An Analysis of Urban Planning in Ancient Israel a Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Three Conquests of Canaan

ÅA Wars in the Middle East are almost an every day part of Eero Junkkaala:of Three Canaan Conquests our lives, and undeniably the history of war in this area is very long indeed. This study examines three such wars, all of which were directed against the Land of Canaan. Two campaigns were conducted by Egyptian Pharaohs and one by the Israelites. The question considered being Eero Junkkaala whether or not these wars really took place. This study gives one methodological viewpoint to answer this ques- tion. The author studies the archaeology of all the geo- Three Conquests of Canaan graphical sites mentioned in the lists of Thutmosis III and A Comparative Study of Two Egyptian Military Campaigns and Shishak and compares them with the cities mentioned in Joshua 10-12 in the Light of Recent Archaeological Evidence the Conquest stories in the Book of Joshua. Altogether 116 sites were studied, and the com- parison between the texts and the archaeological results offered a possibility of establishing whether the cities mentioned, in the sources in question, were inhabited, and, furthermore, might have been destroyed during the time of the Pharaohs and the biblical settlement pe- riod. Despite the nature of the two written sources being so very different it was possible to make a comparative study. This study gives a fresh view on the fierce discus- sion concerning the emergence of the Israelites. It also challenges both Egyptological and biblical studies to use the written texts and the archaeological material togeth- er so that they are not so separated from each other, as is often the case. -

Building the Temple of Salomo in the Early Medieval „Alamannia“

Journal of Liberal Arts and Humanities (JLAH) Issue: Vol. 1; No. 4; April 2020 pp. 163-185 ISSN 2690-070X (Print) 2690-0718 (Online) Website: www.jlahnet.com E-mail: [email protected] Building the Temple of Salomo in the Early Medieval „Alamannia“ Dr. Thomas Kuentzel M.A. Untere Masch Strasse 16 Germany, 37073 Goettingen E-mail: [email protected] The diocese of Constance is one of the largest north of the Alps, reaching from the Lakes of Thun and Brienz down to Stuttgart and Ulm, from the river Iller (passing Kempten) to the Rhine near Lörrach and Freiburg. Its origins date back to the end of the 6th century; when saint Gall came to the duke of Alamannia, Gunzo, around the year 613, the duke promised him the episcopate, if he would cure his doughter.i In the 9th century some of the bishops also were abbots of the monasteries on the Island Reichenau and of Saint Gall. Three of the bishops were called Salomon, one being the uncle of the following.ii The noble family they belonged to is not known, but they possessed land on the southern shore of Lake Constance, in the province of Thurgau. Salomon III. was educated in the monastery of Saint Gall, and prepared especially for the episcopate. Maybe his uncle and granduncle also benefitted from such an education. Even their predecessor, bishop Wolfleoz, started his career as monk in Saint Gall. It is likely that the three Salomons were given their names with the wish, that they once would gain this office. -

Isurium Brigantum

Isurium Brigantum an archaeological survey of Roman Aldborough The authors and publisher wish to thank the following individuals and organisations for their help with this Isurium Brigantum publication: Historic England an archaeological survey of Roman Aldborough Society of Antiquaries of London Thriplow Charitable Trust Faculty of Classics and the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge Chris and Jan Martins Rose Ferraby and Martin Millett with contributions by Jason Lucas, James Lyall, Jess Ogden, Dominic Powlesland, Lieven Verdonck and Lacey Wallace Research Report of the Society of Antiquaries of London No. 81 For RWS Norfolk ‒ RF Contents First published 2020 by The Society of Antiquaries of London Burlington House List of figures vii Piccadilly Preface x London W1J 0BE Acknowledgements xi Summary xii www.sal.org.uk Résumé xiii © The Society of Antiquaries of London 2020 Zusammenfassung xiv Notes on referencing and archives xv ISBN: 978 0 8543 1301 3 British Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Chapter 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Background to this study 1 Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data 1.2 Geographical setting 2 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the 1.3 Historical background 2 Library of Congress, Washington DC 1.4 Previous inferences on urban origins 6 The moral rights of Rose Ferraby, Martin Millett, Jason Lucas, 1.5 Textual evidence 7 James Lyall, Jess Ogden, Dominic Powlesland, Lieven 1.6 History of the town 7 Verdonck and Lacey Wallace to be identified as the authors of 1.7 Previous archaeological work 8 this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Heritage at Risk

H @ R 2008 –2010 ICOMOS W ICOMOS HERITAGE O RLD RLD AT RISK R EP O RT 2008RT –2010 –2010 HER ICOMOS WORLD REPORT 2008–2010 I TAGE AT AT TAGE ON MONUMENTS AND SITES IN DANGER Ris K INTERNATIONAL COUNciL ON MONUMENTS AND SiTES CONSEIL INTERNATIONAL DES MONUMENTS ET DES SiTES CONSEJO INTERNAciONAL DE MONUMENTOS Y SiTIOS мЕждународный совЕт по вопросам памятников и достопримЕчатЕльных мЕст HERITAGE AT RISK Patrimoine en Péril / Patrimonio en Peligro ICOMOS WORLD REPORT 2008–2010 ON MONUMENTS AND SITES IN DANGER ICOMOS rapport mondial 2008–2010 sur des monuments et des sites en péril ICOMOS informe mundial 2008–2010 sobre monumentos y sitios en peligro edited by Christoph Machat, Michael Petzet and John Ziesemer Published by hendrik Bäßler verlag · berlin Heritage at Risk edited by ICOMOS PRESIDENT: Gustavo Araoz SECRETARY GENERAL: Bénédicte Selfslagh TREASURER GENERAL: Philippe La Hausse de Lalouvière VICE PRESIDENTS: Kristal Buckley, Alfredo Conti, Guo Zhan Andrew Hall, Wilfried Lipp OFFICE: International Secretariat of ICOMOS 49 –51 rue de la Fédération, 75015 Paris – France Funded by the Federal Government Commissioner for Cultural Affairs and the Media upon a Decision of the German Bundestag EDITORIAL WORK: Christoph Machat, Michael Petzet, John Ziesemer The texts provided for this publication reflect the independent view of each committee and /or the different authors. Photo credits can be found in the captions, otherwise the pictures were provided by the various committees, authors or individual members of ICOMOS. Front and Back Covers: Cambodia, Temple of Preah Vihear (photo: Michael Petzet) Inside Front Cover: Pakistan, Upper Indus Valley, Buddha under the Tree of Enlightenment, Rock Art at Risk (photo: Harald Hauptmann) Inside Back Cover: Georgia, Tower house in Revaz Khojelani ( photo: Christoph Machat) © 2010 ICOMOS – published by hendrik Bäßler verlag · berlin ISBN 978-3-930388-65-3 CONTENTS Foreword by Francesco Bandarin, Assistant Director-General for Culture, UNESCO, Paris .................................. -

Castles Along the Rhine; the Middle Rhine

CASTLES ALONG THE RHINE; THE MIDDLE RHINE The Middle Rhine is between Mainz and Cologne (or Köln) but the section of maximum interest for river cruisers is between Koblenz and Rűdesheim. This section is where they keep some of Germany’s best kept medieval keeps - 20 of them, some ruins, some preserved, all surrounded by vineyards and with quaint medieval towns. Around every bend another stone edifice stands watch over the endless parade of freight barges and cruise boats. Each castle has its own spot in Germany’s medieval past. Your river cruise will spend at least an afternoon cruising this section with everyone on deck with a cup of bullion, tea, coffee or a beverage depending on the weather and the cruise director providing commentary on each castle/town you pass. The Rhine gorge castles are bracketed by Germanic / Prussian monuments. At the south end is Rűdesheim with the Niederwalddenkmal monument, commemorating the foundation of the German “Empire” after the Franco- Prussian War. The first stone was laid in 1871, by Wilhelm I. The 38m (123 ft) monument represents the union of all Germans. The central figure is a 10.5 m (34 ft) Germania holding the crown of the emperor in the right hand and in the left the imperial sword. Beneath Germania is a large relief that shows emperor Wilhelm I riding a horse with nobility, the army commanders and soldiers. On the left side of the monument is the peace statue and on the right is the war statue. At the north end in Koblenz is Deutsches Eck (German Corner) where the Mosel and Rhine Rivers meet. -

START of the TOUR 1. Riga Gate the Approximate Area Between

START OF THE TOUR 1. Riga Gate The approximate area between Nikolai 7 (a yellow commercial building) and 12 (a green commercial building), see point 1 on the map. The red contour line on the map marks the town and castle walls in the Hanseatic times. The territory of the castle has been marked with diagonal lines, the area that belonged to the town is marked with dots. The contour line is discontinued at the location of the gate. Towers have been marked with circles, half-towers with semi-circles. The map serves an illustrative purpose. A land route, which was in use already in the 13th century, lead to Riga, starting from the Riga Gate and following the coastline. A more direct route would have been through the Cattle Gate (see point 8 on the map), but the road conditions were better when headed through the Riga Gate. This first point gives a great overview of the entire town wall, moat, towers, other gates, main streets and general image of the town. New-Pärnu was surrounded by a rampart. Read more... This rule did not apply to all medieval towns of the region. There were 9 towns, 2 of them big, on the Estonian territory in medieval times: Tallinn and Tartu, plus 7 smaller towns: Rakvere, Paide, Narva, Viljandi, Haapsalu, New- and Old-Pärnu. Four of those, in turn, belonged to the Hanseatic League: Tallinn, Tartu, Viljandi and New-Pärnu. Other medieval small towns that had town walls around them were Viljandi and Narva (Haapsalu was at least partially surrounded). -

Phase 1A Archaeological Sensitivity Assessment

Phase 1A Archaeological Sensitivity Assessment I-81 Viaduct Project City of Syracuse and Towns of Salina, Cicero, and Dewitt, Onondaga County, New York NYSDOT PIN 3501.60 Prepared for: Prepared by: Environmental Design & Research, Landscape Architecture, Engineering & Environmental Services, D.P.C. 217 Montgomery Street, Suite 1000 Syracuse, New York 13202 P: 315.471.0688 F: 315.471.1061 www.edrdpc.com Redacted Version - November 2016 Phase 1A Archaeological Sensitivity Assessment (redacted version) I-81 Viaduct Project City of Syracuse and Towns of Salina, Cicero, and Dewitt, Onondaga County, New York NYSDOT PIN 3501.60 Prepared for: And Prepared by: Environmental Design & Research, Landscape Architecture, Engineering, & Environmental Services, D.P.C. 217 Montgomery Street, Suite 1000 Syracuse, New York 13202 P: 315.471.0688 F: 315.471.1061 www.edrdpc.com November 2016 MANAGEMENT SUMMARY PIN: 3501.60 NYSORHP Project Review: 16PR06314 DOT Project Type: Highway demolition, reconstruction, and/or replacement Cultural Resources Survey Type: Phase 1A Archaeological Sensitivity Assessment Location Information: City of Syracuse and Towns of Salina, Cicero, and Dewitt Onondaga County Survey Area: Project Description: Reconstruction of I-81 and adjacent roadways in Syracuse, N. The Project is considering 2 alternatives – a Viaduct Alternative and Community Grid Alternative, described herein. Project Area: Area of Potential Effect (APE) for Direct Effects totals 458.9 acres USGS 7.5-Minute Quadrangle Map: Syracuse East, Syracuse West, Jamesville, -

1812; the War, and Its Moral : a Canadian Chronicle

'^^ **7tv»* ^^ / ^^^^T^\/ %*^-'%p^ ^<>.*^7^\/ ^o^*- "o /Vi^/\ co^i^^.% Atii^/^-^^ /.' .*'% y A-^ ; .O*^ . <f,r*^.o^" X'^'^^V %--f.T*\o^^ V^^^^\<^ •^ 4.^ tri * -0 a5 «4q il1 »"^^ 11E ^ ^ THE WAR, AND ITS MORAL CANADIAN CHRONICLE. BY WILLIAM F?"C0FFIN, Esquire, FORMERLT SHERIFF OF THE DISTRICT OF MONTREAI,, LIEUT.-COLONKL, STAFF, ACIITB POROB, CANADA, AND H. M. AGENT FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF THE ORDNANCE ESTATES, CANADA. PRINTED BY JOHN LOVELL, ST. NICHOLAS STREET. 1864. E354 C^y 2. Entered, according to the Act of the Provincial Parliament, in the year one thousand eight hundred and sixty-four, by William F. Coffin, in the OfBce of the Registrar of the Province of Canada. Ea t\}t J^igfjt pjonourable ^ir (SbmtmtJ SSalhtr f cab, iarond, ^er Pajtstg's Post '§ononmbk ^ribg Council, ^nU late ffiobernor ©cneral anli C0mmanKcr4tt=(H;fjicf of IBxitislj Nortfj America, ©Ws (jrattatlinw (!>Uv0uicU 0f the ^m of I8I2 is rcspcctftillp tirtitcatEU, fig fjis fattfjful anU grateful .Scrfaant, WILLIAM P. COFFIN. Ottawa, 2nd January, 1864, TO THE RIGHT HONORABLE SIR EDMUND WALKER HEAD, BARONET. My dear Sir,—^I venture to appeal to your respected name as the best introduction for the little work which I" do myself the honour to dedicate to you. To you, indeed, it owes its existence. You conferred upon me the appointment I have the honour to hold under the Crown in Canada, and that appointment has given life to an idea, long cherished in embryo. The management of the Ordnance Lands in this Province has thrown me upon the scenes of the most notable events of the late war. -

Memories of a Golden Age? I25 of Kiriyat Yearim West Ofjerusalem

[ 5 ] M emories of a Golden Age? In the Temple and royal palace of Jerusalem, biblical Israel found its per manent spiritual focus after centuries of struggle and wandering. As the books of Samuel narrate, the anointing of David, son ofJesse, as king over all the tribes oflsrael finalized the process that had begun with God's orig inal promise to Abraham so many centuries before. The violent chaos of the period of the Judges now gave way to a time in which_God's promises could be established securely under a righteous king. Though the first choice for the throne oflsrael had been the brooding, handsome Saul from the tribe of Benjamin, it was his successor David who became the central figure in early Israelite history. Of the fabled King David, songs and stories were nearly without number. They told of his slaying the mighty Goliath with a single sling stone; of his adoption into the royal court for his skill as a harpist; of his adventures as a rebel and freebooter; of his lustful pursuit of Bathsheba; and of his conquests of Jerusalem and a vast empire beyond. His son Solomon, in turn, is remembered as the wisest of kings and the greatest of builders. Stories tell of his brilliant judgments, his unimaginable wealth; and his construction of the great Temple in Jerusalem. For centuries, Bible readers all over the world have looked back to the era of David and Solomon as a golden age in Israel's history. Until recently many scholars have agreed that the united monarchy was the first biblical I2J I24 THE BIBLE UNEARTHED period that could truly be considered historical. -

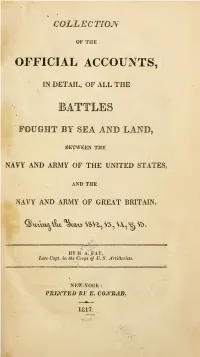

Collection of the Official Accounts, in Detail, of All the Battles Fought By

COLLECTION OF THE OFFICIAL ACCOUNTS, IN DETAIL, OF ALL THE FOUGHT BY SEA AND LAND, BETWEEN THE NAVY AND ARMY OF THE UNITED STATES, AND THE NAVY AND ARMY OF GREAT BRITAIN, BYH A. FAY, Late Capt. in the Corps of U. S. Artillerists. NEW-YORK : PRLYTEJJ Bl £. CO^^BAD, 1817. 148 nt Southern District of Niw-York, ss. BE IT REMEMBERED, that on the twenty-ninth day (if Jpril, m the forty-first year of the Independence of the United States of America, H. A. Fay, of the said District, hath deposited in this office the title ofa book, the right whereof he claims as author and proprietor, in the words andjigures following, to wit: " Collection of the official accounts, in detail, of all the " battles fought, by sea and land, between the navy and array of the United " States, and the nary and army of Great Britain, during the years 1812, 13, " 14, and 15. By H. A. Fay, late Capt. in the corps of U. S. Artillerists."-- In conformity to the Act of Congress of the United States, entitled •' An Act for the encouragement of Learning, by securing the copies of Maps, Charts, and Books to the authors and proprietors of such copies, during the time therein mentioned." And also to an act, entitled " an Act, supplementary to an Act, entitled an Act for the encouragement of Learning, by securing the copies of Maps, Charts, and Books to the authors and proprietors of suck copies, during the times therein mentioned, and extending the benefits thereof to the arts ofdesigning, engraving, and etching historical and other prints." THERON RUDD, Clerk of the Southern District of New-York. -

Battle for the Ruhr: the German Army's Final Defeat in the West" (2006)

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2006 Battle for the Ruhr: The rGe man Army's Final Defeat in the West Derek Stephen Zumbro Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Zumbro, Derek Stephen, "Battle for the Ruhr: The German Army's Final Defeat in the West" (2006). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2507. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2507 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. BATTLE FOR THE RUHR: THE GERMAN ARMY’S FINAL DEFEAT IN THE WEST A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Derek S. Zumbro B.A., University of Southern Mississippi, 1980 M.S., University of Southern Mississippi, 2001 August 2006 Table of Contents ABSTRACT...............................................................................................................................iv INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................................1 -

A-Walk-In-Our-Shoes

2 3 4 Canterbury One of the most historic of English cities, Canterbury is famous for its medieval cathedral. There was a settlement here before the Roman invasion, but it was the arrival of St Augustine in 597 AD that was the signal for Canterbury's growth. Augustine built a cathedral within the city walls, and a new monastery outside the walls. The ruins of St Augustine's Abbey can still be seen today. Initially the abbey was more important than the cathedral, but the murder of St Thomas a Becket in 1170 changed all that. Pilgrims flocked to Canterbury to visit the shrine of the murdered archbishop, and Canterbury Cathedral became the richest in the land. It was expanded and rebuilt to become one of the finest examples of medieval architecture in Britain. But there is more to Canterbury than the cathedral. The 12th century Eastbridge Hospital was a guesthouse for pilgrims, and features medieval wall paintings and a Pilgrim's Chapel. The old West Gate of the city walls still survives, and the keep of a 11th century castle. St Dunstan's church holds a rather gruesome relic; the head of Sir Thomas More, executed by Henry VIII. The area around the cathedral is a maze of twisting medieval streets and alleys, full of historic buildings. Taken as a whole, Canterbury is one of the most satisfying historic cities to visit in England. 5 St Augustine's Abbey In this case the abbey isn't just dedicated to St. Augustine, it was actually founded by him, in 598, to house the monks he brought with him to convert the Britons to Christianity.