A Handful of Images Is As Good As an Armful of Arguments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Only (Self)Portrait of Quaglio and the Consequences of Its Renovation

Varstvo spomenikov, 44 Mateja Neža Sitar The Only (Self)Portrait of Quaglio and the Consequences of its Renovation Key words: Ljubljana cathedral, Giulio Quaglio, self-portrait, monument preservation service, conser- vation and restoration procedures, Baroque painting technique, removal of impurities, retouching Abstract In the early 18th century, in the heyday of Baroque art in Ljubljana, the dean and patron of the construc- tion of the new Ljubljana cathedral, Janez Anton Dolničar, commissioned the northern Italian painter Giulio Quaglio (1668–1751) to adorn the cathedral of St Nicholas with frescoes. The Lombard Baroque painter, who was born in Laino on Lake Como, was a distinguished mural painter in Friuli and Gorizia, and he created his greatest masterpiece of his virtuoso artistic career in the illusionist murals in the inte- rior and on the exterior of the Ljubljana cathedral (1703–1706). Later, in 1721–1723, he returned with his son and completed the murals in the chapels of the nave. At that time the frescoes in the Ljubljana cathedral represented one of the largest cycles in Slovenia, and moreover, they were the most important commission of the artist. Because of this, he added his self-portrait to the images, which, according to research, is the only such example in his oeuvre in Italy, Austria and Slovenia. In 2002 a team from the Restoration Centre initiated one of its most complex and demanding conserva- tion and restoration projects on approximately 532 square metres of murals on the vault and western wall of the Ljubljana cathedral. The difficulty level of the project is evident from the methodology and organisation of the four-year work process, which in addition to concrete restoration procedures on the murals also entailed ongoing research, analysis, verification, study and documentation from various ex- pert points of view. -

21 CHAPTER I the Formation of the Missionary Gaspar's Youth The

!21 CHAPTER I The Formation of the Missionary Gaspar’s Youth The Servant of God was born on January 6, 1786 and was baptized in the parochial church of San Martino ai Monti on the following day. On that occasion, he was given the names of the Holy Magi since the solemnity of the Epiphany was being celebrated. I received this information from the Servant of God himself during our familiar conversations. The Servant of God’s parents were Antonio Del Bufalo and Annunziata Quartieroni. I likewise learned from conversation with the father of the Servant of God as well as from him that at first Antonio was engaged in work in the fields but later, when his income was running short, he applied as a cook in service to the most excellent Altieri house. The Del Bufalos were upright people and were endowed sufficiently for their own maintenance as well as that of the family. They had two sons: one was named Luigi who married the upright young lady Paolina Castellini and were the parents of a daughter whose name was Luigia. The other son, our Servant of God. Luigi and Gaspar’s sister-in-law, as well as his father and mother, are now deceased. As far as I know, the aforementioned parents were full of faith, piety and other virtues made know to me not only by the Servant of God, honoring his father and mother, but also by Monsignor [Antonio] Santelli who was the confessor of his mother and a close friend of the Del Bufalo family. -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p. -

Ljubljana Tourism

AKEYTOLJUBLJANA MANUAL FOR TRAVEL TRADE PROFESSIONALS Index Ljubljana 01 LJUBLJANA 02 FACTS 03 THE CITY Why Ljubljana ............................................................. 4 Numbers & figures.............................................. 10 Ljubljana’s history ................................................ 14 Ljubljana Tourism ................................................... 6 Getting to Ljubljana ........................................... 12 Plečnik’s Ljubljana ............................................... 16 Testimonials .................................................................. 8 Top City sights ......................................................... 18 City map ........................................................................... 9 ART & RELAX & 04 CULTURE 05 GREEN 06 ENJOY Art & culture .............................................................. 22 Green Ljubljana ...................................................... 28 Food & drink .............................................................. 36 Recreation & wellness .................................... 32 Shopping ...................................................................... 40 Souvenirs ..................................................................... 44 Entertainment ........................................................ 46 TOURS & 07 EXCURSIONS 08 ACCOMMODATION 09 INFO City tours & excursions ................................ 50 Hotels in Ljubljana .............................................. 58 Useful information ............................................ -

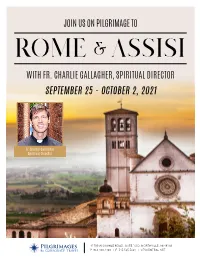

October 2, 2021

JOIN US ON PILGRIMAGE TO ROME & ASSISI WITH FR. CHARLIE GALLAGHER, SPIRITUAL DIRECTOR SEPTEMBER 25 - OCTOBER 2, 2021 Fr. Charlie Gallagher Spiritual Director 41780 W Six Mile Road, Suite 1oo, Northville, MI 48168 P: 866.468.1420 | F: 313.565.3621 | ctscentral.net READY TO SEE THE WORLD? PRICING STARTS AT $2,899 PER PERSON, DOUBLE OCCUPANCY PRICE REFLECTS A $100 PER PERSON EARLY BOOKING SAVINGS FOR DEPOSITS RECEIVED BEFORE APRIL 1, 2021 & A $90 DISCOUNT FOR THOSE PAYING THE TOTAL COST OF THE TOUR BY E-CHECK BOOK NOW BY VISITING: WWW.CTSCENTRAL.NET/IMMACULATECONCEPTION-GALLAGHER-ITALY-202109 QUESTIONS? VISIT CTSCENTRAL.NET TO BROWSE OUR FAQ’S OR CALL 866.468.1420 TO SPEAK TO A RESERVATIONS SPECIALIST. Day 1: Saturday, September 25 - Depart USA Depart on overnight flights to Rome, Italy. Day 2: Sunday, September 26 - Rome • Assisi Arrive in Rome and meet your Italian tour manager. Transfer to Assisi via private coach. Celebrate opening Mass upon arrival at St. Mary of the Angels and see the Porziuncula of St. Francis. Enjoy a group welcome dinner and overnight in Assisi. Day 3: Monday, September 27 - Assisi Celebrate Mass this morning at St. Francis Basilica, see the crypt where he is buried followed by time for prayer and a tour. Take a walking city tour to see the art and architecture of this Umbrian town. Visit the Church of St. Clare to see her tomb and the San Damiano Cross, and church of San Rufino where St. Francis and St. Clare were baptized. Make a special visit to the tomb of recently beatified Bl. -

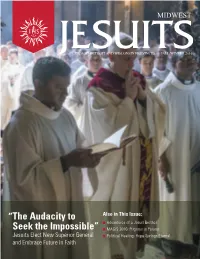

The Audacity to Seek the Impossible” “

MIDWEST CHICAGO-DETROIT AND WISCONSIN PROVINCES FALL/WINTER 2016 “The Audacity to Also in This Issue: n Adventures of a Jesuit Brother Seek the Impossible” n MAGIS 2016: Pilgrims in Poland Jesuits Elect New Superior General n Political Healing: Hope Springs Eternal and Embrace Future in Faith Dear Friends, What an extraordinary time it is to be part of the Jesuit mission! This October, we traveled to Rome with Jesuits from all over the world for the Society of Jesus’ 36th General Congregation (GC36). This historic meeting was the 36th time the global Society has come together since the first General Congregation in 1558, nearly two years after St. Ignatius died. General Congregations are always summoned upon the death or resignation of the Jesuits’ Superior General, and this year we came together to elect a Jesuit to succeed Fr. Adolfo Nicolás, SJ, who has faithfully served as Superior General since 2008. After prayerful consideration, we elected Fr. Arturo Sosa Abascal, SJ, a Jesuit priest from Venezuela. Father Sosa is warm, friendly, and down-to-earth, with a great sense of humor that puts people at ease. He has offered his many gifts to intellectual, educational, and social apostolates at all levels in service to the Gospel and the universal Church. One of his most impressive achievements came during his time as rector of la Universidad Católica del Táchira, where he helped the student body grow from 4,000 to 8,000 students and gave the university a strong social orientation to study border issues in Venezuela. The Jesuits in Venezuela have deep love and respect for Fr. -

1 Catholic Transtemporality Through the Lens of Andrea Pozzo and The

1 Catholic Transtemporality through the Lens of Andrea Pozzo and the Jesuit Catholic Baroque A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Emily C. Thomason August 2020 © 2020 Emily C. Thomason. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled Catholic Transtemporality through the Lens of Andrea Pozzo and the Jesuit Catholic Baroque by EMILY C. THOMASON has been approved for the School of Art + Design and the College of Fine Arts by Samuel Dodd Lecturer, School of Art + Design Matthew R. Shaftel Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 Abstract THOMASON, EMILY C, M.A., August 2020, Art History Catholic Transtemporality through the Lens of Andrea Pozzo and the Jesuit Catholic Baroque Director of Thesis: Samuel Dodd Andrea Pozzo was a lay brother for the Order of the Society of Jesus in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries who utilized his work in painting, architecture, and writing to attempt to create an ideal expression of sacred art for the Counter- Reformation Catholic Church. The focus of this study is on Pozzo’s illusionary paintings in Chiesa di Sant’Ignazio di Loyola in Rome as they coincide with his codification of quadratura and di sotto in su, as described through perspectival etchings and commentary in Perspectiva Pictorum et Architectorum. This thesis seeks to understand the work of Pozzo in context with his Jesuit background, examining his work under the lens of Saint Ignatius of Loyola’s Spiritual Exercises, as well as the cultural, political, and religious climates of Rome during the Counter-Reformation era. -

A Geological Tour of Ljubljana 3

Natural stone in cultural monuments A geological tour of Ljubljana 3 4 2 5 1 16 6 15 8 7 17 9 14 10 11 13 12 SBy pozornim being observant opazovanjem while strollinglahko nathe sprehodu streets of po Ljubljana, ljubljanskih one can ulicahrecognize spoznate many številnetypes of vrste rocks kamninand fossils. in fosilov. 11 PrešernovPrešernov trgTrg Square 22 PalačaDeželna Deželne banka Slobankevenije Building 33 BambergovaBamberg House hiša 44 Nebotičnik (Skyscraper) 55 StavbaParliament Parlamenta Building 66 TrgTrg republikeRepublike Square 77 CankarjevCankarjev domDom 88 HribarjevoHribarjevo nabrežjNabrežjee Quay 99 UniverzaUniversity v ofLjubljani Ljubljana 10 10 NarodnaNational inand univerzitetna University Library knjižnica (NUK) 11 11 Križanke 12 12 RimskiRoman zid Wall na inMirju Mirje 13 13 LevstikovLevstikov trgTrg Square 14 14 LjubljanskiLjubljana Castle grad 15 15 LjubljanskaLjubljana Ca stolnicathedral inand Semenišče Seminary Palace 16 16 PlečnikovePlečnik’s Marke tržnict eHalls 17 17 Mestni trgTrg Square TheVodnik guide po to 21 thetipih 21 slovenskih Slovenian inand 8 tipih 8 foreign tujih rockkamnin, types, 11 skupinah as well as fosilov 11 fossil in 2groups tektonskih and 2 tectonicstrukturah structures v mestnem in jedruLjubljana’s Ljubljane. city centre. Prešernov Trg 1 Square Prešeren Monument A monument to France Prešeren, Slovenia’s greatest poet, 1905. The monument is made of three types of stone. The low base is made of Podpeč limestone (→ 4, 10, 13, 17). The large, dark, cuboid-shaped pedestals are made of Jablanica gabbro from the Neretva River Valley; it used to be one of the most sought-after stones types, but the quarry is now closed. The light- coloured upper part is made of Permian Baveno granite, quarried in Carinthia or northern Italy. -

113-Sant'andrea Al Quirinale

(113/12) Sant'Andrea al Quirinale Sant'Andrea al Quirinale is the 17th century former convent church, now titular, of the Jesuit novitiate, and is located at Via del Quirinale 29 in the rione Monti. The dedication is to St Andrew the Apostle. [1] History The first church on the site, Sant'Andrea in Monte Cavallo, was a parish church. The then abandoned church and land was donated to the General of the Jesuits, St Francis Borgia, by Giovanni Andrea Croce, Bishop of Tivoli, in the 16th century, and became the church of the Society's novitiate. [1] [a] It was in 1567 that the young Polish nobleman Stanislas Kostka walked to Rome from Vienna, taking up residence at the new novitiate, only to die there i8 months later. [a] The present church on the Quirinal was begun in 1658 with funds provided by Cardinal Camillo Pamphilj. The body of the present church was built in 1658–1661. Bernini designed it, but he left the actual work of construction to a brilliant committee of architects and artists among whom were Maa de' Rossi and Antonio Raggi. The interior was decorated over the long period between 166o and 1672. The whole building was finally finished and consecrated in 1678. [1] [a] (113/12) The church is considered one of the finest examples of Roman Baroque with its superb balance and harmony in the choice of materials and the flow of light. It is said that Bernini did not charge a fee for designing this church, and his only payment was a daily donation of bread from the novitiate's oven. -

Rome Architecture Guide 2020

WHAT Architect WHERE Notes Zone 1: Ancient Rome The Flavium Amphitheatre was built in 80 AD of concrete and stone as the largest amphitheatre in the world. The Colosseum could hold, it is estimated, between 50,000 and 80,000 spectators, and was used The Colosseum or for gladiatorial contests and public spectacles such as mock sea Amphitheatrum ***** Unknown Piazza del Colosseo battles, animal hunts, executions, re-enactments of famous battles, Flavium and dramas based on Classical mythology. General Admission €14, Students €7,5 (includes Colosseum, Foro Romano + Palatino). Hypogeum can be visited with previous reservation (+8€). Mon-Sun (8.30am-1h before sunset) On the western side of the Colosseum, this monumental triple arch was built in AD 315 to celebrate the emperor Constantine's victory over his rival Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge (AD 312). Rising to a height of 25m, it's the largest of Rome's surviving ***** Arch of Constantine Unknown Piazza del Colosseo triumphal arches. Above the archways is placed the attic, composed of brickwork revetted (faced) with marble. A staircase within the arch is entered from a door at some height from the ground, on the west side, facing the Palatine Hill. The arch served as the finish line for the marathon athletic event for the 1960 Summer Olympics. The Domus Aurea was a vast landscaped palace built by the Emperor Nero in the heart of ancient Rome after the great fire in 64 AD had destroyed a large part of the city and the aristocratic villas on the Palatine Hill. -

Curriculum Vitae |

Curriculum Vitae Stefano Del Bove, Ph.D., S.J. Age 48 Italian Citizenship JESUIT LIFE ADMISSION TO NOVICIATE - 1994, Genoa, Italy. THEOLOGY - 2000, Collegio Internationale del Gesù and PUG, Rome, Italy. PRIESTLY ORDINATION - 2004, Church of the Gesù, Rome, Italy, (ceremony presided by archbishop, Giuseppe Pittau sj). SPECIAL STUDIES - 2004, Fordham University, NYC, US. TERTIANSHIP - 2015, Santiago, Chile, (instructor fr. Juan Diaz sj). FINAL VOWS - 2017, Church of the Gesù, Rome, Italy, (ceremony presided by Father General, Arturo Sosa sj). MISSION TO THE PONTIFICAL GREGORIAN UNIVERSITY (PUG) - January 7th, 2019. LANGUAGES Italian (native), American-English (advanced, professional), French (conversational, advanced readings), Spanish (advanced in all skills), Latin (basic), Biblical Greek (basic). CERTIFICATIONS Spanish language and Latin American Studies course attendance, Loyola University Chicago (Fall, 2014). Asian Studies, Sophia University, Tokyo, Japan (Summer, 2005), in English. International Jesuit Educational Leadership Project, Warsaw, Poland (Summer, 2003 and 2004), in English. Curso de Función Académica y Sistemas de Evaluación Escolar, CONEDSI, Salamanca, Spain (Summer, 2003), in Spanish. Course de Langue et Civilisation Française, Paris, France (Summer, 1996). REFERENCES - Furnished on request. 1/10 I. ADMINISTRATIVE EXPERIENCE IN HIGHER EDUCATION Liaison officer and student advisor 2015-2019 - State University of Trieste, RTM Living Residence and Campus Opening and operating an office to put students, faculty and administrators in touch with the Jesuit Higher Education network, to advice students on making international their career of study and research, to connect them with the Veritas Cultural Center and the Villa Ara Youth Center, to network with a number of global institute of research, corporation and academic institutions as on the occasion of the visit of: o Father General Arturo Sosa on January 2018. -

Jail Mass a First for Bishop, Diocese

ISSN: 0029-7739 $ 1.00 per copy THE OBSERVER Official Newspaper of the Catholic Diocese of Rockford Volume 79 | No. 5 http://observer.rockforddiocese.org FRIDAY JANUARY 10, 2014 Inside Resolve, Refresh, Renew Jail Mass a First for Bishop, Diocese We start the new year with a series of features intended BY AMANDA HUDSON the jail had been long desired to inspire you to resolve to News editor and long planned and added, “I refresh and renew yourself, think it is important for me as both physically and spiritually. ROCKFORD—“It was real the bishop of the diocese to be The fi rst features are in this nice,” one of the men said at the (here) with you.” issue. Look for more through- conclusion of a Christmas Day His homily spoke of the out the next few weeks. Mass held for him and other “something better than all of prisoners in surroundings that the pain and sorrow” in the were anything but Christmas-y. world, and that “God sent His The monotone jail block set- Son to give each one of us a ting featured no red or green or chance.” anything sparkly. Simple chairs Bishop Malloy noted in par- were set up in rows in front of ticular two messages for this an altar set up at one end of the Christmas day: fi rst, to “keep common area amidst two levels up our hope ... don’t give up of empty cells and storerooms, on God, don’t give up on the their heavy steel doors slightly world, and don’t give up on do- open.