Sesbania Sesban) from the Republic of Chad: a Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trans-Boundary Forest Resources in West and Central Africa ______

Trans-boundary forest resources in West and Central Africa __________________________________________________________________________________ _ AFF / hamane Ma wanou r La Nigeria© of part southern the Sahelian in the in orest f rest o lands©AFF f k r y r a D P 2008 Secondary Trans-boundary forest resources in West and Central Africa Report (2018) i Trans-boundary forest resources in West and Central Africa __________________________________________________________________________________ _ TRANS-BOUNDARY FOREST RESOURCES IN WEST AND CENTRAL AFRICA Report (2018) Martin Nganje, PhD © African Forest Forum 2018. All rights reserved. African Forest Forum United Nations Avenue, Gigiri P.O. Box 30677-00100 Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254 20 722 4203 Fax: +254 20 722 4001 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.afforum.org ii Trans-boundary forest resources in West and Central Africa __________________________________________________________________________________ _ TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................................. v LIST OF TABLES .................................................................................................................. vi ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................... vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................... ix 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. -

Azorhizobium Doebereinerae Sp. Nov

ARTICLE IN PRESS Systematic and Applied Microbiology 29 (2006) 197–206 www.elsevier.de/syapm Azorhizobium doebereinerae sp. Nov. Microsymbiont of Sesbania virgata (Caz.) Pers.$ Fa´tima Maria de Souza Moreiraa,Ã, Leonardo Cruzb,Se´rgio Miana de Fariac, Terence Marshd, Esperanza Martı´nez-Romeroe,Fa´bio de Oliveira Pedrosab, Rosa Maria Pitardc, J. Peter W. Youngf aDepto. Cieˆncia do solo, Universidade Federal de Lavras, C.P. 3037 , 37 200–000, Lavras, MG, Brazil bUniversidade Federal do Parana´, C.P. 19046, 81513-990, PR, Brazil cEmbrapa Agrobiologia, antiga estrada Rio, Sa˜o Paulo km 47, 23 851-970, Serope´dica, RJ, Brazil dCenter for Microbial Ecology, Michigan State University, MI 48824, USA eCentro de Investigacio´n sobre Fijacio´n de Nitro´geno, Universidad Nacional Auto´noma de Mexico, Apdo Postal 565-A, Cuernavaca, Mor, Me´xico fDepartment of Biology, University of York, PO Box 373, York YO10 5YW, UK Received 18 August 2005 Abstract Thirty-four rhizobium strains were isolated from root nodules of the fast-growing woody native species Sesbania virgata in different regions of southeast Brazil (Minas Gerais and Rio de Janeiro States). These isolates had cultural characteristics on YMA quite similar to Azorhizobium caulinodans (alkalinization, scant extracellular polysaccharide production, fast or intermediate growth rate). They exhibited a high similarity of phenotypic and genotypic characteristics among themselves and to a lesser extent with A. caulinodans. DNA:DNA hybridization and 16SrRNA sequences support their inclusion in the genus Azorhizobium, but not in the species A. caulinodans. The name A. doebereinerae is proposed, with isolate UFLA1-100 ( ¼ BR5401, ¼ LMG9993 ¼ SEMIA 6401) as the type strain. -

Phytologia (June 2006) 88(1) the GENUS SENEGALIA

.. Phytologia (June 2006) 88(1) 38 THE GENUS SENEGALIA (FABACEAE: MIMOSOIDEAE) FROM THE NEW WORLD 1 2 3 David S. Seigler , John E. Ebinger , and Joseph T. Miller 1 Department of Plant Biology, University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois 61801, U.S.A. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Emeritus Professor of Botany, Eastern Illinois University, Charleston, Illinois 61920, U.S.A. E-mail: [email protected] 3 Joseph T. Miller, Roy J. Carver Center for Comparative Genomics, Department of Biological Sciences, 232 BB, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA 52242, U.S.A. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Morphological and genetic differences separating the subgenera of Acacia s.l. and molecular evidence that the genus Acacia s.l. is polyphyletic necessitate transfer of the following New World taxa from Acacia subgenus Aculeiferum Vassal to Senegalia, resulting in fifty-one new combinations in the genus Senegalia: Senegalia alemquerensis (Huber) Seigler & Ebinger, Senegalia altiscandens (Ducke) Seigler & Ebinger, Senegalia amazonica (Benth.) Seigler & Ebinger, Senegalia bahiensis (Benth.) Seigler & Ebinger, Senegalia bonariensis (Gillies ex Hook. & Arn.) Seigler & Ebinger, Senegalia catharinensis (Burkart) Seigler & Ebinger, Senegalia emilioana (Fortunato & Cialdella) Seigler & Ebinger, Senegalia etilis (Speg.) Seigler & Ebinger, Senegalia feddeana (Harms) Seigler & Ebinger, Senegalia fiebrigii (Hassl.) Seigler & Ebinger, Senegalia gilliesii (Steud.) Seigler & Ebinger, Senegalia grandistipula (Benth.) Seigler & Ebinger, Senegalia huberi (Ducke) Seigler & Ebinger, Senegalia kallunkiae (Grimes & Barneby) Seigler & Ebinger, Senegalia klugii (Standl. ex J. F. Macbr.) Seigler & Ebinger, Senegalia kuhlmannii (Ducke) Seigler & Ebinger, Senegalia lacerans (Benth.) Seigler & Ebinger, Senegalia langsdorfii (Benth.) Seigler & Ebinger, Senegalia lasophylla (Benth.) Seigler & Ebinger, Senegalia loretensis (J. F. Macbr.) Seigler & Ebinger, Senegalia macbridei (Britton & Rose ex J. -

Pacific Islands Area

Habitat Planting for Pollinators Pacific Islands Area November 2014 The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation www.xerces.org Acknowledgements This document is the result of collaboration with state and federal agencies and educational institutions. The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude for the technical assistance and time spent suggesting, advising, reviewing, and editing. In particular, we would like to thank the staff at the Hoolehua Plant Materials Center on the Hawaiian Island of Molokai, NRCS staff in Hawaii and American Samoa, and researchers and extension personnel at American Samoa Community College Land Grant (especially Mark Schmaedick). Authors Written by Jolie Goldenetz-Dollar (American Samoa Community College), Brianna Borders, Eric Lee- Mäder, and Mace Vaughan (The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation), and Gregory Koob, Kawika Duvauchelle, and Glenn Sakamoto (USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service). Editing and layout Ashley Minnerath (The Xerces Society). Updated November 2014 by Sara Morris, Emily Krafft, and Anne Stine (The Xerces Society). Photographs We thank the photographers who generously allowed use of their images. Copyright of all photographs remains with the photographers. Cover main: Jolie Goldenetz-Dollar, American Samoa Community College. Cover bottom left: John Kaia, Lahaina Photography. Cover bottom right: Gregory Koob, Hawaii Natural Resources Conservation Service. Funding This technical note was funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) and produced jointly by the NRCS and The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation. Additional support was provided by the National Institute for Food and Agriculture (USDA). Please contact Tony Ingersoll ([email protected]) for more information about this publication. -

Isolation and Characterization of Nitrogen Fixing Bacteria That Nodulate Alien Invasive Plant Species Prosopis Juliflora (Swart) DC

ISSN (E): 2349 – 1183 ISSN (P): 2349 – 9265 4(1): 183–191, 2017 DOI: 10.22271/tpr.201 7.v4.i1 .027 Research article Isolation and characterization of nitrogen fixing bacteria that nodulate alien invasive plant species Prosopis juliflora (Swart) DC. in Marigat, Kenya John O. Otieno1,2*, David W. Odee1, Stephen F. Omondi1, Charles Oduor1 and Oliver Kiplagat2 1Kenya Forestry Research Institute, P.O. Box 20412-00200, Nairobi, Kenya 2School of Agriculture and Biotechnology, University of Eldoret, P.O. Box 1125-30100, Eldoret, Kenya *Corresponding Author: [email protected] [Accepted: 22 April 2017] Abstract: A total of 150 bacterial strains were isolated from the root nodules of Prosopis juliflora growing in soils collected from Marigat area of Kenya. Soil samples from representative colonized zones of Tortilis, Grass and Prosopis were used in trapping the microsymbionts. A physiological plate screening allowed the selection of 60 strains which were characterized based on morphological, cultural and biochemical characteristics. Tolerance to salinity, acid and alkaline pH and resistance to antibiotics were studied as phenotypic markers. Morphological characteristics allowed the description of a wide physiological diversity among tested isolates. Establishing mutualistic interactions in novel environments is important for the successful establishment of some non-native plant species. The associations may have negative impact on the interaction networks of the native species whereby non-native species becoming dominant. Our study suggests that P. juliflora may have led to the diversity of N-fixing microsymbionts observed in the study area. The study provides basis for further research on the phylogeny of rhozobial strains nodulating P. juliflora, as well as their use as inoculants to improve growth and nitrogen fixation in arid lands of Kenya. -

Specificity in Legume-Rhizobia Symbioses

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Specificity in Legume-Rhizobia Symbioses Mitchell Andrews * and Morag E. Andrews Faculty of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Lincoln University, PO Box 84, Lincoln 7647, New Zealand; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +64-3-423-0692 Academic Editors: Peter M. Gresshoff and Brett Ferguson Received: 12 February 2017; Accepted: 21 March 2017; Published: 26 March 2017 Abstract: Most species in the Leguminosae (legume family) can fix atmospheric nitrogen (N2) via symbiotic bacteria (rhizobia) in root nodules. Here, the literature on legume-rhizobia symbioses in field soils was reviewed and genotypically characterised rhizobia related to the taxonomy of the legumes from which they were isolated. The Leguminosae was divided into three sub-families, the Caesalpinioideae, Mimosoideae and Papilionoideae. Bradyrhizobium spp. were the exclusive rhizobial symbionts of species in the Caesalpinioideae, but data are limited. Generally, a range of rhizobia genera nodulated legume species across the two Mimosoideae tribes Ingeae and Mimoseae, but Mimosa spp. show specificity towards Burkholderia in central and southern Brazil, Rhizobium/Ensifer in central Mexico and Cupriavidus in southern Uruguay. These specific symbioses are likely to be at least in part related to the relative occurrence of the potential symbionts in soils of the different regions. Generally, Papilionoideae species were promiscuous in relation to rhizobial symbionts, but specificity for rhizobial genus appears to hold at the tribe level for the Fabeae (Rhizobium), the genus level for Cytisus (Bradyrhizobium), Lupinus (Bradyrhizobium) and the New Zealand native Sophora spp. (Mesorhizobium) and species level for Cicer arietinum (Mesorhizobium), Listia bainesii (Methylobacterium) and Listia angolensis (Microvirga). -

Fort Ord Natural Reserve Plant List

UCSC Fort Ord Natural Reserve Plants Below is the most recently updated plant list for UCSC Fort Ord Natural Reserve. * non-native taxon ? presence in question Listed Species Information: CNPS Listed - as designated by the California Rare Plant Ranks (formerly known as CNPS Lists). More information at http://www.cnps.org/cnps/rareplants/ranking.php Cal IPC Listed - an inventory that categorizes exotic and invasive plants as High, Moderate, or Limited, reflecting the level of each species' negative ecological impact in California. More information at http://www.cal-ipc.org More information about Federal and State threatened and endangered species listings can be found at https://www.fws.gov/endangered/ (US) and http://www.dfg.ca.gov/wildlife/nongame/ t_e_spp/ (CA). FAMILY NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME LISTED Ferns AZOLLACEAE - Mosquito Fern American water fern, mosquito fern, Family Azolla filiculoides ? Mosquito fern, Pacific mosquitofern DENNSTAEDTIACEAE - Bracken Hairy brackenfern, Western bracken Family Pteridium aquilinum var. pubescens fern DRYOPTERIDACEAE - Shield or California wood fern, Coastal wood wood fern family Dryopteris arguta fern, Shield fern Common horsetail rush, Common horsetail, field horsetail, Field EQUISETACEAE - Horsetail Family Equisetum arvense horsetail Equisetum telmateia ssp. braunii Giant horse tail, Giant horsetail Pentagramma triangularis ssp. PTERIDACEAE - Brake Family triangularis Gold back fern Gymnosperms CUPRESSACEAE - Cypress Family Hesperocyparis macrocarpa Monterey cypress CNPS - 1B.2, Cal IPC -

The Journal of Phytopharmacology (Pharmacognosy and Phytomedicine Research) Phytopharmacology of Indian Plant Sesbania Grandiflora L

Suresh et. al. www.phytopharmajournal.com Volume 1 Issue 2 2012 The Journal of Phytopharmacology (Pharmacognosy and Phytomedicine Research) Phytopharmacology of Indian plant Sesbania grandiflora L. Suresh Kashyap *1 , Sanjay Mishra 1 1. Rakshpal Bahadur College of Pharmacy, Bareilly-243001 [Email: [email protected]] Abstract: Sesbania grandiflora L. is an Indian medicinal plant which belongs to family Leguminosae. It is cultivated in south or west India in the ganga valley and in Bengal. The plant contains rich in tanins, flavonoides, coumarins, steroids and triterpens. The plant used in colic disorder, jaundice, poisoning condition, small-pox, eruptive fever, epilepsy etc. The present work is carried out on phytopharmacological survey of the plant. Keywords: Sesbania grandiflora, Plant, Biological source, Phytopharmacology Introduction: Plant drug profile Biological source Plant name - Sesbania grandiflora L. It consist of dried leaves of Sesbania Synonym – Agati grandiflora L. grandiflora L. , belonging to the family English – Agati sesban , Swamp pea Leguminosae. 1 Ayurvedic – Agastya, agasti, munidrum, Geographical source muni, vangasena, vakrapushpa, kumbha It is cultivated in south or west India in the Siddha/Tamil – Agatti ganga valley and in Bengal. It is believed to have originated either in India or Southeast Volume 1 Issue 2 2012 | THE JOURNAL OF PHYTOPHARMACOLOGY 63 Suresh et. al. www.phytopharmajournal.com Asia and grows primarily in hot and humid Macroscopical character 4 areas of the world. Sesbania is found from Sesbania grandiflora L. is a small erect, northern Luzon to Mindanao in settled areas fast-growing, and sparsely branched tree that at low and medium altitudes. It was certainly reaches 10 m in height. -

Sesbania Rostrata Scientific Name Sesbania Rostrata Bremek

Tropical Forages Sesbania rostrata Scientific name Sesbania rostrata Bremek. & Oberm. Synonyms Erect annual or short-lived perennial 1– Leaves paripinnate with mostly12-24 3m tall pairs of pinnae None cited in GRIN. Family/tribe Family: Fabaceae (alt. Leguminosae) subfamily: Faboideae tribe: Sesbanieae. Morphological description Erect, suffrutescent annual or short-lived perennial, 1‒3 Inflorescence an axillary raceme Seeds m tall, with pithy sparsely pilose stems to 15 mm thick comprising mostly 3-12 flowers (more mature stems glabrescent); root primordia protruding up to 3 mm in 3 or 4 vertical rows up the stem. Leaves paripinnate (4.5‒) 7‒25 cm long; stipules linear-lanceolate, 5‒10 mm long, reflexed, pilose, persistent; petiole 3‒8 mm long, pilose; rachis up to 19 cm long, sparsely pilose; stipels present at most petiolules; pinnae opposite or nearly so, in (6‒) 12‒24 (‒27) pairs, oblong, 0.9‒3.5 cm × 2‒10 mm, the basal Incorporating into rice fields pair usually smaller than the others, apex rounded to Seedlings in rice straw obtuse to slightly emarginate, margins entire, glabrous above, usually sparsely pilose on margins and midrib beneath. Racemes axillary, (1‒) 3‒12 (‒15) - flowered; rachis pilose 1‒6 cm long (including peduncle 4‒15 mm); bracts and bracteoles linear-lanceolate, pilose; pedicels pedicel 4‒15 (‒19) mm long, sparsely pilose. Calyx sparsely pilose; receptacle 1 mm, calyx tube 4.5 mm long; teeth markedly acuminate, with narrow sometimes almost filiform tips 1‒2 mm long. Corolla yellow or orange; suborbicular, 12‒16 (‒18) mm × 11‒14 (‒15) mm; wings 13‒17 mm × 3.5‒5 mm, yellow, a small triangular tooth and the upper margin of the basal half of Stem nodules, Benin the blade together characteristically inrolled; keel 12‒17 mm × 6.5‒9 mm, yellow to greenish, basal tooth short, triangular, slightly upward-pointing with small pocket below it on inside of the blade; filament sheath 11‒13 mm, free parts 4‒6 mm, anthers 1 mm long. -

ISTA List of Stabilized Plant Names 7Th Edition

ISTA List of Stabilized Plant Names th 7 Edition ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. M. Schori Published by All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be The Internation Seed Testing Association (ISTA) reproduced, stored in any retrieval system or transmitted Zürichstr. 50, CH-8303 Bassersdorf, Switzerland in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior ©2020 International Seed Testing Association (ISTA) permission in writing from ISTA. ISBN 978-3-906549-77-4 ISTA List of Stabilized Plant Names 1st Edition 1966 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Prof P. A. Linehan 2nd Edition 1983 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. H. Pirson 3rd Edition 1988 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. W. A. Brandenburg 4th Edition 2001 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. J. H. Wiersema 5th Edition 2007 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. J. H. Wiersema 6th Edition 2013 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. J. H. Wiersema 7th Edition 2019 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. M. Schori 2 7th Edition ISTA List of Stabilized Plant Names Content Preface .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Symbols and Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................... -

Fruits and Seeds of Genera in the Subfamily Faboideae (Fabaceae)

Fruits and Seeds of United States Department of Genera in the Subfamily Agriculture Agricultural Faboideae (Fabaceae) Research Service Technical Bulletin Number 1890 Volume I December 2003 United States Department of Agriculture Fruits and Seeds of Agricultural Research Genera in the Subfamily Service Technical Bulletin Faboideae (Fabaceae) Number 1890 Volume I Joseph H. Kirkbride, Jr., Charles R. Gunn, and Anna L. Weitzman Fruits of A, Centrolobium paraense E.L.R. Tulasne. B, Laburnum anagyroides F.K. Medikus. C, Adesmia boronoides J.D. Hooker. D, Hippocrepis comosa, C. Linnaeus. E, Campylotropis macrocarpa (A.A. von Bunge) A. Rehder. F, Mucuna urens (C. Linnaeus) F.K. Medikus. G, Phaseolus polystachios (C. Linnaeus) N.L. Britton, E.E. Stern, & F. Poggenburg. H, Medicago orbicularis (C. Linnaeus) B. Bartalini. I, Riedeliella graciliflora H.A.T. Harms. J, Medicago arabica (C. Linnaeus) W. Hudson. Kirkbride is a research botanist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Systematic Botany and Mycology Laboratory, BARC West Room 304, Building 011A, Beltsville, MD, 20705-2350 (email = [email protected]). Gunn is a botanist (retired) from Brevard, NC (email = [email protected]). Weitzman is a botanist with the Smithsonian Institution, Department of Botany, Washington, DC. Abstract Kirkbride, Joseph H., Jr., Charles R. Gunn, and Anna L radicle junction, Crotalarieae, cuticle, Cytiseae, Weitzman. 2003. Fruits and seeds of genera in the subfamily Dalbergieae, Daleeae, dehiscence, DELTA, Desmodieae, Faboideae (Fabaceae). U. S. Department of Agriculture, Dipteryxeae, distribution, embryo, embryonic axis, en- Technical Bulletin No. 1890, 1,212 pp. docarp, endosperm, epicarp, epicotyl, Euchresteae, Fabeae, fracture line, follicle, funiculus, Galegeae, Genisteae, Technical identification of fruits and seeds of the economi- gynophore, halo, Hedysareae, hilar groove, hilar groove cally important legume plant family (Fabaceae or lips, hilum, Hypocalypteae, hypocotyl, indehiscent, Leguminosae) is often required of U.S. -

Manchester Road Redevelopment District: Form-Based Code

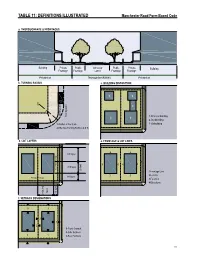

TaBle 11: deFiniTionS illuSTraTed manchester road Form-Based Code a. ThoroughFare & FronTageS Building Private Public Vehicular Public Private Building Frontage Frontage Lanes Frontage Frontage Private lot Thoroughfare (r.o.w.) Private lot b. Turning radiuS c. Building diSPoSiTion 3 3 2 2 1 Parking Lane Moving Lane 1- Principal Building 1 1 2- Backbuilding 1-Radius at the Curb 3- Outbuilding 2-Effective Turning Radius (± 8 ft) d. loT LAYERS e. FronTage & loT lineS 4 3rd layer 4 2 1 4 4 4 3 2nd layer Secondary Frontage 20 feet 1-Frontage Line 2-Lot Line 1st layer 3 3 Principal Frontage 3-Facades 1 1 4-Elevations layer 1st layer 2nd & 3rd & 2nd f. SeTBaCk deSignaTionS 3 3 2 1 2 1-Front Setback 2-Side Setback 1 1 3-Rear Setback 111 Manchester Road Form-Based Code ARTICLE 9. APPENDIX MATERIALS MBG Kemper Center PlantFinder About PlantFinder List of Gardens Visit Gardens Alphabetical List Common Names Search E-Mail Questions Menu Quick Links Home Page Your Plant Search Results Kemper Blog PlantFinder Please Note: The following plants all meet your search criteria. This list is not necessarily a list of recommended plants to grow, however. Please read about each PF Search Manchesterplant. Some may Road be invasive Form-Based in your area or may Code have undesirable characteristics such as above averageTab insect LEor disease 11: problems. NATIVE PLANT LIST Pests Plants of Merit Missouri Native Plant List provided by the Missouri Botanical Garden PlantFinder http://www.mobot.org/gardeninghelp/plantfinder Master Search Search limited to: Missouri Natives Search Tips Scientific Name Scientific Name Common NameCommon Name Height (ft.) ZoneZone GardeningHelp (ft.) Acer negundo box elder 30-50 2-10 Acer rubrum red maple 40-70 3-9 Acer saccharinum silver maple 50-80 3-9 Titles Acer saccharum sugar maple 40-80 3-8 Acer saccharum subsp.