I Loved Thy Creation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George B. Seitz Motion Picture Stills, 1919-Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8h41trq No online items Finding Aid for the George B. Seitz motion picture stills, 1919-ca. 1944 Processed by Arts Special Collections Staff, pre-1999; machine-readable finding aid created by Julie Graham and Caroline Cubé; supplemental EAD encoding by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] ©2014 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the George B. PASC 31 1 Seitz motion picture stills, 1919-ca. 1944 Title: George B. Seitz motion picture stills Collection number: PASC 31 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 3.8 linear ft.(9 boxes) Date (bulk): Bulk, 1930-1939 Date (inclusive): ca. 1920-ca. 1942, ca. 1930s Abstract: George B. Seitz was an actor, screenwriter, and director. The collection consists of black and white motion picture stills representing 30-plus productions related to Seitz's career. Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Creator: Seitz, George B., 1888-1944 Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to UCLA Library Special Collections. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. -

The Apocalyptic Book List

The Apocalyptic Book List Presented by: The Post Apocalyptic Forge Compiled by: Paul Williams ([email protected]) As with other lists compiled by me, this list contains material that is not strictly apocalyptic or post apocalyptic, but that may contain elements that have that fresh roasted apocalyptic feel. Because I have not read every single title here and have relied on other peoples input, you may on occasion find a title that is not appropriate for the intended genre....please do let me know and I will remove it, just as if you find a title that needs to be added...that is appreciated as well. At the end of the main book list you will find lists for select series of books. Title Author 8.4 Peter Hernon 905 Tom Pane 2011, The Evacuation of Planet Earth G. Cope Schellhorn 2084: The Year of the Liberal David L. Hale 3000 Ad : A New Beginning Jon Fleetwood '48 James Herbert Abyss, The Jere Cunningham Acts of God James BeauSeigneur Adulthood Rites Octavia Butler Adulthood Rites, Vol. 2 Octavia E. Butler Aestival Tide Elizabeth Hand Afrikorps Bill Dolan After Doomsday Poul Anderson After the Blue Russel C. Like After the Bomb Gloria D. Miklowitz After the Dark Max Allan Collins After the Flames Elizabeth Mitchell After the Flood P. C. Jersild After the Plague Jean Ure After the Rain John Bowen After the Zap Michael Armstrong After Things Fell Apart Ron Goulart After Worlds Collide Edwin Balmer, Philip Wylie Aftermath Charles Sheffield Aftermath K. A. Applegate Aftermath John Russell Fearn Aftermath LeVar Burton Aftermath, The Samuel Florman Aftershock Charles Scarborough Afterwar Janet Morris Against a Dark Background Iain M. -

ATHABASCA UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY of CALGARY UNIVERSITY of LETHBRIDGE SONGWRITING in THERAPY by JOHN A. DOWNES a Final Project

ATHABASCA UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY UNIVERSITY OF LETHBRIDGE SONGWRITING IN THERAPY BY JOHN A. DOWNES A Final Project submitted to the Campus Alberta Applied Psychology: Counselling Initiative In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF COUNSELLING Alberta August 2006 i ii iii Abstract Songwriting addresses therapy on multiple levels: through the process, product, and experience of songwriting in the context of a therapeutic relationship. A literature review provides the background and rationale for writing a guide to songwriting in therapy. The resource guide illustrates 18 techniques of songwriting in therapy. Each technique includes details regarding salient features, clinical uses, client prerequisites, therapist skills, goals, media and roles, format, preparation required, procedures, data interpretation, and client/group-therapist dynamics. An ethical dilemma illustrates the need for caution when implementing songwriting in therapy. Examples of consent forms are included in the guide. The author concludes by reviewing what he has learned in the process of researching and writing the guide, and evaluates his research. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I – Songwriting in Therapy………………………………………….………..1 Rationale………………………………………………………………………….……...1 Identifying the Need…………………………………………………………….1 Creating a resource……………………………………………………..………2 Data analysis…………………………………………………………….………2 An ethical question…………………………………………………….………..3 Implications………………………………………………………………………3 Chapter II –Songwriting: A Useful Therapeutic -

Dissertation Baby

RELATIONAL NARRATIVES: CONSTRUCTING MEANING IN CONTEMPORARY LITERATURES IN FRENCH by Rebecca Loescher A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland March, 2017 Abstract The act of narrating permeates daily life: from the tales we tell about our identities to published works of fiction, narratives fundamentally shape human perception. With this in mind, Relational Narratives: Constructing Meaning in Contemporary Literatures in French explores narrative mode as a means for structuring innovative thought-models. Marrying close readings with socio-cultural analyses, it examines relational narrative modes in six works of prose published since the turn of the 1980s: François Bon’s Sortie d’usine (1982), Assia Djebar’s L’Amour, la fantasia (1985), Maryse Condé’s Traversée de la Mangrove (1989), Patrick Chamoiseau’s Texaco (1992), Koffi Kwahulé’s Babyface (2006), and Annie Ernaux’s Les Années (2008). Part One, on narrative voice and temporality, argues that relational narratives bring temporally divergent voices into a single space of resonance. Part Two turns to the portrayal of narrative truths, whether collective, individual, historical, or purely fabricated, as well as to the mixing of genres, which include autobiography, historical realism, testimony, ethnography, and the marvelous. I contend that truth in relational narratives is multiple and shifting, and requires that the reader actively construct meaning. Finally, Part Three examines the political implications of relational narration. First, I show that relational narratives remain fully grounded in specific socio-cultural contexts — or their lieu, the space from which Édouard Glissant contends relation becomes possible. -

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha E Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha_E_Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Runnin' (Trying To Live) 2Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3Oh!3 Feat. Katy Perry Starstrukk 3T Anything 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 5 Seconds of Summer She's Kinda Hot 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Seconds of Summer Hey Everybody 5 Seconds of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds of Summer Girls Talk Boys 5 Seconds of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds of Summer Amnesia 5 Seconds of Summer (Feat. Julia Michaels) Lie to Me 5ive When The Lights Go Out 5ive We Will Rock You 5ive Let's Dance 5ive Keep On Movin' 5ive If Ya Getting Down 5ive Got The Feelin' 5ive Everybody Get Up 6LACK Feat. J Cole Pretty Little Fears 7Б Молодые ветра 10cc The Things We Do For Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc I'm Mandy Fly Me 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc Donna 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 30 Seconds To Mars Rescue Me 30 Seconds To Mars Kings And Queens 30 Seconds To Mars From Yesterday 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent Feat. Eminem & Adam Levine My Life 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg and Young Jeezy Major Distribution 101 Dalmatians (Disney) Cruella De Vil 883 Nord Sud Ovest Est 911 A Little Bit More 1910 Fruitgum Company Simon Says 1927 If I Could "Weird Al" Yankovic Men In Brown "Weird Al" Yankovic Ebay "Weird Al" Yankovic Canadian Idiot A Bugs Life The Time Of Your Life A Chorus Line (Musical) What I Did For Love A Chorus Line (Musical) One A Chorus Line (Musical) Nothing A Goofy Movie After Today A Great Big World Feat. -

Women's Achieve Summit Richmond, VA October 15, 2019 Introduction

Women’s Achieve Summit Richmond, VA October 15, 2019 Introduction Queen Latifah, producer, actor, and musical performer Announcer: Good morning. Please give a warm Virginia welcome to our host and emcee, a multi-talented star who was a female hip hop pioneer, a Grammy and Emmy winner, and an Academy award nominee. The one, the only, Queen Latifah. Queen Latifah: Wow. You all was jamming. Woo. Thank you so much. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you everyone. Relax. Have a seat. We about to hangout all day. I saw you had my girl Missy Misdemeanor Elliot up there. So proud of her. Just talked to her the other day too, so. Thank you so much and thank you. Give it up for the house band, the Misbehaviors. They're going to be rocking with us all day. Please make yourself comfortable. Audience: I love you. Queen Latifah: Thank you. Thank you. Thank you. You got it. What a great sight to look out at 1400 women and one or two brave guys. I'm so happy to be here and be your host today. Today's summit is one of the signature events of the 2019 Commemoration American Evolution. American Evolution is the Commonwealth of Virginia's 400th anniversary of events in 1619 that still impact us today. All year, Virginia has been telling authentic stories of 400 years of democracy, diversity and opportunity in America. Women have not always been invited to participate in that democracy. Oh, but we in it now. And we are here to celebrate that today. -

The Triple Crown (1867-2019)

The Triple Crown (1867-2019) Kentucky Derby Winner Preakness Stakes Winner Belmont Stakes Winner Horse of the Year Jockey Jockey Jockey Champion 3yo Trainer Trainer Trainer Year Owner Owner Owner 2019 Country House War of Will Sir Winston Bricks and Mortar Flavien Prat Tyler Gaffalione Joel Rosario Maximum Security Bill Mott Mark Casse Mark Casse Mrs. J.V. Shields Jr., E.J.M. McFadden Jr. & LNJ Foxwoods Gary Barber Tracy Farmer 2018 Justify Justify Justify Justify Mike Smith Mike Smith Mike Smith Justify Bob Baffert Bob Baffert Bob Baffert WinStar Farm LLC, China Horse Club, Starlight Racing & Head of Plains Partners LLC WinStar Farm LLC, China Horse Club, Starlight Racing & Head of Plains Partners LLC WinStar Farm LLC, China Horse Club, Starlight Racing & Head of Plains Partners LLC 2017 Always Dreaming Cloud Computing Tapwrit Gun Runner John Velazquez Javier Castellano Joel Ortiz West Coast Todd Pletcher Chad Brown Todd Pletcher MeB Racing, Brooklyn Boyz, Teresa Viola, St. Elias, Siena Farm & West Point Thoroughbreds Bridlewood Farm, Eclipse Thoroughbred Partners & Robert V. LaPenta Klaravich Stables Inc. & William H. Lawrence 2016 Nyquist Exaggerator Creator California Chrome Mario Gutierrez Kent Desormeaux Irad Ortiz Jr. Arrogate Doug O’Neill Keith Desormeaux Steve Asmussen Big Chief Racing, Head of Plains Partners, Rocker O Ranch, Keith Desormeaux Reddam Racing LLC (J. Paul Reddam) WinStar Farm LLC & Bobby Flay 2015 American Pharoah American Pharoah American Pharoah American Pharoah Victor Espinoza Victor Espinoza Victor Espinoza American Pharoah Bob Baffert Bob Baffert Bob Baffert Zayat Stables LLC (Ahmed Zayat) Zayat Stables LLC (Ahmed Zayat) Zayat Stables LLC (Ahmed Zayat) 2014 California Chrome California Chrome Tonalist California Chrome Victor Espinoza Victor Espinoza Joel Rosario California Chrome Art Sherman Art Sherman Christophe Clement Steve Coburn & Perry Martin Steve Coburn & Perry Martin Robert S. -

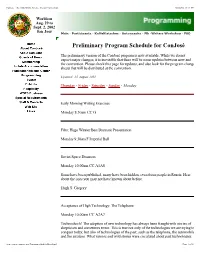

Preliminary Program Schedule for Conjosé

ConJose - the 60th World Science Fiction Convention 08/26/02 11:13 PM Worldcon Aug. 29 to Sept. 2, 2002 San José Main - Participants - KaffeKlatsches - Autographs - Filk -Writers Workshop - FAQ Preliminary Program Schedule for ConJosé The preliminary version of the ConJosé program is now available. While we do not expect major changes, it is inevitable that there will be some updates between now and the convention. Please check this page for updates, and also look for the program change sheets that will be distributed at the convention. Updated: 25 August 2002 Thursday - Friday - Saturday - Sunday - Monday Early Morning Writing Exercises Monday 8:30am CC G Film: Hugo Winner Best Dramatic Presentation Monday 9:30am F Imperial Ball Soviet Space Disasters Monday 10:00am CC A1A8 Some have been published, many have been hidden, even from people in Russia. Hear about the ones you may not have known about before. Hugh S. Gregory Acceptance of High Technology: The Telephone Monday 10:00am CC A2A7 Technoshock! The adoption of new technology has always been fraught with stories of skepticism and sometimes terror. This is true not only of the technologies we are trying to conquer today, but also of technologies of the past; such as the telephone, the automobile and the airplane. What rumors and wild stories were circulated about past technologies http://www.conjose.org/Program/scheduleMon.html Page 1 of 15 ConJose - the 60th World Science Fiction Convention 08/26/02 11:13 PM and how do they compare to the stories about today's technology? Vernor Vinge, Chris Garcia, Kevin P. -

The Triple Crown (1867-2020)

The Triple Crown (1867-2020) Kentucky Derby Winner Preakness Stakes Winner Belmont Stakes Winner Horse of the Year Jockey Jockey Jockey Champion 3yo Trainer Trainer Trainer Year Owner Owner Owner 2020 Authentic (Sept. 5, 2020) f-Swiss Skydiver (Oct. 3, 2020) Tiz the Law (June 20, 2020) Authentic John Velazquez Robby Albarado Manny Franco Authentic Bob Baffert Kenny McPeek Barclay Tagg Spendthrift Farm, MyRaceHorse Stable, Madaket Stables & Starlight Racing Peter J. Callaghan Sackatoga Stable 2019 Country House War of Will Sir Winston Bricks and Mortar Flavien Prat Tyler Gaffalione Joel Rosario Maximum Security Bill Mott Mark Casse Mark Casse Mrs. J.V. Shields Jr., E.J.M. McFadden Jr. & LNJ Foxwoods Gary Barber Tracy Farmer 2018 Justify Justify Justify Justify Mike Smith Mike Smith Mike Smith Justify Bob Baffert Bob Baffert Bob Baffert WinStar Farm LLC, China Horse Club, Starlight Racing & Head of Plains Partners LLC WinStar Farm LLC, China Horse Club, Starlight Racing & Head of Plains Partners LLC WinStar Farm LLC, China Horse Club, Starlight Racing & Head of Plains Partners LLC 2017 Always Dreaming Cloud Computing Tapwrit Gun Runner John Velazquez Javier Castellano Joel Ortiz West Coast Todd Pletcher Chad Brown Todd Pletcher MeB Racing, Brooklyn Boyz, Teresa Viola, St. Elias, Siena Farm & West Point Thoroughbreds Bridlewood Farm, Eclipse Thoroughbred Partners & Robert V. LaPenta Klaravich Stables Inc. & William H. Lawrence 2016 Nyquist Exaggerator Creator California Chrome Mario Gutierrez Kent Desormeaux Irad Ortiz Jr. Arrogate Doug -

Believarexic.Pdf

Young adult / fiction www.peachtree-online.com be • bulimarexic believarexic n. bu be • lim • liev • a • rex • ic liev Someone with an eating human disorder marked by an alternation between intense craving for and aversion ood belief in oneself. • to f a • rex H “Compelling and authentic, this story is impossible to put down. Believarexic is a raw, memorable reading experience.” • —Booklist ic “A powerful story of healing and self-acceptance.” —Kirkus Reviews 978-1-68263-007-5 $9.95 be•liev•a•rex•ic Believarexic TPB cover for BEA.indd 1 4/20/17 12:55 PM be•liev•a•rex•ic For Sam— We all have monsters. May yours be a friendly, loyal luck dragon who will fly you in the direction of your dreams. Published by PEACHTREE PUBLISHERS 1700 Chattahoochee Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30318-2112 www.peachtree-online.com Text © 2015 by J. J. Johnson All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Design and composition by Nicola Simmonds Carmack Printed May 2015 in Harrisonburg, VA, by R. R. Donnelley 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 First Edition Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Johnson, J. J., 1973- Believarexic / JJ Johnson. pages cm ISBN 978-1-56145-771-7 Summary: An autobiographical novel in which fifteen-year-old Jennifer Johnson con- vinces her parents to commit her to the Eating Disorders Unit of an upstate New York psychiatric hospital in 1988, where the treatment for her bulimia and anorexia is not what she expects. -

NATIONAL Cf'ictorial SHOW ISSUE

50¢ SEPTEMBER,1962 ORSE NATIONALCf'ictorial SHOWISSUE WASEEKA'S NOCTURNE Sire: Starfire Dam: Upwey Benn Quietude Winner A.H.S.A. High Score Award 1960 - 1961 Junior Champion Harness Horse National Mor- gan Show, 1957 Champion Saddle Horse National Morgan Show 1959 - 1960 - 1961 Shown consistently since 1957 at all major shows in the east. Never out of the ribbons having already acquired in the '61 season - The over Blue and Championship ribbons at "Rhode Island and Providence Plantation" Horse Show "Pequot Benefit Horse Show" "Children's Services" Horse Show "Great Barrington" Horse Show "Medfield P.H.A. Horse Show" "Barre Horse Show", Essex Jct., Woodstock , Vt. With this super show career this Staltion is very proud to say it looks as if . WASEEKA'S THEME SONG Sire: Waseeka 's Nocturne Dam: Mannequin Winner: Mares & Geldings Three Years Old Under Saddle National Morgan Show - 1962 Mares Three Years Old, National Morgan Show Junior Champion Mare, National Morgan Show GRAND CHAMPION MARE, National Morgan Show WASEEKA FARM, ASHLAND, MASS. MRS. D. D. POWER - MR. & MRS. E. KEENEANNIS JOHN J. LYOON Owners Trainer PARADE 10138 National Grand Champion Stallion 1955 National Reserve Champion Saddle Horse National Reserve Champion Harness Horse First in Combination and Harness Pairs several times PARADE SIRED Panorama: 1962 National Champ ion Harness Horse Bay State Estrelita : 1962 Reserve Champion Mare Broadwall St. Pat: Grand Champion Stallion Pacific North West 1962 Broadwall Brigadier : Grand Champion Stallion and winner of Get of Sire Class, 1962, Estes Park, Colorado. We have sons and daughters for sale - reasonable. It gives us great satisfaction to see so many Broadtvall horsej in tlze ribbons in the pleasure classes. -

Loscon 34 Program Book

LosconLoscon 3434 WelcomeWelcome to the LogbookLogbook of the “DIG”“DIG” LAX Marriott November 23 - 25, 2007 Robert J. Sawyer Author Guest Theresa Mather Artist Guest Capt. David West Reynolds Fan Guest Dr. James Robinson Music Guest 1 2 Table of Contents Anime .................................. Pg 68 Kids’ Night Out ..................... Pg 63 Art Show .............................. Pg 66 Listening Lounge .................. Pg 71 Awards Masquerade .......................... Pg 59 Evans-Freehafer ................ Pg 56 Members List ................. Pg 75-79 Forry ................................. Pg 57 Office / Lost & Found .......... Pg 71 Rotsler .............................. Pg 58 Photography/Videotape Policies .... Pg 70 Autographs .......................... Pg 73 Programming Panels ....... Pg 38-47 Bios Regency Dancing .................. Pg 62 Author Guest of Honor .........Pg 8-11 Registration .......................... Pg 71 Artist Guest of Honor ........ Pg 12-13 Room Parties ........................ Pg 63 Music Guest of Honor ........ Pg 16-17 Security Fan Guest of Honor ................. Pg 14 Rules & Regulations ..... Pg 70,73 Program Guests ........... Pg 30-37 No Smoking Policy ............. Pg 73 Blood Drive ........................... Pg 53 Weapons Policy ........... Pg 70,73 Chair’s Message .................. Pg 4-5 Special Needs ....................... Pg 60 Children’s Programming ........ Pg 68 Special Stories Committee & Staff ............. Pg 6-7 Peking Man .................. Pg 18-22 Computer Lounge ...............