Historical Precedents for Martha Stewart

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Save the World, Eat Insects | Martha Stewart Living

August 14, 2017 To Save the World, Eat Insects Why this Texas company thinks crickets are the future of food. By Bridget Shirvell 125 MORE S H A RE S PHOTOGRAPHY BY: COURTESY OF ASPIRE Find a bowl of slightly roasted crickets as part of the spread at your friend's backyard barbecue and chances are you'll be looking for a new squad. "There's an ick factor, that's people's first impression," said Vincent Vitale, business development manager of Aspire Food Group. Aspire, which is said to be the world's first fully automated cricket farm, is betting on people getting over the ick factor. Based in Texas, the company farms and produces a variety of edible cricket products, sold through its Aketta line. Think cricket protein flour, paleo granola and cricket protein snacks, such as whole roasted crickets and flavored roasted crickets. (Make Your Own Granola -- Whether You Add Cricket Powder is Up to You) PHOTOGRAPHY BY: COURTESY OF ASPIRE This is what an automated cricket farm looks like. WHAT CRICKETS TASTE LIKE Crickets -- I'm taking Vincent's word here -- have a slight sunflower seed-like taste, with a bit of earthy nuttiness and are crispy like chips. WHY THE WORLD NEEDS CRICKETS There's long history of crickets and other insects staring in dishes from cuisines around the globe. Nearly two billion people regularly eat insects, and the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization would like even more people to give them a shot. That's because insects are an incredible source of protein, 30 grams of crickets is about 20 grams of protein, compared to beef with 8 grams of protein, and farming them is much more sustainable than producing beef, poultry and fish. -

Magazine Collection

Magazine Collection American Craft Earth Magazine Interweave Knits American Patchwork and Quilting Eating Well iPhone Life American PHOTO Elle Islands American Spectator Elle DÉCOR Kiplinger’s Personal Finance AppleMagazine Equs La Cucina Italiana US Architectural Record ESPN The Magazine Ladies Home Journal Astronomy Esquire Living the Country Life Audubon Esquire UK Macworld Backcountry Magazine Every Day with Rachel Ray Marie Claire Backpacker Everyday Food Martha Stewart Living Baseball America Family Circle Martha Stewart Weddings Bead Style Family Handyman Maxim Bicycle Times FIDO Friendly Men’s Fitness Bicycling Field & Stream Men’s Health Bike Fit Pregnancy Mental Floss Bloomberg Businessweek Food Network Magazine Model Railroader Bloomberg Businessweek-Europe Forbes Mother Earth News Boating Garden Design Mother Jones British GQ Gardening & Outdoor Living Motor Trend Canoe & Kayak Girls’ Life Motorcyclist Car and Driver Gluten-Free Living National Geographic Clean Eating Golf Tips National Geographic Traveler Climbing Good Housekeeping Natural Health Cloth Paper Scissors GreenSource New York Review of Books Cosmopolitan Newsweek Grit Cosmopolitan en Espanol O the Oprah Magazine Guideposts Country Living OK Magazine Guitar Player Cruising World Organic Gardening Harper’s Bazaar Cycle World Outdoor Life Harvard Business Review Diabetic Living Outdoor Photographer HELLO! Magazine Digital Photo Outside Horse & Rider Discover Oxygen House Beautiful Dressage Today Parenting Interweave Crochet HARFORD COUNTY PUBLIC LIBRARY Magazine -

ADOPTED SEP 0 7 2010 SECONDED BY: C.R~ LOS ANGELES CITY Council

CITY OF LOS ANGELES RESOLUTION MARC MARMARO WHEREAS, Marc Marmaro was born on February 26, 1948, in the Bronx, New York; and, WHEREAS, Marmaro went on to receive a B.A. from George Washington University in 1969 and J.D. cum laude, Order of the Coif, from New York University School of Law in 1972; and, WHEREAS, in 1972, Marmaro clerked for the Honorable John J. Gibbons, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit; and, WHEREAS, Marmaro served the U.S. Attorney's Office, Southern District of New York as an assistant U.S. attorney from 1975 to 1978; and, WHEREAS, Marmaro moved to the City of Los Angeles to join Manatt, Phelps & Phillips as a litigation associate and partner until 1981; and, WHEREAS, in 1981, Marmaro helped found the law firm Jeffer, Mangels, Butler, & Marmaro, LLP, which has grown from 11 employees to over 140 in three cities across the United States; and, WHEREAS, Marmaro is a Fellow of the American College of Trial Lawyers; and, WHEREAS, in 2004, he was named California Lawyer of the Year in Intellectual Property by California Lawyer magazine for negotiating the settlement of spinal fusion technology patent disputes for $1.35 billion; and, WHEREAS, on June 30,2010, California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger appointed him to the Los Angeles County Superior Court; and, WHEREAS, on August 5, 2010, Marc Marmaro was officially sworn into office as a Judge for Los Angeles County Superior Court; and, NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED, that by the adoption of this resolution, the City Council of Los Angeles, the Mayor, and the City Attorney extends their congratulations to Marc Marmaro for his judicial appointment, outstanding achievements, and constant pursuit for justice. -

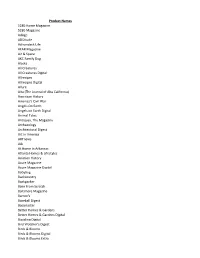

Product Names 5280 Home Magazine 5280 Magazine Adage Additude

Product Names 5280 Home Magazine 5280 Magazine AdAge ADDitude Adirondack Life AFAR Magazine Air & Space AKC Family Dog Alaska All Creatures All Creatures Digital Allrecipes Allrecipes Digital Allure Alta (The Journal of Alta California) American History America's Civil War Angels On Earth Angels on Earth Digital Animal Tales Antiques, The Magazine Archaeology Architectural Digest Art In America ARTnews Ask At Home In Arkansas Atlanta Homes & Lifestyles Aviation History Azure Magazine Azure Magazine Digital Babybug Backcountry Backpacker Bake From Scratch Baltimore Magazine Barron's Baseball Digest Bassmaster Better Homes & Gardens Better Homes & Gardens Digital Bicycling Digital Bird Watcher's Digest Birds & Blooms Birds & Blooms Digital Birds & Blooms Extra Blue Ridge Country Blue Ridge Motorcycling Magazine Boating Boating Digital Bon Appetit Boston Magazine Bowhunter Bowhunting Boys' Life Bridal Guide Buddhadharma Buffalo Spree BYOU Digital Car and Driver Car and Driver Digital Catster Magazine Charisma Chicago Magazine Chickadee Chirp Christian Retailing Christianity Today Civil War Monitor Civil War Times Classic Motorsports Clean Eating Clean Eating Digital Cleveland Magazine Click Magazine for Kids Cobblestone Colorado Homes & Lifestyles Consumer Reports Consumer Reports On Health Cook's Country Cook's Illustrated Coral Magazine Cosmopolitan Cosmopolitan Digital Cottage Journal, The Country Country Digital Country Extra Country Living Country Living Digital Country Sampler Country Woman Country Woman Digital Cowboys & Indians Creative -

Case Studies on the Downside of Transactional and Authoratitative Organizational Leadership Styles During Crisis Management

The Turkish Online Journal of Design, Art and Communication - TOJDAC ISSN: 2146-5193, October 2020 Volume 10 Issue 4, p.597-611 CASE STUDIES ON THE DOWNSIDE OF TRANSACTIONAL AND AUTHORATITATIVE ORGANIZATIONAL LEADERSHIP STYLES DURING CRISIS MANAGEMENT Vehbi GÖRGÜLÜ İstanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi, Türkiye [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6248-7289 ABSTRACT Leadership is a value gained through education and experience. Leadership communication has the potential make Corporate CommuniCations and risk management processes more dynamiC and efficient. From these aspeCts, leader Communication Can be very influential over sustainability of corporate success. The Current study aims to explore how authoritative and transaCtional leadership styles result with various Challenges during crisis communication and management. The crises experienced by The Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia, Toyota, FaCebook and the United Airlines companies are explored as case studies. The analysis is not limited with the Crisis proCesses, but also questions the efficiency of leadership models embraced by managers of these two organizations. Keywords: Leadership, Martha Stewart, United Airlines, Facebook, Crisis Management. OTORİTER VE SÜRDÜRÜMCÜ (TRANSAKSİYONEL) LİDERLİK YAKLAŞIMLARININ KRİZ YÖNETİMİ BAĞLAMINDAKİ KISITLILIKLARI ÜZERİNE VAKA İNCELEMELERİ ÖZ Liderlik doğuştan değil, eğitim ve deneyimle edinilen bir değer olarak kurumsal hayatta karşımıza çıkmaktadır. Etkili lider iletişimi, yalnızca kurumsal iletişim sürecini verimli kılmamakta, aynı zamanda kriz yönetim süreçlerinin de başarıyla sonuçlanmasını sağlamaktadır. Tüm bu yönleriyle, etkili lider iletişiminin şirketlerin geleceği üzerinde belirleyici olduğu vurgulanabilir. Mevcut çalışma, otoriter ve transaksiyonel liderlik modelleri ile kriz yönetim süreçleri arasındaki ilişkiyi inCelemektedir. Belirlenen ilişkinin inCelenebilmesi için seçilen vakalar The Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia Company, Toyota, FaCebook ve The United Airlines skandalları olmuştur. -

A Powerful Diversified Media & Marketing Company

A Powerful Diversified Media & Marketing Company Investor Day March 2, 2016 1 Disclaimer This presentation contains confidential information regarding Meredith Corporation (“Meredith” or the “Company”). This presentation constitutes “Business Information” under the Confidentiality Agreement the recipient signed and delivered to the Company and its use and retention are subject to the terms of such agreement. This presentation does not purport to contain all of the information that may be required to evaluate a potential transaction with the Company and any recipient hereof should conduct its own independent evaluation and due diligence investigation of the Company and the potential transaction. Nor shall this presentation be construed to indicate that there has been no change in the affairs of the Company since the date hereof or such other date as of which information is presented. Each recipient agrees that it will not copy, reproduce, disclose or distribute to others this presentation or the information contained herein, in whole or in part, at any time, without the prior written consent of the Company, except as expressly permitted in the Confidentiality Agreement. The recipient further agrees that it will cause its directors, officers, employees and representatives to use this presentation only for the purpose of evaluating its interest in a potential transaction with the Company and for no other purpose. Neither the Company nor any of its affiliates, employees or representatives makes any representation or warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy or completeness of any of the information contained in this presentation or any other information (whether communicated in written or oral form) transmitted or made available to the recipient, and each of such persons expressly disclaims any and all liability relating to or resulting from the use of this presentation. -

Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia (A)

For the exclusive use of E. Pepanyan, 2021. 9-501-080 REV: JULY 30, 2002 SUSAN FOURNIER, KERRY HERMAN, LAURA WINIG, ANDREA WOJNICKI Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia (A) Aretha Jackson, president of a private investment firm, put the phone down. It was Thursday, May 4, 2000. A client had scheduled the late evening call to ask her advice on investing in Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia (MSLO), an integrated content and media company dedicated to the business of homemaking. Jackson logged onto Yahoo.com to check MSLO’s stock performance. Noting the steady downward plunge since MSLO went public in October 1999, Jackson reminded herself that this was not an unusual post-IPO pattern. Maybe the old adage “buy low, sell high” might apply. But, what if the spiral signaled some fundamental problem? Jackson downloaded a copy of MSLO’s S-1 filing from July 29, 1999, and went to the “Risk Factors” section. One paragraph looked alarming, with the first sentence set off in caps: THE LOSS OF THE SERVICES OF MARTHA STEWART . WOULD MATERIALLY ADVERSELY AFFECT OUR BUSINESS. We are highly dependent upon our founder, chairman and chief executive officer, Martha Stewart. Martha Stewart’s talents, efforts, personality and leadership have been, and continue to be, critical to our success. The diminution or loss of the services of Martha Stewart, and any negative market or industry perception arising from that diminution or loss, would have a material adverse effect on our business. Martha Stewart remains the personification of our brands as well as our senior executive and primary creative force.1 Jackson read on. -

Stephens Spring Investment Conference June 3, 2015 Safe Harbor

Stephens Spring Investment Conference June 3, 2015 Safe Harbor This presentation and management’s public commentary contain certain forward-looking statements that are subject to risks and uncertainties. These statements are based on management’s current knowledge and estimates of factors affecting the Company and its operations. Statements in this presentation that are forward-looking include, but are not limited to, the statements regarding advertising revenues and investment spending, along with the Company’s revenue and earnings per share outlook. Actual results may differ materially from those currently anticipated. Factors that could adversely affect future results include, but are not limited to, downturns in national and/or local economies; a softening of the domestic advertising market; world, national, or local events that could disrupt broadcast television; increased consolidation among major advertisers or other events depressing the level of advertising spending; the unexpected loss or insolvency of one or more major clients or vendors; the integration of acquired businesses; changes in consumer reading, purchasing and/or television viewing patterns; increases in paper, postage, printing, syndicated programming or other costs; changes in television network affiliation agreements; technological developments affecting products or methods of distribution; changes in government regulations affecting the Company’s industries; increases in interest rates; and the consequences of any acquisitions and/or dispositions. The Company -

Meredith Secures Rights to License Martha Stewart Living Magazine and Marthastewart.Com

October 15, 2014 Meredith Secures Rights To License Martha Stewart Living Magazine And Marthastewart.com Meredith to also Assume Responsibility for Sales and Marketing of Martha Stewart Weddings Magazine and Marthastewartweddings.com Martha Stewart Editorial Team Will Continue to Create Award-Winning Content NEW YORK and DES MOINES, Iowa, Oct. 15, 2014 /PRNewswire/ -- Meredith Corporation (NYSE:MDP; www.meredith.com) today announced that it has entered into an agreement with Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia (NYSE: MSO) to acquire the rights to Martha Stewart Living and www.marthastewart.com pursuant to a 10-year licensing agreement. Under the terms of the agreement, Meredith will lead sales and marketing, circulation, production, and other non-editorial functions of Martha Stewart Living and Martha Stewart Weddings magazines. Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia's (MSLO) editorial team will continue to create its highly regarded content. Additionally, Meredith will assume responsibility for the sales and marketing of www.marthastewart.com and www.marthastewartweddings.com and its related assets, including its vast video library. The agreement, which applies to the United States and Canada, is effective November 1, 2014. Meredith will begin delivering editions starting with the February 2015 issue of Martha Stewart Living and the Winter 2014 special issue of Martha Stewart's Real Weddings. The agreement will not have a material effect on Meredith's fiscal 2015 second quarter financial performance, but will be accretive to Meredith's earnings for the second half of fiscal 2015 and in fiscal 2016. Meredith will provide more details on its fiscal 2015 first quarter earnings call on October 23, 2104. -

Fiscal 2020 Corporate Social Responsibility Report Fiscal 2020 Corporate Social Responsibility Report

Fiscal 2020 Corporate Social Responsibility Report Fiscal 2020 Corporate Social Responsibility Report Table of Contents Introduction | 3 • Letter from President and CEO Tom Harty • Mission Statement and Principles • Corporate Values and Guiding Principles Social | 5 • COVID-19 Response – Special Section • Volunteerism and Charitable Giving • Human Resources • Wellness • Diversity and Inclusion • Privacy Environment | 32 • Mission and Charter • Stakeholder Engagement • Responsible Paper • Waste and Recycling • Energy and Transportation • Water Conservation • Overall Environmental Initiatives Appendices | 59 2020 Corporate Social Responsibility Report | 2 INTRODUCTION Letter from Chairman and CEO Tom Harty Social Responsibility has always been important, but 2020 has elevated it to new levels. More than ever, corporations are expected to step up, whether it’s contributing to the elimination of social injustices that have plagued our country, keeping employees safe and healthy during the COVID-19 Pandemic, or fighting to curb global greenhouse gas emissions. Meredith has heard that call, and the many actions we are taking across the social responsibility spectrum are outlined in this report. We recognize the need for our business to be socially responsible, as well as a competitive and productive player in the marketplace. Just as we are devoted to providing our consumers with inspiration and valued content, we want them to feel great about the company behind the brands they love and trust. At Meredith, we promote the health and well-being of our employees; implement continuous improvements to make our operating systems, products and facilities more environmentally friendly; and take actions to create a just and inclusive environment for all. The social justice events of 2020 have brought diversity and inclusion to the forefront for many people both personally and professionally. -

Meredith Corporation Annual Report 2019

Meredith Corporation Annual Report 2019 Form 10-K (NYSE:MDP) Published: September 13th, 2019 PDF generated by stocklight.com UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended June 30, 2019 ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from __ to __ Commission file number 1-5128 MEREDITH CORPORATION (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Iowa 42-0410230 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 1716 Locust Des Moines, Iowa 50309-3023 Street, (Address of principal executive offices) (ZIP Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area (515) 284-3000 code: Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Trading Name of each exchange on which Title of each class Symbol registered Common Stock, par value $1 MDP New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: Title of class Class B Common Stock, par value $1 Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. x Yes o No Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. o Yes x No Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

MEREDITH CORPORATION Bear Stearns – 18Th Annual Media Conference March 1, 2005

MEREDITH CORPORATION Bear Stearns – 18th Annual Media Conference March 1, 2005 INTRODUCTION Next up will be Meredith Corp., [sic, Corporation] a diversified media company with magazine and broadcasting properties. Presenting will be President and COO Steve Lacy, Chief Financial Officer, Suku Radia, and Director of IR, Jim Jacobson. Before we get started, I need to tell you that Meredith is currently, or during the past 12 months, has been a noninvestment banking client of Bear Stearns, and Bear Stearns or one of its affiliates has received compensation from Meredith in the past 12 months. With that, Steve, please go on ahead. STEVE LACY Great. Thank you very much, Michael, and it’s certainly a pleasure to be here with you today. As Michael mentioned, to my right is Suku Radia, our Chief Financial Officer, and we’ll have a brief presentation for those of you who don’t know much about Meredith, and have really been asked to reserve most of the time for Q&A. So we’ll look forward to that as well. On the next slide is our little safe-harbor language, which I won’t go through, like Michael’s. Just to state that we will use some non-GAAP references during the discussion today, primarily EBITDA as it relates to our broadcasting business, and there are tables on our website that reconcile all the financial information. For those of you who might not be as familiar with the Meredith Corporation, we’ve really served the needs of the American household, American families now for 103 years, primarily through service journalism.