ATHABASCA UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY of CALGARY UNIVERSITY of LETHBRIDGE SONGWRITING in THERAPY by JOHN A. DOWNES a Final Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

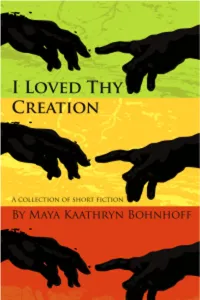

I Loved Thy Creation

I Loved Thy Creation A collection of short fiction by Maya Kaathryn Bohnhoff O SON OF MAN! I loved thy creation, hence I created thee. Bahá’u’lláh Copyright 2008, Maya Kaathryn Bohnhoff and Juxta Publishing Limited. www.juxta.com. Cover image "© Horvath Zoltan | Dreamstime.com" ISBN 978-988-97451-8-9 This book has been produced with the consent of the original authors or rights holders. Authors or rights holders retain full rights to their works. Requests to reproduce the contents of this work can be directed to the individual authors or rights holders directly or to Juxta Publishing Limited. Reproduction of this book in its current form is governed by the Juxta Publishing Books for the World license outlined below. This book is released as part of Juxta Publishing's Books for the World program which aims to provide the widest possible access to quality Bahá'í-inspired literature to readers around the world. Use of this book is governed by the Juxta Publishing Books for the World license: 1. This book is available in printed and electronic forms. 2. This book may be freely redistributed in electronic form so long as the following conditions are met: a. The contents of the file are not altered b. This copyright notice remains intact c. No charges are made or monies collected for redistribution 3 The electronic version may be printed or the printed version may be photocopied, and the resulting copies used in non-bound format for non-commercial use for the following purposes: a. Personal use b. Academic or educational use When reproduced in this way in printed form for academic or educational use, charges may be made to recover actual reproduction and distribution costs but no additional monies may be collected. -

Generational Consciousness in the Contemporary Novel

“Until the Thousand and First Generation”: Generational Consciousness in the Contemporary Novel by Gavin G. Spence A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Auburn, Alabama May 9, 2011 Keywords: Generations, tropes, phenomenology, historicism, contemporary novel Copyright 2011 by Gavin Gregory Spence Approved by Marc Silverstein, Chair, Professor of English Miriam Marty Clark, Professor of English Sunny Stalter, Assistant Professor of English Charles Israel, Associate Professor of History Abstract Generations, by their nature, stand at the crossroads of broad, collective experience (dividing national history into distinct decades) and personal experience (separating an entire lifespan into life phases). More than merely a commonplace phenomenon, each successive generation offers a dynamic structure that connects self to other, family to nation-state, and collective experience to historical time. This study examines the role that generations play in four contemporary novels and one novella: Ian McEwan’s Atonement, Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children, Jhumpa Lahiri’s Hema and Kaushik, Don DeLillo’s Underworld, and Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. Despite evident stylistic and structural differences, each work foregrounds generational members who confront profound crises of historical disruption and existential dislocation. Collectively, these works are cast against the backdrop of three national contexts shaped by the legacies of post- imperialism—America, England, and India—all of which have endured profound demographic changes from within and without their established borders. This requires a closer consideration of the particular communities out of which authors emerge and the specific issues of cultural conflict and adaptation that these authors address in their works. -

League' S Invitation Accepted by Hitler

cas TWELVS MONDAY, MARCH 18, 1^ 8. fflattr^fgjgfer gttrttftig I r m l d AVRRAGB DAH.T OntCULA'nOM THE WKATHKR for the Month et rebmary, IRS8 Foreout of O. 8. Weather Dunui. Seventy members of St Bridget's ■ Bnitferd Holy Name Society attended the 8 ABOUT TOWN o'clock mass yesterday morning and . \ received communion. St. Patrick *8 OM Your 5 , 7 9 3 ' Bala Mid Mlghtly wniiasr to- I tn . C T^Alllscm, of 896 East SPRING FLOWBR8 Mvnheg of tfee Aadit nlfhti Wednesday, rain poMdbly changing to nmw and much colder. tSenter atr«et, and Mias Margaret Mrs. Cecilia Zanlungo, of 25 Night FRESH Bofeuo of dreoUtloa. B. Hi^elBOD of 48 Russell strMt, BUdiidge street, was surprised last t M J W H A U CORK MANCHESTER - A CITY OF VILLAGE (HARM HlUieliester, have been guests at the night when about 60 of her relatives ■ Prom the Grower* Uriooln Hotel, New York aty. m a n c h i s t e r Co n h * « and friends called at her home to TONIGHT (UaMllled AdverttMag on P ag. IK). help her celebrate her birthday. .ANDERSON VOL. LV., NO. 143. MANCHESTER, CONN., TUESDAY, MARCH 17, 1936. (TWELVE PAGES) PRICE THREE CBNTE . NJanaes T. Pascoe of Watkins Games were played and Italian GREENHOUSES Btothem will give an Informal talk songs sung. A special feature of St. Bridget’s 158 Eldrtdge St. Self Serve and Health Market ana evmlng at the regular month the program was the lap dances Phone 8486 ly meeting of the Mother's Club of executed by Miss Lillian Naretto. -

Cal Tjader Warm Wave Mp3, Flac, Wma

Cal Tjader Warm Wave mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz / Latin Album: Warm Wave Country: US Released: 1964 Style: Easy Listening, Latin Jazz MP3 version RAR size: 1282 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1814 mb WMA version RAR size: 1926 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 840 Other Formats: MP4 RA APE AAC AU DMF RA Tracklist A1 Where Or When 2:47 A2 Violets For Your Furs 3:02 A3 People 2:31 A4 Poor Butterfly 2:13 A5 This Time The Dream's On Me 1:57 A6 Ev'ry Time We Say Goodbye 2:44 B1 I'm Old Fashioned 2:28 B2 The Way You Look Tonight 3:05 B3 Just Friends 2:18 B4 Sunset Blvd. 2:35 B5 Passé 2:40 Companies, etc. Manufactured By – Capitol Records, Inc. Credits Arranged By, Conductor – Claus Ogerman Bass – George Duvivier Drums – Ed Shaughnessy Engineer – Phil Ramone, Rudy Van Gelder Engineer [Director] – Val Valentin Guitar – Jim Raney*, Kenny Burrell Percussion – Willie Rodriguez Piano – Bernie Leighton, Hank Jones, Patti Bown Producer – Creed Taylor Strings – Alan Shulman, Charles McCracken, Gene Orloff, George Ockner, Harry Glickman, Harry Lookofsky, Julius Held, Teo Kruczek*, Lewis Eley, Louis Haber, Lucien Schmidt*, Maurice Brown, Morris Stonzek, Paul Gershman, Paul Winter, Raoul Poliakin, Sid Edwards, Sylvan Shulman Tenor Saxophone – Jerome Richardson, Seldon Powell Vibraphone – Cal Tjader Notes Recorded May 8, 11 & 13, 1964 at A&R Studios, New York City, and June 8, 1964 at Van Gelder Studios, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Cal Warm Wave (LP, V6-8585 Verve Records V6-8585 -

PSYCHOANALYST Quarterly Magazine of the American Psychoanalytic Association

the WINTER/SPRING 2014 AMERICAN Volume 48, No. 1 PSYCHOANALYST Quarterly Magazine of The American Psychoanalytic Association Story Tellers INSIDE TAP… Bob Pyles Election Results ....... 4 Once upon a very, very long time in human The answer is none. If you want to know history, the storyteller was “the keeper of the what this is all about, go find the sickest per- National Meeting keys” in terms of human culture and expe- son on the ward and sit with him or her for rience. We have gradually departed from as long as you can stand it.” Semrad went on, in NYC ......... 8 –13 those roots and in so doing have certainly “What you have to understand is that what lost our “mind” and perhaps our soul as well. may seem to be bizarre symptoms to you Sixth Annual My first experience in the art of the mas- do not seem at all bizarre to them. In fact, Art Exhibit ........ 14 ter storyteller was when I had the good they have evolved these symptoms as a way fortune to have William Faulkner as a writer- of coping with impossible family situations. Sovereign Right in-residence during my years at the Uni- These symptoms represent a creative adap- to Privacy ........ 21 versity of Virginia. The first book we were tive endeavor. They are a work of art as assigned was The Sound and the Fury. The first much as any other work of art. Your job, and 90 pages of this remarkable book consist of your only job, is to appreciate all these won- Annual Meeting what is quite literally free association in the derful stories you are going to be hearing.” in Chicago ...... -

Lew TABACKIN: Tatsuya TAKAHASHI

This discography is automatically generated by The JazzOmat Database System written by Thomas Wagner For private use only! ------------------------------------------ Lew TABACKIN: "Lew Tabackin" Lew Tabackin -ts,fl; Bob Dougherty -b; Bill Goodwin -d; recorded December 19, 1974 in Tokyo 11925 BYE BYE BLUES 7.22 RCA 6271 11926 SOLILOQUI 6.00 --- 21816 COME RAIN OR COME SHINE 7.36 --- 21817 MORNING 6.12 --- 21818 HOW DEEP IS THE OCEAN 5.52 --- 21821 LET THE TAPE ROLL 5.42 --- Lew Tabackin -ts; recorded December 19, 1974 in Tokyo 21822 GHOST OF A CHANCE 5.52 --- "Dual Nature" Lew Tabackin -fl,afl,ts[2]; Don Friedman -p; Bob Daugherty -b; Shelly Manne -d, perc; recorded August 31 and September 03, 1976 in Hollywood 69549 EUTERPE 7.15 Empathy EMP1001 69550 YELLOW IS MEOOW 5.48 --- 69551 OUT OF THIS WORLD 9.40 --- 69552 NO DUES BLUES (2) 9.22 --- 69553 MY IDEAL (2) 6.52 --- 69554 RUSSIAN LULLABY (2) 5.47 --- "Trackin'" Lew Tabackin -ts,fl; Toshiko Akiyoshi -p; Bob Daugherty -b; Shelly Manne -d; recorded September 03, 1976 in Hollywood 17075 I'M ALL SMILES 6.35 RCA RDC-3 17076 COTTON TAIL 5.49 --- 17077 TRACKIN' 6.16 --- 17078 SUMMERTIME 4.42 --- "Rites of Pan" Lew Tabackin -fl; Toshiko Akiyoshi -p; John Heard -b; Shelly Manne -d; recorded September 26 and 27, 1977 in Los Angeles 64263 BE-BOP 2.24 Inner City IC6052 64264 JITTERBUG WALTZ 6.39 --- 64265 RITES OF PAN 5.09 --- 64266 NIGHT NYMPH 2.17 --- 64267 ELUSIVE DREAM 4.05 --- Lew Tabackin -fl; Toshiko Akiyoshi -p; Bob Dougherty -b; Shelly Manne -d; recorded February 1978 in Los Angeles 64261 -

Headz, a Novel John Colagrande Jr

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 3-15-2007 Headz, a novel John Colagrande Jr. Florida International University DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI14060871 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Fiction Commons Recommended Citation Colagrande, John Jr., "Headz, a novel" (2007). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2401. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/2401 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida HEADZ, A NOVEL A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in CREATIVE WRITING by John Colagrande, Jr. 2007 To: Interim Dean Mark Szuchman College of Arts and Sciences This thesis, written by John Colagrande, Jr., and entitled Headz, a Novel, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved. Meri-Jane Rochelson James W. Hall John Dufresne, Major Professor Date of Defense: March 15, 2007 The thesis of John Colagrande, Jr. is approved. Interim Dean Mark Szuchman College of Arts and Sciences Dean George Walker University Graduate School Florida International University, 2007 DEDICATION To the family EPIGRAPH The Party, though its flame may flicker low and all but gutter in these juiceless times, goes on forever. -

The Lost Songs of Somerville

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2012 The Lost Songs of Somerville Scott Cerreta CUNY City College of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/510 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 The Lost Songs of Somerville By Scott Cerreta 2 I And a one, a two, a one, two, three, four. Remember me? I used to be the face of America, at least according to the painted cover of a once famous magazine. You’ll remember the picture if I show it to you: I’m the kid in the middle with the chipped tooth, a small flag planted in one young fist and a dying sparkler in the other; I’m sitting on a grassy hill with my family and some neighbors and the picture’s perspective is that of being just downhill looking up at us; our faces, still glowing with wonder, are all staring up into a darkening evening sky filled with fireworks which are, at that moment, in exact full neon blossom. Can’t find the likeness? Well, it was a long time ago and though some of us do, I guess most of us don’t, as children, much resemble our eventual adult selves. Anyway, the face of America wasn’t really me, it was our town, Somerville, they were referring to, back when this country was still knowable enough that one could imagine its true essence being found in such a small and simple space. -

Psaudio Copper

Issue 139 JUNE 21ST, 2021 Copper’s writers and I strive for excellence, and work hard to ensure that articles are carefully proofread. But errors occasionally slip by, and when they appear, they’re typically just flat-out brain freezes. For example, “passed” instead of “past,” “flare” rather than “flair” and “peel” in place of “peal.” (What is the correct spelling of “Aaagghhh?”) Responsibility for any such grammatical gaffes rests squarely on the shoulders of yours truly, although I do have the following excuses: by my rough estimate Copper publishes around 150 or more pages of ad-free content every month, and that’s a lotta words to look over; my in-house staff consists of me and Gary the pug; and I’ve had rotator cuff surgery. In the background, for the past year Rich Isaacs has been helping me catch and fix errors post- publication, and a third set of eyes – yours – may spot things we missed. If you see something, say something – we can fix flubs after they’re published. Now you see ‘em, now you don’t! In this issue: audio shows are returning, and B. Jan Montana reports on California’s T.H.E. Show. Before YouTube, how did people learn stuff? Why, with self-help records, as Rich Isaacs points out! J.I. Agnew continues his series, The Giants of Tape, with a look at the MCI JH-110. Russ Welton interviews the extraordinary acoustic guitarist Gordon Giltrap, and looks at the effects of standing waves in rooms. Wayne Robins reviews Soberish, Liz Phair’s new album, and her Horror Stories memoir. -

REPUBLICAN JOURNAL Sedation Is Advertised to Take at the Temple, Fire Insurance of of Brahma Hen in Town—24 in HO Dossli* FKOM ALL Ovelt the STATE

The Republican .Tottrnat, VOLUME 57. BELFAST, MAINE, THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 12, 1885. NUMBER 7. FARM. GARDEN progress; roads are better and sewing machines The Little Knight. Edna as he made me than Maine: Its Features and AND HOUSEHOLD. Carrington promise, Agricultural tion and preservation of fish and game, in open- the enclosed space is 25 feet square to the Notes by the Way. have been a Such a hen house as I was to become Edna Cranford.” lIKIM'lil.K'AN .Jol'RNAL. great help. The of olden Capabilities. ing navigable rivers to the passage of sea lish height of 150 feet when it is enlarged to 314 feet knight time, they say. “And he made this?” was A building this winter would have been a wonder you promise tlie through the building of and in a which is the size to the An iron TEN DAYS TRIP ON THE COAST. RAILROAD- For this Went bravely out to battle, fishways, gen- square, top. department brief suggestions, fuels, reply. “The selfish fellow! Hut Edna, what BY SAMUEL L. BOARDMAN. eral of our rivers ING. THE AT CUSHING. ROCK- by the 4*i years What would have serene conservancy and inland wat- stairway winds up on the inside to the 500 feet INQUEST iti isiu.i' r> nnRspw morning and are solicited ago. people thought And stood amid the strife. am 1 to experiences from housekeep- do without the little girl I have been ers. the over LAND. THE SIMONTON BROS.’ ESTABLISH- din roar During year 1882, 1.190,000 sal- landing, and consists of 900 steps. -

Discographie Leader/Co-Leader

Discographie Leader/Co-Leader 1947-1953 Urbanity Clef/Mercury NYC, September-October, 1947° & September 4, 1953¹. Tracks: Blues For Lady Day°; The Night We Called It A Day°; Yesterdays°; You're Blasé°; Tea For Two°; The Blue Room°; Thad's Pad¹; Things Are So Pretty In The Spring¹; Little Girl Blue¹; Odd Number¹. Personnel: Hank Jones: piano; Ray Brown¹: bass; Johnny Smith¹: guitar. Note: Reissued on Verve. 1955 The Trio Savoy NYC, August 4, 1955. Tracks: My Hearts Are Young; We Could Make Such Beautiful Music Together; We're All Together; Cyrano; Odd Number; There's A Small Hotel; My Funny Valentine; Now's The Time. Personnel: Hank Jones: piano; Wendell Marshall: bass; Kenny Clarke: drums. Note: Also issued as The Jazz Trio of Hank Jones. Quartet/Quintet Savoy NYC, November 1, 1955. Tracks: Almost Like Being In Love; An Evening At Papa Joe's; And Then Some; Summer's Gone; Don't Blame Me. Personnel: Donald Byrd: trumpet; Matty Dice: trumpet; Hank Jones: piano; Eddie Jones: bass; Kenny Clarke: drums. Bluebird Savoy NYC, November 1 & 3 & 29 & December 20, 1955. Tracks: Little Girl Blue; Bluebird; How High The Moon; Hank's Pranks; Alpha; Wine And Brandy. Personnel: Joe Wilder, Donald Byrd, Matty Dice: trumpet; Jerome Richardson: tenor sax, flute; Herbie Mann: flute; Hank Jones: piano; Wendell Marshall: bass; Eddie Jones: bass; Kenny Clarke: drums. 1956 Have You Met Hank Jones? Savoy NYC, July 9 & August 8 & 20, 1956. Tracks: Teddy's Dream; It Had To Be You; Gone With The Wind; Heart And Soul; But Not For Me; Have You Met Miss Jones?; You Don't Know What Love Is; How About You?; Body And Soul; Let's Fall In Love; Kanakee Shout; Solo Blues. -

Lew TABACKIN: Tatsuya TAKAHASHI

This discography is automatically generated by The JazzOmat Database System written by Thomas Wagner For private use only! ------------------------------------------ Lew TABACKIN: "Lew Tabackin" Lew Tabackin -ts,fl; Bob Dougherty -b; Bill Goodwin -d; recorded December 19, 1974 in Tokyo 11925 BYE BYE BLUES 7.22 RCA 6271 11926 SOLILOQUI 6.00 --- 21816 COME RAIN OR COME SHINE 7.36 --- 21817 MORNING 6.12 --- 21818 HOW DEEP IS THE OCEAN 5.52 --- 21821 LET THE TAPE ROLL 5.42 --- Lew Tabackin -ts; recorded December 19, 1974 in Tokyo 21822 GHOST OF A CHANCE 5.52 --- "Dual Nature" Lew Tabackin -fl,afl,ts[2]; Don Friedman -p; Bob Daugherty -b; Shelly Manne -d, perc; recorded August 31 and September 03, 1976 in Hollywood 69549 EUTERPE 7.15 Empathy EMP1001 69550 YELLOW IS MEOOW 5.48 --- 69551 OUT OF THIS WORLD 9.40 --- 69552 NO DUES BLUES (2) 9.22 --- 69553 MY IDEAL (2) 6.52 --- 69554 RUSSIAN LULLABY (2) 5.47 --- "Trackin'" Lew Tabackin -ts,fl; Toshiko Akiyoshi -p; Bob Daugherty -b; Shelly Manne -d; recorded September 03, 1976 in Hollywood 17075 I'M ALL SMILES 6.35 RCA RDC-3 17076 COTTON TAIL 5.49 --- 17077 TRACKIN' 6.16 --- 17078 SUMMERTIME 4.42 --- "Rites of Pan" Lew Tabackin -fl; Toshiko Akiyoshi -p; John Heard -b; Shelly Manne -d; recorded September 26 and 27, 1977 in Los Angeles 64263 BE-BOP 2.24 Inner City IC6052 64264 JITTERBUG WALTZ 6.39 --- 64265 RITES OF PAN 5.09 --- 64266 NIGHT NYMPH 2.17 --- 64267 ELUSIVE DREAM 4.05 --- Lew Tabackin -fl; Toshiko Akiyoshi -p; Bob Dougherty -b; Shelly Manne -d; recorded February 1978 in Los Angeles 64261