Dissertation Baby

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Triple Crown (1867-2019)

The Triple Crown (1867-2019) Kentucky Derby Winner Preakness Stakes Winner Belmont Stakes Winner Horse of the Year Jockey Jockey Jockey Champion 3yo Trainer Trainer Trainer Year Owner Owner Owner 2019 Country House War of Will Sir Winston Bricks and Mortar Flavien Prat Tyler Gaffalione Joel Rosario Maximum Security Bill Mott Mark Casse Mark Casse Mrs. J.V. Shields Jr., E.J.M. McFadden Jr. & LNJ Foxwoods Gary Barber Tracy Farmer 2018 Justify Justify Justify Justify Mike Smith Mike Smith Mike Smith Justify Bob Baffert Bob Baffert Bob Baffert WinStar Farm LLC, China Horse Club, Starlight Racing & Head of Plains Partners LLC WinStar Farm LLC, China Horse Club, Starlight Racing & Head of Plains Partners LLC WinStar Farm LLC, China Horse Club, Starlight Racing & Head of Plains Partners LLC 2017 Always Dreaming Cloud Computing Tapwrit Gun Runner John Velazquez Javier Castellano Joel Ortiz West Coast Todd Pletcher Chad Brown Todd Pletcher MeB Racing, Brooklyn Boyz, Teresa Viola, St. Elias, Siena Farm & West Point Thoroughbreds Bridlewood Farm, Eclipse Thoroughbred Partners & Robert V. LaPenta Klaravich Stables Inc. & William H. Lawrence 2016 Nyquist Exaggerator Creator California Chrome Mario Gutierrez Kent Desormeaux Irad Ortiz Jr. Arrogate Doug O’Neill Keith Desormeaux Steve Asmussen Big Chief Racing, Head of Plains Partners, Rocker O Ranch, Keith Desormeaux Reddam Racing LLC (J. Paul Reddam) WinStar Farm LLC & Bobby Flay 2015 American Pharoah American Pharoah American Pharoah American Pharoah Victor Espinoza Victor Espinoza Victor Espinoza American Pharoah Bob Baffert Bob Baffert Bob Baffert Zayat Stables LLC (Ahmed Zayat) Zayat Stables LLC (Ahmed Zayat) Zayat Stables LLC (Ahmed Zayat) 2014 California Chrome California Chrome Tonalist California Chrome Victor Espinoza Victor Espinoza Joel Rosario California Chrome Art Sherman Art Sherman Christophe Clement Steve Coburn & Perry Martin Steve Coburn & Perry Martin Robert S. -

The Triple Crown (1867-2020)

The Triple Crown (1867-2020) Kentucky Derby Winner Preakness Stakes Winner Belmont Stakes Winner Horse of the Year Jockey Jockey Jockey Champion 3yo Trainer Trainer Trainer Year Owner Owner Owner 2020 Authentic (Sept. 5, 2020) f-Swiss Skydiver (Oct. 3, 2020) Tiz the Law (June 20, 2020) Authentic John Velazquez Robby Albarado Manny Franco Authentic Bob Baffert Kenny McPeek Barclay Tagg Spendthrift Farm, MyRaceHorse Stable, Madaket Stables & Starlight Racing Peter J. Callaghan Sackatoga Stable 2019 Country House War of Will Sir Winston Bricks and Mortar Flavien Prat Tyler Gaffalione Joel Rosario Maximum Security Bill Mott Mark Casse Mark Casse Mrs. J.V. Shields Jr., E.J.M. McFadden Jr. & LNJ Foxwoods Gary Barber Tracy Farmer 2018 Justify Justify Justify Justify Mike Smith Mike Smith Mike Smith Justify Bob Baffert Bob Baffert Bob Baffert WinStar Farm LLC, China Horse Club, Starlight Racing & Head of Plains Partners LLC WinStar Farm LLC, China Horse Club, Starlight Racing & Head of Plains Partners LLC WinStar Farm LLC, China Horse Club, Starlight Racing & Head of Plains Partners LLC 2017 Always Dreaming Cloud Computing Tapwrit Gun Runner John Velazquez Javier Castellano Joel Ortiz West Coast Todd Pletcher Chad Brown Todd Pletcher MeB Racing, Brooklyn Boyz, Teresa Viola, St. Elias, Siena Farm & West Point Thoroughbreds Bridlewood Farm, Eclipse Thoroughbred Partners & Robert V. LaPenta Klaravich Stables Inc. & William H. Lawrence 2016 Nyquist Exaggerator Creator California Chrome Mario Gutierrez Kent Desormeaux Irad Ortiz Jr. Arrogate Doug -

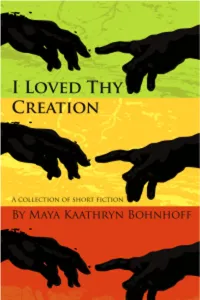

I Loved Thy Creation

I Loved Thy Creation A collection of short fiction by Maya Kaathryn Bohnhoff O SON OF MAN! I loved thy creation, hence I created thee. Bahá’u’lláh Copyright 2008, Maya Kaathryn Bohnhoff and Juxta Publishing Limited. www.juxta.com. Cover image "© Horvath Zoltan | Dreamstime.com" ISBN 978-988-97451-8-9 This book has been produced with the consent of the original authors or rights holders. Authors or rights holders retain full rights to their works. Requests to reproduce the contents of this work can be directed to the individual authors or rights holders directly or to Juxta Publishing Limited. Reproduction of this book in its current form is governed by the Juxta Publishing Books for the World license outlined below. This book is released as part of Juxta Publishing's Books for the World program which aims to provide the widest possible access to quality Bahá'í-inspired literature to readers around the world. Use of this book is governed by the Juxta Publishing Books for the World license: 1. This book is available in printed and electronic forms. 2. This book may be freely redistributed in electronic form so long as the following conditions are met: a. The contents of the file are not altered b. This copyright notice remains intact c. No charges are made or monies collected for redistribution 3 The electronic version may be printed or the printed version may be photocopied, and the resulting copies used in non-bound format for non-commercial use for the following purposes: a. Personal use b. Academic or educational use When reproduced in this way in printed form for academic or educational use, charges may be made to recover actual reproduction and distribution costs but no additional monies may be collected. -

NATIONAL Cf'ictorial SHOW ISSUE

50¢ SEPTEMBER,1962 ORSE NATIONALCf'ictorial SHOWISSUE WASEEKA'S NOCTURNE Sire: Starfire Dam: Upwey Benn Quietude Winner A.H.S.A. High Score Award 1960 - 1961 Junior Champion Harness Horse National Mor- gan Show, 1957 Champion Saddle Horse National Morgan Show 1959 - 1960 - 1961 Shown consistently since 1957 at all major shows in the east. Never out of the ribbons having already acquired in the '61 season - The over Blue and Championship ribbons at "Rhode Island and Providence Plantation" Horse Show "Pequot Benefit Horse Show" "Children's Services" Horse Show "Great Barrington" Horse Show "Medfield P.H.A. Horse Show" "Barre Horse Show", Essex Jct., Woodstock , Vt. With this super show career this Staltion is very proud to say it looks as if . WASEEKA'S THEME SONG Sire: Waseeka 's Nocturne Dam: Mannequin Winner: Mares & Geldings Three Years Old Under Saddle National Morgan Show - 1962 Mares Three Years Old, National Morgan Show Junior Champion Mare, National Morgan Show GRAND CHAMPION MARE, National Morgan Show WASEEKA FARM, ASHLAND, MASS. MRS. D. D. POWER - MR. & MRS. E. KEENEANNIS JOHN J. LYOON Owners Trainer PARADE 10138 National Grand Champion Stallion 1955 National Reserve Champion Saddle Horse National Reserve Champion Harness Horse First in Combination and Harness Pairs several times PARADE SIRED Panorama: 1962 National Champ ion Harness Horse Bay State Estrelita : 1962 Reserve Champion Mare Broadwall St. Pat: Grand Champion Stallion Pacific North West 1962 Broadwall Brigadier : Grand Champion Stallion and winner of Get of Sire Class, 1962, Estes Park, Colorado. We have sons and daughters for sale - reasonable. It gives us great satisfaction to see so many Broadtvall horsej in tlze ribbons in the pleasure classes. -

String of Burglaries Possibly Tied to Local Man

5 Day Forecast 5/14 a.m 5/14 p.m. 5/15 a.m. 5/15 p.m. 5/16 a.m. 5/16 p.m 5/17 The Madill Record ‘In the Arms of Lake TTexoma’exoma’ Vol. 125 — Number 46 Madill, Marshall CountyCounty,, OK 73446 — ThursdayThursday,, May 14, 2020 14 Pages in 2 Sections — $1 String of burglaries possibly tied to local man By Shalene White entering. Hanks and Watson located First-Degree Robbery. The suspect [email protected] the initial suspect, and questioned was cleared for any active warrants. him on his whereabouts during the Because Marques was unable to hear A string of recent burglaries could approximated time of the crime. The the prior conviction, and Whitney had possibly be tied to a local Kingston suspect informed Hanks that he was no outstanding warrants, the officer man. Nathan Whitney, a 27-year-old asleep, but somebody knocked on his drove Whitney back to his residence male from Kingston was recently ar- door at approximately 5:30 a.m. He in the 400 block of South Kemp Street. rested after an on-going investigation said he did not recognize the voice, Once Marques returned to the led police to his front door. so he pretended to be asleep. scene of the crime, Country Kitchen, The investigation began on May 6 Realizing that part of the inves- he noticed severe damage to the door when Kingston Officer Dakota Hanks tigation had hit a dead end, the frame to the employee entrance. The was flagged down by the owners of officers left. -

U.S. Copyright Renewals, 1966 January - June

U.S. Copyright Renewals, 1966 January - June By U.S. Copyright Office English A Doctrine Publishing Corporation Digital Book This book is indexed by ISYS Web Indexing system to allow the reader find any word or number within the document. page images supplied by the Universal Library Project at Carnegie Mellon University. <pb id='001.png' n='1966h1/A/1113' /> RENEWAL REGISTRATIONS A list of books, pamphlets, serials, and contributions to periodicals for which renewal registrations were made during the period covered by this issue. Arrangement is alphabetical under the name of the author or issuing body or, in the case of serials and certain other works, by title. Information relating to both the original and the renewal registration is included in each entry. References from the names of renewal claimants, joint authors, editors, etc. and from variant forms are interfiled. AARON, MICHAEL. MacLachlan-Aaron piano course book ABBOTT, AUSTIN. Forms of pleading in actions for legal ABBOTT, DAISY T. The northern garden week by week. ABBOTT, E. C. We pointed them north; recollections ABBOTT, MRS. E. C. We pointed them north. SEE ABBOTT, FRANK A. Singing shadows. SEE Abbott, Jane. ABBOTT, GRACE. Work accidents to minors in Illinois. ABBOTT, JANE. Singing shadows. © 23Jun38; A119316. ABBOTT, THOMSON. The northern garden week by week. ABBOTT NEW YORK DIGEST, CONSOLIDATED EDITION. Cumulative pamphlet. © West Pub. Co. & Lawyers Co-operative Pub. Co. (PWH) Dec38. © 7Dec38; A124907. 5Jan66; Mar39. © 20Mar39; A129167. 4Apr66; Doctrine Publishing Corporation Digital Book Page 1 Jun39. © 26Jun39; A130504. <pb id='002.png' /> ABBOTT NEW YORK DIGEST, CONSOLIDATED EDITION. 1938 cumulative annual pocket parts. -

2008 International List of Protected Names

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities _________________________________________________________________________________ _ 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Avril / April 2008 Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : ) des gagnants des 33 courses suivantes depuis leur ) the winners of the 33 following races since their création jusqu’en 1995 first running to 1995 inclus : included : Preis der Diana, Deutsches Derby, Preis von Europa (Allemagne/Deutschland) Kentucky Derby, Preakness Stakes, Belmont Stakes, Jockey Club Gold Cup, Breeders’ Cup Turf, Breeders’ Cup Classic (Etats Unis d’Amérique/United States of America) Poule d’Essai des Poulains, Poule d’Essai des Pouliches, Prix du Jockey Club, Prix de Diane, Grand Prix de Paris, Prix Vermeille, Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe (France) 1000 Guineas, 2000 Guineas, Oaks, Derby, Ascot Gold Cup, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, St Leger, Grand National (Grande Bretagne/Great Britain) Irish 1000 Guineas, 2000 Guineas, Derby, Oaks, Saint Leger (Irlande/Ireland) Premio Regina Elena, Premio Parioli, Derby Italiano, Oaks (Italie/Italia) -

2009 International List of Protected Names

Liste Internationale des Noms Protégés LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities __________________________________________________________________________ _ 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] 2 03/02/2009 International List of Protected Names Internet : www.IFHAonline.org 3 03/02/2009 Liste Internationale des Noms Protégés La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : ) des gagnants des 33 courses suivantes depuis leur ) the winners of the 33 following races since their création jusqu’en 1995 first running to 1995 inclus : included : Preis der Diana, Deutsches Derby, Preis von Europa (Allemagne/Deutschland) Kentucky Derby, Preakness Stakes, Belmont Stakes, Jockey Club Gold Cup, Breeders’ Cup Turf, Breeders’ Cup Classic (Etats Unis d’Amérique/United States of America) Poule d’Essai des Poulains, Poule d’Essai des Pouliches, Prix du Jockey Club, Prix de Diane, Grand Prix de Paris, Prix Vermeille, Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe (France) 1000 Guineas, 2000 Guineas, Oaks, Derby, Ascot Gold Cup, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, St Leger, Grand National (Grande Bretagne/Great Britain) Irish 1000 Guineas, 2000 Guineas, -

Globalization, Identity Formation and Hegemony in the Baha'i

Bates College SCARAB Honors Theses Capstone Projects Spring 5-2016 Drops of One Ocean: Globalization, Identity Formation and Hegemony in the Baha'i Communities of Samoa, the Netherlands, Latvia, and Lithuania Detmer Yens Kremer Bates College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses Recommended Citation Kremer, Detmer Yens, "Drops of One Ocean: Globalization, Identity Formation and Hegemony in the Baha'i Communities of Samoa, the Netherlands, Latvia, and Lithuania" (2016). Honors Theses. 163. http://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses/163 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects at SCARAB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Drops of One Ocean Globalization, Identity Formation and Hegemony in the Baha’i Communities of Samoa, the Netherlands, Latvia, and Lithuania An Honors Thesis Presented To The Faculty of the Department of Anthropology Bates College In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts By Detmer Yens Kremer Lewiston, Maine March 28, 2016 i Leave pake, Jo koene dizze wurden net lêze. Ik haw se skreaun yn in taal dy't jo net praten koe, mar ik hoopje dat jo grutsk binne. Miskien kin immen it foar jo fertale. Ik sei ‘t net faak genôch, mar ik hâld fan dy (I dedicate my thesis to my grandfather, a man who taught me to work hard and be proud of who I am. A kind man with his own stubborn ideas and sense of right and wrong. -

Dorothy Baker, a Photograph Taken in the Late 1930S, and One of Her Favorites

Champion Builder Books are a series of biographies about indi- viduals who have been instrumental in helping the North Ameri- can Bahá í community fulfill its destiny—in the words of Shoghi Effendi, the Guardian of the Bahá'í Faith—as “the champion builders of Bahá'u'lláh's rising World Order.” Other Champion Builder Books: To Move the World: Louis Gregory and the Advancement of Racial Unity in America by Gayle Morrison Martha Root: Lioness at the Threshold by M. R. Garis Zikrullah Khadem, The Itinerant Hand of the Cause of God: With Love by Javidukht Khadem ii Dorothy Baker, a photograph taken in the late 1930s, and one of her favorites. iii iv THE LIFE OF Dorothy Baker “Is it ever possible,” they ask, “for copper to be transmuted into gold?” Say, Yes, by my Lord, it is possible.—Bahá’u’lláh BY DOROTHY FREEMAN GILSTRAP Researched by Louise B. Mathias Bahá’í Publishing Trust Wilmette, Illinois v Bahá’í Publishing Trust, Wilmette, Illinois 60091-2844 Copyright © 1999 by Dorothy Freeman Gilstrap All Rights Reserved. Published 1999 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data. Freeman, Dorothy. 1951– From Copper to Gold: the life of Dorothy Baker / by Dorothy Freeman Gilstrap; researched by Louise B. Matthias. — [2nd ed.] p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-87743-255-4 1. Baker. Dorothy. 1898-1954. 2. Hands of the Cause of God— Biography. 3. Bahais—Biography. I. Title BP395.B35F74 1998 297.9’3’09—dc21 [B] 98-31611 CIP vi This book is dedicated, as was the life of Dorothy Baker, to the Guardian of the Bahá’í Faith, Shoghi Effendi whose vision for humankind continues to inspire in myriad hearts the longing to give their all to the Cause for which he so nobly and selflessly lived. -

Allerton Park Institute, No. 14 1967

020.715 no, U cop, 3 TRENDS IN AMERICAN PUBLISHING Allerton Park Institute The person charging this material is re- sponsible for its return on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutilation, and underlining of books are reasons for disciplinary action and may result in dismissal from the University. University of Illinois Library L161 O-1096 ALLERTON PARK INSTITUTE Number Fourteen TRENDS IN AMERICAN PUBLISHING Papers presented at an Institute conducted by the University of Illinois Graduate School of Library Science November 5-8, 1967 Edited by Kathryn Luther Henderson University of Illinois Graduate School of Library Science Champaign, Illinois Copyright 1968 by Kathryn Luther Henderson VOLUMES IN THIS SERIES The School Library Supervisor (Allerton Park Institute No. 1), 1956. $2 paper; $3 cloth. The Nature and Development of the Library Collection (No. 3), 1957. $2 paper; $3 cloth. The Library as a Community Information Center (No. 4), 1959. $2 paper; $3 cloth. The Role of Classification in the Modern American Library (No. 6), 1959. $2 paper; $3 cloth. Collecting Science Literature for General Reading (No. 7), 1960. $2 paper; $3 cloth. The Impact of the Library Services Act: Progress and Potential (No. 8), 1961. $2 paper; $3 cloth. Selection and Acquisition Procedures in Medium-Sized and Large Li- braries (No. 9), 1963. $2 paper; $3 cloth. The School Library Materials Center: Its Resources and Their Uti- lization (No. 10), 1964. $2 paper; $3 cloth. University Archives (No. 11), 1965. $2 paper; $3 cloth. The Changing Environment for Library Services in the Metropolitan Area (No. 12), 1966. $2 paper; $3 cloth. -

The Unfoldment of World Civilization

THE UNFOLDMENT OF WORLD CIVILIZATION by Shoghi Effendi This interactive document was designed, researched and published as a pdf by Duane K. Troxel [email protected] Rev09-16-04 Amatu’l-Bahá Rúhíyyih Khánum’s Comments on “The Unfoldment of World Civilization” n 1936 he [Shoghi Effendi] wrote The Unfoldment of World Civilization; once again, as he so often did, Shoghi Effendi links this to the passing of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. It was a further exposition of the state Iof the world, the rapid political, moral and spiritual decline evident in it, the weakening of both Christianity and Islam, the dangers humanity in its heedlessness was running, and the strong, divine, hopeful remedy the teachings of Bahá’u’lláh had to offer. Important and educative as these wonderful letters of the Guardian were they provided, in their wealth of apposite quotations from Bahá’u’lláh’s own words which the Guardian had translated and lavishly cited, spiritual sustenance for the believers, for we know that the World of the Manifestation of God is the food of the soul. They also contained innumerable beautifully translated passages from the beloved Master’s Tablets. All this bounty the Guardian spread for the believers in feast after feast, nourished them and raised up a new strong generation of servants in the Faith. His words fired their imagination, challenged them to rise to new heights, drove their roots deeper in the fertile soil of the Cause. It is really during the 1930’s that one sees a change manifest in Shoghi Effendi’s writings. With the rapier of his pen in hand he now stands forth revealed as a giant.