Best Practice Guidelines for the Javan Green Magpie Cissa Thalassina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TRUSTVETASSISTSSURVIVAL of WORLD'srarestparrot New Clues to Echo Parakeet Problem Bypallia Harris

News about parrot conservation, aviculture and welfare from qg&%rld q&rrot~t TRUSTVETASSISTSSURVIVAL OF WORLD'SRARESTPARROT New clues to Echo Parakeet problem ByPallIa Harris When the World Parrot Trust was The World Parrot Trust has project, contributing funds and of the World Parrot Trust and a launched in 1989, our first consistently provided funding for parrot expertise to both the member of the International Zoo priority was to help the world's the Echo Parakeet and maintained captive breeding programme and Veterinary Group. When the rarest parrot, the Echo Parakeet, close relations with the project's wild population management captive population of parrots which still numbers less than 20 director, Carl Jones, and the efforts. This new opportunity became ill this spring, Andrew birds in the wild. With your Jersey Wildlife Preservation provides the World Parrot Trust advised project staff in Mauritius generous donations, the Trust Trust, which finances and with one of the greatest by telephone and by fax. was proud to present the Echo manages the project with the co- challenges in parrot conservation Subsequently, at the request of Parakeet project with a badly operation of the Mauritius today. the Jersey Wildlife Preservation needed four wheel drive vehicle government's Conservation Unit. The followingstory is drawn, Trust, the World Parrot Trust sent to enable field researchers to Recently, the World Parrot Trust in part, from a veterinary report Andrew to Mauritius to reach the remote forest in which was invited to become a major by Andrew Greenwood,MAVetMB investigate tragic mortalities the parrot struggles to survive. partner in the Echo Parakeet MIBiolMRCVS,a founder Trustee among the Echo Parakeets. -

Gibbon Journal Nr

Gibbon Journal Nr. 5 – May 2009 Gibbon Conservation Alliance ii Gibbon Journal Nr. 5 – 2009 Impressum Gibbon Journal 5, May 2009 ISSN 1661-707X Publisher: Gibbon Conservation Alliance, Zürich, Switzerland http://www.gibbonconservation.org Editor: Thomas Geissmann, Anthropological Institute, University Zürich-Irchel, Universitätstrasse 190, CH–8057 Zürich, Switzerland. E-mail: [email protected] Editorial Assistants: Natasha Arora and Andrea von Allmen Cover legend Western hoolock gibbon (Hoolock hoolock), adult female, Yangon Zoo, Myanmar, 22 Nov. 2008. Photo: Thomas Geissmann. – Westlicher Hulock (Hoolock hoolock), erwachsenes Weibchen, Yangon Zoo, Myanmar, 22. Nov. 2008. Foto: Thomas Geissmann. ©2009 Gibbon Conservation Alliance, Switzerland, www.gibbonconservation.org Gibbon Journal Nr. 5 – 2009 iii GCA Contents / Inhalt Impressum......................................................................................................................................................................... i Instructions for authors................................................................................................................................................... iv Gabriella’s gibbon Simon M. Cutting .................................................................................................................................................1 Hoolock gibbon and biodiversity survey and training in southern Rakhine Yoma, Myanmar Thomas Geissmann, Mark Grindley, Frank Momberg, Ngwe Lwin, and Saw Moses .....................................4 -

Lobsters-Identification, World Distribution, and U.S. Trade

Lobsters-Identification, World Distribution, and U.S. Trade AUSTIN B. WILLIAMS Introduction tons to pounds to conform with US. tinents and islands, shoal platforms, and fishery statistics). This total includes certain seamounts (Fig. 1 and 2). More Lobsters are valued throughout the clawed lobsters, spiny and flat lobsters, over, the world distribution of these world as prime seafood items wherever and squat lobsters or langostinos (Tables animals can also be divided rougWy into they are caught, sold, or consumed. 1 and 2). temperate, subtropical, and tropical Basically, three kinds are marketed for Fisheries for these animals are de temperature zones. From such partition food, the clawed lobsters (superfamily cidedly concentrated in certain areas of ing, the following facts regarding lob Nephropoidea), the squat lobsters the world because of species distribu ster fisheries emerge. (family Galatheidae), and the spiny or tion, and this can be recognized by Clawed lobster fisheries (superfamily nonclawed lobsters (superfamily noting regional and species catches. The Nephropoidea) are concentrated in the Palinuroidea) . Food and Agriculture Organization of temperate North Atlantic region, al The US. market in clawed lobsters is the United Nations (FAO) has divided though there is minor fishing for them dominated by whole living American the world into 27 major fishing areas for in cooler waters at the edge of the con lobsters, Homarus americanus, caught the purpose of reporting fishery statis tinental platform in the Gul f of Mexico, off the northeastern United States and tics. Nineteen of these are marine fish Caribbean Sea (Roe, 1966), western southeastern Canada, but certain ing areas, but lobster distribution is South Atlantic along the coast of Brazil, smaller species of clawed lobsters from restricted to only 14 of them, i.e. -

Web-Book Catalog 2021-05-10

Lehigh Gap Nature Center Library Book Catalog Title Year Author(s) Publisher Keywords Keywords Catalog No. National Geographic, Washington, 100 best pictures. 2001 National Geogrpahic. Photographs. 779 DC Miller, Jeffrey C., and Daniel H. 100 butterflies and moths : portraits from Belknap Press of Harvard University Butterflies - Costa 2007 Janzen, and Winifred Moths - Costa Rica 595.789097286 th tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA rica Hallwachs. Miller, Jeffery C., and Daniel H. 100 caterpillars : portraits from the Belknap Press of Harvard University Caterpillars - Costa 2006 Janzen, and Winifred 595.781 tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA Rica Hallwachs 100 plants to feed the bees : provide a 2016 Lee-Mader, Eric, et al. Storey Publishing, North Adams, MA Bees. Pollination 635.9676 healthy habitat to help pollinators thrive Klots, Alexander B., and Elsie 1001 answers to questions about insects 1961 Grosset & Dunlap, New York, NY Insects 595.7 B. Klots Cruickshank, Allan D., and Dodd, Mead, and Company, New 1001 questions answered about birds 1958 Birds 598 Helen Cruickshank York, NY Currie, Philip J. and Eva B. 101 Questions About Dinosaurs 1996 Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, NY Reptiles Dinosaurs 567.91 Koppelhus Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, N. 101 Questions About the Seashore 1997 Barlowe, Sy Seashore 577.51 Y. Gardening to attract 101 ways to help birds 2006 Erickson, Laura. Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA Birds - Conservation. 639.978 birds. Sharpe, Grant, and Wenonah University of Wisconsin Press, 101 wildflowers of Arcadia National Park 1963 581.769909741 Sharpe Madison, WI 1300 real and fanciful animals : from Animals, Mythical in 1998 Merian, Matthaus Dover Publications, Mineola, NY Animals in art 769.432 seventeenth-century engravings. -

Traffic.Org/Home/2015/12/4/ Thousands-Of-Birds-Seized-From-East-Java-Port.Html

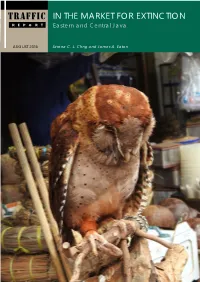

TRAFFIC IN THE MARKET FOR EXTINCTION REPORT Eastern and Central Java AUGUST 2016 Serene C. L. Chng and James A. Eaton TRAFFIC Report: In The Market for Extinction: Eastern and Central Java 1 TRAFFIC REPORT TRAFFIC, the wild life trade monitoring net work, is the leading non-governmental organization working globally on trade in wild animals and plants in the context of both biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. TRAFFIC is a strategic alliance of WWF and IUCN. Reprod uction of material appearing in this report requires written permission from the publisher. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations con cern ing the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views of the authors expressed in this publication are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect those of TRAFFIC, WWF or IUCN. Published by TRAFFIC. Southeast Asia Regional Office Unit 3-2, 1st Floor, Jalan SS23/11 Taman SEA, 47400 Petaling Jaya Selangor, Malaysia Telephone : (603) 7880 3940 Fax : (603) 7882 0171 Copyright of material published in this report is vested in TRAFFIC. © TRAFFIC 2016. ISBN no: 978-983-3393-50-3 UK Registered Charity No. 1076722. Suggested citation: Chng, S.C.L. and Eaton, J.A. (2016). In the Market for Extinction: Eastern and Central Java. TRAFFIC. Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia. Front cover photograph: An Oriental Bay Owl Phodilus badius displayed for sale at Malang Bird Market Credit: Heru Cahyono/TRAFFIC IN THE MARKET FOR EXTINCTION Eastern and Central Java Serene C. -

WHITE-BELLIED HERON REPORT Ardea Insignis Hume, 1878

REPORT WHITE-BELLIED HERON Ardea insignis Hume, 1878 ANNUAL POPULATION SURVEY 2021 Report prepared by Indra Acharja/RSPN [email protected] Summary Introduction The 19 th White-bellied Heron (WBH) annual population survey conducted from 27 February – 03 March 2021 The White-bellied Heron (Ardea insignis Hume 1878) is a large heron species of the family Ardeidae, order counted 22 herons in the country. The survey confirmed 19 adults and three sub-adult individuals, which is five less Pelecaniformes, found in freshwater ecosystems of the Himalayas. It is categorized as critically endangered under than the previous year. The decrease in population was mainly observed in upper Punatsangchhu basin; Phochu, the IUCN Red List of threatened species and protected under the Schedule I of Forests and Nature Conservation Mochhu, Adha and Harachhu which were oldest and previously the most abundantly used habitats in Bhutan. The Act 1995 of Bhutan. It was listed as threatened in 1988, uplisted to endangered in 1994, and to critically endangered survey covered all currently known and expected habitats along Punatsangchhu, Mangdechhu, Chamkharchhu, since 2007. The distribution of WBH to undisturbed freshwater river systems and its piscivorous feeding behaviour Drangmechhu, Kurichhu, Kholongchhu and major tributaries. For the survey, habitats across the country were can be easily associated with the health of the ecosystem and pristinely environment. They are the indicators of our divided into 53 priority zones and surveyors were deployed to look for the WBH from 7:00 AM to 5:00 PM for freshwater river systems. Their presence in our rivers indicates the health of the rivers, the fish population, water five consecutive days within their designated zone. -

Bird Damage to Pistachios

The extent of damage to pistachios by some birds that knock nuts to the ground, where they hull, shell, and eat them, can be measured. Losses to birds that pluck nuts from the tree and fly off to eat them else- where can only be estimated. counties to the south. District I1 (Central) is Merced, Madera, Fresno, and Kings Bird damage to nistachios counties. District I11 (Northern) is Monte- rey, San Benito, Inyo, and all counties to the north of Merced County. Terrell P. Salmon 0 A. Charles Crabb 0 RexE.Marsh Scope of the problem We received 105 responses (23 percent) from the 458 surveys mailed. Thirteen (12.7 percent) were excluded from analy- Crows are the primary culprits sis, because the orchards represented followed by ravens and jays were not in production, were outside Cali- fornia, or were managed by another per- son. The remaining 92 indicated they had pistachio losses due to one or more bird species. Bird damage was widespread through- out the state, as indicated by surveys re- turned from 18 counties. These 18 coun- ties represent 98 percent of the bearing pistachio acreage in California. The infor- mation we report here is based on the sur- vey returns and does not account for bird Various bird species are pests to a step in defining the problem and evaluat- damage and control that undoubtedly oc- number of California crops. Nut crops ing current bird control methods. cur but were not reported. Our estimates such as pistachios, almonds, and walnuts The major focus of the survey was to should therefore be considered conserva- are particularly hard hit, although infor- identify the bird species involved, the ex- tive. -

Records of Four Critically Endangered Songbirds in the Markets of Java Suggest Domestic Trade Is a Major Impediment to Their Conservation

20 BirdingASIA 27 (2017): 20–25 CONSERVATION ALERT Records of four Critically Endangered songbirds in the markets of Java suggest domestic trade is a major impediment to their conservation VINCENT NIJMAN, SUCI LISTINA SARI, PENTHAI SIRIWAT, MARIE SIGAUD & K. ANNEISOLA NEKARIS Introduction 1.2 million wild-caught birds (the vast majority Bird-keeping is a popular pastime in Indonesia, and of them songbirds) were sold in the Java and Bali nowhere more so than amongst the people of Java. markets each year. Taking a different approach, It has deep cultural roots, and traditionally a kukilo Jepson & Ladle (2005) made use of a survey of (bird in the Javanese language) was one of the five randomly selected households in the Javan cities things a Javanese man should pursue or obtain in of Jakarta, Bandung, Semarang and Surabaya, order to live a fulfilling life (the others being garwo, and Medan in Sumatra, which together make up a wife, curigo, a Javanese dagger, wismo, a house or a quarter of the urban Indonesian population, to a place to live, and turonggo, a horse, as a means estimate that between 600,000 and 760,000 wild- of transportation). A kukilo represents having a caught native songbirds were acquired each year. hobby, and it often takes the form of owning a Extrapolating this to the urban population of Java, perkutut (Zebra Dove Geopelia striata) or a kutilang which amounts to 60% of Indonesia’s total, it (Sooty-headed Bulbul Pycnonotus aurigaster) but suggests that a total of 1.4–1.8 million wild-caught also a wide range of other birds (Nash 1993, Chng native songbirds were acquired. -

Illegal Trade Pushing the Critically Endangered Black-Winged Myna Acridotheres Melanopterus Towards Imminent Extinction

Bird Conservation International, page 1 of 7 . © BirdLife International, 2015 doi:10.1017/S0959270915000106 Short Communication Illegal trade pushing the Critically Endangered Black-winged Myna Acridotheres melanopterus towards imminent extinction CHRIS R. SHEPHERD , VINCENT NIJMAN , KANITHA KRISHNASAMY , JAMES A. EATON and SERENE C. L. CHNG Summary The Critically Endangered Black-winged Myna Acridotheres melanopterus is being pushed towards the brink of extinction in Indonesia due to continued demand for it as a cage bird and the lack of enforcement of national laws set in place to protect it. The trade in this species is largely to supply domestic demand, although an unknown level of international demand also persists. We conducted five surveys of three of Indonesia’s largest open bird markets (Pramuka, Barito and Jatinegara), all of which are located in the capital Jakarta, between July 2010 and July 2014. No Black-winged Mynas were observed in Jatinegara, singles or pairs were observed during every survey in Barito, whereas up to 14 birds at a time were present at Pramuka. The average number of birds observed per survey is about a quarter of what it was in the 1990s when, on average, some 30 Black-winged Mynas were present at Pramuka and Barito markets. Current asking prices in Jakarta are high, with unbartered quotes averaging USD 220 per bird. Our surveys of the markets in Jakarta illustrate an ongoing and open trade. Dealers blatantly ignore national legislation and are fearless of enforcement actions. Commercial captive breeding is unlikely to remove pressure from remaining wild populations of Black-winged Mynas. Efforts to end the illegal trade in this species and to allow wild populations to recover are urgently needed. -

Pica (Pica) Bottanensis in India

PRŷS-JONES & RASMUSSEN: Black-rumped Magpie 71 The status of the Black-rumped Magpie Pica (pica) bottanensis in India Robert P. Prŷs-Jones & Pamela C. Rasmussen Prŷs-Jones, R. P., & Rasmussen, P. C., 2018. The status of the Black-rumped Magpie Pica (pica) bottanensis in India. Indian BIRDS 14 (3): 71–73. Robert P. Prŷs-Jones, Bird Group, Department of Life Sciences, Natural History Museum, Akeman St, Tring, Herts HP23 6AP, UK. E-mail: [email protected] [RPP-J] Pamela C. Rasmussen, Department of Integrative Biology and MSU Museum, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48864, USA; Bird Group, Department of Life Sciences, Natural History Museum, Akeman St, Tring, Herts HP23 6AP, UK. E-mail: [email protected] [PCR] Manuscript received on 01 February 2018. he presence of the Eurasian Magpie Pica pica (sensu lato) in India (Praveen within Native Sikkim, any such records having et al. 2016) is predominantly based on the well-documented occurrence of more probably been a mistake for southern Tthe race bactriana in the north-western Himalayas east to northern Himachal Tibet,” (Meinertzhagen 1927: 371). There is Pradesh (Rasmussen & Anderton 2012; Dickinson & Christidis 2014). However, thus a clear contradiction between his own the question as to whether the taxon bottanensis may additionally occur, or have writings and the existence of his specimen, occurred, in Sikkim has recently resurfaced as a result of a comprehensive molecular from which we deduce that he most likely phylogenetic study of the genus Pica by Song et al. (2018), who recognised Pica (p.) stole the specimen later, relabelling it without bottanensis to be an anciently diverged and distinctive lineage. -

Magnificent Magpie Colours by Feathers with Layers of Hollow Melanosomes Doekele G

© 2018. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Experimental Biology (2018) 221, jeb174656. doi:10.1242/jeb.174656 RESEARCH ARTICLE Magnificent magpie colours by feathers with layers of hollow melanosomes Doekele G. Stavenga1,*, Hein L. Leertouwer1 and Bodo D. Wilts2 ABSTRACT absorption coefficient throughout the visible wavelength range, The blue secondary and purple-to-green tail feathers of magpies are resulting in a higher refractive index (RI) than that of the structurally coloured owing to stacks of hollow, air-containing surrounding keratin. By arranging melanosomes in the feather melanosomes embedded in the keratin matrix of the barbules. barbules in more or less regular patterns with nanosized dimensions, We investigated the spectral and spatial reflection characteristics of vivid iridescent colours are created due to constructive interference the feathers by applying (micro)spectrophotometry and imaging in a restricted wavelength range (Durrer, 1977; Prum, 2006). scatterometry. To interpret the spectral data, we performed optical The melanosomes come in many different shapes and forms, and modelling, applying the finite-difference time domain (FDTD) method their spatial arrangement is similarly diverse (Prum, 2006). This has as well as an effective media approach, treating the melanosome been shown in impressive detail by Durrer (1977), who performed stacks as multi-layers with effective refractive indices dependent on extensive transmission electron microscopy of the feather barbules the component media. The differently coloured magpie feathers are of numerous bird species. He interpreted the observed structural realised by adjusting the melanosome size, with the diameter of the colours to be created by regularly ordered melanosome stacks acting melanosomes as well as their hollowness being the most sensitive as optical multi-layers. -

Borneo Im September 2015 D. Rudolf

ALBATROS-TOURS ORNITHOLOGISCHE STUDIENREISEN Jürgen Schneider Altengassweg 13 - 64625 Bensheim - Tel.: +49 (0) 62 51 22 94 - Fax: +49 (0) 62 51 64 457 E-Mail: [email protected] - Homepage: www.albatros-tours.com Borneo Provinz Sabah vom 09.-24. September 2015 Bericht und Fotos von Krystyna und Dr. Dieter Rudolf Reisebericht Borneo 1 ALBATROS-TOURS Unsere Gruppe Krystyna Rudolf, Sophoan Sanh (Reiseleitung), Dr. Dieter Rudolf (v.l.n.r.) Reisebericht Borneo 3 ALBATROS-TOURS Borneo Provinz Sabah 09.-24. September 2015 Bericht und Fotos von Krystyna und Dr. Dieter Rudolf Veranstalter: Albatros Tours und Sophoan Sanh Teilnehmer: Krystyna Rudolf Dieter Rudolf Sophoan Sanh (englischsprachige touristische und ornithologische Reiseleitung) 1. Gesamteindruck Eine unserer schönsten Reisen mit Albatros Tours. Dies ist vor allem Sophoan Sanh zu danken, die die Reise touristisch organisiert und ornithologisch durchgeführt hat. Mit ihrer herzlichen Art hat sie sofort unsere Herzen erobert. Unterbringung und Verpflegung waren sorgfältig ausgewählt, die Tagesabläufe gut geplant. Notwendige Anpassungen an die physischen Möglichkeiten der immerhin älteren Teilnehmer und an die örtlichen Gegebenheiten wurden von Sophoan umsichtig und geräuschlos vorgenommen. Das Essen war sehr gut, ortstypisch, schmackhaft und verträglich. Die Früchte der Saison wurden probiert. Sophoan hat sie immer wieder auf den lokalen Märkten gekauft und herbeigeschleppt. Die abendliche Diskussion der Beobachtungsliste war stets mit der Übergabe der Ziel- Arten für den nächsten Tag verbunden. Wir konnten uns also noch einmal darauf vorbereiten, wonach am nächsten Beobachtungsort Ausschau zu halten war. Sophoan hat in jahrelanger praktischer Tätigkeit ein umfangreiches ornithologisches Wissen und Beobachtungstaktik aufgebaut. Ihre Kenntnisse der Vogelstimmen sind exzellent. Sie bringt eine umfassende Stimmensammlung zum Einsatz, was die Voraussetzung dafür war, dass sich manche Vögel überhaupt zeigten.