBN-10: 0-87421-653-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Folklore and nationalism. 2. -

Mormon Studies Review Volume 1 Mormon Studies Review

Mormon Studies Review Volume 1 | Number 1 Article 27 1-1-2014 Mormon Studies Review Volume 1 Mormon Studies Review Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr2 Part of the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Review, Mormon Studies (2014) "Mormon Studies Review Volume 1," Mormon Studies Review: Vol. 1 : No. 1 , Article 27. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr2/vol1/iss1/27 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the All Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mormon Studies Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Review: <em>Mormon Studies Review</em> Volume 1 2014 MORMON Volume 1 Neal A. Maxwell Institute STUDIES for Religious Scholarship REVIEW Brigham Young University EDITOR J. Spencer Fluhman, Brigham Young University ASSOCIATE EDITORS D. Morgan Davis, Brigham Young University Benjamin E. Park, University of Cambridge EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Philip L. Barlow, Leonard J. Arrington Chair of Mormon History and Culture, Utah State University Richard L. Bushman, Gouverneur Morris Professor of History, Emeritus, Columbia University Douglas J. Davies, Professor in the Study of Religion, Durham University Eric A. Eliason, Professor of English, Brigham Young University James E. Faulconer, Richard L. Evans Professor of Religious Understanding and Professor of Philosophy, Brigham Young University Kathleen Flake, Richard L. Bushman Chair of Mormon Studies, University of Virginia Terryl L. Givens, James A. Bostwick Chair of English and Professor of Literature and Religion, University of Richmond Sarah Barringer Gordon, Arlin M. -

Mormon Movement to Montana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2004 Mormon movement to Montana Julie A. Wright The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Wright, Julie A., "Mormon movement to Montana" (2004). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5596. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5596 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of Montana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly- cited in published works and reports. **Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature** Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission Author's Signature: Date: Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. 8/98 MORMON MOVEMENT TO MONTANA by ' Julie A. Wright B.A. Brigham Young University 1999 presented in partial fulfillment o f the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The University o f Montana % November 2004 Approved by: Dean, Graduate School Date UMI Number: EP41060 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

The Paradox of Mormon Folklore

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 17 Issue 1 Article 5 1-1-1977 The Paradox of Mormon Folklore William A. Wilson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Wilson, William A. (1977) "The Paradox of Mormon Folklore," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 17 : Iss. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol17/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Wilson: The Paradox of Mormon Folklore the paradox of mormon folklore william A wilson As I1 began work on this paper I1 asked a number of friends what they would like to know about mormon folklore the re- sponses were at such cross purposes the task ahead seemed hope- less finally a colleague solved my problem by confessing that he knew next to nothing about the subject 1 I would like to know he said what mormon folklore is and what you fellows do with it tonight I1 should like to answer these questions I1 shall tell you what I1 at least consider mormon folklore to be I1 shall try to demonstrate what those of us who study it do with it and I1 shall try to persuade you that what we do is worth doing providing significant insight into our culture that we cannot always get in other ways in the 130 years since the word folklore was coined 1 folk loristsflorists have been trying -

LJA = Leonard J. Arrington Abel, Elijah, 1:290; Article On, 3:26

INDEX LJA = Leonard J. Arrington cotton, 1:7, 39, 858; early Utah expedi- tions in, 1:197–98; Future Farmers of America (FFA), 3:35, 135, 328n31, 385; A gender roles in 1:698–99, Israel Evans and, 1:715n32; Jensen Historical Farm, Abel, Elijah, 1:290; article on, 3:26; mis- 1:708–09; LJA and, 1:815–17, 821–24, sionary work, 3:220 829, 857–58, 2:202, 3:13, 15, 20, 31, abortion, 1:23, 458, 583, 786, 2:37n65, 131, 335, 389; LJA books on, 1:64–65; 3: 399, 436, 438, 637, 872, 902, 179, 316, potatoes, 1:15–16, 23; symposium on, 3: 456, 198. See also pregnancy 1:690. See also farming 2: Abravanel, Maurice, 130n109, 324, Ahanin, Marlena, 2:122, 340 438–39, 828 Albanese, Catherine L., 2:867, 3:107 Adam–God theory, 2:361, 585, 800, 860, Albrecht, Stan, 3:318, 441, 509 3:32–33, 37, 122, 224. See also funda- alcohol, abuse of, 1:320–21, 324–25, 393, mentalists 2:36, 120, 130, 147, 198, 399, 438n33, Adamson, Jack H., 1:481–82, 691, 478, 625, 691; 3:209, 584, 642; David 710, 832, 3:226; disillusionment of, Kennedy and, 1:729; dramatized in 1:301–02, 341–42; helps on Brigham theater, 1:539–40; Hearts Made Glad, Young books, 1:482n67, 568, 600, 1:252–53; Joseph Smith and, 1:757; 605–06, 756–57, 872; on the Bible, Prohibition, 2:276, 434–35, 437, 605; 1:389; unauthorized use of paper, 1:735, Word of Wisdom adherence, 1:757, 2:88–89, 470, 617 2:88, 95, 290, 310, 317, 320, 434n24, adoption, 1:354, 2:112, 139, 559, 654, 438, 517, 552, 637, 873; 3:193n42, 723n51, 756, 3:326–27; law of, 1:465; 412n35 services, 1:347n32, 354; wayward birth Alder, Douglas D., -

The Paradox of Mormon Folklore

The Paradox of Mormon Folklore William A. Wilson s I began work on this paper, I asked a number of friends what they Awould like to know about Mormon folklore. The responses were at such cross purposes the task ahead seemed hopeless. Finally, a colleague solved my problem by confessing that he knew next to nothing about the subject. “I would like to know,” he said, “what Mormon folklore is and what you fellows do with it.” Tonight I should like to answer these questions. I shall tell you what I, at least, consider Mormon folklore to be; I shall try to demonstrate what those of us who study it do with it; and I shall try to persuade you that what we do is worth doing, provid- ing significant insight into our culture that we cannot always get in other ways. In the 130 years since the word “folklore” was coined,1 folklorists have been trying unsuccessfully to decide what the word means. I shall not solve the problem here. Yet if we are to do business with each other, we must come to some common understanding of terms. Briefly, I con- sider folklore to be the unofficial part of our culture. When a Sunday School teacher reads to his class from an approved lesson manual, he is giving them what the Correlation Committee at least would call official religion; but when he illustrates the lesson with an account of the Three Nephites which he learned from his mother, he is giving them unof- ficial religion. Folklore, then, is that part of our culture that is passed through time and space by the process of oral transmission (by hearing 1.