Gibbon Journal Nr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Description of a New Species of Hoolock Gibbon (Primates: Hylobatidae) Based

1 Title: Description of a new species of Hoolock gibbon (Primates: Hylobatidae) based 2 on integrative taxonomy 3 Peng-Fei Fan1,2#,*, Kai He3,4,#, *, Xing Chen3,#, Alejandra Ortiz5,6,7, Bin Zhang3, Chao 4 Zhao8, Yun-Qiao Li9, Hai-Bo Zhang10, Clare Kimock5,6, Wen-Zhi Wang3, Colin 5 Groves11, Samuel T. Turvey12, Christian Roos13, Kris M. Helgen4, Xue-Long Jiang3* 6 7 8 9 1. School of Life Sciences, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, 510275, P.R. China 10 2. Institute of Eastern-Himalaya Biodiversity Research, Dali University, Dali, 671003, 11 P.R. China 12 3. Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, 650223, 13 P.R. China 14 4. Department of Vertebrate Zoology, National Museum of Natural History, 15 Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., 20013, USA 16 5. Center for the Study of Human Origins, Department of Anthropology, New York 17 University, New York, 10003, USA 18 6. New York Consortium in Evolutionary Primatology (NYCEP), New York, 10024, 19 USA 20 7. Institute of Human Origins, School of Human Evolution and Social Change, 21 Arizona State University, Tempe, 85281, USA. 22 8. Cloud Mountain Conservation, Dali, 671003, P.R. China 1 23 9. Kunming Zoo, Kunming, 650021, P. R. China 24 10. Beijing Zoo, Beijing, 100044, P.R. China 25 11. School of Archaeology & Anthropology, Australian National University, Acton, 26 ACT 2601, Australia 27 12. Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, NW1 4RY, London, UK 28 13. Gene Bank of Primates and Primate Genetics Laboratory, German Primate Center, 29 Leibniz Institute for Primate Research, Kellnerweg 4, 37077 Göttingen, Germany 30 31 32 Short title: A new species of small ape 33 #: These authors contributed equally to this work. -

10 Sota3 Chapter 7 REV11

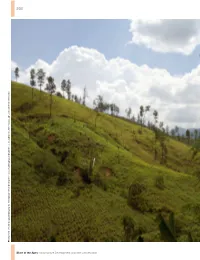

200 Until recently, quantifying rates of tropical forest destruction was challenging and laborious. © Jabruson 2017 (www.jabruson.photoshelter.com) forest quantifying rates of tropical Until recently, Photo: State of the Apes Infrastructure Development and Ape Conservation 201 CHAPTER 7 Mapping Change in Ape Habitats: Forest Status, Loss, Protection and Future Risk Introduction This chapter examines the status of forested habitats used by apes, charismatic species that are almost exclusively forest-dependent. With one exception, the eastern hoolock, all ape species and their subspecies are classi- fied as endangered or critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) (IUCN, 2016c). Since apes require access to forested or wooded land- scapes, habitat loss represents a major cause of population decline, as does hunting in these settings (Geissmann, 2007; Hickey et al., 2013; Plumptre et al., 2016b; Stokes et al., 2010; Wich et al., 2008). Until recently, quantifying rates of trop- ical forest destruction was challenging and laborious, requiring advanced technical Chapter 7 Status of Apes 202 skills and the analysis of hundreds of satel- for all ape subspecies (Geissmann, 2007; lite images at a time (Gaveau, Wandono Tranquilli et al., 2012; Wich et al., 2008). and Setiabudi, 2007; LaPorte et al., 2007). In addition, the chapter projects future A new platform, Global Forest Watch habitat loss rates for each subspecies and (GFW), has revolutionized the use of satel- uses these results as one measure of threat lite imagery, enabling the first in-depth to their long-term survival. GFW’s new analysis of changes in forest availability in online forest monitoring and alert system, the ranges of 22 great ape and gibbon spe- entitled Global Land Analysis and Dis- cies, totaling 38 subspecies (GFW, 2014; covery (GLAD) alerts, combines cutting- Hansen et al., 2013; IUCN, 2016c; Max Planck edge algorithms, satellite technology and Insti tute, n.d.-b). -

Bird Species Richness Along an Elevational Gradient in a Forest At

Zoological Studies 51(3): 362-371 (2012) Bird Species Richness along an Elevational Gradient in a Forest at Jianfengling, Hainan Island, China Fa-Sheng Zou1,2,3,*, Gui-Zhu Chen3, Qiong-Fang Yang1,2, and Yi-De Li4 1Guangdong Entomological Institute, Guangzhou 510260, China 2South China Institute of Endangered Animals, Guangzhou 510260, China 3School of Environmental Science and Engineering, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou 510275, China 4Research Institute of Tropical Forestry, Chinese Academy of Forestry, Guangzhou 510520, China (Accepted November 14, 2011) Fa-Sheng Zou, Gui-Zhu Chen, Qiong-Fang Yang, and Yi-De Li (2012) Bird species richness along an elevational gradient in a forest at Jianfengling, Hainan Island, China. Zoological Studies 51(3): 362-371. The avian communities of Hainan I., China are poorly known and under considerable threat. In our studies at Jianfengling, Hainan I. between May 2000 and Sept. 2004, 117 bird species were recorded using fixed-radius point counts and mist-netting at 3 elevations (200, 500, and 1000 m). Numbers of bird species recorded at the 3 elevations were 67 (200 m), 67 (500 m), and 89 (1000 m), of which 15 species were recorded exclusively at 200 m, 11 at 500 m, and 24 at 1000 m. The highest bird species richness occurred at the highest elevation (1000 m). The pattern of bird species richness differed from those of continental China and the island of Taiwan. Each elevation hosted a unique assemblage of special conservation concern. Species which require mature, full-canopy forest, and are often associated with mixed-species flocks were mainly distributed at 1000 m. -

Gibbon Classification : the Issue of Species and Subspecies

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1988 Gibbon classification : the issue of species and subspecies Erin Lee Osterud Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Biological and Physical Anthropology Commons, and the Genetics and Genomics Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Osterud, Erin Lee, "Gibbon classification : the issue of species and subspecies" (1988). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3925. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.5809 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Erin Lee Osterud for the Master of Arts in Anthropology presented July 18, 1988. Title: Gibbon Classification: The Issue of Species and Subspecies. APPROVED BY MEM~ OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: Marc R. Feldesman, Chairman Gibbon classification at the species and subspecies levels has been hotly debated for the last 200 years. This thesis explores the reasons for this debate. Authorities agree that siamang, concolor, kloss and hoolock are species, while there is complete lack of agreement on lar, agile, moloch, Mueller's and pileated. The disagreement results from the use and emphasis of different character traits, and from debate on the occurrence and importance of gene flow. GIBBON CLASSIFICATION: THE ISSUE OF SPECIES AND SUBSPECIES by ERIN LEE OSTERUD A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in ANTHROPOLOGY Portland State University 1989 TO THE OFFICE OF GRADUATE STUDIES: The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Erin Lee Osterud presented July 18, 1988. -

Munnar Hills Kite Flying Hazards Ashy Woodswallow | Vol

VOL. 10 NO. 1 Munnar Hills Kite flying hazards Ashy Woodswallow | Vol. 10 No. 1 10 | Vol. RDS I B Indian Indian BIRDS www.indianbirds.in VOL. 10 NO. 1 DATE OF PUBLICATION: 30 APRIL 2015 ISSN 0973-1407 EDITOR: Aasheesh Pittie Contents [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITORS: V. Santharam, Praveen J. EDITORIAL BOARD Maan Barua, Anwaruddin Choudhury 1 Bird diversity of protected areas in the Munnar Hills, Kerala, Bill Harvey, Farah Ishtiaq, Rajah Jayapal India Madhusudan Katti, R. Suresh Kumar Praveen J. & Nameer P. O. Taej Mundkur, Rishad Naoroji, Prasad Ganpule Suhel Quader, Harkirat Singh Sangha, C. Sashikumar, Manoj Sharma, S. Subramanya, 13 Kite flying: Effect ofChinese manja on birds in Bangalore, India K. S. Gopi Sundar Sharat Babu, S. Subramanya & Mohammed Dilawar CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Ragupathy Kannan, Lavkumar Khachar (1931-2015) 19 Some notes on the breeding of Ashy Woodswallow CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS Artamus fuscus in Gujarat, India Clement Francis, Ramki Sreenivasan Raju Vyas & Kartik Upadhyay LAYOUT & COVER DESIGN: K. Jayaram OffICE: P. Rambabu 23 A record of Sooty Tern Onychoprion fuscatus from Gujarat, India NEW ORNIS FOUNDATION M. U. Jat & B. M. Parasharya Registration No. 314/2004 Sighting of the Eurasian Bittern Botaurus stellaris at Amravati, FOUNDER TRUSTEES 24 Zafar Futehally (1920–2013) Maharashtra, India Aasheesh Pittie, V. Santharam Rahul Gupta TRUSTEES Aasheesh Pittie, V. Santharam, Rishad Naoroji, A Great Spotted Woodpecker Dendrocopos major in Nagaland Taej Mundkur, S. Subramanya, 25 Suhel Quader, Praveen J. Jainy Kuriakose, Dileep Kumar V. P., Chewang R. Bonpo & Peter Lobo AIMS & OBJECTIVES • To publish a newsletter that will provide a platform to birdwatchers for publishing notes and observations Sighting of Short-tailed Shearwater Ardenna tenuirostris, and primarily on birds of South Asia. -

Nomascus Hainanus) We Conducted a Long-Term Dietary Composition Survey in Bawangling National Nature Reserve, Hainan Island, China from 2002 to 2014

NORTH-WESTERN JOURNAL OF ZOOLOGY 14 (2): 213-219 ©NWJZ, Oradea, Romania, 2018 Article No.: e171703 http://biozoojournals.ro/nwjz/index.html Thirteen years observation on diet composition of Hainan gibbons (Nomascushainanus) Huaiqing DENG and Jiang ZHOU* School of Life Sciences, Guizhou Normal University, Guiyang, Guizhou, 550001, China E-mail: [email protected] *Corresponding author, J. Zhou, Tel:+8613985463226, E-mail: [email protected] Received: 08. April 2017 / Accepted: 27. July 2017 / Available online: 27. July 2017 / Printed: December 2018 Abstract. Researches on diets and feeding behavior of endangered species are critical to understand ecological adaptations and develop conservation strategies. To document the diet of the Hainan gibbon (Nomascus hainanus) we conducted a long-term dietary composition survey in Bawangling National Nature Reserve, Hainan Island, China from 2002 to 2014. Transects and quadrants were established to monitor plant phenology and to count tree species. Tracking survey and scan-sampling method were used to record the feeding species and feeding time of Hainan Gibbon. Our results showed that Hainan gibbons’ habitat vegetation structure is tropical montane evergreen forest dominated by Lauraceae species while Dipterocarpaceae, Leguminosae and Ficusare rare. Hainan gibbons consume 133 plant species across 83 genera and 51 families. Hainan gibbons consumed more Lauraceae and Myrtaceae plant species than other plant species, whereas their consumption of leguminous species was little and with no Dipterocarpaceae compared to other gibbons. Furthermore, we classified the food plants as different feeding parts and confirmed that this gibbon species is a main fruits eater particularly during the wet season (114 species,64.8% feeding time), meanwhile we also observed five species of animal foods. -

Thailand Highlights 14Th to 26Th November 2019 (13 Days)

Thailand Highlights 14th to 26th November 2019 (13 days) Trip Report Siamese Fireback by Forrest Rowland Trip report compiled by Tour Leader: Forrest Rowland Trip Report – RBL Thailand - Highlights 2019 2 Tour Summary Thailand has been known as a top tourist destination for quite some time. Foreigners and Ex-pats flock there for the beautiful scenery, great infrastructure, and delicious cuisine among other cultural aspects. For birders, it has recently caught up to big names like Borneo and Malaysia, in terms of respect for the avian delights it holds for visitors. Our twelve-day Highlights Tour to Thailand set out to sample a bit of the best of every major habitat type in the country, with a slight focus on the lush montane forests that hold most of the country’s specialty bird species. The tour began in Bangkok, a bustling metropolis of winding narrow roads, flyovers, towering apartment buildings, and seemingly endless people. Despite the density and throng of humanity, many of the participants on the tour were able to enjoy a Crested Goshawk flight by Forrest Rowland lovely day’s visit to the Grand Palace and historic center of Bangkok, including a fun boat ride passing by several temples. A few early arrivals also had time to bird some of the urban park settings, even picking up a species or two we did not see on the Main Tour. For most, the tour began in earnest on November 15th, with our day tour of the salt pans, mudflats, wetlands, and mangroves of the famed Pak Thale Shore bird Project, and Laem Phak Bia mangroves. -

Avifaunal Diversity of Bibhutibhushan Wildlife Sanctuary, West Bengal, India

Available online at www.worldscientificnews.com WSN 71 (2017) 150-167 EISSN 2392-2192 Avifaunal Diversity of Bibhutibhushan Wildlife Sanctuary, West Bengal, India Shiladitya Mukhopadhyay1,* and Subhendu Mazumdar2 1Post Graduate Department of Zoology, Barasat Government College, North 24 Parganas, India 2Department of Zoology, Shibpur Dinobundhoo Institution (College), Shibpur, Howrah, India *E-mail address: [email protected] ABSTRACT Birds are found in a variety of habitats, performing various functions. They are highly sensitive to even minor perturbation in ecosystems. Documentation of avian assemblages in different ecosystems is, therefore, becoming increasingly important from environmental monitoring perspective. In absence of comprehensive account of birds of Bibhutibhushan Wildlife Sanctuary, West Bengal, India, we made an attempt to document the birds thriving in this protected area. A total of 102 species of birds belonging to 13 orders and 46 families were recorded during the study period (June 2013 – May 2016). Maximum number of species belong to the order Passeriformes (49 species) and minimum under order Anseriformes (1 species). Among the total bird species, 83 species (81.37%) were resident, 15 species (14.71%) were winter visitor, three species (2.94%) were summer visitor and one species (0.98%) was passage migrant. We noted 38 species of birds (including 36 residents and two summer visitors) to breed within the sanctuary. Analysis of feeding guild data revealed that 46.08% were insectivore, 22.55% were carnivore, 15.69% were omnivore, 6.86% were granivore, 5.88% were frugivore, 1.96% were nectarivore and 0.98% were herbivore. Grey-headed Fish Eagle (Icthyophaga ichthyaetus) and Red- breasted Parakeet (Psittacula alexandri) are two Near Threatened (NT) species designated by IUCN. -

Distribution and Conservation Status of the Vulnerable Eastern Hoolock

Distribution and conservation status of the Vulnerable eastern hoolock gibbon Hoolock leuconedys in China F an P eng-Fei,Xiao W en,Huo S heng,Ai H uai-Sen,Wang T ian-Can and L in R u-Tao Abstract We conducted an intensive survey of the Vul- Several recent studies have described the eastern hoolock nerable eastern hoolock gibbon Hoolock leuconedys along gibbon populations outside China. Das et al. (2006)identi- the west bank of the Salween River in southern China, fied the eastern species for the first time in the Lohit district covering all known hoolock gibbon populations in China. of Arunachal Pradesh in India. Chetry et al. (2008) found an We found 40–43 groups, with a mean group size of 3.9, additional 150 groups between Dibang and Lohit in Aruna- and five solitary individuals. We estimated the total chal Pradesh, India. Brockelman et al. (2009) estimated the population to be , 200. In the nine groups for which we population size in Mahamyaing Wildlife Sanctuary in recorded composition, seven comprised one adult pair and Myanmar to be c. 5,900.Walkeretal.(2009) estimated that 0–3 offspring and the other two groups both comprised the Hukaung Valley Reserve in northern Myanmar could one adult male and two adult females. The population is support tens of thousands of eastern hoolock gibbons, severely fragmented, in 17 locations, with the largest sub- potentially the largest population in the world. population containing only five family groups. Compared No recent data are available on the current distribution, with the population in 1985 and 1994 five subpopulations status and population size of H. -

Ranging Behavior of Eastern Hoolock Gibbon (Hoolock Leuconedys) in a Northern Montane Forest in Gaoligongshan, Yunnan, China

Primates (2014) 55:239–247 DOI 10.1007/s10329-013-0394-y ORIGINAL ARTICLE Ranging behavior of eastern hoolock gibbon (Hoolock leuconedys) in a northern montane forest in Gaoligongshan, Yunnan, China Dao Zhang • Han-Lan Fei • Sheng-Dong Yuan • Wen-Mo Sun • Qing-Yong Ni • Liang-Wei Cui • Peng-Fei Fan Received: 17 December 2012 / Accepted: 17 October 2013 / Published online: 13 November 2013 Ó Japan Monkey Centre and Springer Japan 2013 Abstract Generally, food abundance and distribution was patchily distributed within their total (14-month) home exert important influence on primate ranging behavior. range, and during most months they used only a small portion Hoolock gibbons (genus Hoolock) live in lowland and of their total home range. In order to find enough food, the montane forests in India, Bangladesh, Myanmar and China. group shifted its monthly home range according to the sea- All information about hoolock gibbons comes from studies sonal availability of food species. To satisfy their annual on western hoolock gibbons (Hoolock hoolock) living in food requirements, they occupied a total home range of lowland forest. Between August 2010 and September 2011, 93 ha. The absence of neighboring groups of gibbons and the we studied the ranging behavior of one habituated group of presence of tsaoko cardamom (Amomum tsaoko) plantations eastern hoolock gibbon (H. leuconedys) living in a seasonal may also have influenced the ranging behavior of the group. montane forest in Gaoligongshan, Yunnan, China. Results Further long-term studies of neighboring groups living in show that the study group did not increase foraging effort, intact forests are required to assess these effects. -

Bird Checklists of the World Country Or Region: Ghana

Avibase Page 1of 24 Col Location Date Start time Duration Distance Avibase - Bird Checklists of the World 1 Country or region: Ghana 2 Number of species: 773 3 Number of endemics: 0 4 Number of breeding endemics: 0 5 Number of globally threatened species: 26 6 Number of extinct species: 0 7 Number of introduced species: 1 8 Date last reviewed: 2019-11-10 9 10 Recommended citation: Lepage, D. 2021. Checklist of the birds of Ghana. Avibase, the world bird database. Retrieved from .https://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/checklist.jsp?lang=EN®ion=gh [26/09/2021]. Make your observations count! Submit your data to ebird. -

Sound Spectrum Characteristics of Eastern Black Crested Gibbons

NORTH-WESTERN JOURNAL OF ZOOLOGY 13 (2): 347-351 ©NwjZ, Oradea, Romania, 2017 Article No.: e161705 http://biozoojournals.ro/nwjz/index.html Sound spectrum characteristics of Eastern Black Crested Gibbons Huaiqing DENG#, Huamei WEN# and Jiang ZHOU* School of Life Sciences, Guizhou Normal University, Guiyang, Guizhou, 550001, China, E-mail: [email protected] # These authors contributed to the work equally and regarded as Co-first authors. * Corresponding author, J. Zhou, E-mail: [email protected], Tel.:13985463226 Received: 01. November 2016 / Accepted: 07. September 2016 / Available online: 19. September 2016 / Printed: December 2017 Abstract. Studies about the sound spectrum characteristics and the intergroup differences in eastern black crested gibbon (Nomascus nasutus) song are still rare. Here, we studied the singing behavior of eastern black crested gibbon based on song samples of three groups of gibbons collected from Trung Khanh, northern Vietnam. The results show that: 1) Song frequency of both adult male and adult female eastern black crested gibbon is low and both are below 2 KHz; 2) Songs of adult male eastern black gibbons are composed mainly of short syllables (aa notes) and frequency modulated syllables (FM notes), while adult female gibbons only produce a stable and stereotyped pattern of great calls; 3) There is significant differences among the three groups in highest and lowest frequency of FM syllable in males’ song; 4) The song chorus is dominated by adult males, while females add a great call; 5) The sound spectrum frequency is lower and complex, which is different from Hainan gibbon. The low frequency in the singing of the eastern black crested gibbon is related to the structure and low quality of the vegetation of its habitat.