Enhanced Enrolment of Pastoralists in the Implementation and Evaluation of the UNICEF-FAO-WFP Resilience Strategy in Somalia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti

Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti DISSERTATION ZUR ERLANGUNG DER GRADES DES DOKTORS DER PHILOSOPHIE DER UNIVERSTÄT HAMBURG VORGELEGT VON YASIN MOHAMMED YASIN from Assab, Ethiopia HAMBURG 2010 ii Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti by Yasin Mohammed Yasin Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (POLITICAL SCIENCE) in the FACULITY OF BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES at the UNIVERSITY OF HAMBURG Supervisors Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff HAMBURG 15 December 2010 iii Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my doctoral fathers Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit and Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff for their critical comments and kindly encouragement that made it possible for me to complete this PhD project. Particularly, Prof. Jakobeit’s invaluable assistance whenever I needed and his academic follow-up enabled me to carry out the work successfully. I therefore ask Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit to accept my sincere thanks. I am also grateful to Prof. Dr. Klaus Mummenhoff and the association, Verein zur Förderung äthiopischer Schüler und Studenten e. V., Osnabruck , for the enthusiastic morale and financial support offered to me in my stay in Hamburg as well as during routine travels between Addis and Hamburg. I also owe much to Dr. Wolbert Smidt for his friendly and academic guidance throughout the research and writing of this dissertation. Special thanks are reserved to the Department of Social Sciences at the University of Hamburg and the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) that provided me comfortable environment during my research work in Hamburg. -

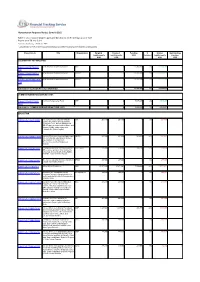

Grouped by Cluster

Humanitarian Response Plan(s): Somalia 2015 Table E: List of appeal projects (grouped by Cluster), with funding status of each Report as of 28-Sep-2021 http://fts.unocha.org (Table ref: R##) Compiled by OCHA on the basis of information provided by donors and recipient organizations. Project Code Title Organization Original Revised Funding % Unmet Outstanding requirements requirements USD Covered requirements pledges USD USD USD USD CLUSTER NOT YET SPECIFIED SOM-15/SNYS/78452/ to be allocated to specific projects WFP 0 0 15,200,048 0% -15,200,048 0 561 SOM-15/SNYS/78471/ to be allocated to specific projects UNHCR 0 0 22,776,204 0% -22,776,204 0 120 SOM-15/SNYS/78658/R/ to be allocated to specific projects UNICEF 0 0 13,712,399 0% -13,712,399 0 124 Sub total for CLUSTER NOT YET SPECIFIED 0 0 51,688,651 0% -51,688,651 0 COMMON HUMANITARIAN FUND (CHF) SOM-15/SNYS/77965/ Common Humanitarian Fund CHF 0 0 9,595,257 0% -9,595,257 0 7622 Sub total for COMMON HUMANITARIAN FUND (CHF) 0 0 9,595,257 0% -9,595,257 0 EDUCATION SOM-15/E/71574/8380 Increasing Access & Quality of Basic JCC 201,150 201,150 0 0% 201,150 0 Literacy for Children and Adults from Vulnerable, Poor, Women Headed and IDP / Returness Households in Bu'ale and Salagle (Middle Jubba region) and Celbarde-Ato (Bakool region) SOM-15/E/71608/14579 Improved Protective Learning Spaces and FENPS 451,400 451,400 289,999 64% 161,401 0 Access to Quality Education for School Age Children in Humanitarian Emergencies and Conflict Areas in Somalia SOM-15/E/71628/5660 Emergency education for crises-affected -

Reserve 2016 Direct Beneficiaries : Men Women Boys Girls Total 0 500 1

Requesting Organization : CARE Somalia Allocation Type : Reserve 2016 Primary Cluster Sub Cluster Percentage Nutrition 100.00 100 Project Title : Emergency Nutritional support for the Acutely malnourished drought affected population in Qardho and Bosaso Allocation Type Category : OPS Details Project Code : Fund Project Code : SOM-16/2470/R/Nut/INGO/2487 Cluster : Project Budget in US$ : 215,894.76 Planned project duration : 8 months Priority: Planned Start Date : 01/05/2016 Planned End Date : 31/12/2016 Actual Start Date: 01/05/2016 Actual End Date: 31/12/2016 Project Summary : This Project is designed to provide emergency nutrition assistance that matches immediate needs of drought affected women and children (boys and girls) < the age of 5 years in Bari region (Qardho and Bosaso) that are currently experiencing severe drought conditions. The project will prioritize the management of severe acute malnutrition and Infant and Young child Feeding (IYCF) and seeks to provide emergency nutrition assistance to 2500 boys and girls < the age of 5 years and 500 pregnant and lactating women in the drought affected communities in Bosaso and Qardho. Direct beneficiaries : Men Women Boys Girls Total 0 500 1,250 1,250 3,000 Other Beneficiaries : Beneficiary name Men Women Boys Girls Total Children under 5 0 0 1,250 1,250 2,500 Pregnant and Lactating Women 0 500 0 0 500 Indirect Beneficiaries : Catchment Population: 189,000 Link with allocation strategy : The project is designed to provide emergency nutrition support to women and children that are currently affected by the severe drought conditions. The proposed nutrition interventions will benefit a total of 2500 children < the age of 5 years and 500 Pregnant and lactating women who are acutely malnourished. -

Awdal Region - Completed Activities Jan-Dec 2012 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Lawya ! ! ! Caddo 43°0'E 43°30'E 44°0'E ! ! ! ! El Qori Sacadiin ! ! ! Bariisle ( Island) ! ! !

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! WASH CLUSTER - Awdal Region - Completed Activities Jan-Dec 2012 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Lawya ! ! ! Caddo 43°0'E 43°30'E 44°0'E ! ! ! ! El Qori Sacadiin ! ! ! Bariisle ( Island) ! ! ! ! ! Muliyo ! ! ! ! ! Zeylac ! ! ! ! ! ! Toqos!hi ! Zeylac ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Waraabood ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! A!WDAL ! ! ! ! Doon Jaglaleh ! ! ! ! ! Caasha ! ! ! ! ! ! Caddo ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Xirsi ! Bow! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Odawaa ! ! ! ! ZEYLAC !Dari ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! N N ! ' ' ! ! ! ! ! 0 0 ! ! ! ° ° ! ! ! ! ! ! 1 1 Cali Ceel ! ! ! ! ! ! 1 Harag Jiid 1 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !Weeci Gaal ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !Haren ! ! ! Dudub ! ! ! Laan Cawaale ! Heensa Asa ! Laan Shinbirood ! ! ! ! ! ! Qumbo ! !Guutooyinka ! Camuud ! ! ! Wareen ! ! ! C!ulus ! ! ! ! Fulla ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! !Iskudarka ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! Cammuud Culus !! ! ! ! ! Bulo ! Sh.Ciise ! ! ! ! ! Karuure ! ! !Xareed ! Heemaal ! ! ! ! Xidhxid Galbeed ! ! !Cadde ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Garaaca ! ! ! X!oore ! ! ! Lughaye ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !Bullo Qoxle Lughaye ! ! !Xajiinle ! ! !Hadhwanaag ! Beeyo ! ! ! Beeyo ! ! ! Maame! !Liiban Macaan ! HEAL LUGHAYE ! ! Nuur ! ! Carmaale ! ! G!ahayr !! ! ! Odawaa ! ! ! ! ! Ido-Cadeys !Geerisa Heemaal ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Dheere Hadeytacawl Biyo ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Cas!e !! ! ! Hadayta ! ! ! Haydeeta ! ! Baxarsaas Heemaal ! !Xussein ! ! ! Weyn ! Baxara Kalawle ! ! Sheikh Awaare Biyo-Cas -

September 29, 2005 Parliamentary Election Assessment Report

International Republican Institute Suite 700 1225 Eye St., NW Washington, D.C. 20005 (202) 408-9450 (202) 408-9462 FAX www.iri.org International Republican Institute Somaliland September 29, 2005 Parliamentary Election Assessment Report Table of Contents Map of Somaliland……………………………………………………………………..….2 Executive Summary…………………………………………………………………….....3 I. Background Information.............................................................................................…..5 II. Legal and Administrative Framework………………………………..………..……….8 III. Pre-Election Period……………. …...……………………………..…………...........12 IV. Election Day…………...…………………………………………………………….18 V. Post-Election Period and Results.…………………………………………………….27 VI. Findings and Recommendations……………………………………………………..33 VII. Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………..38 Appendix A: Voting Results in 2005 Presidential Elections…………………………….39 Appendix B: Voting Results in 2003 Presidential Elections…………………………….41 Appendix C: Voting Results in 2002 Local Government Elections……………………..43 Appendix D: Voting Trends……………………………………………………………..44 IRI – Somaliland September 29, 2005 Parliamentary Election Assessment Report 1 Map of Somaliland IRI – Somaliland September 29, 2005 Parliamentary Election Assessment Report 2 Executive Summary Background The International Republican Institute (IRI) has conducted programs in Somaliland since 2002 with the support of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the U.S. Department of State, and the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). IRI’s Somaliland -

Assessment Report 2011

ASSESSMENT REPORT 2011 PHASE 1 - PEACE AND RECONCILIATION JOIN- TOGETHER ACTION For Galmudug, Himan and Heb, Galgaduud and Hiiraan Regions, Somalia Yme/NorSom/GSA By OMAR SALAD BSc (HONS.) DIPSOCPOL, DIPGOV&POL Consultant, in collaboration with HØLJE HAUGSJÅ (program Manager Yme) and MOHAMED ELMI SABRIE JAMALLE (Director NorSom). 1 Table of Contents Pages Summary of Findings, Analysis and Assessment 5-11 1. Introduction 5 2. Common Geography and History Background of the Central Regions 5 3. Political, Administrative Governing Structures and Roles of Central Regions 6 4. Urban Society and Clan Dynamics 6 5. Impact of Piracy on the Economic, Social and Security Issues 6 6. Identification of Possibility of Peace Seeking Stakeholders in Central Regions 7 7. Identification of Stakeholders and Best Practices of Peace-building 9 8. How Conflicts resolved and peace Built between People Living Together According 9 to Stakeholders 9. What Causes Conflicts Both locally and regional/Central? 9 10. Best Practices of Ensuring Women participation in the process 9 11. Best Practices of organising a Peace Conference 10 12. Relations Between Central Regions and Between them TFG 10 13. Table 1: Organisation, Ownership and Legal Structure of the 10 14. Peace Conference 10 15. Conclusion 11 16. Recap 11 16.1 Main Background Points 16.2 Recommendations 16.3 Expected Outcomes of a Peace Conference Main and Detailed Report Page 1. Common geography and History Background of Central Regions 13 1.1 Overview geographical and Environmental Situation 13 1.2 Common History and interdependence 14 1.3 Chronic Neglect of Central Regions 15 1.4 Correlation Between neglect and conflict 15 2. -

Briefing Paper

NEW ISSUES IN REFUGEE RESEARCH Working Paper No. 65 Pastoral society and transnational refugees: population movements in Somaliland and eastern Ethiopia 1988 - 2000 Guido Ambroso UNHCR Brussels E-mail : [email protected] August 2002 Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees CP 2500, 1211 Geneva 2 Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.unhcr.org These working papers provide a means for UNHCR staff, consultants, interns and associates to publish the preliminary results of their research on refugee-related issues. The papers do not represent the official views of UNHCR. They are also available online under ‘publications’ at <www.unhcr.org>. ISSN 1020-7473 Introduction The classical definition of refugee contained in the 1951 Refugee Convention was ill- suited to the majority of African refugees, who started fleeing in large numbers in the 1960s and 1970s. These refugees were by and large not the victims of state persecution, but of civil wars and the collapse of law and order. Hence the 1969 OAU Refugee Convention expanded the definition of “refugee” to include these reasons for flight. Furthermore, the refugee-dissidents of the 1950s fled mainly as individuals or in small family groups and underwent individual refugee status determination: in-depth interviews to determine their eligibility to refugee status according to the criteria set out in the Convention. The mass refugee movements that took place in Africa made this approach impractical. As a result, refugee status was granted on a prima facie basis, that is with only a very summary interview or often simply with registration - in its most basic form just the name of the head of family and the family size.1 In the Somali context the implementation of this approach has proved problematic. -

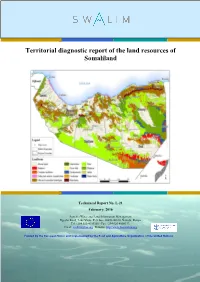

Territorial Diagnostic Report of the Land Resources of Somaliland

Territorial diagnostic report of the land resources of Somaliland Technincal Report No. L-21 February, 2016 Somalia Water and Land Information Management Ngecha Road, Lake View. P.O Box 30470-00100, Nairobi, Kenya. Tel +254 020 4000300 - Fax +254 020 4000333, Email: [email protected] Website: http//www.faoswalim.org Funded by the European Union and implemented by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 1 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the SWALIM Project concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries This document should be cited as follows: Ullah, Saleem, 2016. Territorial diagnostic report of the land resources of Somaliland. FAO-SWALIM, Nairobi, Kenya. 2 Table of Contents List of Acronyms .......................................................................................................................... 7 Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................................ 9 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... 10 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 16 1.1 Background -

Review of Emergency Cash Coordination Mechanisms in the Horn of Africa: Kenya and Somalia

REVIEW OF EMERGENCY CASH COORDINATION MECHANISMS IN THE HORN OF AFRICA: KENYA AND SOMALIA Olivia Collins May 2012 This study has been commissioned by the Cash Learning Partnership Groupe URD (Urgence – Réhabilitation – Développement) provides support to the humanitarian and post-crisis sector. It aims to improve humanitarian practices in favour of crisis-affected people through a variety of activities, such as operational research projects, programme evaluations, the development of methodological tools, organisational support and training both in France and abroad. For more information go to: www.urd.org The Cash Learning Partnership (CaLP) is a consortium of aid organisations which aims to improve knowledge about cash transfer programmes and improve their quality throughout the humanitarian sector. The CaLP was created to gather lessons from post-tsunami relief programmes in 2005. It is currently made up of Oxfam GB, the British Red Cross, Save the Children, Norwegian Refugee Council and Action Against Hunger / ACF International. The 5 organisations that make up the steering committee came together to support capacity building, research and the sharing of experience and knowledge about cash transfer programmes. In 2010 the CaLP established a partnership with the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) in order to develop and implement new activities with funding from ECHO. For more information go to: www.cashlearning.org About the author Olivia Collins is an independent research and evaluation consultant focusing on humanitarian principles and practices. She has a particular interest in innovation and communication within humanitarian coordination systems and the aid architecture as a whole. Olivia has a Masters degree in Humanitarian Action and International Law and is currently studying part-time for a Masters in Social Anthropology. -

Final Evaluation of the Unconditional Cash and Voucher Response to the 2011–12 Crisis in Southern and Central Somalia

Final Evaluation of the Unconditional Cash and Voucher Response to the 2011–12 Crisis in Southern and Central Somalia Report Humanitarian Outcomes team comprised of: Kerren Hedlund, Nisar Majid, Dan Maxwell, and Nigel Nicholson This evaluation was commissioned by UNICEF. The evaluation process was guided by a steering committee that comprised representatives from: ACTED, DFID, ECHO, FAO, Oxfam, the Somalia Cash Consortium (ACF, Adeso, Danish Refugee Council, Save the Children) and UNICEF. Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this report are those of the evaluation team and do not necessarily represent those of the agencies being evaluated or the evaluation steering committee. The evaluation team takes responsibility for any errors reported herein that are based on its own independent data collection. Final Evaluation of the Unconditional Cash and Voucher Response to the 2011–12 Crisis in Somalia Acknowledgments The evaluation team would like to thank all those who have provided their support and input to this evaluation. We are particularly grateful to the over 30 Somali enumerators, the Somali Women’s Study Centre, Horn Research and Development and Qoran Noor who facilitated interviews with hundreds of Somalis affected by the crisis. We are grateful for the constructive inputs and feedback from the evaluation steering committee; UNICEF, FAO, DFID, ECHO, the Somalia Cash Consortium Coordinator Olivia Collins, Oxfam, and ACTED; the wisdom and advice of Humanitarian Outcomes experts, Paul Harvey and Adele Harmer; and the very open collaboration with Mike Brewin, Sophie Dunn, and Catherine Longley of the ODI team. We are also grateful for the support from the UNICEF country office; Claire Mariani, particularly in her role as evaluation manager, and Jacinta Oluoch, as well as Adeso, the Danish Refugee Council, and Save the Children Somalia for their assistance in organising meetings, workshops and field trips in Nairobi, Mogadishu and Puntland. -

Report of the Tsunami Inter Agency Assessment Mission, Hafun to Gara

TSUNAMI INTER AGENCY ASSESSMENT MISSION Hafun to Gara’ad Northeast Somali Coastline th th Mission: 28 January to 8 February 2005 2 Table of Content Executive Summary .............................................................................................................................................. 5 2. Introduction................................................................................................................................................. 12 2.1 Description of the Tsunami.............................................................................................................. 12 2.2 Description of the Northeast coastline............................................................................................. 13 2.3 Seasonal calendar........................................................................................................................... 14 2.4 Governance structures .................................................................................................................... 15 2.5 Market prices ................................................................................................................................... 16 2.6 UN Agencies and NGOs (local and international) on ground.......................................................... 16 3. Methodology ............................................................................................................................................... 17 4. Food, Livelihood & Nutrition Security Sector......................................................................................... -

Emergency Appeal Operations Update Somalia: Tropical Cyclone

Emergency appeal operations update Somalia: Tropical cyclone Emergency appeal n° MDRSO002 GLIDE n° TC – 2013-000140-SOM Operations update n° 2 Timeframe covered by this update: 10 January 2014 – 5 February 2014 Emergency Appeal operation start date: 20 Timeframe: 9 months and end date September 2014 December 2013 Appeal budget: CHF Appeal coverage: Total estimated Red Cross and Red Crescent 2,406,038 18 % response to date: CHF 426,817 Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) allocated: 67,841 N° of people being assisted: 23,100 (3,300 households) Host National Society presence (n° of volunteers, staff, branches): 50 volunteers, 40 staff and 2 SRCS Branches (Garowe and Bosaso) Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners actively involved in the operation: Somali Red Crescent Society (SRCS), IFRC, ICRC Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: WFP,UNICEF,UNHCR,FAO,UNFPA, World Vision, CARE, NRC, DRC, IOM, FINAID, ADESO Summary: On Sunday 10 November 2013, the State of Puntland was hit by a tropical cyclone, followed by very heavy rains and flash floods. The cyclone caused loss of human lives and the destruction of assets including livestock and fishing boats, destroyed numerous settlements, service centers, roads, schools, communication and electrical installations. The most affected areas included, Dangorayo, Bandar Beyla, Garowe and Eyl districts. Other areas affected include the coastal villages in Bari region including Hafun, Iskushuban, Bargal, Qandala and Allula districts. With the support of IFRC and the start-up loan provided through the DREF operation, the Somali Red Crescent Society (SRCS) undertook a detailed assessment in the affected areas in Nugaal and Bari regions.