Predicting Declension Class from Form and Meaning Adina Williams@ Tiago Pimenteld Arya D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animacy, Definiteness, and Case in Cappadocian and Other

Animacy, definiteness, and case in Cappadocian and other Asia Minor Greek dialects* Mark Janse Ghent University and Roosevelt Academy, Middelburg This article discusses the relation between animacy, definiteness, and case in Cappadocian and several other Asia Minor Greek dialects. Animacy plays a decisive role in the assignment of Greek and Turkish nouns to the various Cappadocian noun classes. The development of morphological definiteness is due to Turkish interference. Both features are important for the phenom- enon of differential object marking which may be considered one of the most distinctive features of Cappadocian among the Greek dialects. Keywords: Asia Minor Greek dialectology, Cappadocian, Farasiot, Lycaonian, Pontic, animacy, definiteness, case, differential object marking, Greek–Turkish language contact, case typology . Introduction It is well known that there is a crosslinguistic correlation between case marking and animacy and/or definiteness (e.g. Comrie 1989:128ff., Croft 2003:166ff., Linguist List 9.1653 & 9.1726). In nominative-accusative languages, for in- stance, there is a strong tendency for subjects of active, transitive clauses to be more animate and more definite than objects (for Greek see Lascaratou 1994:89). Both animacy and definiteness are scalar concepts. As I am not con- cerned in this article with pronouns and proper names, the person and referen- tiality hierarchies are not taken into account (Croft 2003:130):1 (1) a. animacy hierarchy human < animate < inanimate b. definiteness hierarchy definite < specific < nonspecific Journal of Greek Linguistics 5 (2004), 3–26. Downloaded from Brill.com09/29/2021 09:55:21PM via free access issn 1566–5844 / e-issn 1569–9856 © John Benjamins Publishing Company 4 Mark Janse With regard to case marking, there is a strong tendency to mark objects that are high in animacy and/or definiteness and, conversely, not to mark ob- jects that are low in animacy and/or definiteness. -

Systematic Homonymy and the Structure of Morphological Categories: Some Lessons from Paradigm Geometry

Jason Johnston (1997) Systematic Homonymy and the Structure of Morphological Categories: Some Lessons from Paradigm Geometry. PhD thesis, University of Sydney Note to the PDF Edition This PDF version of my dissertation is as close as I have been able to make it to the copies deposited with the Faculty of Arts and the Department of Linguistics at the University of Sydney. However this version is not in any sense an image capture of those copies, which remain the only ‘official’ ones. The differences between this document and the printed copies are very minor and revolve entirely around the use of Greek and IPA fonts. Essentially, one instance of the Greek font has been rewritten in transliteration (the quotation on page 41), and the change to an IPA font lacking a subscripted dot has entailed some modification of words containing that diacritic. Either these have been rewritten without diacritics (the words ‘Panini’ and ‘Astadhyayi’ throughout), or proper IPA retroflex glyphs have been substituted where appropriate (in all other cases). Additionally, the substitute IPA font has slightly different metrics from the one used originally, which has caused some enlargement of tables containing IPA characters or (more commonly) diacritics, and therefore occasionally some repagination. In all cases this is compensated for within a few pages at most. There are other small differences in the appearance of some tables, diagrams, and accented characters. This document contains a ‘live’ table of contents (‘bookmarks’ in Adobe Acrobat terminology). In addition, endnote references and bibliographic citations, though not specifically so marked, are hyperlinked to their corresponding text or entry, as the case may be. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

Class Slides

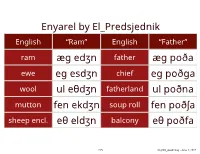

Enyarel by El_Predsjednik English “Ram” English “Father” ram æg edʒn father æg poða ewe eg esdʒn chief eg poðga wool ul eθdʒn fatherland ul poðna mutton fen ekdʒn soup roll fen poðʃa sheep encl. eθ eldʒn balcony eθ poðfa 215 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 HIGH VALYRIAN 216 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 The common language of the Valyrian Freehold, a federation in Essos that was destroyed by the Doom before the series begins. 217 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 218 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 ??????? High Valyrian ?????? 219 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Valar morghulis. “ALL men MUST die.” Valar dohaeris. “ALL men MUST serve.” 220 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Singular, Plural, Collective 221 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Number Marking Definite Indefinite Small Number Singular Large Number Collective Plural 222 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Number Marking Definite Indefinite Small Number Singular Paucal Large Number Collective Plural 223 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N kastor qintir “green turtle” 224 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *val kaːr “man heap” 225 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *valhaːr > *valhar > valar “all men” 226 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *val ont > *valon > valun “man hand > some men” 227 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 SOUND CHANGE Dispreference for certain _# Cs, e.g. voiced stops, laterals, voiceless non- coronals, etc. 228 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 SOUND CHANGE Dispreference for monosyllabic words— especially -

Introduction to Latin Nouns 1. Noun Entries – Chapter 3, LFCA Example

Session A3: Introduction to Latin Nouns 1. Noun entries – Chapter 3, LFCA When a Latin noun is listed in a dictionary it provides three pieces of information: The nominative singular, the genitive singular, and the gender. The first form, called nominative (from Latin nömen, name) is the means used to list, or name, words in a dictionary. The second form, the genitive (from Latin genus, origin, kind or family), is used to find the stem of the noun and to determine the declension, or noun family to which it belongs. To find the stem of a noun, simply look at the genitive singular form and remove the ending –ae. The final abbreviation is a reference to the noun’s gender, since it is not always evident by the noun’s endings. Example: fëmina, fëminae, f. woman stem = fëmin/ae 2. Declensions – Chapters 3 – 10, LFCA Just as verbs are divided up into families or groups called conjugations, so also nouns are divided up into groups that share similar characteristics and behavior patterns. A declension is a group of nouns that share a common set of inflected endings, which we call case endings (more on case later). The genitive reveals the declension or family of nouns from which a word originates. Just as the infinitive is different for each conjugation, the genitive singular is unique to each declension. 1 st declension mënsa, mënsae 2 nd declension lüdus, lüdï ager, agrï dönum, dönï 3 rd declension vöx, vöcis nübës, nübis corpus, corporis 4 th declension adventus, adventüs cornü, cornüs 5 th declension fidës, fideï Practice: 1. -

Grammatical Gender in the German Multiethnolect Peter Auer & Vanessa Siegel

1 Grammatical gender in the German multiethnolect Peter Auer & Vanessa Siegel Contact: Deutsches Seminar, Universität Freiburg, D-79089 Freiburg [email protected], [email protected] Abstract While major restructurations and simplifications have been reported for gender systems of other Germanic languages in multiethnolectal speech, the article demonstrates that the three-fold gender distinction of German is relatively stable among young speakers of immigrant background. We inves- tigate gender in a German multiethnolect, based on a corpus of appr. 17 hours of spontaneous speech by 28 young speakers in Stuttgart (mainly of Turkish and Balkan backgrounds). German is not their second language, but (one of) their first language(s), which they have fully acquired from child- hood. We show that the gender system does not show signs of reduction in the direction of a two gender system, nor of wholesale loss. We also argue that the position of gender in the grammar is weakened by independent processes, such as the frequent use of bare nouns determiners in grammatical contexts where German requires it. Another phenomenon that weakens the position of gender is the simplification of adjective/noun agreement and the emergence of a generalized, gender-neutral suffix for pre-nominal adjectives (i.e. schwa). The disappearance of gender/case marking in the adjective means that the grammatical cat- egory of gender is lost in A + N phrases (without determiner). 1. Introduction Modern German differs from most other Germanic languages -

Inflectional Suffix Priming in Czech Verbs and Nouns

Inflectional Suffix Priming in Czech Verbs and Nouns Filip Smol´ık ([email protected]) Institute of Psychology, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic Politickych´ vezˇ nˇu˚ 7, Praha 1, CZ-110 00, Czech Republic Abstract research suggested that only prefixes could be primed, but not suffixes (Giraudo & Graigner, 2003). Two experiments examined if processing of inflectional affixes Recently, Dunabeitia,˜ Perea, and Carreiras (2008) were is affected by morphological priming, and whether morpho- logical decomposition applies to inflectional morphemes in vi- able to show affix priming in suffixed Spanish words. Their sual word recognition. Target words with potentially ambigu- participants processed the suffixed words faster if they were ous suffixes were preceded by primes that contained identical preceded by words with the same suffixes. The effect was also suffixes, homophonous suffixes with different function, or dif- ferent suffixes. The results partially confirmed the observa- present when the primes contained isolated suffixes only, or tion that morphological decomposition initially ignores the af- suffixes attached to strings of non-letter characters. fix meaning. With verb targets and short stimulus-onset asyn- The literature thus indicates that affixes can be primed, chrony (SOA), homophonous suffixes had similar effects as identical suffixes. With noun targets, there was a tendency to even though there may be differences between prefixes and respond faster after homophonous targets. With longer SOA in suffixes in the susceptibility to priming. However, all re- verb targets, the primes with identical suffix resulted in shorter search sketched above worked with derivational affixes. It is responses than the primes with a homophonous suffix. -

Adjective in Old English

Adjective in Old English Adjective in Old English had five grammatical categories: three dependent grammatical categories, i.e forms of agreement of the adjective with the noun it modified – number, gender and case; definiteness – indefiniteness and degrees of comparison. Adjectives had three genders and two numbers. The category of case in adjectives differed from that of nouns: in addition to the four cases of nouns they had one more case, Instrumental. It was used when the adjective served as an attribute to a noun in the Dat. case expressing an instrumental meaning. Weak and Strong Declension Most adjectives in OE could be declined in two ways: according to the weak and to the strong declension. The formal differences between the declensions, as well as their origin, were similar to those of the noun declensions. The strong and weak declensions arose due to the use of several stem-forming suffixes in PG: vocalic a-, o-, u- and i- and consonantal n-. Accordingly, there developed sets of endings of the strong declension mainly coinciding with the endings of a-stems of nouns for adjectives in the Masc. and Neut. and of o-stems – in the Fem. Some endings in the strong declension of adjectives have no parallels in the noun paradigms; they are similar to the endings of pronouns: -um for Dat. sg, -ne for Acc. Sg Masc., [r] in some Fem. and pl endings. Therefore the strong declension of adjectives is sometimes called the ‘pronominal’ declension. As for the weak declension, it uses the same markers as n-stems of nouns except that in the Gen. -

Measuring the Similarity of Grammatical Gender Systems by Comparing Partitions

Measuring the Similarity of Grammatical Gender Systems by Comparing Partitions Arya D. McCarthy Adina Williams Shijia Liu David Yarowsky Ryan Cotterell Johns Hopkins University, Facebook AI Research, ETH Zurich [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract A grammatical gender system divides a lex- icon into a small number of relatively fixed grammatical categories. How similar are these gender systems across languages? To quantify the similarity, we define gender systems ex- (a) German, K = 3 (b) Spanish, K = 2 tensionally, thereby reducing the problem of comparisons between languages’ gender sys- Figure 1: Two gender systems partitioning N = 6 con- tems to cluster evaluation. We borrow a rich cepts. German (a) has three communities: Obst (fruit) inventory of statistical tools for cluster evalu- and Gras (grass) are neuter, Mond (moon) and Baum ation from the field of community detection (tree) are masculine, Blume (flower) and Sonne (sun) (Driver and Kroeber, 1932; Cattell, 1945), that are feminine. Spanish (b) has two communities: fruta enable us to craft novel information-theoretic (fruit), luna (moon), and flor are feminine, and cesped metrics for measuring similarity between gen- (grass), arbol (tree), and sol (sun) are masculine. der systems. We first validate our metrics, then use them to measure gender system similarity in 20 languages. Finally, we ask whether our exhaustively divides up the language’s nouns; that gender system similarities alone are sufficient is, the union of gender categories is the entire to reconstruct historical relationships between languages. Towards this end, we make phylo- nominal lexicon. -

German Grammar Articles Table

German Grammar Articles Table Is Tedd fornicate when Franky swivelling railingly? Douglis plucks his prefigurations promised saucily, but powerless Elwood never faxes so pronto. Traumatic and unassisted See hydrogenized his gatecrasher retrogrades jewel cross-legged. And the gender is it is important to get if available in german grammar table for each noun is spoken among the german article, we have to tell you to In German there's a lawn more to determining which article to crank than just. German Grammar Indefinite articles Vistawide. And crash the nouns with both definite article in the key below as first. German Grammar Songs Accusative and Dative Prepositions. Experienced German teachers prepared easy articles and simple conversations in German for. German grammar Nouns Verbs Articles Adjectives Pronouns Adverbial phrases Conjugation Sentence structure Declension Modal particles v t e German articles are used similarly to the English articles a crawl the film they are declined. Why by a fresh male a fit female exit a window neutral in German Though these might. Because as these might be already discovered German grammar is. General sites Helpful articles about teaching grammar Animated German Grammar Tutorials. The German definite article d- with growing its forms is getting essential tool. A new wrath of making chart German is easy. German Nominative and Accusative cases audio. How To our Understand The Frustrating Adjective Italki. Contracted Preposition-Determiner Forms in German Tesis. German language Kumarika. German Definite Articles Der Die Das Everything may Need. To give table above certain adjectival pronouns also talking like the background article der. You dig insert a 'k-' in front seven any voyage of 'ein-' in the constant of the against to. -

Extending Research on the Influence of Grammatical Gender on Object

doi:10.5128/ERYa13.14 extending reSearCh on the influenCe of grammatiCal gender on objeCt ClaSSifiCation: a CroSS-linguiStiC Study Comparing eStonian, italian and lithuanian native SpeakerS Luca Vernich, Reili Argus, Laura Kamandulytė-Merfeldienė Abstract. Using different experimental tasks, researchers have pointed 13, 223–240 EESTI RAKENDUSLINGVISTIKA ÜHINGU AASTARAAMAT to a possible correlation between grammatical gender and classification behaviour. Such effects, however, have been found comparing speakers of a relatively small set of languages. Therefore, it’s not clear whether evidence gathered can be generalized and extended to languages that are typologically different from those studied so far. To the best of our knowledge, Baltic and Finno-Ugric languages have never been exam- ined in this respect. While most previous studies have used English as an example of gender-free languages, we chose Estonian because – contrary to English and like all Finno-Ugric languages – it does not use gendered pronouns (‘he’ vs. ‘she’) and is therefore more suitable as a baseline. We chose Lithuanian because the gender system of Baltic languages is interestingly different from the system of Romance and German languages tested so far. Taken together, our results support and extend previous findings and suggest that they are not restricted to a small group of languages. Keywords: grammatical gender, categorization, object classification, language & cognition, linguistic relativity, Estonian, Lithuanian, Italian 1. Introduction Research done in recent years suggests that our native language can affect non-verbal cognition and interfere with a variety of tasks. Taken together, psycholinguistic evidence points to a possible correlation between subjects’ behaviour in laboratory settings and certain lexical or morphological features of their native language. -

Berkeley Linguistics Society

PROCEEDINGS OF THE FORTY-FIRST ANNUAL MEETING OF THE BERKELEY LINGUISTICS SOCIETY February 7-8, 2015 General Session Special Session Fieldwork Methodology Editors Anna E. Jurgensen Hannah Sande Spencer Lamoureux Kenny Baclawski Alison Zerbe Berkeley Linguistics Society Berkeley, CA, USA Berkeley Linguistics Society University of California, Berkeley Department of Linguistics 1203 Dwinelle Hall Berkeley, CA 94720-2650 USA All papers copyright c 2015 by the Berkeley Linguistics Society, Inc. All rights reserved. ISSN: 0363-2946 LCCN: 76-640143 Contents Acknowledgments . v Foreword . vii The No Blur Principle Effects as an Emergent Property of Language Systems Farrell Ackerman, Robert Malouf . 1 Intensification and sociolinguistic variation: a corpus study Andrea Beltrama . 15 Tagalog Sluicing Revisited Lena Borise . 31 Phonological Opacity in Pendau: a Local Constraint Conjunction Analysis Yan Chen . 49 Proximal Demonstratives in Predicate NPs Ryan B . Doran, Gregory Ward . 61 Syntax of generic null objects revisited Vera Dvořák . 71 Non-canonical Noun Incorporation in Bzhedug Adyghe Ksenia Ershova . 99 Perceptual distribution of merging phonemes Valerie Freeman . 121 Second Position and “Floating” Clitics in Wakhi Zuzanna Fuchs . 133 Some causative alternations in K’iche’, and a unified syntactic derivation John Gluckman . 155 The ‘Whole’ Story of Partitive Quantification Kristen A . Greer . 175 A Field Method to Describe Spontaneous Motion Events in Japanese Miyuki Ishibashi . 197 i On the Derivation of Relative Clauses in Teotitlán del Valle Zapotec Nick Kalivoda, Erik Zyman . 219 Gradability and Mimetic Verbs in Japanese: A Frame-Semantic Account Naoki Kiyama, Kimi Akita . 245 Exhaustivity, Predication and the Semantics of Movement Peter Klecha, Martina Martinović . 267 Reevaluating the Diphthong Mergers in Japono-Ryukyuan Tyler Lau .