DIALOGUE a Journal of Mormon Thought

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PHILIP L. BARLOW [email protected]

PHILIP L. BARLOW [email protected] EDUCATION Th.D. (1988) Harvard Divinity School, American Religious History & Culture M.T.S. (1980) Harvard, History of Christianity B.A. (1975) Weber State College, magna cum laude, History PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 2017: Inaugural Neal A. Maxwell Fellow, Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, Brigham Young University (calendar year) 2007—present: inaugural Leonard J. Arrington Professor of Mormon History & Culture, Dept. of History, Religious Studies Program, Utah State University 2011–2014: Director, Program in Religious Studies, Dept. of History, Utah State University 2001—2007: Professor of Christian History, Hanover College, Dept. of Theological Studies; (Associate Professor: 1994-2000; Dept. Chair: 1997-99; Assistant Professor: 1990-1994) 2006—2007: Associate Research Fellow, The Center for the Study of Religion & American Culture (at Indiana University/Purdue University at Indianapolis) 1988—90: Mellon Post-doctoral Fellow, University of Rochester, Dept. of Religion & Classics 1979–1985: Instructor, LDS Institute of Religion, Cambridge, MA SELECTED SERVICE/ACTIVITIES/HONORS (see also honors under: PUBLICATIONS/BOOKS) Periodic interviews in print and on camera in various media, including Associated Press, NBC News, CNN, CNN Online, CBS News, PBS/Frontline, National Public Radio, Utah Public Radio, the Boston Globe, New York Times, Chicago Tribune, USA Today, USA Today/College, Washington Post, Salt Lake Tribune, Deseret News, Mormon Times, and others, and news outlets and journals internationally in England, Germany, Israel, Portugal, France, and Al Jazeera/English. Board of Advisors, Executive Committee, Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, Brigham Young University (2017–present). Co-Director, Summer Seminar on Mormon Culture: ““Mormonism Engages the World: How the LDS Church Has Responded to Developments in Science, Culture, and Religion.” Brigham Young University, June–August 2017. -

Moderating the Mormon Discourse on Modesty

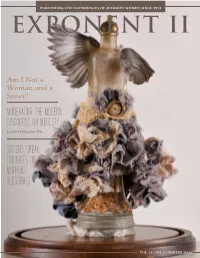

PUBLISHING THE EXPERIENCES OF MORMON WOMEN SINCE 1974 EXPONENT II Am I Not a Woman and a Sister? MODERATING THE MODERN DISCOURSE ON MODESTY Jennifer Finlayson-Fife SISTERS SPEAK: THOUGHTS ON MOTHERS’ BLESSINGS VOL. 33 | NO. 3 | WINTER 2014 04 PUBLISHING THE EXPERIENCES OF 18 Mormon Women SINCE 1974 14 16 WHAT IS EXPONENT II ? The purpose of Exponent II is to provide a forum for Mormon women to share their life 34 experiences in an atmosphere of trust and acceptance. This exchange allows us to better understand each other and shape the direction of our lives. Our common bond is our connection to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and our commitment to 24 women. We publish this paper as a living history in celebration of the strength and diversity 30 of women. 36 FEATURED STORIES ADDITIONAL FEATURES 03 LETTER FROM THE EDITOR 24 FLANNEL BOARD New Recruits in the Armies of Shelaman: Notes from a Primary Man MODERATING THE 04 AWAKENINGS Rob McFarland Making Peace with Mystery: To Prophet Jonah MORMON DISCOURSE ON MODESTY Mary B. Johnston 28 Reflections on a Wedding BY JENNIFER FINLAYSON-FIFE, WILMETTE, ILLINOIS Averyl Dietering 07 SISTERS SPEAK ON THE COVER: I believe the LDS cultural discourse around modesty is important because Sharing Experiences with Mothers’ Blessings 30 SABBATH PASTORALS Page Turner of its very real implications for women in the Church. How we construct Being Grateful for God’s Hand in a World I our sexuality deeply affects how we relate to ourselves and to one another. Moderating the Mormon Discourse on -

"Let a Hundred Flowers Blossom": Some Observations on Mormon Studies

Mormon Studies Review Volume 1 Number 1 Article 9 1-1-2014 "Let a Hundred Flowers Blossom": Some Observations on Mormon Studies Daniel C. Peterson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr2 Part of the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Peterson, Daniel C. (2014) ""Let a Hundred Flowers Blossom": Some Observations on Mormon Studies," Mormon Studies Review: Vol. 1 : No. 1 , Article 9. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr2/vol1/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mormon Studies Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Peterson: "Let a Hundred Flowers Blossom": Some Observations on Mormon Stud “Let a Hundred Flowers Blossom”: Some Observations on Mormon Studies Daniel C. Peterson THE VERY TERM MORMON STUDIES suggests its own broad definition as a “big tent.”1 I take the adjective Mormon to refer to the subject matter, and not to the practitioners. It doesn’t require that those involved in the study of Mormonism be Latter-day Saints or believers. Mormon studies simply involves studies of things Mormon, including the Mormon people and their history but also their scriptures and their doctrines. Nothing in the term privileges, say, research into the reception history of the scriptures over philological, archaeological, and historical approaches linked to their claimed origin or Sitz im Leben—even if, as in the case of the Book of Mormon, that origin is controversial.2 Nor, by the same token, does the term in any way discriminate against reception his- tory or attempts to explain the Book of Mormon as a product of the nine- teenth century. -

Mormon Studies Review Volume 4 Mormon Studies Review

Mormon Studies Review Volume 4 | Number 1 Article 25 1-1-2017 Mormon Studies Review Volume 4 Mormon Studies Review Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr2 Part of the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Review, Mormon Studies (2017) "Mormon Studies Review Volume 4," Mormon Studies Review: Vol. 4 : No. 1 , Article 25. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr2/vol4/iss1/25 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the All Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mormon Studies Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Review: <em>Mormon Studies Review</em> Volume 4 2017 MORMON Volume 4 STUDIES Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship REVIEW Brigham Young University Editor-in-chief J. Spencer Fluhman, Brigham Young University MANAGING EDITOR D. Morgan Davis, Brigham Young University ASSOCIATE EDITORS Melissa Wei-Tsing Inouye, University of Auckland Benjamin E. Park, Sam Houston State University EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Michael Austin, Executive Vice President for Academic Affairs, University of Evansville Philip L. Barlow, Leonard J. Arrington Chair of Mormon History and Culture, Utah State University Eric A. Eliason, Professor of English, Brigham Young University Kathleen Flake, Richard L. Bushman Chair of Mormon Studies, University of Virginia Terryl L. Givens, James A. Bostwick Chair of English and Professor of Literature and Religion, University of Richmond Matthew J. Grow, Director of Publications, Church History Department, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Grant Hardy, Professor of History and Religious Studies, University of North Carolina–Asheville David F. -

Exponent Ii History

ROUNDTABLE: EXPONENT II HISTORY EXPONENT II: EARLY DECISIONS Claudia L. Bushman Last year was the fortieth anniversary of Exponent II, a “modest, but sincere,” as we called it, little newspaper begun in Massachusetts written by and for LDS women. That brings it within two years of the lifetime that the old Woman’s Exponent was published from 1872 to 1914. All indicators suggest that Exponent II will last longer than the earlier paper. A student at Berkeley who was doing a thesis on Exponent II recently contacted me asking for some basic information about the paper. I said that she should try to look at early accounts, as later ones tend toward the extravagant. I told her that the paper was my husband’s idea, that we wrote the paper for ourselves and friends, and that we were not trying to reform Salt Lake. She said I was wrong, that it was inspired by Susan Whitaker Kohler’s discovery of the Woman’s Exponent, and that we had sent copies to the wives of General Authorities to enlist them. What is more, she cited my writings as evidence. She said if I didn’t know how things had happened, could I please direct her to someone who did. Well, history is malleable. I write history. Innocent little things in the past turn out to have big meaning. Exponent II is now old enough to have a mythic past. I add to it whenever I can. I don’t like to repeat myself, although I certainly do. Exponent II was part of big movements of its day, an LDS expression of the then current women’s liberation movement and also part of the Church’s New Mormon History. -

B. a Chronological List of English Reader-Friendly Sources on Hebrew-Like Literary Language and Structures That Relate to the Book of Mormon

B. A Chronological List of English Reader-Friendly Sources on Hebrew-like Literary Language and Structures That Relate to the Book of Mormon In the chronological listing of articles and books, the following system of identification will be used: Year = after 1830, non-LDS scholarly Year = after 1830, LDS Year^ = anti-Mormon 1829-30 Original Manuscript of the Book of Mormon As Joseph dictated, Oliver Cowdery and other scribes wrote the dictation on folded foolscap paper (6 5/8 x 16 ½), line-after-line without significant punctuation, capitalization or paragraphs. Roughly 25 per cent of the Original Manuscript survives. Original Manuscript lightplanet.com 205 (Sources: 1830→ Present) (Sources Shirley R. Heater, “History of the Manuscripts of the Book of Mormon.” In Recent Book of Mormon Developments, vol. 2, 1992: 80-88) 1830 Printer’s Manuscript of the Book of Mormon In preparation for printing, Joseph had Oliver copy the Original Manuscript into what is called the “Printer’s Manuscript.” According to Royal Skousen, the Printers Manuscript is not an exact copy of the Original Manuscript. Skousen found on the average three changes per Original Manuscript page. In Skousen’s view, “these changes appear to be natural scribal errors; there is little or no evidence of conscious editing. Most of the changes were minor, and about one in five produced a discernible difference in meaning.” The Printers Manuscript has wholly survived except for two lines. (Source: Royal Skousen, “Manuscripts of the Book of Mormon.” In To All the World: The Book of Mormon Articles from the Encyclopedia of Mormonism, p. 179) Printers Manuscript stepbystep 1830 1830 Edition of The Book of Mormon (Palmyra) Working for owner E.B. -

Full Journal

Editor in Chief Steven C. Harper Associate Editor Susan Elizabeth Howe Involving Readers Editorial Board in the Latter-day Saint Trevor Alvord media Academic Experience Richard E. Bennett Church history Carter Charles history W. Justin Dyer social science Dirk A. Elzinga linguistics Sherilyn Farnes history James E. Faulconer philosophy/theology Kathleen Flake religious studies Ignacio M. Garcia history Daryl R. Hague translation Taylor Halvorson, scripture and innovation David F. Holland religious history Kent P. Jackson scripture Megan Sanborn Jones theater and media arts Ann Laemmlen Lewis independent scholar Kerry Muhlestein Egyptology Armand L. Mauss sociology Marjorie Newton history Josh E. Probert material culture Susan Sessions Rugh history Herman du Toit visual arts Lisa Olsen Tait history Greg Trimble, entrepreneurship, internet engineering John G. Turner history Gerrit van Dyk Church history John W. Welch law and scripture Frederick G. Williams cultural history Jed L. Woodworth history STUDIES QUARTERLY BYU Vol. 58 • No. 3 • 2019 ARTICLES 4 The History of the Name of the Savior’s Church: A Collaborative and Revelatory Process K. Shane Goodwin 42 Voice from the Dust A Shoshone Perspective on the Bear River Massacre Darren Parry 58 The Nauvoo Music and Concert Hall: A Prelude to the Exodus Darrell Babidge 105 Naturalistic Explanations of the Origin of the Book of Mormon: A Longitudinal Study Brian C. Hales 149 The Office of Church Recorder: A Conversation with Elder Steven E. Snow Keith A. Erekson COVER ART 78 She Will Find What Is Lost: Brian Kershisnik’s Artistic Response to the Problem of Human Suffering Cris Baird ESSAY 99 Burning the Couch: Some Stories of Grace Robbie Taggart POETRY 98 First Argument Darlene Young BOOK REVIEW 186 Sex and Death on the Western Emigrant Trail: The Biology of Three American Tragedies by Donald K. -

Vernacular Theology, Home Birth and the Mormon Tradition

Vernacular Theology, Home Birth and the Mormon Tradition by © Christine Blythe A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Folklore Memorial University of Newfoundland April 2018 St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador Abstract This thesis examines the personal experience narratives of Mormon birth workers and mothers who home birth. I argue that embedded in their stories are vernacular beliefs that inform their interpretations of womanhood and broaden their conceptions of Mormon theology. Here I trace the tradition of Mormon midwifery from nineteenth century Mormonism into the present day and explore how some Mormon birth workers’ interpretation of the Mormon past became a means of identity formation and empowerment. I also examine how several recurring motifs reveal how the pain of natural childbirth—either in submission to or in the surmounting of— became a conduit of theological innovations for the women participating in this research. Their stories shed light on and respond to institutional positions on the family and theological ambiguities about woman’s role in the afterlife. Drawing on the language of my contributors, I argue that in birth women are sacralized, opening the door to an expanding (and empowering) image of Mormon womanhood. Blythe, ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It has been my privilege to work with so many inspiring and intelligent women whose stories make up the better part of my research. My deepest appreciation goes out to each of my contributors for their willingness to participate in this project. I am also indebted to the faculty in the Department of Folklore at Memorial University of Newfoundland for their encouragement and instruction throughout the course of my Master’s Degree, In particular, I thank Maria Lesiv who offered advice on an earlier and abbreviated draft of my thesis and Holly Everett for her abiding encouragement. -

Summer 2016 Vol. 36 No. 1

SUMMER 2016 VOL. 36 NO. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE 06 20 11 COVER ART 05 LETTER FROM THE DECIDUOUS VENTRICLE 17 Natalie Stallings EDITOR 11 BOOK REVIEW MARGARET OLSEN MISSIONARY BARBIE FROM DIPLOMAT TO HEMMING Sydney Pritchett STRATEGIST: A REVIEW OF NAVIGATING MORMON FAITH CRISIS Eunice Yi McMurray 07 14 HEARTBREAK AND FOR ELSIE HOPE S.K. Julie Searcy 18 SISTERS SPEAK IDEAS FOR VISITING TEACHING WHAT IS EXPONENT II? Exponent II provides a forum for Mormon women to share their life experiences in an atmosphere of trust and acceptance. This exchange allows us to better understand each other and shape the direction of our lives. Our common bond is our connection to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter- day Saints and our commitment to women. We publish this paper as a living history in celebration of the strength and diversity of women. 27 24 36 23 FLANNEL BOARD 20 WOMEN IN THE LDS HOW (A TEENSY BIT CHURCH: A COURSE OF 31 30 OF) APOSTASY MADE ME A STUDY EXPONENT BETTER MORMON Kathryn Loosli Pritchett GENERATIONS Lauren Ard THE ROLES OF WOMEN 28 Lucy M. Hewlings WINDOWS AND WALLS Jan L. Tyler 26 Heather Moore-Farley 22 POETRY Rachel Rueckert POETRY MANDALA THE MIDDLE Mary Farnsworth Smith Stacy W. Dixon 34 HIDE AND SEEK 27 Brooke Parker BOOK REVIEW BAPTISM AND BOOMERANGS Lisa Hadley COVER ARTIST STATEMENT I am a freelance illustrator and artist living in Provo, Utah. When not drawing about ladies, and other lovely things, I like to use my personal work as a space to analyze domestic 21st century living. -

Learning to Read the Book of Mormon with Mature Historical Understanding

“Put Away Childish Things” Learning to Read the Book of Mormon with Mature Historical Understanding Neal Rappleye 2017 FairMormon Conference A Tale of Two Jerusalems, Part 1: The Amarna Letters, 14th century BC In 1887, a cache of cuneiform tablets dated to the mid-14th century BC was discovered in Amarna, Egypt. The collection primarily consisted of letters written by Canaanite rulers petitioning the Pharaoh to aide them in their petty squabbles with neighboring cities, including six letters written by the King of Jerusalem.1 Based on these letters, Jerusalem at the time was a powerful regional capital, ruling over a “land” or even multiple “lands,” controlling subsidiary towns, and was even powerful An archive of 14th c. BC letters found in Amarna, Egypt, includes six letters from the King of Jerusalem, despite there being no archaeological evidence for Jerusalem at that time. enough to seize possession of the towns Map by Jasmin Gimenez. belonging to rival cities.2 There is just one problem: there is no archaeological evidence for this Jerusalem. According to Margreet Steiner, “No trace has ever been found of any city that could have been the [Jerusalem] of the 1 For background on the El Amarna letters, see Richard S. Hess, “Amarna Letters,” in Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible, ed. David Noel Freedman (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2000), 50–51; Lester L. Grabbe, Ancient Israel: What Do We Know and How Do We Know It?, rev. ed. (New York, NY: Bloomsbury/T&T Clark), 44–47. The letters from the king of Jerusalem are EA 285–290. -

The Dilemma of the Mormon Rationalist

The Dilemma of the Mormon Rationalist Robert D. Anderson Of all hatreds there is none greater than ignorance against knowledge. —Galileo [The trial of Galileo] was a vast conflict of world views of whose implications the principals themselves could not be fully aware. —Georgio de Santillana1 IN THE DECLINE OF CHRISTIANITY OVER THE PAST 900 YEARS, no incident has so symbolized the struggle between faith and rationality as has the trial of Galileo Galilei (1564-1642). With his development of the telescope and discovery of the moonlike phases of Venus, he concluded that the sun was the center of the universe and challenged a literal interpretation of the Bible. The Catholic church enjoined him to present his views as a hy- pothesis only and to give equal weight to the traditional view of the uni- verse. When he published a book in 1632 that presented his sun-centered view, he was called to Rome, threatened with torture, and judged by the Inquisition. Strictly speaking, the church never formally declared the the- ory of a sun-centered universe heretical, and "Galileo was tried not so much for heresy as for disobeying orders." Found guilty of the Vehement Suspicion of Heresy, he avoided torture and death by recanting and was condemned to imprisonment in his own house in 1633; he died nine years later.2 During that time, however, he continued to believe in a sun- 1. Georgio de Santillana, The Crime of Galileo (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1955), both quotes on 137. 2. While Galileo stood condemned by the highest councils in the church, Catholics em- phasized that neither the Copernican view nor Galileo was condemned by the pope ex cathe- dra. -

Max Perry Mueller CV 2020

MAX PERRY MUELLER University of Nebraska-Lincoln/Department of Classics and Religious Studies 337-254-7552 • [email protected] EDUCATION Harvard University, Cambridge, MA Ph.D., June, 2015, The Committee on the Study of Religion (American religious history). Dissertation: “Black, White, and Red: Race and the Making of the Mormon People, 1830- 1880.” Committee: David Hempton (co-chair), Laurel Thatcher Ulrich (co-chair), Marla Frederick, David Holland. Comprehensive Exams specializations (with distinction): Native American Religious History and African-American Religious History Secondary Doctoral Field, 2013, African and African American Studies. Harvard Divinity School, Cambridge, MA M.T.S., 2008, Harvard Divinity School. Carleton College, Northfield, MN B.A., 2003, magna cum laude. Double major in Religion (Distinction in major) and French and Francophone Studies (Distinction in major). PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS 2016-Present The University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Department of Classics and Religious Studies, Assistant Professor. Fellow in the Center for Great Plains Studies Affiliated with the Institute for Ethnic Studies (applied) 2015-2016 Amherst College, Religion Department, Visiting Assistant Professor. 2014-2015 Mount Holyoke College, Religion Department, Visiting Lecturer. Fall 2013 Carleton College, Religion Department, Visiting Lecturer. 2010-2013 Harvard University, Teaching Fellow and Tutor. 2003-2006 Episcopal School of Acadiana (Lafayette, LA), Upper School French Teacher and Head Cross-Country and Track Coach (boys and girls). 1 PUBLICATIONS Book Projects Race and the Making of the Mormon People, 1830-1908. The University of North Carolina Press, 2017. * Winner of John Whitmore Historical Association, Best Documentary Book (2018) Reviewed in: The Atlantic, Harvard Divinity School Bulletin, Choice, Reading Religion, Church History, Nova Religio, BYU Studies Quarterly, The Journal of Mormon History, Mormon Studies Review, Western History Quarterly, American Historical Review, Utah Historical Quarterly, among others.