The Lost Songs of Somerville

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IS/SONY in High Gear W/Japanese Market on Eve Ur Inch Disks Bow

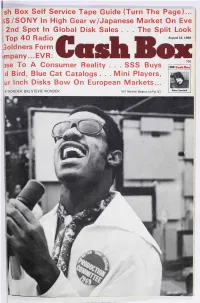

i sh Box Self Service Tape Guide (Turn The Page) ... IS/SONY In High Gear w/Japanese Market On Eve 2nd Spot In Global Disk Sales . The Split Look August 16, 1969 i Top 40 Radio ,;oldners Form ash.,mpany...EVR: )se To A Consumer Reality ... SSS Buys Ott Cash Box754 d Bird, Blue Cat Catalogs ... Mini Players, ur Inch Disks Bow On European Markets... Peter Sarstedt E WONDER: BIG STEVIE WONDER Intl Section Begins on Pg. 61 www.americanradiohistory.com The inevitable single from the group that brought you "Young Girl" and "WomanYVoman:' EC "This Girl Is Dir Ai STA BII aWoman Now7 hbAn. by Gary Puckett COiN and The Union Gap. DEE On Columbia Records* Di 3 II Lodz,' Tel: 11A fie 1%. i avb .» o www.americanradiohistory.com ///1\\ %b\\ ISM///1\\\ ///=1\\\ Min 111 111\ //Il11f\\ 11111111111111 1/11111 III111 MUSIC -RECORD WEEKLY ii INTERNATIONAL milli 1IUUIII MI/I/ MIII II MU/// MUMi M1111/// U1111D U IULI glia \\\1197 VOL. XXXI - Number 3/August 16, 1969 Publication Office / 1780 Broadway, New York, New York 10019 / Telephone JUdson 6-2640 / Cable Address: Cash Box, N. Y. GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher MARTY OSTROW Vice President IRV LICHTMAN Editor in Chief EDITORIAL MARV GOODMAN Cash Box Assoc. Editor JOHN KLEIN BOB COHEN BRUCE HARRIS Self- Service EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS MIKE MARTUCCI ANTHONY LANZETTA Tape Guide ADVERTISING BERNIE BLAKE Director of Advertising ACCOUNT EXECUTIVES STAN SOIFER, New York BILL STUPER, New York HARVEY GELLER, Hollywood Much of the confusion facing first - 8 -TRACK CARTRIDGES: Using the WOODY HARDING unit tape consumers lies in the area same speed and thickness of tape Art Director of purchaser education. -

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

DEPICTIONS of CHASTITY: VIRTUE MADE VISIBLE Susan L'engle In

DEPICTIONS OF CHASTITY: VIRTUE MADE VISIBLE Susan L’Engle In 1969 a daughter was born to Cher and Sonny Bono. They named her Chastity, an uncommon and burdensome name for a child to bear in this time and place. The negative resonance of this name still prevails, clearly articulated in a 1996 interview with Chastity Bono, where the reporter commented: “When she was born in 1969, Chastity Bono got stuck with that name forever. ‘Not that many people call me Chastity anyway,’ she says. She prefers Chas. Hell, wouldn’t you?”1 Today in the twenty-fi rst century we all have personal takes on the meaning of the word chastity and its relevance to our individual lives, shaped by our upbringing and education and supplemented by input from various media. In the Middle Ages, however, chastity was an all- pervading and multivalent concept that regulated the lives of lay men and women, and clergy alike. The ideals of chastity were expressed verbally by churchmen, theologians, philosophers, poets, and heads of family—and recorded in sermons, Saints’ Lives, advice manuals for rulers, courtesy books, and poems of courtly romance. For many of these texts, artists created images and compositions to illustrate and reinforce the verbal discourse, and it is these visual manifestations that will be analyzed and discussed in this project. As a medievalist I am interested in the various ramifi cations of chas- tity within the strata of medieval society; as an art historian, I want to explore how the notion of chastity can be represented visually, and what circumstances provoke its illustration. -

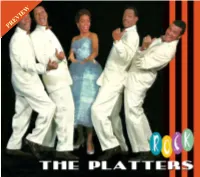

PREVIEW PREVIEW Previewstrictly on the Surface, ‘The Platters Rock’ Just Doesn’T Sound Right

PREVIEW PREVIEW PREVIEWStrictly on the surface, ‘The Platters Rock’ just doesn’t sound right. During the mid-to-late 1950s, the ultra- polished vocal group was the epitome of cool, velvet-smooth harmonizing as they cranked out an avalanche of smash ballads under the supervision of manager Buck Ram. Filmmakers cast them as the relatively safe and sedate antidote to the otherwise steamy sounds dished up in the memorable films ‘Rock Around the Clock,’ ‘The Girl Can’t Help It,’ ‘Rock All Night,’ ‘Carnival Rock,’ and ‘Girls Town,’ their segments allowing overheated teenagers a chance to to. They’d started out as an R&B vocal group cool down a bit in their sweaty theater seats. before magnificently crossing over to the pop realm, and that early training never deserted Yet a close examination of their mammoth them altogether. catalog for Chicago’s Mercury Records reveals a surprising number of up-tempo The quintet’s unusual four-guys-and-one- gems that entirely legitimize the concept of gal lineup was influential in itself, mirrored this collection. You may not recognize all by a number of African American vocal of the titles at first glance, but taken as a groups that followed in their wake (most whole they confirm that The Platters could notably Smokey Robinson’s Miracles). But indeed rock whenever Ram allowed them very few outfits could boast the presence of 5 a stratospheric lead tenor the equal of The Bass singer Herb Reed was the first Platters’ Tony Williams, whose powerful, member that we now revere as a Platter to PREVIEWgymnastic vocal flights approximated a ride come into the fold. -

2020 May June Newsletter

MAY / JUNE NEWSLETTER CLUB COMMITTEE 2020 CONTENT President Karl Herman 2304946 President Report - 1 Secretary Clare Atkinson 2159441 Photos - 2 Treasurer Nicola Fleming 2304604 Club Notices - 3 Tuitions Cheryl Cross 0275120144 Jokes - 3-4 Pub Relations Wendy Butler 0273797227 Fundraising - 4 Hall Mgr James Phillipson 021929916 Demos - 5 Editor/Cleaner Jeanette Hope - Johnstone Birthdays - 5 0276233253 New Members - 5 Demo Co-Ord Izaak Sanders 0278943522 Member Profile - 6 Committee: Pauline Rodan, Brent Shirley & Evelyn Sooalo Rock n Roll Personalities History - 7-14 Sale and wanted - 15 THE PRESIDENTS BOOGIE WOOGIE Hi guys, it seems forever that I have seen you all in one way or another, 70 days to be exact!! Bit scary and I would say a number of you may have to go through beginner lessons again and also wear name tags lol. On the 9th of May the national association had their AGM with a number of clubs from throughout New Zealand that were involved. First time ever we had to run the meeting through zoom so talking to 40 odd people from around the country was quite weird but it worked. A number of remits were discussed and voted on with a collection of changes mostly good but a few I didn’t agree with but you all can see it all on the association website if you are interested in looking . Also senior and junior nationals were voted on where they should be hosted and that is also advertised on their website. Juniors next year will be in Porirua and Seniors will be in Wanganui. -

Q Casino Announces Four Shows from This Summer's Back Waters

Contact: Abby Ferguson | Marketing Manager 563-585-3002 | [email protected] February 28, 2018 - For Immediate Release Q Casino Announces Four Shows From This Summer’s Back Waters Stage Concert Lineup! Dubuque, IA - The Back Waters Stage, Presented by American Trust, returns this summer on Schmitt Island! Q Casino is proud to announce the return of our outdoor summer experience, Back Waters Stage. This summer, both national acts and local favorites will take the stage through community events and Q Casino hosted concerts. All ages are welcome to experience the excitement at this outdoor venue. Community members can expect to enjoy a wide range of concerts from all genres from modern country to rock. The Back Waters Stage will be sponsoring two great community festivals this summer. Kickoff to Summer will be kicking off the summer series with a free show on Friday, May 25. Summer’s Last Blast 19 which is celebrating 19 years of raising money for area charities including FFA, the Boy Scouts, Dubuque County Fairgrounds and Sertoma. Summer’s Last Blast features the area’s best entertainment with free admission on Friday, August 24 and Saturday, August 25. The Back Waters Stage Summer Concert Series starts off with country rappers Colt Ford and Moonshine Bandits on Saturday, June 16. Colt Ford made an appearance in the Q Showroom last March to a sold out crowd. Ford has charted six times on the Hot Country Songs charts and co-wrote “Dirt Road Anthem,” a song later covered by Jason Aldean. On Thursday, August 9, the Back Waters Stage switches gears to modern rock with platinum recording artist, Seether. -

Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt487035r5 No online items Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Michael P. Palmer Processing partially funded by generous grants from Jim Deeton and David Hensley. ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives 909 West Adams Boulevard Los Angeles, California 90007 Phone: (213) 741-0094 Fax: (213) 741-0220 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.onearchives.org © 2009 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Coll2007-020 1 Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Collection number: Coll2007-020 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives Los Angeles, California Processed by: Michael P. Palmer, Jim Deeton, and David Hensley Date Completed: September 30, 2009 Encoded by: Michael P. Palmer Processing partially funded by generous grants from Jim Deeton and David Hensley. © 2009 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Ralph W. Judd collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Dates: 1848-circa 2000 Collection number: Coll2007-020 Creator: Judd, Ralph W., 1930-2007 Collection Size: 11 archive cartons + 2 archive half-cartons + 1 records box + 8 oversize boxes + 19 clamshell albums + 14 albums.(20 linear feet). Repository: ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. Los Angeles, California 90007 Abstract: Materials collected by Ralph Judd relating to the history of cross-dressing in the performing arts. The collection is focused on popular music and vaudeville from the 1890s through the 1930s, and on film and television: it contains few materials on musical theater, non-musical theater, ballet, opera, or contemporary popular music. -

![[E:] 09 a Second Face.Mp3=2129222 ACDC Whole Lotta Rosie (Rare Live](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7220/e-09-a-second-face-mp3-2129222-acdc-whole-lotta-rosie-rare-live-217220.webp)

[E:] 09 a Second Face.Mp3=2129222 ACDC Whole Lotta Rosie (Rare Live

mTad [E:] 09 A Second face.mp3=2129222 ACDC Whole Lotta Rosie (rare live Bon Scott).mp3=4874280 Damnation of Adam Blessing - Second Damnation - 05 - Back to the River.mp3=5113856 Eddie Van Halen - Eruption (live, rare).mp3=2748544 metallica - CreepingDeath (live).mp3=4129152 [E:\1959 - Miles Davis - Kind Of Blue] 01 So What.mp3=13560814 02 Freddie Freeloader.mp3=14138851 03 Blue In Green.mp3=8102685 04 All Blues.mp3=16674264 05 Flamenco Sketches.mp3=13561792 06 Flamenco Sketches (Alternate Take).mp3=13707024 B000002ADT.01.LZZZZZZZ.jpg=19294 Thumbs.db=5632 [E:\1965 - The Yardbirds & Sonny Boy Williamson] 01 - Bye Bye Bird.mp3=2689034 02 - Mister Downchild.mp3=4091914 03 - 23 Hours Too Long.mp3=5113866 04 - Out Of The Water Coast.mp3=3123210 05 - Baby Don't Worry.mp3=4472842 06 - Pontiac Blues.mp3=3864586 07 - Take It Easy Baby (Ver 1).mp3=4153354 08 - I Don't Care No More.mp3=3166218 09 - Do The Weston.mp3=4065290 10 - The River Rhine.mp3=5095434 11 - A Lost Care.mp3=2060298 12 - Western Arizona.mp3=2924554 13 - Take It Easy Baby (Ver 2).mp3=5455882 14 - Slow Walk.mp3=1058826 15 - Highway 69.mp3=3102730 albumart_large.jpg=11186 [E:\1971 Nazareth] 01 - Witchdoctor Woman.mp3=3994574 02 - Dear John.mp3=3659789 03 - Empty Arms, Empty Heart.mp3=3137758 04 - I Had A Dream.mp3=3255194 05 - Red Light Lady.mp3=5769636 06 - Fat Man.mp3=3292392 07 - Country Girl.mp3=3933959 08 - Morning Dew.mp3=6829163 09 - The King Is Dead.mp3=4603112 10 - Friends (B-side).mp3=3289466 11 - Spinning Top (alternate edit).mp3=2700144 12 - Dear John (alternate edit).mp3=2628673 -

FRED NEIL LYRICS Compiled by Robin Dunn & Chrissie Van Varik

FRED NEIL LYRICS Compiled by Robin Dunn & Chrissie van Varik. Fred Neil (16 th March 1936 –7th July 2001) was one of the most compelling folk singer-songwriters in the 1960s and early 1970s. His marvellously deep, rich and impossibly low baritone enchanted everyone who has ever heard a Fred Neil song - and continues to do so. Surely one of the most beautiful voices in music. Bob Dylan said, “Fred had a strong, powerful voice, almost a bass voice, and a powerful sense of rhythm. He used to play mostly the type of songs that Josh White might sing. I used to sing and play harmonica for him, and then once in a while get to sing a song.” Yet as performer success eluded Fred, mainly because it was the last thing he pursued. A reluctance to tour didn’t help much either (a trait he shared with Bobby Charles and Harry Nilsson). According to his producer, Nik Venet, Fred was “probably the most famous and financially successful ‘cult artist’ in the history of the world...and could have been even bigger if he’d wanted to be....but he just didn’t!” Fred Neil showed up unexpectedly and was gone before you knew it. A loner and somewhat of a recluse, he was exceedingly hard to get to know and thus remained an enigma to most. John Sebastian, who played on his two Elektra albums, describes his background as “sketchy”. He is best known to the world through other people’s recordings of his material, such as ‘Everybody’s Talkin’’, made famous by Harry Nilsson as the theme to the movie Midnight Cowboy (and earned a Grammy) and ‘Other Side of This Life’, recorded by several but most notably by Jefferson Airplane. -

Jerry Garcia Song Book – Ver

JERRY GARCIA SONG BOOK – VER. 9 1. After Midnight 46. Chimes of Freedom 92. Freight Train 137. It Must Have Been The 2. Aiko-Aiko 47. blank page 93. Friend of the Devil Roses 3. Alabama Getaway 48. China Cat Sunflower 94. Georgia on My Mind 138. It Takes a lot to Laugh, It 4. All Along the 49. I Know You Rider 95. Get Back Takes a Train to Cry Watchtower 50. China Doll 96. Get Out of My Life 139. It's a Long, Long Way to 5. Alligator 51. Cold Rain and Snow 97. Gimme Some Lovin' the Top of the World 6. Althea 52. Comes A Time 98. Gloria 140. It's All Over Now 7. Amazing Grace 53. Corina 99. Goin' Down the Road 141. It's All Over Now Baby 8. And It Stoned Me 54. Cosmic Charlie Feelin' Bad Blue 9. Arkansas Traveler 55. Crazy Fingers 100. Golden Road 142. It's No Use 10. Around and Around 56. Crazy Love 101. Gomorrah 143. It's Too Late 11. Attics of My Life 57. Cumberland Blues 102. Gone Home 144. I've Been All Around This 12. Baba O’Riley --> 58. Dancing in the Streets 103. Good Lovin' World Tomorrow Never Knows 59. Dark Hollow 104. Good Morning Little 145. Jack-A-Roe 13. Ballad of a Thin Man 60. Dark Star Schoolgirl 146. Jack Straw 14. Beat it on Down The Line 61. Dawg’s Waltz 105. Good Time Blues 147. Jenny Jenkins 15. Believe It Or Not 62. Day Job 106. -

A Stylistic Analysis of 2Pac Shakur's Rap Lyrics: in the Perpspective of Paul Grice's Theory of Implicature

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2002 A stylistic analysis of 2pac Shakur's rap lyrics: In the perpspective of Paul Grice's theory of implicature Christopher Darnell Campbell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Campbell, Christopher Darnell, "A stylistic analysis of 2pac Shakur's rap lyrics: In the perpspective of Paul Grice's theory of implicature" (2002). Theses Digitization Project. 2130. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2130 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF 2PAC SHAKUR'S RAP LYRICS: IN THE PERSPECTIVE OF PAUL GRICE'S THEORY OF IMPLICATURE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English: English Composition by Christopher Darnell Campbell September 2002 A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF 2PAC SHAKUR'S RAP LYRICS: IN THE PERSPECTIVE OF PAUL GRICE'S THEORY OF IMPLICATURE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Christopher Darnell Campbell September 2002 Approved.by: 7=12 Date Bruce Golden, English ABSTRACT 2pac Shakur (a.k.a Makaveli) was a prolific rapper, poet, revolutionary, and thug. His lyrics were bold, unconventional, truthful, controversial, metaphorical and vulgar. -

Best Defence Sectors

Fraud Advisory Panel Ninth Annual Review 2006-2007 Ethical is bestthe defencebehaviour againstfraud It’s all about choices LOW RES PROOF ONLY Ethical behaviour is rooted in individual choices but that’s not the whole story. Government, business and media supply inspirations and incentives that help set the tone of our society. Some of these are making an inadvertent but powerful contribution to the growth of fraud. LOW RES PROOF ONLY Contents The Fraud Advisory Panel is an independent body 2 Chairman’s Overview: with members from both the public and private The Best Defence sectors. Its role is to raise awareness of the immense human, social and economic damage caused by fraud 3 About The Panel and to develop effective remedies. 3 Programme 3 Joining The Panel works to: 3 Corporate Members 4 Trustees • originate proposals to reform the law and public policy, with a particular focus on fraud 6 Public Policy: investigations and prosecutions. “A Once in a Generation Chance” • Advise business and the public on prevention, 6 At least £20 Billion a Year 6 Aspirations and Realities detection and reporting. 7 Six Cheap and Simple Steps • Assist in improving education and training in business and the professions. 8 Ethics and Fraud • Establish a more accurate picture of the extent, 9 The Social Context causes and nature of fraud. 9 Inspirations and Incentives 9 A Zone of Tolerance The Panel has a truly multi-disciplinary perspective. 10 Marginalising Ethical Criteria No other organisation has such a range and depth 10 Getting Away With It of knowledge, both of the problem and of ways to 11 The Business Context combat it.