Roots for Good Governance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grouped by Cluster

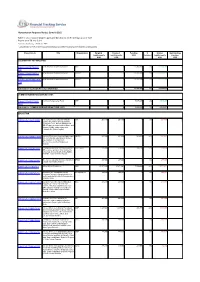

Humanitarian Response Plan(s): Somalia 2015 Table E: List of appeal projects (grouped by Cluster), with funding status of each Report as of 28-Sep-2021 http://fts.unocha.org (Table ref: R##) Compiled by OCHA on the basis of information provided by donors and recipient organizations. Project Code Title Organization Original Revised Funding % Unmet Outstanding requirements requirements USD Covered requirements pledges USD USD USD USD CLUSTER NOT YET SPECIFIED SOM-15/SNYS/78452/ to be allocated to specific projects WFP 0 0 15,200,048 0% -15,200,048 0 561 SOM-15/SNYS/78471/ to be allocated to specific projects UNHCR 0 0 22,776,204 0% -22,776,204 0 120 SOM-15/SNYS/78658/R/ to be allocated to specific projects UNICEF 0 0 13,712,399 0% -13,712,399 0 124 Sub total for CLUSTER NOT YET SPECIFIED 0 0 51,688,651 0% -51,688,651 0 COMMON HUMANITARIAN FUND (CHF) SOM-15/SNYS/77965/ Common Humanitarian Fund CHF 0 0 9,595,257 0% -9,595,257 0 7622 Sub total for COMMON HUMANITARIAN FUND (CHF) 0 0 9,595,257 0% -9,595,257 0 EDUCATION SOM-15/E/71574/8380 Increasing Access & Quality of Basic JCC 201,150 201,150 0 0% 201,150 0 Literacy for Children and Adults from Vulnerable, Poor, Women Headed and IDP / Returness Households in Bu'ale and Salagle (Middle Jubba region) and Celbarde-Ato (Bakool region) SOM-15/E/71608/14579 Improved Protective Learning Spaces and FENPS 451,400 451,400 289,999 64% 161,401 0 Access to Quality Education for School Age Children in Humanitarian Emergencies and Conflict Areas in Somalia SOM-15/E/71628/5660 Emergency education for crises-affected -

1 a Cultural Heritage for National Liberation?

A Cultural Heritage for National Liberation? The Soviet-Somali Historical Expedition, So- viet African Studies, and the Cold War in the Horn of Africa Natalia Telepneva British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow, University of Warwick This paper discusses the conception, execution, and outcomes of the first Soviet-Somali histor- ical expedition, in 1971. In due course, the Soviet-Somali Expedition set out to create a “usable past” for Somali nationalism, rooted in the history of Mohammad Abdullah Hassan, a religious and military leader who had fought against the British in Somaliland between 1900 and 1920. The paper investigates how Soviet ideas about the preservation of historical heritage were grounded in Central Asian modes of practice and how these became internalised by Soviet Africanists in their attempts to help reinforce foundational myths in newly independent African states. The paper argues that the Soviet model for the preservation of cultural heritage, as envisioned by Soviet Africanists, aimed to reinforce Siad’s national project for Somalia. Their efforts were ultimately unsuccessful, however, because of Cold War constraints and misunder- standings of local realities. Keywords: Soviet Union, Africa, Somalia, Cold War, Somali cultural heritage, UNESCO Introduction On 10 September 1971, Siad Barre, the head of the Somali Revolutionary Council (SRC), spoke to a group of Soviet scholars that had arrived to participate in the first joint Soviet-Somali historico-archeological expedition. “Imperialists always wrote lies about us. They collected such ma- terials that had no value; made photographs of those objects which showed us in the wrong light. Your expedition and research should be cardinally different from what has been written by bourgeois authors. -

Assessment Report 2011

ASSESSMENT REPORT 2011 PHASE 1 - PEACE AND RECONCILIATION JOIN- TOGETHER ACTION For Galmudug, Himan and Heb, Galgaduud and Hiiraan Regions, Somalia Yme/NorSom/GSA By OMAR SALAD BSc (HONS.) DIPSOCPOL, DIPGOV&POL Consultant, in collaboration with HØLJE HAUGSJÅ (program Manager Yme) and MOHAMED ELMI SABRIE JAMALLE (Director NorSom). 1 Table of Contents Pages Summary of Findings, Analysis and Assessment 5-11 1. Introduction 5 2. Common Geography and History Background of the Central Regions 5 3. Political, Administrative Governing Structures and Roles of Central Regions 6 4. Urban Society and Clan Dynamics 6 5. Impact of Piracy on the Economic, Social and Security Issues 6 6. Identification of Possibility of Peace Seeking Stakeholders in Central Regions 7 7. Identification of Stakeholders and Best Practices of Peace-building 9 8. How Conflicts resolved and peace Built between People Living Together According 9 to Stakeholders 9. What Causes Conflicts Both locally and regional/Central? 9 10. Best Practices of Ensuring Women participation in the process 9 11. Best Practices of organising a Peace Conference 10 12. Relations Between Central Regions and Between them TFG 10 13. Table 1: Organisation, Ownership and Legal Structure of the 10 14. Peace Conference 10 15. Conclusion 11 16. Recap 11 16.1 Main Background Points 16.2 Recommendations 16.3 Expected Outcomes of a Peace Conference Main and Detailed Report Page 1. Common geography and History Background of Central Regions 13 1.1 Overview geographical and Environmental Situation 13 1.2 Common History and interdependence 14 1.3 Chronic Neglect of Central Regions 15 1.4 Correlation Between neglect and conflict 15 2. -

This Action Is Funded by the European Union

EN This action is funded by the European Union ANNEX 7 of the Commission Decision on the financing of the Annual Action Programme 2018 – part 3 in favour of Eastern and Southern Africa and the Indian Ocean to be financed from the 11th European Development Fund Action Document for Somalia Regional Corridors Infrastructure Programme (SRCIP) 1. Title/basic act/ Somalia Regional Corridors Infrastructure Programme (SRCIP) CRIS number RSO/FED/040-766 financed under the 11th European Development Fund (EDF) 2. Zone East Africa, Somalia benefiting from The action shall be carried out in Somalia, in the following Federal the Member States (FMS): Galmudug, Hirshabelle, Jubaland, Puntland action/location 3. Programming 11th EDF – Regional Indicative Programme (RIP) for Eastern Africa, document Southern Africa and the Indian Ocean (EA-SA-IO) 2014-2020 4. Sector of Regional economic integration DEV. Aid: YES1 concentration/ thematic area 5. Amounts Total estimated cost: EUR 59 748 500 concerned Total amount of EDF contribution: EUR 42 000 000 This action is co-financed in joint co-financing by: Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) for an amount of EUR 3 500 000 African Development Fund (ADF) 14 Transitional Support Facility (TSF) Pillar 1: EUR 12 309 500 New Partnership for Africa's Development Infrastructure Project Preparation Facility (NEPAD-IPPF): EUR 1 939 000 6. Aid Project Modality modality(ies) Indirect management with the African Development Bank (AfDB). and implementation modality(ies) 7 a) DAC code(s) 21010 (Transport Policy and Administrative Management) - 8% 21020 (Road Transport) - 91% b) Main 46002 – African Development Bank (AfDB) Delivery Channel 1 Official Development Aid is administered with the promotion of the economic development and welfare of developing countries as its main objective. -

Fact Sheet V4

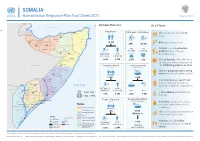

SOMALIA Humanitarian Response Plan Fact Sheet 2021 February 2021 Somalia Overview At a Glance p p! G U L F O F A D E N Caluula Lorem ipsum !p ! Qandala D J I B O U T I Zeylac !p! p Population !pLaasqoray Refugees Returnees Bossaso 69% live on less than $1.90 Awdal ! Ceerigaabo p Lughaye !!p p p a day p! pp Berbera p ! Baki Sanaag ! Iskushuban Borama Woqooyi Ceel Afweyn !! Galbeed !p Sheikh ! Bari p 12.3M Gebiley 40% adult literacy rate p ! p p p Bandarbayla 28K 109.9K !!p !p p ! Odweyne ! Burco ! Qardho pp! ! Hargeysa p Xudun ! !Taleex p Caynabo !p #OF 10,300 recorded protection Togdheer Sool p #OF IDP SITES Laas Caanood PARTNERS incidents from January- p! ! !p p Buuhoodle ! ! Garowe p INTERNALLY NON- December 2020 p p ! DISPLACED DISPLACED Eyl Nugaal ! Burtinle 2.6M 9.7M 2,472 363 20% of Somalis will suffer from !Jariiban ! Galdogob the direct or indirect impacts of Gaalkacyo E T H I O P I A !!p People in Need Food insecurity the COVID19 pandemic in 2021 (2021) (Jan-Jun 2021) ! ! Cadaado Mudug p Cabudwaaq 182,000 pregnant and lactating Dhuusamarreeb !! p women are acutely malnourished Hobyo Galgaduud p ! pp p 5.9M 2.6M p ! Belet Weyne Ceel Buur Ceel Barde !p! Xarardheere ! ! ! 1 in 1,000 women aged 15-49 ! Hiraan p Yeed years in Somalia dies due to ! Bakool Xudur p !!p Doolow ! Ceel Dheer Indian Ocean Bulo Burto pregnancy-related complications Luuq Tayeeglow ! ! ! p! ! Waajid !Adan Yabaal Belet Xaawo p NON- p INTERNALLY K E N Y A Garbahaarey Jalalaqsi !! ! DISPLACED DISPLACED IPC3 IPC4 !Berdale Baidoa Middle ! Gedo !p p Shabelle 2021 -

Somali Fisheries

www.securefisheries.org SECURING SOMALI FISHERIES Sarah M. Glaser Paige M. Roberts Robert H. Mazurek Kaija J. Hurlburt Liza Kane-Hartnett Securing Somali Fisheries | i SECURING SOMALI FISHERIES Sarah M. Glaser Paige M. Roberts Robert H. Mazurek Kaija J. Hurlburt Liza Kane-Hartnett Contributors: Ashley Wilson, Timothy Davies, and Robert Arthur (MRAG, London) Graphics: Timothy Schommer and Andrea Jovanovic Please send comments and questions to: Sarah M. Glaser, PhD Research Associate, Secure Fisheries One Earth Future Foundation +1 720 214 4425 [email protected] Please cite this document as: Glaser SM, Roberts PM, Mazurek RH, Hurlburt KJ, and Kane-Hartnett L (2015) Securing Somali Fisheries. Denver, CO: One Earth Future Foundation. DOI: 10.18289/OEF.2015.001 Secure Fisheries is a program of the One Earth Future Foundation Cover Photo: Shakila Sadik Hashim at Alla Aamin fishing company in Berbera, Jean-Pierre Larroque. ii | Securing Somali Fisheries TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES, TABLES, BOXES ............................................................................................. iii FOUNDER’S LETTER .................................................................................................................... v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................. vi DEDICATION ............................................................................................................................ vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY (Somali) ............................................................................................ -

Rethinking the Somali State

Rethinking the Somali State MPP Professional Paper In Partial Fulfillment of the Master of Public Policy Degree Requirements The Hubert H. Humphrey School of Public Affairs The University of Minnesota Aman H.D. Obsiye May 2017 Signature below of Paper Supervisor certifies successful completion of oral presentation and completion of final written version: _________________________________ ____________________ ___________________ Dr. Mary Curtin, Diplomat in Residence Date, oral presentation Date, paper completion Paper Supervisor ________________________________________ ___________________ Steven Andreasen, Lecturer Date Second Committee Member Signature of Second Committee Member, certifying successful completion of professional paper Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 3 Methodology .......................................................................................................................... 5 The Somali Clan System .......................................................................................................... 6 The Colonial Era ..................................................................................................................... 9 British Somaliland Protectorate ................................................................................................. 9 Somalia Italiana and the United Nations Trusteeship .............................................................. 14 Colonial -

Strengthening Capacity of Eyl District in Puntland to Deliver Services to Citizens

UN Joint Programme for Local Governance and Service Delivery Strengthening Capacity of Eyl District in Puntland to Deliver Services to Citizens Eyl District is situated on the Puntland coast with an estimated population of 130,000, over 220 kilometers from the Puntland state capital, Garowe. In 2012, Eyl District Council was not functioning and was not able to deliver services, leaving residents feeling hopeless about the future. There was no common vision for the delivery of development in the district; residents felt excluded and unable to contribute or influence decisions that affected their lives. The residents of Eyl were known for their involvement in sea-piracy, largely due to their impoverished circumstances. In 2013, JPLG/UNDP collaborated with the Eyl community to mobilize and revive the Eyl District Council. This was achieved through JPLG/UNDP support to the local government to draw up a District Development Framework, providing a five year development vision for the district. This is a component of the Public Planning & Expenditure Management Training, which Eyl District Administration Offices, Puntland strengthens the capacity of Eyl District Council and local government staff, to produce an Annual Work Plan and Budget, providing a framework for the delivery of services in the district. Ely District Planning Officer, Abdinasir Yasin Ali: “The District Development Framework enabled organizations and line ministries in Garowe to work with the Eyl District Council to deliver prioritized services, which has led to the rehabilitation of vital community infrastructure. It has increased the confidence of local govenment staff to carry out their work and helped boost morale in the community.” Representatives from the District Council and District Administration staff worked to produce the District Development Framework, over four months, supported by JPLG/UNDP. -

Export Agreement Coding (PDF)

Peace Agreement Access Tool PA-X www.peaceagreements.org Country/entity Somalia Region Africa (excl MENA) Agreement name Declaration of National Commitment (Arta Declaration) Date 05/05/2000 Agreement status Multiparty signed/agreed Interim arrangement No Agreement/conflict level Intrastate/intrastate conflict ( Somali Civil War (1991 - ) ) Stage Framework/substantive - partial (Multiple issues) Conflict nature Government/territory Peace process 87: Somalia Peace Process Parties The Transnational Government of Somalia Third parties [Note: Several references to the international community] Description Agreement outlines the responsibilities of the Transitional National Assembly, the election of the Chief Justice, the roles of the President and Prime Minister, particularly, the limitations of power of the President. It includes 17-points of binding principles. The Annexes include a ceasefire; a plan of reconstrution and recovery; and the foundations for representation of the Somali population in the TNA and the national dialogue. Agreement document SO_000505_Declaration of national commitment.pdf [] Groups Children/youth No specific mention. Disabled persons No specific mention. Elderly/age No specific mention. Migrant workers No specific mention. Racial/ethnic/national Substantive group [Summary] Contains substantive consideration of inter-group representation in the Transitional National Assembly. Page 1, • Representation in the Conference and in the "Transitional National Assembly" shall be on the basis of local constituencies (regional /clan mix) Page 3, TOWARD THIS END WE ... 8. pledge to place national interest above clan self interest, personal greed and ambitions Page 6, ANNEX IV BASE OF REPRESENTATION IN THE ... WHAT TO GUARD AGAINST • It must be stressed that representation based on clan affiliations or the assumed strength or importance of certain clan, including the size of territories presumed or traditional belonging to certain clans, would only succeed in perpetuating or reinforcing the division of the nation. -

Afmadow District Detailed Site Assessment Lower Juba Region, Somalia

Afmadow district Detailed Site Assessment Lower Juba Region, Somalia Introduction Location map The Detailed Site Assessment (DSA) was triggered in the perspectives of different groups were captured2. KI coordination with the Camp Coordination and Camp responses were aggregated for each site. These were then Management (CCCM) Cluster in order to provide the aggregated further to the district level, with each site having humanitarian community with up-to-date information on an equal weight. Data analysis was done by thematic location of internally displaced person (IDP) sites, the sectors, that is, protection, water, sanitation and hygiene conditions and capacity of the sites and the humanitarian (WASH), shelter, displacement, food security, health and needs of the residents. The first round of the DSA took nutrition, education and communication. place from October 2017 to March 2018 assessing a total of 1,843 sites in 48 districts. The second round of the DSA This factsheet presents a summary of profiles of assessed sites3 in Afmadow District along with needs and priorities of took place from 1 September 2018 to 31 January 2019 IDPs residing in these sites. As the data is captured through assessing a total of 1778 sites in 57 districts. KIs, findings should be considered indicative rather than A grid pattern approach1 was used to identify all IDP generalisable. sites in a specific area. In each identified site, two key Number of assessed sites: 14 informants (KIs) were interviewed: the site manager or community leader and a women’s representative, to ensure Assessed IDP sites in Afmadow4 Coordinates: Lat. 0.6, Long. -

Somalia Hunger Crisis Response.Indd

WORLD VISION SOMALIA HUNGER RESPONSE SITUATION REPORT 5 March 2017 RESPONSE HIGHLIGHTS 17,784 people received primary health care 66,256 people provided with KEY MESSAGES 24,150,700 litres of safe drinking water • Drought has led to increased displacement education. In Somaliland more than 118 of people in Somalia. In February 2017 schools were closed as a result of the alone, UNHCR estimates that up to looming famine. 121,000 people were displaced. • Urgent action at this stage has a high • There is a sharp increase in the number of chance of saving over 300,000 children Acute Water Diarrhoea (AWD/cholera) who are acutely malnourished as well cases. From January to March, 875 AWD as over 6 million people facing possible cases and 78 deaths were recorded in starvation across the country. 22,644 Puntland, Somaliland and Jubaland. • Despite encouraging donor contributions, • There is an urgent need to scale up the Somalia humanitarian operational people provided with support for health interventions in the plan is less than 20% funded (UNOCHA, South West State (SWS) especially FTS, 7th March 2017). Approximately 5,917 in districts that have been hard hit by US$825 million is required to reach 5.5 NFI kits outbreaks of Acute Watery Diarrhoea million Somalis facing possible famine until (AWD). Only few agencies have funding June 2017. to support access to health care services. • More than 6 million people or over 50% • According to Somaliland MOH, high of Somalia’s population remain in crisis cases of measles, diarrhea and pneumonia and face possible famine if aid does not have been reported since November as match the scale of need between now main health complications caused by the and June 2017. -

Protection Cluster Update Weekly Report

Protection Cl uster Update Funded by: The People of Japan Weeklyhttp://www.shabelle.net/article.php?id=4297 Report 30 th March 2012 European Commission IASC Somalia •Objective Protection Monitoring Network (PMN) Humanitarian Aid This update provides information on the protection environment in Somalia, including apparent violations of Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law as reported during the last two weeks through the IASC Somalia Protection Cluster monitoring systems. Incidents mentioned in this report are not exhaustive. They are intended to highlight credible reports to inform and prompt programming and advocacy initiatives by the humanitarian community and national authorities. GENERAL OVERVIEW During the reporting period, fighting continued between Al-Shabaab forces and forces supporting the Transitional Federal Government (TFG) in Lower Juba, Banadir and Bakool regions resulting in the displacement of people, mainly within these regions and an unknown number of civilian casualties. Heavy fighting erupted between Al Shabaab and Ethiopian forces in Xudur district of Bakool region. The heavy fighting resulted in an unconfirmed number of casualties and the occupation of Xudur district by the pro-TFG forces who subsequently imposed a night-time curfew.1 Indiscriminate attacks against the civilian population, including IDPs remained a major concern over the past two weeks. At least 11 people were killed and 12 others injured during the past two weeks owing to mortars landing in Beerta Darawiishta IDP settlements of Banadir region. Al Shabaab forces are reported to have instructed IDPs to move away from areas surrounding the presidential palace as they intended to continue their attacks. 2 Fighting also erupted between Al Shabaab and Ahlul Sunna Wal-jama’a (ASWJ) in Dhuusamarreeb district of Galgaduud region resulting with approximately 300 displacements arriving mainly in Gaalkacyo district of Mudug and Garowe district of Nugaal region.