Becoming a Subway User: Managing Affects and Experiences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A State of the Union: Federation and Autonomy in Tatarstan Abigail Stowe-Thurston Macalester College, [email protected]

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College Russian Studies Honors Projects Russian Studies Spring 2016 A State of the Union: Federation and Autonomy in Tatarstan Abigail Stowe-Thurston Macalester College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/russ_honors Recommended Citation Stowe-Thurston, Abigail, "A State of the Union: Federation and Autonomy in Tatarstan" (2016). Russian Studies Honors Projects. Paper 1. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/russ_honors/1 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Russian Studies at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Russian Studies Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Honors Project Macalester College Spring 2016 A State of the Union: Federation and Autonomy in Tatarstan Author: Abigail Stowe-Thurston A State of the Union: Federation and Autonomy in Tatarstan Abigail Stowe-Thurston Advisor: James von Geldern Russian Studies Department 2 ABSTRACT Most research on the topic of center-periphery relations focuses on the center as the locus of policy. This project, on the other hand, seeks to establish an alternative understanding of the ways in which nationality has played out both as a Russian tactic to unite disparate and diverse territories, and as a mode by which some ethnic minorities in Russian-ruled spaces have been able to secure relative autonomy. The Republic of Tatarstan, located in the Volga River basin, has achieved unprecedented levels of autonomy while existing as a contingent part of the USSR, and now the Russian Federation. Comparisons have been drawn between Tatarstan and Chechnya in regards to the political, economic, and cultural autonomy they exercise on their respective territories; however, while their autonomy may be comparable, their respective relationships with the Russian central governments are not. -

5G for Trains

5G for Trains Bharat Bhatia Chair, ITU-R WP5D SWG on PPDR Chair, APT-AWG Task Group on PPDR President, ITU-APT foundation of India Head of International Spectrum, Motorola Solutions Inc. Slide 1 Operations • Train operations, monitoring and control GSM-R • Real-time telemetry • Fleet/track maintenance • Increasing track capacity • Unattended Train Operations • Mobile workforce applications • Sensors – big data analytics • Mass Rescue Operation • Supply chain Safety Customer services GSM-R • Remote diagnostics • Travel information • Remote control in case of • Advertisements emergency • Location based services • Passenger emergency • Infotainment - Multimedia communications Passenger information display • Platform-to-driver video • Personal multimedia • In-train CCTV surveillance - train-to- entertainment station/OCC video • In-train wi-fi – broadband • Security internet access • Video analytics What is GSM-R? GSM-R, Global System for Mobile Communications – Railway or GSM-Railway is an international wireless communications standard for railway communication and applications. A sub-system of European Rail Traffic Management System (ERTMS), it is used for communication between train and railway regulation control centres GSM-R is an adaptation of GSM to provide mission critical features for railway operation and can work at speeds up to 500 km/hour. It is based on EIRENE – MORANE specifications. (EUROPEAN INTEGRATED RAILWAY RADIO ENHANCED NETWORK and Mobile radio for Railway Networks in Europe) GSM-R Stanadardisation UIC the International -

Experience of European and Moscow Metro Systems

EU AND ITS NEIGHBOURHOOD: ENHANCING EU ACTORNESS IN THE EASTERN BORDERLANDS • EURINT 2020 | 303 DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION OF TRANSPORT INFRASTRUCTURE: EXPERIENCE OF EUROPEAN AND MOSCOW METRO SYSTEMS Anton DENISENKOV*, Natalya DENISENKOVA**, Yuliya POLYAKOVA*** Abstract The article is devoted to the consideration of the digital transformation processes of the world's metro systems based on Industry 4.0 technologies. The aim of the study is to determine the social, economic and technological effects of the use of digital technologies on transport on the example of the metro, as well as to find solutions to digitalization problems in modern conditions of limited resources. The authors examined the impact of the key technologies of Industry 4.0 on the business processes of the world's subways. A comparative analysis of the world's metros digital transformations has been carried out, a tree of world's metros digitalization problems has been built, a reference model for the implementation of world's metros digital transformation is proposed. As the results of the study, the authors were able to determine the social, economic and technological effects of metro digitalization. Keywords: Industry 4.0 technologies, digital transformation, transport, metro Introduction The coming era of the digital economy requires a revision of business models, methods of production in all spheres of human life in order to maintain competitive advantages in the world arena. The transport industry is no exception, as it plays an important role in the development of the country's economy and social sphere. The Metro is a complex engineering and technical transport enterprise, dynamically developing taking into account the prospects for expanding the city's borders, with an ever-increasing passenger traffic and integration into other public transport systems. -

Reference List 1994-2020 Reference-List 2020 2

1 1 pluton.ua REFERENCE LIST 1994-2020 REFERENCE-LIST 2020 2 CONTENTS 3 METRO 23 CITY ELECTRIC TRANSPORT 57 RAILWAYS 69 INDUSTRIAL, IRON AND STEEL, MACHINE-BUILDING, RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT ENTERPRISES 79 POWER INDUSTRY 2 3 METRO UKRAINE RUSSIAN FEDERATION KHARKIV METRO 4 YEKATERINBURG METRO 16 KYIV METRO 6 MOSCOW METRO 18 KAZAN METRO 18 REPUBLIC OF KAZAKHSTAN NIZHNY NOVGOROD METRO 19 ALMATY METRO 8 ST. PETERSBURG METRO 19 REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN REPUBLIC OF UZBEKISTAN BAKU METRO 10 TASHKENT METRO 20 REPUBLIC OF BELARUS ROMANIA MINSK METRO 14 BUCHAREST METRO 20 REPUBLIC OF KOREA BUSAN СITY METRO 21 DAWONSYS COMPANY 21 REPUBLIC OF TURKEY IZMIR METRO 21 REFERENCE-LIST 2020 4 KHARKIV METRO KHARKIV, UKRAINE Turn-key projects: 2003- 3 traction substations of 23 Serpnia, Botanichnyi Sad, Oleksiivska NEX Switchgear 6 kV 1 set 2009 metro stations. NEX Switchgear 10 kV 1 set Supply of equipment, installation works, commissioning, startup. DC Switchgear 825 V 26 units 2016 Traction substation of Peremoha metro station. Transformer 10 units Supply of equipment, installation supervision, commissioning, Rectifier 12 units startup. Telecontrol equipment 1 set 2017 Tunnel equipment for the dead end of Istorychnyi Muzei metro station and low voltage equipment for Kharkiv Metro AC Switchgear 0.23...0.4 kV 5 sets Administration building power supply. DC Distribution Board 2 sets Supply of equipment, installation, commissioning. Communications Based Train Control Switchgear 2 sets Equipment for tunnels and depots: Line Disconnector Cabinet 15 units Implemented -

Transport Mobility of Russian Super-Large Cities

E3S Web of Conferences 274, 13006 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202127413006 STCCE – 2021 Transport mobility of Russian super-large cities Ramil Zagidullin1, and Rumiya Mukhametshina1[0000-0002-1215-263x] 1Kazan State University of Architecture and Engineering, 420043 Kazan, Russia Abstract. The relevance of the issue under study stems from the lack of a method and indicators for determining the population’s level of transport mobility. The purpose of the article is to develop a method for assessing the level of transport mobility. The analysis of studies on the quality of transport services has shown lack of attention to mobility as a public transport service for the public. There are currently no science-based criteria for assessing the mobility level of convenience for passengers who use various modes of public transport for their trips. The use of a transport mobility index will improve both the quality of passenger transport and the overall level of transport services. The developed method for assessing the level of transport mobility will allow researchers to look into the dynamics of the indicators and plan improvements to transport service quality. The presence of a well- developed metro network (more than one line) in cities provides a transport mobility index above 0.5, according to the study of Russia’s largest cities’ transport mobility index. Following the example of Rostov-on-Don, which has the smallest area of the cities under study, a high transport mobility index of 0.6 can be achieved through optimal organization of public transport within the city and without a metro network. -

Time Systems and Clocks for Railways and Metros – State of the Art

Time Systems and Clocks for Railways Time Systems and Clocks – Time Reference Company and Metros MOBATIME is the leading brand for innovative time display, time distribution and time reference systems. MOBATIME-Solutions to meet your requirements Equipments and components are developed, manufactured and promoted by Moser-Baer Ltd., Switzerland. MOBATIME offers practical experience and extensive technology know-how in time systems for a wide range of Do you want to: application fields. This includes outdoor and indoor clocks, clock movements, master clocks and time servers. :: administrate, control and monitor your time system of a whole country, region or specific line out of the central Operation Control Center (OCC)? Application Fields :: integrate your time system in the superior management system of your railway and metro infrastructure? :: provide a reliable time reference for computer controlled systems such as CCTV, Ticketing, Airports Hospitals Industries Access Control, Passenger Information System, etc.? :: service your railway and metro clocks upon incidence in order to reduce related maintenance costs? Railway Stations Universities/Schools Power Plants :: reduce your power consumption of the clocks with a LED illumination? :: protect your slave clocks from vandalism and save repair costs? Underground Stations Public Buildings Radio/TV Studios :: boost your corporate identity with slave clocks in line with your corporate design? References MOBATIME-Solutions: Railways/Metros Switzerland · Germany · Iran · Portugal · Holland · -

Guidance Materials for Conducting a Worldskills Kazan 2019 Lesson in Educational Institutions of the Russian Federation the Guid

Authors and originators: N.S. Koroleva, G.T. Gabdullina, N.P. Orlova, E.E. Ulyanova Guidance materials for conducting a WorldSkills Kazan 2019 Lesson in educational institutions of the Russian Federation The guidelines contain materials on the WorldSkills Kazan 2019 for teaching staff of general education, specialized secondary and higher education establishments. The guidelines provide plan-abstracts of the WorldSkills Kazan 2019 Lesson for different age groups of students, tasks and exercises for the use in subsequent lessons dedicated to the Competition, information on the history, venues, sports, symbols and volunteer movement of the Competition. The guidelines are accompanied by a DVD with videos, presentations, and songs about the WorldSkills Kazan 2019, as well as with an electronic copy of these guidelines. INTRODUCTION On 10 August 2015, at the WorldSkills General Assembly in San Paulo (Brazil), Russia won the right to host the WorldSkills Competition in 2019 (hereinafter, the Competition). It will be the 45th WorldSkills Competition in Kazan. The areas of activities of WorldSkills International are: jobs promotion career building education and professional training international cooperation research of professional skills organization of WorldSkills Competitions, the largest professional skill competitions. In the Republic of Tatarstan, the preparations for 45th WorldSkills Competition in 2019 have been performed since 2015, and these preparations are so large-scale that they affect all society life spheres and all population groups. The academic year before the WorldSkills Competition starts on 1 September 2018. This event, along with the annual Knowledge Day, will be a milestone and will allow to popularize the Competition among students who have yet to choose a profession. -

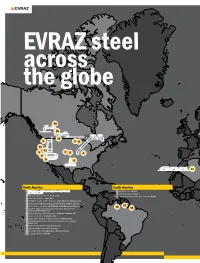

Save PDF Evraz Steel Across the Globe

EVRAZ steel across the globe 58 54 34 57 61 51 42 32 33 44 62 46 45 53 60 49 59 47 50 39 40 14 35 38 52 48 20 15 43 63 56 23 25 55 5.0 65 13 21 41 7 6 11 36 64 10 37 12 29 1 2 5 26 4 19 30 31 8 27 24 28 9 3 22 69 68 71 North America South America 1 BART high-speed t rain system (Bay Area Rapid Transit) 16 Vli Rail Operator (Brazil) 70 (San Francisco, US) 17 Rumo ALL Railway (Brazil) 2 RTD regional road network (Denver, US) 18 Road for Klabin pulp and paper company (Brazil) 3 Texas Capital metro (Texas, US) 4 Enbridge Flanagan South oil pipeline (From Illinois to Oklahoma, US) 66 5 Kinder Morgan Rockies Express gas pipeline (From Colorado to Ohio, US) 17 6 Dakota Access oil pipeline (North Dakota, South Dakota and Illinois, US) 16 7 Seattle-Portland passenger rail Point Defiance Bypass Project 18 (Lakewood, Washington, US) 67 8 Water supply pipe, AMERON project (Southern California, US) 9 Apple headquarters (California, US) 10 Barges at the Gunderson Marine Shipyard (Portland, US) 11 250,000 barrel oil tanks, Great Basin Industrial project (North Dakota, US) 12 Wilshire Tower high-rise (Los Angeles, US) 13 Southwest Light Rail Transit Minnesota 14 Oil tank floating roof (Calgary Cove, Alberta, Canada) 15 TC Energy pipeline (Canada) 54 Annual report & Accounts 2019 Strategic report Business review CSR report Corporate governance Financial statements Additional information Europe Russia 19 Turkish State Railway (TCDD) (Turkey) 32 Pella Shipyard (Leningrad region) 49 Baikal-Amur Railway (Siberia, Russian Far East) 20 Deutsche Bahn (Germany) -

The Rise and Decline of Ethnic Mobilization and Sovereignty in Tatarstan

THE RISE AND DECLINE OF ETHNIC MOBILIZATION AND SOVEREIGNTY IN TATARSTAN A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY DENİZ DİNÇ IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS JUNE 2017 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Tülin Gençöz Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Prof. Dr. Özlem Tür Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Assoc. Prof. Dr. Işık Kuşçu Assoc. Prof. Dr. Mustafa Şen Co-Supervisor Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Fethi Açıkel (Ankara Uni., SBKY) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Mustafa Şen (METU, SOC) Prof. Dr. Oktay Tanrısever (METU, IR) Prof. Dr. Taşansu Türker (Ankara Uni., SBKY) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Pınar Bedirhanoğlu (METU, IR) I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Deniz Dinç Signature : iii ABSTRACT THE RISE AND DECLINE OF ETHNIC MOBILIZATION AND SOVEREIGNTY IN TATARSTAN Dinç, Deniz Ph.D., Department of International Relations Supervisor : Assoc. Prof. Dr. Mustafa Şen Co-Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Dr. -

Kazan Metro Kazan, Tatarstan

Customer Success Story Kazan Metro Kazan, Tatarstan A Metro Train Departing a Station The design of the Kazan Metro control system origi- nated at the St. Petersburg NII Scientific Research Insti- tute, with special attention paid to safety and mechanics, while experimental testing was performed in the city of Neva. When opened, the Kazan Metro was unique in that it boasted the complete absence of now obsolete relays, historically used for motion control and management in metros throughout the country. More contemporary on- board and station computing resources were adopted, each capable of determining conditions throughout the metro infrastructure, ensuring passenger safety. ICONICS Software Deployed The Kazan Metro selected ICONICS’ GENESIS32™ Kazan Metro Monitoring Screen Web-enabled, OPC-based HMI/SCADA suite for its control and visualization system, as well as the Data- WorX™32 component for OPC data aggregation, bridg- About Kazan Metro ing, redundancy and tunneling. Kazan is the capital of Tatarstan, a republic in the Rus- sian Federation, located 800 kilometers (497 miles) east Project Summary of Moscow, with a population of nearly 1.5 million resi- The new Kazan Metro required a unified control and vi- dents. Planners of the Kazan Metro (or “Underground”) sualization system for its operation. The objectives for intended to have the system operational for Kazan’s this solution were the management and security of in- Millennium Celebration in 2005 and completed Phase tegrated systems including Train Dispatch and Control, One of their plan by completing five stations with 9 km Antiterrorist Protection, Power Systems/Uninterrupted (over 5.5 miles) of underground and 4 km (nearly 2.5 Power Supplies, Fire Safety, Groundwater Pumping and miles) of above ground rail by that deadline. -

Rail, Metro and Tram Networks in Russia

Rail, Metro and Tram Networks in Russia – 2012 – Brooks Market Intelligence Reports, part of Mack Brooks Exhibitions Ltd www.brooksreports.com Mack Brooks Exhibitions Ltd © 2012. All rights reserved. No guarantee can be given as to the correctness and/or completeness of the information provided in this document. Users are recommended to verify the reliability of the statements made before making any decisions based on them. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 1. DEVELOPMENT OF THE RUSSIAN RAILWAY NETWORK 5 2. THE RUSSIAN RAILWAY NETWORK 8 The Russian Rail Network – Key Data 8 RZD Traction and Rolling Stock 9 RZD Traffic in 2011 9 RZD Financial Highlights 10 RZD investment plans by 2015 and 2020 10 Network Map Sources 11 The 16 RZD Geographical Operating Divisions 11 Kaliningrad Division 11 Moskva Division 12 October Division 13 Northern Division 15 Gorky Division 15 Southeastern Division 15 North Caucasus Division 16 Kuibishev Division 17 Privolzhsk Division 17 Sverdlovsk Division 18 South Urals Division 18 West Siberian Division 19 Krasnoyarsk Division 19 East Siberian Division 20 Trans-Baikal Division 21 Far Eastern Division 21 3. CURRENT MAJOR INFRASTRUCTURE PROJECTS 24 New Railways 24 High-Speed Network 24 Far East to Europe Freight Corridors 27 The BAM and the Bering Strait Project 27 Europe and Russia to Southeast Asia 28 The China Gateway Project 28 Western Siberia 29 2014 Winter Olympics 29 International Cooperation on Signalling Technology 30 4. RAILFREIGHT IN RUSSIA 31 Open Access 33 Selected Principal Railfreight Companies 35 ASCOP Members in 2012 39 Mack Brooks Exhibitions Ltd © 2012 2 5. PASSENGER RAIL SERVICES IN RUSSIA 44 RZD Subsidiaries 44 Other Passenger Operators 49 6. -

Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6

Chapter 1 Introduction . 4 CONTENTS Chapter 2 Events of the year . 6 Chapter 3 Key performance indicators . 20 Chapter 4 Development and technical modernization . 40 Chapter 5 Public safety . 60 Chapter 6 Moscow metro people . 72 Chapter 7 International activities . 92 Chapter 8 Moscow metro today . 100 3 Introduction Introduction chapter chapter 1 1 Dear Friends, Metro system is a synergy of labour and science, complicated engineering design and strong discipline. Moscow metro, one of the best transport systems of the world is the appropriate combination of these factors. In 2007 we accomplished good results. Within several months at the beginning of the year we opened four new stations for the public use. And in August we opened one more, Trubnaya station which at once became one of the most frequently used interchange stations. In December we opened Sretensky Bulvar station and before the New Year the fi rst train ran from the new Kuntsevskaya station on Arbatsko-Pokrovskaya line to the long awaited Strogino station. At present the route length of Moscow metro is about three hundred kms and the number of stations is nearly two hundred. We expect to continue our development at a good pace. Due to fi nancial and administrative support of the Government of Moscow in the new century metro construction has been progressing fast and with good quality results. We have done much to upgrade our rolling stock and other technical devices. During the passed year our depots received several batches of new cars to replace the out-of-date stock. At the same time we refurbished the previous generations stock to fi t the up-to-date standards.