The Paradox of Mormon Folklore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hey La Hey (2009)

Hey La Hey (2009) So Am I Lately you've been actin' awfully angry Now I hear that you're headed back to You said it feels like your life's passin' Austin you by Now I don't even need to ask why I'm not asking you to save me You can reach me at my sister's house in You say you're hurtin' baby so am I Boston You say you're runnin' baby so am I 1. So Am I 2. Hard To Break The walls we need to climb seem Darlin' will you keep a candle burning 3. I Wanna Know Why rather daunting cuz this love I refuse to let it die 4. The Great American Novel The fields we need to cross stretch on I can feel you sweet soul softly yearning 5. Room 411 for miles The words you spoke last night were You say you're lonely baby so am I 6. The Year It All so haunting You say you're runnin' baby so am I Went Wrong You say you're frightened well baby If you say you'll hold on baby so will I 7. Hey La Hey So am I 8. Dream Com True 9. The Ballad Of But you never wanna listen Johnny Diversey It seems like you wanna go it alone 10. Carry Your Cross I don't know what you're missin', and 11. So Am I (Bonus Track) I hate to admit But it feels we're sinkin' like a stone All alone I've been fighting this battle It seems to me that you don't wanna try I can hear your death drum begin to rattle You say you're tired baby so am I I'll scream your name until you finally hear me I'll scream your name 'neath the sheltering sky I wish in this moment your were near me You say you're lonely baby so am I And I'm hollowed and I'm haggard And I'm in desperate need of a shower Into these -

University Microfilms International 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 USA St

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand marking: or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

MDM Book Layout 12.14.18.Indd

CHRISTIANS MIGHT BE CRAZY ANSWERING THE TOP 7 OBJECTIONS TO CHRISTIANITY Mark Driscoll Christians Might Be Crazy © 2018 by Mark Driscoll ISBN: Unless otherwise indicated, scripture quotations are from The Holy Bible, English Standard Version, copyright 2001 by Crossway Bibles a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All right reserved. All emphases in Scripture quotations have added by the author. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, Mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher, except as provided for by USA copyright law. CONTENTS PREFACE: A PROJECT FOR SUCH A TIME AS THIS . 1 OBJECTION #1: INTOLERANCE . 25 “Jesus Freaks are intolerant bigots.” OBJECTION #2: ABORTION & GAY MARRIAGE . 47 “I have different views on social issues like abortion or gay marriage.” OBJECTION #3: POLITICS . 65 “I don’t like how some Christian groups meddle in politics.” OBJECTION #4: HYPOCRISY . 83 “Most Christians are hypocrites.” OBJECTION #5: EXCLUSIVITY . 101 “There are lots of religions, and I’m not sure only ONE has to be the right way.” OBJECTION #6: INEQUALITY. 119 “All people are not created equal in the Christian faith.” OBJECTION #7: SCRIPTURE . 135 “I don’t share the same beliefs that the Christian faith tells me I should.” CONCLUSION: REDEMPTION FROM RELIGION AND REBELLION . 155 NOTES . 173 PREFACE A PROJECT FOR SUCH A TIME AS THIS was hoping to release the findings of the massive project this book is based I upon some years ago, but a complicated season kept that from happening. -

The Seriousness of Mormon Humor We Laugh Most Loudly at the Things We Feel Most Deeply

The Seriousness of Mormon Humor We laugh most loudly at the things we feel most deeply. By William A. Wilson ome time ago a friend of mine, talking to an historian, said he thought the historian and1 were working somewhat similar ground-to which the historian replied, "No, we do legitimate history, not folklore. Why, you should see some of the things Wilson studies. He even takes jokes seriously." I do indeed. And I hope to win others to this conviction. Perhaps even scholars with a little more vision than this particular historian have failed to S take either Mormon literary or folk humor seriously because they have believed that no such humor exists. As Richard Cracroft has pointed out, "one must search far into the first half of the twentieth century before turning up any intentionally sustained published humor" (SUNSTONE,May- 8 SUNSTONE June 1980, p. 31). Not until recent times, in novels like Samuel Taylor's Heaven Knows Why or in shorter pieces like Levi Peterson's "The Christianization of Coburn Heights" (in Canyons of Grace), do we find much written evidence that Mormons have been anything but the stolid, unsmiling souls the rest of the world has believed them to be. Nor is there in the folklore record-at least in the folklore record made available to us through the work of earlier scholars-much evidence to give a happier picture. The reason for this is simple. Just as earlier Mormon writers attempted to give literary expression to the clearly serious struggle to establish the kinedom of God in the western wasteland, so too did the first students of Mormon folklore seek oucthe folk expressions generated by that struggle. -

CRATERS of the MOON a Thesis Submitted to Kent State University

CRATERS OF THE MOON A thesis submitted To Kent State University in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts by Jack Shelton Boyle May, 2016 © Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published materials Thesis written by Jack Shelton Boyle B.A., The College of Wooster, 2008 M.F.A., Kent State University, 2016 Approved by Chris Barzak________________________, Advisor Dr. Robert Trogdon, Ph.D._____________, Chair, Department of English Dr. James Blank, Ph.D._______________, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences iii TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................................................. iii POLAROIDS ................................................................................................................... 1 HANDS SHAPED LIKE GUNS ...................................................................................... 18 SUNFLOWER ............................................................................................................... 22 QUITTING ..................................................................................................................... 24 THE DISAPPEARING MAN .......................................................................................... 41 CHICKENS .................................................................................................................... 42 UNITY ........................................................................................................................... 48 MOON -

Vernacular Theology, Home Birth and the Mormon Tradition

Vernacular Theology, Home Birth and the Mormon Tradition by © Christine Blythe A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Folklore Memorial University of Newfoundland April 2018 St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador Abstract This thesis examines the personal experience narratives of Mormon birth workers and mothers who home birth. I argue that embedded in their stories are vernacular beliefs that inform their interpretations of womanhood and broaden their conceptions of Mormon theology. Here I trace the tradition of Mormon midwifery from nineteenth century Mormonism into the present day and explore how some Mormon birth workers’ interpretation of the Mormon past became a means of identity formation and empowerment. I also examine how several recurring motifs reveal how the pain of natural childbirth—either in submission to or in the surmounting of— became a conduit of theological innovations for the women participating in this research. Their stories shed light on and respond to institutional positions on the family and theological ambiguities about woman’s role in the afterlife. Drawing on the language of my contributors, I argue that in birth women are sacralized, opening the door to an expanding (and empowering) image of Mormon womanhood. Blythe, ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It has been my privilege to work with so many inspiring and intelligent women whose stories make up the better part of my research. My deepest appreciation goes out to each of my contributors for their willingness to participate in this project. I am also indebted to the faculty in the Department of Folklore at Memorial University of Newfoundland for their encouragement and instruction throughout the course of my Master’s Degree, In particular, I thank Maria Lesiv who offered advice on an earlier and abbreviated draft of my thesis and Holly Everett for her abiding encouragement. -

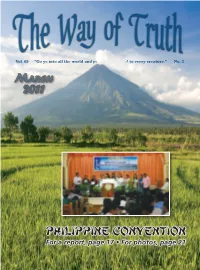

Philippine Convention for a Report, Page 17 • for Photos, Page 21

Vol. 69 “Go ye into all the world and preach the gospel to every creature.” No. 3 MARCH 2011 Philippine Convention For a report, page 17 • For photos, page 21 cover.indd 1 2/1/2011 3:23:22 PM Editorial not dancing as we think of dancing! Why do I say that? Because the priests were walking along, carrying the RELIGIOUS DEMONSTRATIONS ark and moving. They were not standing still. There were various times when the people shouted E READ in I Corinthians 12:4-7, “Now there are and praised the Lord. After the Ark was returned by diversities of gifts, but the same Spirit. And there the Philistines, David decided to bring it to Jerusalem. W are differences of administrations, but the same As they did, the people played their instruments and Lord. And there are diversities of operations, but it is shouted (I Chronicles 13:7, 8). However, when Uzza the same God which worketh all in all. But the mani- tried to steady the Ark and touched it, God smote him— festation of the Spirit is given to every man to profit Verses 9 and 10. So it was not brought into the city at withal.” that time. Later, as stated above, they did bring it into In this passage of scripture, we are told that the the city. When the foundation of the second temple was gifts, administrations, and operations of the Holy Spirit laid, the people sang, shouted, and praised the Lord— are not given for the profit of any one person, but are Ezra 3:11-13. -

10 TRUTHS YOU CAN KNOW ABOUT HEAVEN Page 18

Think February 2013-Covers_Covers 1/17/13 2:16 PM Page 1 FEBRUARY 2013 10 TRUTHS YOU CAN KNOW ABOUT HEAVEN Page 18 CURRENT ISSUES FROM A DISTINCTLY CHRISTIAN VIEW IS HEAVEN REAL? $3.95 Think February 2013-Covers_Covers 1/17/13 2:16 PM Page 2 “It is sown a natural body, it is raised a spiritual body. There is a natural body, and there is a spiritual body.” Think February 2013-Interior_Interior 1/17/13 2:03 PM Page 3 DAILY WALK 12 FEBRUARY 2013 F eatures _______10 The Apologetics of Desire: How Humanity’s Universal Longing For God Suggests His Existence JOE PUCKETT, JR. _______12 Eli’s Story KRISTIE WILLIAMS _______16 Into the Light TREVOR MAJOR _______18 10 Truths You Can Know About Heaven WESLEY WALKER 20 _______20 What the Old Testament Says About the Afterlife DEWAYNE BRYANT _______22 Grief and Hope ASHLEY SMITH 22 I n this issue 14 Proof of Heaven 27 The Rest of the Story: Connections D epartments 4 FROM THE EDITORS 6 MAILBAG 7 SOLID GROUND 8 HEART OF THE MATTER 9 FAMILIES OF FAITH 24 SMART FAITH 26 DISSECTING DELUSIONS 28 DIGGING DEEPER 29 A WOMAN’S PERSPECTIVE 31 FAITH MATTERS THINK | FEBRUARY 2013 3 Think February 2013-Interior_Interior 1/17/13 2:03 PM Page 4 EDITORS’ NOTE Brad Harrub, Keith Parker, Steve Higginbotham, Jay Lockhart, Willie Franklin, Jack Wilkie, and Steve Akin WHAT DO WE KNOW ABOUT HEAVEN? People desperately want to believe in an afterlife. Even many atheists legedly been instructed to come back to earth and tell others about what struggle with the notion that this life is all there is. -

Freestyle Rap Practices in Experimental Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 3-2-2017 On My Grind: Freestyle Rap Practices in Experimental Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy Evan Nave Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, Creative Writing Commons, Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Educational Methods Commons Recommended Citation Nave, Evan, "On My Grind: Freestyle Rap Practices in Experimental Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 697. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/697 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ON MY GRIND: FREESTYLE RAP PRACTICES IN EXPERIMENTAL CREATIVE WRITING AND COMPOSITION PEDAGOGY Evan Nave 312 Pages My work is always necessarily two-headed. Double-voiced. Call-and-response at once. Paranoid self-talk as dichotomous monologue to move the crowd. Part of this has to do with the deep cuts and scratches in my mind. Recorded and remixed across DNA double helixes. Structurally split. Generationally divided. A style and family history built on breaking down. Evidence of how ill I am. And then there’s the matter of skin. The material concerns of cultural cross-fertilization. Itching to plant seeds where the grass is always greener. Color collaborations and appropriations. Writing white/out with black art ink. Distinctions dangerously hidden behind backbeats or shamelessly displayed front and center for familiar-feeling consumption. -

More Than Faith: Latter-Day Saint Women As Politically Aware and Active Americans, 1830-1860

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 2017 More Than Faith: Latter-Day Saint Women as Politically Aware and Active Americans, 1830-1860 Kim M. (Kim Michaelle) Davidson Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Davidson, Kim M. (Kim Michaelle), "More Than Faith: Latter-Day Saint Women as Politically Aware and Active Americans, 1830-1860" (2017). WWU Graduate School Collection. 558. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/558 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. More Than Faith: Latter-Day Saint Women as Politically Aware and Active Americans 1830-1860 By Kim Michaelle Davidson Accepted in Partial Completion of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Kathleen L. Kitto, Dean of the Graduate School ADVISORY COMMITTEE Chair, Dr. Jared Hardesty Dr. Hunter Price Dr. Holly Folk MASTER’S THESIS In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non- exclusive royalty-free right to archive, reproduce, distribute, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU. I represent and warrant this is my original work, and does not infringe or violate any rights of others. -

Policing the Borders of Identity At

POLICING THE BORDERS OF IDENTITY AT THE MORMON MIRACLE PAGEANT Kent R. Bean A dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2005 Jack Santino, Advisor Richard C. Gebhardt, Graduate Faculty Representative John Warren Nathan Richardson William A. Wilson ii ABSTRACT Jack Santino, Advisor While Mormons were once the “black sheep” of Christianity, engaging in communal economic arrangements, polygamy, and other practices, they have, since the turn of the twentieth century, modernized, Americanized, and “Christianized.” While many of their doctrines still cause mainstream Christians to deny them entrance into the Christian fold, Mormons’ performance of Christianity marks them as not only Christian, but as perhaps the best Christians. At the annual Mormon Miracle Pageant in Manti, Utah, held to celebrate the origins of the Mormon founding, Evangelical counter- Mormons gather to distribute literature and attempt to dissuade pageant-goers from their Mormonism. The hugeness of the pageant and the smallness of the town displace Christianity as de facto center and make Mormonism the central religion. Cast to the periphery, counter-Mormons must attempt to reassert the centrality of Christianity. Counter-Mormons and Mormons also wrangle over control of terms. These “turf wars” over issues of doctrine are much more about power than doctrinal “purity”: who gets to authoritatively speak for Mormonism. Meanwhile, as Mormonism moves Christianward, this creates room for Mormon fundamentalism, as small groups of dissidents lay claim to Joseph Smith’s “original” Mormonism. Manti is home of the True and Living Church of Jesus Christ of Saints of the Last Days, a group that broke away from the Mormon Church in 1994 and considers the mainstream church apostate, offering a challenge to its dominance in this time and place. -

The Marrow of Human Experience

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2006 The Marrow of Human Experience William A. Wilson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the Folklore Commons, and the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Wilson, W. A., Rudy, J. T., & Call, D. (2006). The marrow of human experience: Essays on folklore. Logan, UT: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Marrow of Human Experience ESSAYS ON FOLKLORE William A. Wilson Edited by Jill Terry Rudy The Marrow of Human Experience The Marrow of Human Experience ! Essays on Folklore By William A. Wilson Edited by Jill Terry Rudy with the assistance of Diane Call Utah State University Press Logan, UT Copyright © 2006 Utah State University Press All rights reserved Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322–7800 www.usu.edu/usupress/ Manufactured in the United States of America Printed on acid-free paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wilson, William Albert. The marrow of human experience : essays on folklore / by William A. Wilson ; edited by Jill Terry Rudy with the assistance of Diane Call. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN-13: 978-0-87421-653-0 (pbk.) ISBN- 0-87421-545-5 (e-book) ISBN-10: 0-87421-653-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Folklore and nationalism. 2.