The Yom Kippur War: Forty Years Later

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paradigms Sometimes Fit: the Haredi Response to the Yom Kippur War

Paradigms Sometimes Fit: The Haredi Response to the Yom Kippur War CHARLES s. LIEBMAN This essay is an effort to understand Jewish ultra-orthodox Haredi reaction to the 1973 Yom Kippur War. Attention is confined to the large central segment of Haredi society represented in the political arena by Agudat Israel - the only Haredi political party which existed in the period covered here. The hypothesis which guided my research was that between 1973 and the elections of 1977, changes took place in Haredi conceptions of the state of Israel and the wider society which led Agudat Israel to join the government coalition. I have sought to explore this hypothe sis by comparing Haredi responses to the Yom Kippur War with their reactions to the Six Day War of June 1967. I assumed that the striking victory of the Israel Defence Forces (IDF) in the Six Day War would pose serious problems for Haredim. The Six Day War superficially, at least, seemed to be a vindication of Zionism, of secular Israel and the capacity of human design. The Yom Kippur War, on the other hand, seemed to reflect the tentative and insecure status of Israel, its isolation from the world and the folly of Israel's leaders. It, more than any of Israel's wars, might help narrow the sense of alienation that Haredim heretofore have felt. The tragedy and trauma of the war and the deep scars it left in Israeli society would serve, so I anticipated, to evoke in Haredi eyes the age-old experience of the Jewish people since the destruction of the Temple. -

GRAND STRATEGY IS ATTRITION: the LOGIC of INTEGRATING VARIOUS FORMS of POWER in CONFLICT Lukas Milevski

GRAND STRATEGY IS ATTRITION: THE LOGIC OF INTEGRATING VARIOUS FORMS OF POWER IN CONFLICT Lukas Milevski FOR THIS AND OTHER PUBLICATIONS, VISIT US AT UNITED STATES https://www.armywarcollege.edu/ ARMY WAR COLLEGE PRESS Carlisle Barracks, PA and ADVANCING STRATEGIC THOUGHT This Publication SSI Website USAWC Website SERIES The United States Army War College The United States Army War College educates and develops leaders for service at the strategic level while advancing knowledge in the global application of Landpower. The purpose of the United States Army War College is to produce graduates who are skilled critical thinkers and complex problem solvers. Concurrently, it is our duty to the U.S. Army to also act as a “think factory” for commanders and civilian leaders at the strategic level worldwide and routinely engage in discourse and debate concerning the role of ground forces in achieving national security objectives. The Strategic Studies Institute publishes national security and strategic research and analysis to influence policy debate and bridge the gap between military and academia. The Center for Strategic Leadership contributes to the education of world class senior leaders, develops expert knowledge, and provides solutions to strategic Army issues affecting the national security community. The Peacekeeping and Stability Operations Institute provides subject matter expertise, technical review, and writing expertise to agencies that develop stability operations concepts and doctrines. The School of Strategic Landpower develops strategic leaders by providing a strong foundation of wisdom grounded in mastery of the profession of arms, and by serving as a crucible for educating future leaders in the analysis, evaluation, and refinement of professional expertise in war, strategy, operations, national security, resource management, and responsible command. -

The Munich Massacre: a New History

The Munich Massacre: A New History Eppie Briggs (aka Marigold Black) A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of BA (Hons) in History University of Sydney October 2011 1 Contents Introduction and Historiography Part I – Quiet the Zionist Rage 1. The Burdened Alliance 2. Domestic Unrest Part II – Rouse the Global Wrath 3. International Condemnation 4. The New Terrorism Conclusion 2 Acknowledgments I would like to thank first and foremost Dr Glenda Sluga to whom I am greatly indebted for her guidance, support and encouragement. Without Glenda‟s sage advice, the writing of this thesis would have been an infinitely more difficult and painful experience. I would also like to thank Dr Michael Ondaatje for his excellent counsel, good-humour and friendship throughout the last few years. Heartfelt thanks go to Elise and Dean Briggs for all their love, support and patience and finally, to Angus Harker and Janie Briggs. I cannot adequately convey the thanks I owe Angus and Janie for their encouragement, love, and strength, and for being a constant reminder as to why I was writing this thesis. 3 Abstract This thesis examines the Nixon administration’s response to the Munich Massacre; a terrorist attack which took place at the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich. By examining the contextual considerations influencing the administration’s response in both the domestic and international spheres, this thesis will determine the manner in which diplomatic intricacies impacted on the introduction of precedent setting counterterrorism institutions. Furthermore, it will expound the correlation between the Nixon administration’s response and a developing conceptualisation of acts of modern international terrorism. -

War and Diplomacy: the Suez Crisis

1 Professor Pnina Lahav, Boston University School of Law C.) Please do not use, quote or distribute without author’s permission War and Diplomacy: The Suez Crisis 1. Introduction Stephen M. Griffin, Long Wars and the Constitution, and Mariah Zeisberg’s War Powers, are two remarkable books that certainly deserve an entire symposium devoted to them. These books complement each other in the same way that the war powers, some vested in Congress and others in the President, are in correspondence with each other. Griffin’s book revolves around the history of the war powers since 1945, and in this sense is more empirical. Its thesis is that the cold war and Truman’s subsequent decision to launch the war in Korea destabilized American constitutionalism. In the following decades the United States has found itself confronting an endless string of constitutional crises related to the deployment of troops abroad, and the quest for a formula to resolve the constitutional puzzles is as strong as ever. Zeisberg’s book, which took advantage of the fact that Griffin’s book preceded it, is more normative, even though it should be emphasized that Griffin also offers important normative insights. Both books are anchored in democratic theory in that they emphasize the cardinal significance of inter-branch deliberation. Both endorse the notion that the implicit assumption underlying the text of the Constitution is that while the war powers are divided between the legislative and executive branches, these institutions are expected to deliberate internally as well as externally when confronting the critical matter of war. -

Syrian Crisis United Nations Response

Syrian Crisis United Nations Response A Weekly Update from the UN Department of Public Information No. 100/ 24 June 2015 Syrians face “unspeakable suffering,” says UN official The Independent Commission of Inquiry on Syria released on 23 June its latest report on the human rights situation in the country, covering the period from 15 March to 15 June. Presenting the report to the Human Rights Council in Geneva, the Chair of the Commission, Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro, said that the conflict in Syria had mutated into a multi-sided and highly fluid war of attrition and civilians remain the main victims of an ever-accelerating cycle of violence, which is causing “unspeakable suffering.” Mr. Pinheiro added that with its superior fire power and control of the skies, the Government inflicted the most damage in its indiscriminate attacks on civilians, and non- state armed groups continued to cause civilian deaths and injuries. The Chairman of the Commission also deplored that “the continuing war represents a profound failure of diplomacy and the absence of action by the international community had nourished a deeply entrenched culture of impunity.” http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=51227#.VYmoeEbgW3b More funding needed for Palestine refugees in Lebanon On 22 June, UN Special Coordinator for Lebanon, Sigrid Kaag, called for increased donor assistance to the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) to meet the needs of Palestine refugees in Lebanon. Ms. Kaag was speaking during a visit to the Palestinian refugee camp of Burj El-Barajneh, south of Beirut. “Residents of the camp are facing enormous difficulties every day; all possible efforts should be made to give greater support to Palestine refugees here,” she said. -

Palestinian Groups

1 Ron’s Web Site • North Shore Flashpoints • http://northshoreflashpoints.blogspot.com/ 2 Palestinian Groups • 1955-Egypt forms Fedayeem • Official detachment of armed infiltrators from Gaza National Guard • “Those who sacrifice themselves” • Recruited ex-Nazis for training • Fatah created in 1958 • Young Palestinians who had fled Gaza when Israel created • Core group came out of the Palestinian Students League at Cairo University that included Yasser Arafat (related to the Grand Mufti) • Ideology was that liberation of Palestine had to preceed Arab unity 3 Palestinian Groups • PLO created in 1964 by Arab League Summit with Ahmad Shuqueri as leader • Founder (George Habash) of Arab National Movement formed in 1960 forms • Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) in December of 1967 with Ahmad Jibril • Popular Democratic Front for the Liberation (PDFLP) for the Liberation of Democratic Palestine formed in early 1969 by Nayif Hawatmah 4 Palestinian Groups Fatah PFLP PDFLP Founder Arafat Habash Hawatmah Religion Sunni Christian Christian Philosophy Recovery of Palestine Radicalize Arab regimes Marxist Leninist Supporter All regimes Iraq Syria 5 Palestinian Leaders Ahmad Jibril George Habash Nayif Hawatmah 6 Mohammed Yasser Abdel Rahman Abdel Raouf Arafat al-Qudwa • 8/24/1929 - 11/11/2004 • Born in Cairo, Egypt • Father born in Gaza of an Egyptian mother • Mother from Jerusalem • Beaten by father for going into Jewish section of Cairo • Graduated from University of King Faud I (1944-1950) • Fought along side Muslim Brotherhood -

US-China Strategic Competition in South and East China Seas

U.S.-China Strategic Competition in South and East China Seas: Background and Issues for Congress Updated September 8, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R42784 U.S.-China Strategic Competition in South and East China Seas Summary Over the past several years, the South China Sea (SCS) has emerged as an arena of U.S.-China strategic competition. China’s actions in the SCS—including extensive island-building and base- construction activities at sites that it occupies in the Spratly Islands, as well as actions by its maritime forces to assert China’s claims against competing claims by regional neighbors such as the Philippines and Vietnam—have heightened concerns among U.S. observers that China is gaining effective control of the SCS, an area of strategic, political, and economic importance to the United States and its allies and partners. Actions by China’s maritime forces at the Japan- administered Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea (ECS) are another concern for U.S. observers. Chinese domination of China’s near-seas region—meaning the SCS and ECS, along with the Yellow Sea—could substantially affect U.S. strategic, political, and economic interests in the Indo-Pacific region and elsewhere. Potential general U.S. goals for U.S.-China strategic competition in the SCS and ECS include but are not necessarily limited to the following: fulfilling U.S. security commitments in the Western Pacific, including treaty commitments to Japan and the Philippines; maintaining and enhancing the U.S.-led security architecture in the Western Pacific, including U.S. -

Conscious Action and Intelligence Failure

Conscious Action and Intelligence Failure URI BAR-JOSEPH JACK S. LEVY The most famous intelligence mission in biblical times failed be- cause actors made conscious decisions to deliberately distort the information they passed on to their superiors. The 12 spies that Moses sent to the land of Canaan concluded unanimously that the land was good. But estimates by 10 of them that the enemy was too strong and popular pressure by the Israelites who wanted to avoid the risk of fighting a stronger enemy led the 10 spies to consciously change their assessment, from a land that “floweth with milk and honey” to “a land that eateth up the inhabitants thereof.”1 This biblical precedent has been lost among contemporary intelligence analysts, who have traditionally given insufficient attention to the role of de- liberate distortion as a source of intelligence failure. Influenced by Roberta Wohlstetter’s classic study of the American failure to anticipate the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor, by the increasing emphasis in political psychology on motivated and unmotivated biases, and by the literature on bureaucratic poli- tics and organizational processes, students of intelligence failure have em- phasized some combination of a noisy and uncertain threat environment, unconscious psychological biases deriving from cognitive mindsets and emo- tional needs, institutional constraints based on bureaucratic politics and orga- nizational processes, and strategic deception by the adversary.2 1 Num. 13:27–32. 2 Roberta Wohlstetter, Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1962). The key psychological studies include: Leon Festinger, A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1957); Joseph De Rivera, The Psychological Dimension of Foreign Policy (Columbus, OH: Charles E. -

Defense at the Forward Edge of the Battle Or Rather in the Depth? Different Approaches to Implement NATO’S Operation Plans by the Alliance Partners, 1955-1988

Journal of Military and Strategic VOLUME 15, ISSUE 3, 2014 Studies Defense at the Forward Edge of the Battle or rather in the Depth? Different approaches to implement NATO’s operation plans by the alliance partners, 1955-1988 LTC Helmut R. Hammerich Military historians love studying battles. For this purpose, they evaluate operation plans and analyze how these plans were executed on the battlefield. The battle history of the Cold War focuses first and foremost on the planning for the nuclear clash between NATO and the Warsaw Pact. Although between 1945 and 1989-90 the world saw countless hot wars on the periphery of the Cold War, the “Cold World War,” as the German historian Jost Dülffer termed it, is best examined through the operational plans of the military alliances for what would have been World War Three. To conduct such an analysis we must consider Total War under nuclear conditions. Analyzing the war planning, however, is far from easy. The main difficulty lies in access to the files. The records of both the Warsaw Pact and NATO are still largely classified and therefore relatively inaccessible. Nor is access to the archives in Moscow two decades after glasnost and perestroika at all encouraging. At the request of historians, NATO has begun to declassify some of its key documents. Nonetheless, the specific details of the nuclear operational planning will continue to remain inaccessible to historians for the foreseeable future. As an alternative, historians then are forced to rely on collateral documents in the various national archives or on the compilations of ©Centre of Military and Strategic Studies, 2014 ISSN : 1488-559X VOLUME 15, ISSUE 3, 2014 diverse oral history projects. -

Rethinking the Six Day War: an Analysis of Counterfactual Explanations Limor Bordoley

Limor Bordoley Rethinking the Six Day War: An Analysis of Counterfactual Explanations Limor Bordoley Abstract The Six Day War of June 1967 transformed the political and physical landscape of the Middle East. The war established Israel as a major regional power in the region, while the Israeli territorial acquisitions resulting from the war have permanently marred Israel’s relationship with its Arab neighbors. The May crisis that preceded the war quickly spiraled out of control, leading many to believe that the war was unavoidable. In this paper, I construct three counterfactuals that consider how May and June 1967 might have unfolded differently if a particular event or person in the May crisis had been different. Ultimately, the counterfactuals show that war could have been avoided in three different ways, demonstrating that the Six Day War was certainly avoidable. In the latter half of the paper, I construct a framework to compare the effectiveness of multiple counterfactual. Thus, the objective of this paper is twofold: first, to determine whether war was unavoidable given the political climate and set of relations present in May and June 1967 and second, to create a framework with which one can compare the relative persuasiveness of multiple counterfactuals. Introduction The Six Day War of June 1967 transformed the political and physical landscape of the Middle East. The war established Israel as a major regional power, expanding its territorial boundaries and affirming its military supremacy in the region. The Israeli territorial acquisitions resulting from the war have been a major source of contention in peace talks with the Palestinians, and has permanently marred Israel’s relationship with its Arab neighbors. -

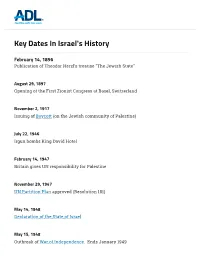

Key Dates in Israel's History

Key Dates In Israel's History February 14, 1896 Publication of Theodor Herzl's treatise "The Jewish State" August 29, 1897 Opening of the First Zionist Congress at Basel, Switzerland November 2, 1917 Issuing of BoBoBoBoyyyycottcottcottcott (on the Jewish community of Palestine) July 22, 1946 Irgun bombs King David Hotel February 14, 1947 Britain gives UN responsibility for Palestine November 29, 1947 UNUNUNUN P PPParararartitiontitiontitiontition Plan PlanPlanPlan approved (Resolution 181) May 14, 1948 DeclarationDeclarationDeclarationDeclaration of ofofof th thththeeee State StateStateState of ofofof Israel IsraelIsraelIsrael May 15, 1948 Outbreak of WWWWarararar of ofofof In InInIndependependependependendendendencececece. Ends January 1949 1 / 11 January 25, 1949 Israel's first national election; David Ben-Gurion elected Prime Minister May 1950 Operation Ali Baba; brings 113,000 Iraqi Jews to Israel September 1950 Operation Magic Carpet; 47,000 Yemeni Jews to Israel Oct. 29-Nov. 6, 1956 Suez Campaign October 10, 1959 Creation of Fatah January 1964 Creation of PPPPalestinalestinalestinalestineeee Liberation LiberationLiberationLiberation Or OrOrOrganizationganizationganizationganization (PLO) January 1, 1965 Fatah first major attack: try to sabotage Israel’s water system May 15-22, 1967 Egyptian Mobilization in the Sinai/Closure of the Tiran Straits June 5-10, 1967 SixSixSixSix Da DaDaDayyyy W WWWarararar November 22, 1967 Adoption of UNUNUNUN Security SecuritySecuritySecurity Coun CounCounCouncilcilcilcil Reso ResoResoResolutionlutionlutionlution -

Theories of Warfare

Theories of Warfare French Operations in Indo-China Author Programme Alexander Hagelkvist Officers Programme, OP 12-15 Tutor Number of pages Stéphane Taillat 71 Scholarship provider: Hosting unit: Swedish National Defence Report date: 2015-06-02 Écoles de Saint-Cyr University Coëtquidan (FRANCE) Subject: War Science Unclassified Institution: CREC (le Centre de Level: Bachelor Thesis Recherche des Écoles de Coëtquidan) Alexander Hagelkvist War science, Bachelor Thesis. “French Operations in Indo-China” Acknowledgements First and foremost I offer my sincerest gratitude to the Swedish Defence University for the scholarship that made my exchange possible. Furthermore to Écoles de Saint-Cyr Coëtquidan for their hospitality, as well as le Centre de Recherche des Écoles de Coëtquidan. I wish to express my sincere thanks to Director Doare, Principal of the Faculty, for providing me with all the necessary facilities for the research. I also want to thank Colonel Renoux for constant support and availability with all the surroundings that concerned my work at the C.R.E.C. And to my supervisor, Stéphane Taillat, who has supported me throughout my thesis with his patience and knowledge whilst allowing me the room to work in my own way. I attribute the completion of my Bachelor thesis to his encouragement and effort and without him this thesis, would not have been completed. I am also grateful to Lieutenant Colonel Marco Smedberg, who has provided me with the interest and motivation for my subject. I am thankful and grateful to him for sharing expertise and valuable guidance. I take this opportunity to express gratitude to Guy Skingsley at the Foreign Languages Section, War Studies at the Swedish Defence University for his help and support on the linguistic parts of the thesis.