Headz, a Novel John Colagrande Jr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Aster Marketing Thesi

ERASMUS SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS ECONOMICS - MARKETING MASTER THESIS It's All in the Lyrics: The Predictive Power of Lyrics Date : August, 2014 Name : Maarten de Vos Student ID : 331082 Supervisor : Dr. F. Deutzmann Abstract: This research focuses on whether it is possible to determine popularity of a specific song based on its lyrics. The songs which were considered were in the US Billboard Top 40 Singles Chart between 2006 and 2011. From this point forward, k-means clustering in RapidMiner has been used to determine the content that was present in the songs. Furthermore, data from Last.FM was used to determine the popularity of a song. This resulted in the conclusion that up to a certain extent, it is possible to determine popularity of songs. This is mostly applicable to the love theme, but only in the specific niches of it. Keywords: Content analysis, RapidMiner, Lyric analysis, Last.FM, K-means clustering, US Billboard Top 40 Singles Chart, Popularity 1 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Motivation ........................................................................................................................................ 5 2.1. Academic contribution .............................................................................................................. 5 2.2. Managerial contribution .......................................................................................................... -

Seacare Authority Exemption

EXEMPTION 1—SCHEDULE 1 Official IMO Year of Ship Name Length Type Number Number Completion 1 GIANT LEAP 861091 13.30 2013 Yacht 1209 856291 35.11 1996 Barge 2 DREAM 860926 11.97 2007 Catamaran 2 ITCHY FEET 862427 12.58 2019 Catamaran 2 LITTLE MISSES 862893 11.55 2000 857725 30.75 1988 Passenger vessel 2001 852712 8702783 30.45 1986 Ferry 2ABREAST 859329 10.00 1990 Catamaran Pleasure Yacht 2GETHER II 859399 13.10 2008 Catamaran Pleasure Yacht 2-KAN 853537 16.10 1989 Launch 2ND HOME 856480 10.90 1996 Launch 2XS 859949 14.25 2002 Catamaran 34 SOUTH 857212 24.33 2002 Fishing 35 TONNER 861075 9714135 32.50 2014 Barge 38 SOUTH 861432 11.55 1999 Catamaran 55 NORD 860974 14.24 1990 Pleasure craft 79 199188 9.54 1935 Yacht 82 YACHT 860131 26.00 2004 Motor Yacht 83 862656 52.50 1999 Work Boat 84 862655 52.50 2000 Work Boat A BIT OF ATTITUDE 859982 16.20 2010 Yacht A COCONUT 862582 13.10 1988 Yacht A L ROBB 859526 23.95 2010 Ferry A MORNING SONG 862292 13.09 2003 Pleasure craft A P RECOVERY 857439 51.50 1977 Crane/derrick barge A QUOLL 856542 11.00 1998 Yacht A ROOM WITH A VIEW 855032 16.02 1994 Pleasure A SOJOURN 861968 15.32 2008 Pleasure craft A VOS SANTE 858856 13.00 2003 Catamaran Pleasure Yacht A Y BALAMARA 343939 9.91 1969 Yacht A.L.S.T. JAMAEKA PEARL 854831 15.24 1972 Yacht A.M.S. 1808 862294 54.86 2018 Barge A.M.S. -

Lisa DEL SOL Columbia University

7 Race Relations and Conversations as Hip-Hop Calls Out Anime In TweRk by Latasha N. Nevada Diggs Lisa DEL SOL Columbia University The poetry of Latasha N. Nevada Diggs (2013) moves beyond the conventional boundaries separating music and text within traditional Western literature in her book TweRk. By both actively connecting and fusing music and text into this body of work she creates a text with a sonic element that moves beyond the boundaries of the page. Diggs (2013) further complicates the relationship between text, sound and visual media in her poetry which is a fusion of pop culture, rhythm, African American Vernacular English (AAVE) and a multitude of languages (including various Caribbean Patois) making it difficult to categorize her poetry due to its polyphonic nature. Diggs’s (2013) poetry ranges from references and direct quotes from hip-hop songs (such as titles and lyrics), as well as alluding to particular rhythms all while addressing stereotypes of sexism and combatting worldwide images of anti-blackness. I will discuss sound and its relationship to poetry, the role of pop culture in the text, and its interactions with misogynoir.1 Using Edouard Glissant’s terminology for language and culture in the Caribbean being an amalgamation of sorts, what he called Antillanité2 and viewing Diggs’s (2013) representation of Blackness through a multicultural lens disrupts the monolithic narrative of Black identity. She invokes a pluralistic perspective on language with her use of Japanese, English and AAVE in the same poem. She also examines the duality of Black identity, what WEB DuBois referred to as double consciousness (DuBois 1961, 3) and alienation exemplifying the “twoness” the “two souls, two thoughts and two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body” (DuBois 1961, 3). -

ATHABASCA UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY of CALGARY UNIVERSITY of LETHBRIDGE SONGWRITING in THERAPY by JOHN A. DOWNES a Final Project

ATHABASCA UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY UNIVERSITY OF LETHBRIDGE SONGWRITING IN THERAPY BY JOHN A. DOWNES A Final Project submitted to the Campus Alberta Applied Psychology: Counselling Initiative In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF COUNSELLING Alberta August 2006 i ii iii Abstract Songwriting addresses therapy on multiple levels: through the process, product, and experience of songwriting in the context of a therapeutic relationship. A literature review provides the background and rationale for writing a guide to songwriting in therapy. The resource guide illustrates 18 techniques of songwriting in therapy. Each technique includes details regarding salient features, clinical uses, client prerequisites, therapist skills, goals, media and roles, format, preparation required, procedures, data interpretation, and client/group-therapist dynamics. An ethical dilemma illustrates the need for caution when implementing songwriting in therapy. Examples of consent forms are included in the guide. The author concludes by reviewing what he has learned in the process of researching and writing the guide, and evaluates his research. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I – Songwriting in Therapy………………………………………….………..1 Rationale………………………………………………………………………….……...1 Identifying the Need…………………………………………………………….1 Creating a resource……………………………………………………..………2 Data analysis…………………………………………………………….………2 An ethical question…………………………………………………….………..3 Implications………………………………………………………………………3 Chapter II –Songwriting: A Useful Therapeutic -

Five Star Transcript

Five Star Transcript Timecode Character Dialogue/Description Explanation INT: Car, Night 01:00:30:00 Primo March 24th, 2008, a little boy was born. 01:00:40:00 Sincere Israel Najir Grant, my son. 01:01:00:00 That's my son. 01:01:01:00 You know where I was? Nah, not the hospital bed. 01:01:10:00 Nah not in the waiting room. 01:01:13:00 I was locked the fuck up. 01:01:23:00 Remember gettin' that call, putting the call in I should say. Had a beautiful baby boy, and I wasn't there to greet him when he 01:01:33:00 came into the world. 01:01:36:00 And, um, it's funny. 01:01:40:00 I was released the week after. 01:01:43:00 April 1st, my Pop's birthday. Dialogue Transcript Five Star a film by Keith Miller 1 Five Star Transcript Timecode Character Dialogue/Description Explanation 01:01:48:00 Came home on April Fool's Day, dig that. I remember walking in, into the P's*. Everybody yo Primo, Primo oh, 01:01:56:00 * P’s = projects/housing project shit. 01:02:03:00 Fuck y'all. I want to see my son. 01:02:06:00 Walked up the stairs, I was nervous. 01:02:14:00 Haven't seen my daughter in so long. Open the door, everybody greeting me. Oh welcome home! Welcome 01:02:20:00 home! Yeah it's nice, that that that was sweet. Move! I want to see my son. -

Flashback, Flash Forward: Re-Covering the Body and Id-Endtity in the Hip-Hop Experience

FLASHBACK, FLASH FORWARD: RE-COVERING THE BODY AND ID-ENDTITY IN THE HIP-HOP EXPERIENCE Submitted By Danicia R. Williams As part of a Tutorial in Cultural Studies and Communications May 04,2004 Chatham College Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Tutor: Dr. Prajna Parasher Reader: Ms. Sandy Sterner Reader: Dr. Robert Cooley ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Prajna Paramita Parasher, my tutor for her faith, patience and encouragement. Thank you for your friendship. Ms. Sandy Sterner for keeping me on my toes with her wit and humor, and Dr. Cooley for agreeing to serve on my board. Kathy Perrone for encouraging me always, seeing things in me I can only hope to fulfill and helping me to develop my writing. Dr. Anissa Wardi, you and Prajna have changed my life every time I attend your classes. My parent s for giving me life and being so encouraging and trusting in me even though they weren't sure what I was up to. My Godparents, Jerry and Sharon for assisting in the opportunity for me to come to Chatham. All of the tutorial students that came before me and all that will follow. I would like to give thanks for Hip-Hop and Sean Carter/Jay-Z, especially for The Black Album. With each revolution of the CD my motivation to complete this project was renewed. Whitney Brady, for your excitement and brainstorming sessions with me. Peace to Divine Culture for his electricity and Nabri Savior. Thank you both for always being around to talk about and live in Hip-Hop. Thanks to my friends, roommates and coworkers that were generally supportive. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

ORC Special Regulations Mo3 with Life Raft

ISAF OFFSHORE SPECIAL REGULATIONS Including US Sailing Prescriptions www.ussailing.org Extract for Race Category 1 Multihulls JANUARY 2014 - DECEMBER 2015 © ORC Ltd. 2002, all amendments from 2003 © International Sailing Federation, (IOM) Ltd. Version 1-3 2014 Because this is an extract not all paragraph numbers will be present RED TYPE/SIDE BAR indicates a significant change in 2014 US Sailing extract files are available for individual categories and boat types (monohulls and multihulls) at: http://www.ussailing.org/racing/offshore-big-boats/big-boat-safety-at-sea/special- regulations/extracts US Sailing prescriptions are printed in bold, italic letters Guidance notes and recommendations are in italics The use of the masculine gender shall be taken to mean either gender SECTION 1 - FUNDAMENTAL AND DEFINITIONS 1.01 Purpose and Use 1.01.1 It is the purpose of these Special Regulations to establish uniform ** minimum equipment, accommodation and training standards for monohull and multihull yachts racing offshore. A Proa is excluded from these regulations. 1.01.2 These Special Regulations do not replace, but rather supplement, the ** requirements of governmental authority, the Racing Rules and the rules of Class Associations and Rating Systems. The attention of persons in charge is called to restrictions in the Rules on the location and movement of equipment. 1.01.3 These Special Regulations, adopted internationally, are strongly ** recommended for use by all organizers of offshore races. Race Committees may select the category deemed most suitable for the type of race to be sailed. 1.02 Responsibility of Person in Charge 1.02.1 The safety of a yacht and her crew is the sole and inescapable ** responsibility of the person in charge who must do his best to ensure that the yacht is fully found, thoroughly seaworthy and manned by an experienced crew who have undergone appropriate training and are physically fit to face bad weather. -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

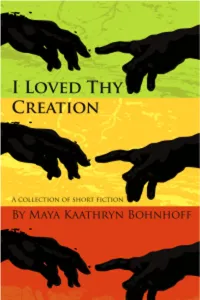

I Loved Thy Creation

I Loved Thy Creation A collection of short fiction by Maya Kaathryn Bohnhoff O SON OF MAN! I loved thy creation, hence I created thee. Bahá’u’lláh Copyright 2008, Maya Kaathryn Bohnhoff and Juxta Publishing Limited. www.juxta.com. Cover image "© Horvath Zoltan | Dreamstime.com" ISBN 978-988-97451-8-9 This book has been produced with the consent of the original authors or rights holders. Authors or rights holders retain full rights to their works. Requests to reproduce the contents of this work can be directed to the individual authors or rights holders directly or to Juxta Publishing Limited. Reproduction of this book in its current form is governed by the Juxta Publishing Books for the World license outlined below. This book is released as part of Juxta Publishing's Books for the World program which aims to provide the widest possible access to quality Bahá'í-inspired literature to readers around the world. Use of this book is governed by the Juxta Publishing Books for the World license: 1. This book is available in printed and electronic forms. 2. This book may be freely redistributed in electronic form so long as the following conditions are met: a. The contents of the file are not altered b. This copyright notice remains intact c. No charges are made or monies collected for redistribution 3 The electronic version may be printed or the printed version may be photocopied, and the resulting copies used in non-bound format for non-commercial use for the following purposes: a. Personal use b. Academic or educational use When reproduced in this way in printed form for academic or educational use, charges may be made to recover actual reproduction and distribution costs but no additional monies may be collected. -

20 Second Songs to Sing While Washing Your Hands

20 SECOND SONGS TO SING WHILE WASHING YOUR HANDS “Billie Jean” “Love on Top” by Michael Jackson by Beyonce Billie Jean is not my lover Baby it’s you She’s just a girl who claims that, I am the one You’re the one I love But the kid is not my son You’re the one I need She says I am the one, but the kid is not my son You’re the only one I see Come on baby it’s you “No Scrubs” You’re the one that gives your all by TLC You’re the one I can always call When I need to make everything stop No, I don’t want no scrubs Finally you put my love on top A scrub is a guy that can’t get no love from me Hangin’ out the passenger side of his best friend’s ride “Beat It” Trying to holla at me by Michael Jackson I don’t want no scrubs Just beat it, beat it, beat it, beat it A scrub is a guy that can’t get no love from me No one wants to be defeated Hangin’ out that passenger side of his best Showin’ how funky and strong is your fight friend’s ride It doesn’t matter who’s wrong or right Trying to holla at me Just beat it (beat it) Just beat it (beat it) “Jolene” Just beat it (beat it) by Dolly Parton Just beat it (beat it, uh) Jolene, Jolene, Jolene, Jolene I’m begging of you please don’t take my man “Gangsta’s Paradise” Jolene, Jolene, Jolene, Jolene by Coolio Please don’t take him just because you can As I walk through the valley of the shadow of death “Africa” I take a look at my life and realize there’s by Toto nothin’ left It’s gonna take a lot to drag me away from you Cause I’ve been blastin’ and laughin’ so long There’s nothing that a hundred men or more that even my mama thinks that my mind is gone could ever do But I ain’t never crossed a man that I bless the rains down in Africa didn’t deserve it Gonna take some time to do the things Me be treated like a punk, you know we never had that’s unheard of You better watch how you’re talkin’ and “Over the Rainbow” where you’re walkin by Judy Garland Somewhere over the rainbow Way up high And the dreams that you dream of Once in a Lullaby.