Necroperformance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Osobowości Prawnej, Którym Udzielono Pomocy Publicznej W 2020 Roku

Wykaz osób prawnych i fizycznych oraz jednostek organizacyjnych nie posiadających osobowości prawnej, którym udzielono pomocy publicznej w 2020 roku Lp Nazwa beneficjenta 1 Wojciech Borowski 2 TDM Electronics S.A. 3 AUTO FULL SERWIS Ireneusz Ciołkiewicz 4 ELEKTROPLAN "S M T" STANISŁAW SARNECKI 5 I ACCOUNT SP. Z O.O. 6 ALPI HUMMUS Aleksandra Marciniak 7 ARKADIUSZ BUDEK PROFIT 8 Mechanika u Wojtasa Wojciech Wasielak 9 ELECTRAPLAN SMT SP. ZO.O. 10 Przedszkole Niepubliczne Sióstr Służebniczek Niepokalanego Poczęcia N.M.P im. E. 11 Stowarzyszenie Perły Mazowsza - Lokalna Grupa Działania 12 Filip Olejnik ROBOTY ZIEMNE 13 Cukiernia "Karpatka" S.C. 14 Firma Handlowo-Produkcyjno-Usługowa "JATO" Cieślak Grażyna 15 NailStory 16 Sklep Kosmetyczny Anna Jankowska 17 Cukiernia "Karpatka" S.C. 18 NailStory 19 POSEJDON Marek Hiczewski 20 Sklep Kosmetyczny Anna Jankowska 21 POSEJDON Marek Hiczewski 22 AGA - CATERING Agnieszka Sztender 23 USŁUGI TRANSPORTOWE Jacek Osuch 24 Wiesława TOMALA SALON FRYZJERSKI Wiesława Tomala 25 Studio Fryzur Mariusz Napiórkowski i Spółka s. c. 26 ARAK TRANS LOGISTIC Krzysztof Arak 27 AUTOMANIAK Piotr Pyl 28 BIG-TRANS Robert Plaskota 29 NOVATIO MICHAŁ MICHTA 30 DĄBBUD-ZAKŁAD BUDOWNICTWA OGÓLNEGO TADEUSZ DĄBROWSKI 31 PHU Barbara Sęgnik 32 "DOMINI" - Łuczyńska Grażyna 33 FEST KATARZYNA GURANOWSKA 34 Firma Handlowa TRIUMF Zafer Demirseren 35 JAKIMIUK KRZYSZTOF - P. W. KRIS 36 "JULIA" HURTOWO-DETALICZNA SPRZEDAŻ JAJ. TRANSPORT DORIAN KUCZABA VEL KUCIABIŃSK 37 KATARZYNA MICHALAK 38 KOSMA JACEK SUTKOWSKI 39 Monia Monika Błyskal w Mysiadle 40 MOTO KLINIKA SEBASTIAN KUROWSKI 41 Piotr Wolniak 42 MONIA MONIKA BŁYSKAL 43 MOTO KLINIKA SEBASTIAN KUROWSKI 44 NOVATIO MICHAŁ MICHTA 45 PHU Barbara Sęgnik 46 Piotr Wolniak 47 Studio Fryzur Mariusz Napiórkowski i Spółka s. -

178 Chapter 6 the Closing of the Kroll: Weimar

Chapter 6 The Closing of the Kroll: Weimar Culture and the Depression The last chapter discussed the Kroll Opera's success, particularly in the 1930-31 season, in fulfilling its mission as a Volksoper. While the opera was consolidating its aesthetic identity, a dire economic situation dictated the closing of opera houses and theaters all over Germany. The perennial question of whether Berlin could afford to maintain three opera houses on a regular basis was again in the air. The Kroll fell victim to the state's desire to save money. While the closing was not a logical choice, it did have economic grounds. This chapter will explore the circumstances of the opera's demise and challenge the myth that it was a victim of the political right. The last chapter pointed out that the response of right-wing critics to the Kroll was multifaceted. Accusations of "cultural Bolshevism" often alternated with serious appraisal of the strengths and weaknesses of any given production. The right took issue with the Kroll's claim to represent the nation - hence, when the opera tackled works by Wagner and Beethoven, these efforts were more harshly criticized because they were perceived as irreverent. The scorn of the right for the Kroll's efforts was far less evident when it did not attempt to tackle works crucial to the German cultural heritage. Nonetheless, political opposition did exist, and it was sometimes expressed in extremely crude forms. The 1930 "Funeral Song of the Berlin Kroll Opera", printed in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, may serve as a case in point. -

Section 6 Language Corrected SN(1)

The Socio-Cultural Conditions of the Avant-Gardes in Finland in the 1920s and 1930s Stefan Nygård Abstract As a geopolitically strategic and newly independent country recovering from the trauma of a civil war in 1918, the socio-cultural constraints on artistic freedom were considerable in Finland between the wars. Art and literature were to a varying extent connected to political projects on the left or the right. Leading critics played a key role in the negotiations between art, politics and ideology. Few artists or writers, however, adjusted uncritically to external ideological demands. Those that challenged the subordination of art to political agendas or the national imperative often relied on the accumulation of symbolic capital abroad. With its separation from Russia in the winter of 1917–1918, and a civil war that involved active participation from German and Russian troops, Finland was more directly affected by World War I than its Scandinavian neighbours. The climate of post-war cultural and intellectual debate was partly determined by the violent beginning of independence, in addition to the increasingly totalising claims of the state throughout Europe between the wars. At the time Finland was a semi-democratic country with relative freedom of expression. Socialist parties were only partially tolerated, and approximately 4,000 people were sentenced in the so-called communist trials between 1919 and 1944 (Björne 2007: 498–499). Besides the tension between east and west and “red” and “white”, linguistic struggles between Finnish and Swedish added to the disintegrating forces. In the context of a desperate search for national unity and political stability in what is sometimes called the “white republic”, there was limited tolerance for the kind of radical questioning of core values in liberal bourgeois society that was common among the early twentieth-century avant-gardes. -

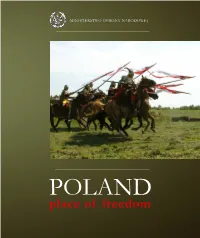

Place of Freedom Introduction of Christianity, 965 A.D

MINISTERSTWO OBRONY NARODOWEJ POLAND place of freedom Introduction of Christianity, 965 A.D. by Jan Matejko (1889) 2 POLAND’S BAPTISM AND THE RECOGNITION OF ITS INDEPENDENCE The coat of arms of Poland (1295-1569) A.D. 966 he lands situated between the Baltic Sea and the Carpathian Moun- tains, the Oder and Bug rivers, inhabited by the Polanie tribe came Tinto existence as a powerful country in the 10th century. This is the first reference to the country of Poland. In 966 Mieszko I, known as first historical ruler of Poland, opting for conversion from Rome, not Constantinople, chose the western over the eastern variant of European culture. This placed Poland between the two great sibling civilizations of medieval Christian Europe. A c o p y o f t h e o l d e s t P o l i s h w r t i n g s ‘ O l d Ś w i ę t o k r z y s k i e ’ n o t e d i n 9 6 6 : “Mieszko, the duke of Poland was baptized”. This year is considered to be the beginning of the evan- gelization of Poland and also the recognition of its state- hood. Missionaries and monks began arriving in the coun- try. The Latin language was introduced, reading and writing were taught, brick churches and monasteries were built, and modern agricultural methods were introduced. Savage pagan traditions were being replaced by efforts to live by the com- mandments of love as found in the Christian Decalogue. -

Ftaketettflugplafc Berlin

A 1015 F MITTEILUNGEN DES VEREINS FÜR DIE GESCHICHTE BERLINS GEGRÜNDET 1865 88. Jahrgang Heft 1 Januar 1992 Rcisbifoliofhek ig der Ber!!f»r StodtbiWiathe» Der „Bogenschütze" im Schloßpark von Sanssouci, Parterre der Neuen Orangerie, Aufnahme November 1990 (Foto: Schmidt) Plastiken in Berlin: Der „Bogenschütze" von Ernst Moritz Geyger Ein Berliner Bildhauer und sein populärstes Werk Von Martin H. Schmidt Nur schwer läßt sich die gigantisch erscheinende Skulptur des „Bogenschützen" von Ernst Moritz Geyger im Schloßpark von Sanssouci übersehen. Seit 1961 steht der — von dem Potsda mer „Blechner" Gustav Lind1 in Kupfer getriebene — nackte Jüngling im Parterre der Neuen Orangerie; er hatte ursprünglich (seit 1902) im Sizilianischen Garten und zwischenzeitlich (1927—1960) in der Nähe des Hippodroms Aufstellung gefunden. Folgende Bemerkungen seien zunächst dem Schöpfer des „Bogenschützen" gewidmet: Der Künstler Ernst Moritz Geyger — Sohn eines Schuldirektors2 — wurden am 9. November 1861 in Rixdorf (heute Berlin-Neukölln) geboren. Mit sechzehn Jahren begann er seine künst lerische Ausbildung in der Malklasse der Kunstschule in Berlin und setzte sie von 1878 bis 1883 an der akademischen Hochschule fort. Wie auf viele junge Künstler übte sein Lehrer, der Tier maler Paul Meyerheim, auf die früh entstandenen Gemälde und Graphiken des Eleven einen unübersehbaren Einfluß aus.3 Trotz positiver Erwähnungen aus den Reihen zeitgenössischer Kritiker scheiterte Geygers Versuch, im Atelier des staatstragenden Künstlers der Wilhelmini schen Ära, Anton von Werner, unterzukommen. Als Geygers Hauptwerk in der Gattung der Malerei gilt das große Ölgemälde „Viehfütterung" von 1885. Ein breites Publikum erreichte der Künstler mit satirischen Tiergraphiken; die Radierungen, Kranich als „Prediger in der Wüste", „Elephant bei der Toilette" oder „Affen in einem Disput über den von ihrer Sippe ent arteten Menschen", riefen bei jeder öffentlichen Präsentation „das Entzücken der Laien wie der Kenner in gleichem Maße hervor. -

Olga Marickova IS GALICIA a PART of CENTRAL EUROPE?

Серія «Культурологія». Випуск 19 25 УДК 008 Olga Marickova IS GALICIA A PART OF CENTRAL EUROPE? GALICIAN IDENTITY BETWEEN THE WEST AND THE EAST. This article is devoted to the problems o f the cultural identity o f Galicia, because this ethnographic area with a center in Lviv has undergone a com plex historical development, which was reflected both in material-cultural and spiritual-cultural phenomena. Mainly, because Galicia was at the crossroads of the European and Eastern cultures, in view o f the Jewish aspect, during the centuries that affected its identity. Key words: Galicia, Lviv, Central Europe, culture. Мацічкова О. ЧИ Є ГАЛИЧИНА ЧАСТИНОЮ ЦЕНТРАЛЬНОЇ ЄВРОПИ? ГАЛИЦЬКА ІДЕНТИЧНІСТЬ МІЖ ЗАХОДОМ І СХОДОМ. Стаття присвячена проблематиці культурної ідентичності Еаличи- ни, адже ця етнографічна область із центром у Львові зазнала складного історичного розвитку, який відобразився яку матеріально-, так і в духо вно-культурних явищах. Насамперед, тому що впродовж віків Калинина перебувала на перехресті європейських та східних, з оглядом на жидів ський аспект, культур, що позначилося на її ідентичності. Ключові слова: Калинина, Львів, Центральна Європа, культура. Мацичкова О. ЯВЛЯЕТСЯ ЛИ ГАЛИЧИНА ЧАСТЬЮ ЦЕНТРАЛЬНОЙ ЕВРОПЫ? ГАЛИЦКАЯ ИДЕНТИЧНОСТЬ. Статья посвящена проблематике культурной идентичности Кали нины, ведь эта этнографическая область с центром во Львове прошла сложнъш историческим развитием, который проявился как в матери ально-, так в духовно-культурных явлениях. Прежде всего потому, что на протяжении веков Калинина находилась на перекрестке европейских © Olga Macickova, 2018 26 Наукові записки Національного університету «Острозька академія» и восточных, с учётом еврейского аспекта, культур, что сказалось на ее идентичности. Ключевые слова: Галич, Львов, Центральная Европа, культура. Galician issue brings the commotion into the question of concep tion of Central Europe since contemporary Galicia belongs to Ukraine, which is as well as Russia or Belarus one of the Eastern Europe coun tries. -

Pirate Playhouse Sanibel Community 1 88 If B M Association Comedy Night Wednesday

Price leaves Sanibel Arou 'Dinner-set page 3 isEaods burglars strike page 16 JANUARY 7, 1998 VOLUME 26 BER 1 ISLAND LAUGH-IN SET "This proves Harrity and I have been friends since our childhood," H Resignation letter/page 2 tive at the close of the Jan. 5, 1999, says Steve city council meeting," Madison Greenstein. A com- By Gwenda Hiett-Clements wrote. "The past three meetings puter-generated News Editor have resulted in a personal loss of photo of Marty peace and joy, adding unnecessary Harrity and Sanibel City Councilmember stress to our lives. It is wise to Greenstein illus- George Madison resigned his post avoid potential, health-threatening trates Greenstein's Tuesday. Madison, who was serv- activities. In good conscience, I addictive sense of ing the third year of his first term cannot continue to serve on a body humor. He said he on the council, brought his letter of I no longer respect, feeling they talks all of his resignation to the Island Reporter lack integrity and self control." friends into partici- following the council meeting. Madison declined further com- pating in the spe- "I have chosen to resign my seat ment. cial-effects photos on the Sanibel City Council, effec- which were" taken P> See Madison, page 2 in Las Vegas and will do standup comedy along with Walt Hadley at the Pirate Playhouse Sanibel Community 1 88 if B m Association Comedy Night Wednesday. For complete derails and a preview of jokes, please See isSew director hiregl; Zwiclc buys motel page 10. By Jill Goodman wide hunt to replace former director Staff Writer Robert Cacioppo. -

Berlin Period Reports on Albert Einstein's Einstein's FBI File –

Appendix Einstein’s FBI file – reports on Albert Einstein’s Berlin period 322 Appendix German archives are not the only place where Einstein dossiers can be found. Leaving aside other countries, at least one personal dossier exists in the USA: the Einstein File of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).1036 This file holds 1,427 pages. In our context the numerous reports about Ein- stein’s “Berlin period” are of particular interest. Taking a closer look at them does not lead us beyond the scope of this book. On the contrary, these reports give a complex picture of Einstein’s political activities during his Berlin period – albeit from a very specific point of view: the view of the American CIC (Counter Intelligence Corps) and the FBI of the first half of the 1950s. The core of these reports is the allegation that Einstein had cooperated with the communists and that his address (or “office”) had been used from 1929 to 1932 as a relay point for messages by the CPG (Communist Party of Germany, KPD), the Communist International and the Soviet Secret Service. The ultimate aim of these investigations was, reportedly, to revoke Einstein’s United States citizenship and banish him. Space constraints prevent a complete review of the individual reports here. Sounderthegivencircumstancesasurveyofthecontentsofthetwomost im- portant reports will have to suffice for our purposes along with some additional information. These reports are dated 13 March 1950 and 25 January 1951. 13 March 1950 The first comprehensive report by the CIC (Hq. 66th CIC Detachment)1037 about Einstein’s complicity in activities by the CPG and the Soviet Secret Service be- tween 1929 and 1932 is dated 13 March 1950.1038 Army General Staff only submit- ted this letter to the FBI on 7 September 1950. -

“The Double Bind” of 1989: Reinterpreting Space, Place, and Identity in Postcommunist Women’S Literature

“THE DOUBLE BIND” OF 1989: REINTERPRETING SPACE, PLACE, AND IDENTITY IN POSTCOMMUNIST WOMEN’S LITERATURE BY JESSICA LYNN WIENHOLD-BROKISH DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2010 Urbana, Illinois Doctorial Committee: Associate Professor Lilya Kaganovsky, Chair; Director of Research Professor Nancy Blake Professor Harriet Murav Associate Professor Anke Pinkert Abstract This dissertation is a comparative, cross-cultural exploration of identity construction after 1989 as it pertains to narrative setting and the creation of literary place in postcommunist women’s literature. Through spatial analysis the negotiation between the unresolvable bind of a stable national and personal identity and of a flexible transnational identity are discussed. Russian, German, and Croatian writers, specifically Olga Mukhina, Nina Sadur, Monika Maron, Barbara Honigmann, Angela Krauß, Vedrana Rudan, Dubravka Ugrešić, and Slavenka Drakulić, provide the material for an examination of the proliferation of female writers and the potential for recuperative literary techniques after 1989. The project is organized thematically with chapters dedicated to apartments, cities, and foreign lands, focusing on strategies of identity reconstruction after the fall of socialism. ii To My Family, especially Mom, Dad, Jeffrey, and Finnegan iii Table of Contents Chapter One: Introduction: “We are, from this perspective, -

PATRONKA SZKOŁY PODSTAWOWEJ Nr 43 W BIAŁYMSTOKU

SIMONA KOSSAK PATRONKA SZKOŁY PODSTAWOWEJ nr 43 w BIAŁYMSTOKU KLASA 6 D Simona Gabriela Kossak – polska biolożka, profesorka nauk leśnych, popularyzatorka nauki. Znana przede wszystkim z aktywności na rzecz zachowania resztek naturalnych ekosystemów Polski. Pracując naukowo zajmowała się, między innymi, ekologią behawioralną ssaków. Sama siebie określała czasem mianem „zoopsychologa”. Życiorys Simona Gabriela Kossak urodziła się 30 maja 1943 r. w Krakowie, a zmarła 15 marca 2007 r. w Białymstoku. Od 1950 r. uczęszczała do Żeńskiej Szkoły Miejskiej przy ul. Bernardyńskiej 7, a w latach 1957 r.–1961 r. uczyła się w IX Liceum Ogólnokształcącym im. Józefy Joteyko. Po ukończonej maturze zdawała na Wydział Aktorski Państwowej Wyższej Szkoły Teatralnej w Krakowie, nie zdała jednak egzaminu praktycznego, więc wobec tego przystąpiła do egzaminów na Wydział Filologii Polskiej Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego, gdzie została tam przyjęta. W 1962 r. zdawała egzaminy na historię sztuki, ale ponownie nie została przyjęta. W 1963 r. zdawała bezskutecznie egzamin na biologię, a w 1964 r. zdała kolejny egzamin i zwolniwszy się z Instytutu Zootechniki, rozpoczęła studia na Wydziale Biologii i Nauk o Ziemi Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego Życie prywatne Simona urodziła się jako druga córka Elżbiety i Jerzego Kossaka i zamiast stać się czwartym Kossakiem, który zgodnie z rodzinną tradycją kontynuować będzie dziedzictwo i malować konie, budziła tylko rozczarowanie. Była brzydkim kaczątkiem, nie odziedziczyła ani urody po matce, ani talentu malarskiego po przodkach. Gdy Jerzy Kossak tymczasem jej starsza siostra Gloria spełniała wszystkie te ojciec warunki, by zyskać sobie miłość i akceptację rodziców. Wojciech Kossak Juliusz Kossak Gloria Kossak Lech Wilczek -dziadek- -pradziadek- -siostra- -mąż- Pradziadek, dziadek i wspomniany już ojciec Simony byli znanymi malarzami. -

Odessa 2017 UDC 069:801 (477.74) О417 Editorial Board T

GUIDE Odessa 2017 UDC 069:801 (477.74) О417 Editorial board T. Liptuga, G. Zakipnaya, G. Semykina, A. Yavorskaya Authors A. Yavorskaya, G. Semykina, Y. Karakina, G. Zakipnaya, L. Melnichenko, A. Bozhko, L. Liputa, M. Kotelnikova, I. Savrasova English translation O. Voronina Photo Georgiy Isayev, Leonid Sidorsky, Andrei Rafael О417 Одеський літературний музей : Путівник / О. Яворська та ін. Ред. кол. : Т. Ліптуга та ін., – Фото Г. Ісаєва та ін. – Одеса, 2017. – 160 с.: іл. ISBN 978-617-7613-04-5 Odessa Literary Museum: Guide / A.Yavorskaya and others. Editorial: T. Liptuga and others, - Photo by G.Isayev and others. – Odessa, 2017. — 160 p.: Illustrated Guide to the Odessa Literary Museum is a journey of more than two centuries, from the first years of the city’s existence to our days. You will be guided by the writers who were born or lived in Odessa for a while. They created a literary legend about an amazing and unique city that came to life in the exposition of the Odessa Literary Museum UDC 069:801 (477.74) Англійською мовою ISBN 978-617-7613-04-5 © OLM, 2017 INTRODUCTION The creators of the museum considered it their goal The open-air exposition "The Garden of Sculptures" to fill the cultural lacuna artificially created by the ideo- with the adjoining "Odessa Courtyard" was a successful logical policy of the Soviet era. Despite the thirty years continuation of the main exposition of the Odessa Literary since the opening day, the exposition as a whole is quite Museum. The idea and its further implementation belongs he foundation of the Odessa Literary Museum was museum of books and local book printing and the history modern. -

TWEED HEADS NSW Same Size, They Are Allowed to Volunteer Wildlife Carer Live Here’

...and I want a casino, and a mega-mall, and a big plaza on Crown land and a waterfront resort, and, and... Me Me too! too! Me too! Local News Oi! Have ya bought all your Christmas presents yet? Kunghur area cursed, court told If not you better come Luis Feliu and see us An alleged Aboriginal massa- cre more than a century ago has inspired an ongoing curse covering the site of a proposed village in the shadow of Mt Warning. Th e tale of slaughter and the subsequent curse inflicting anyone who settles the site was among one of the more macabre submissions to an onsite court inquiring into the controversial project, attended by around 100 people. Tony and Cathy Ryder, product tester (and lovers) Peter Symons, of Byrill Creek, Hey if you’re stuck for ideas for Christmas presents, we’ll told Land and Environment be able to help you spend your money! Call and see us commissioner, Tim Moore, that at Outdoorism in the main street of Murwillumbah at the elders of the Bunjalung tribes Paris end - you know - where the outdoor cafes are. drew on their verbal history This year we camped on Moreton Island, travelled several years ago to describe through New Zealand on a motor bike, went skiing at to him in detail how events Land and Environment Court commissioner Tim Moore lays down the law to participants and Perisher and had lots more adventures including the unfolded in the rolling river onlookers at the onsite hearing at Kunghur. Variety Trek. We love travelling and the outdoor life and pastures at Kunghur before the we can give you some great advice (maybe we should end of the 19th century.