Moldova David S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jurnalistii 9.Indd

Jurnaliștii contra corupţ iei9 Chişinău, 2014 CZU 328.185(478)(082)=135.1=161.1 J 93 Pictor: Ion Mîţu Această lucrare este editată cu suportul fi nanciar al Fundaţiei Est-Europene, din mijloacele oferite de Guvernul Suediei şi Ministerul Afacerilor Externe al Danemarcei. Opiniile exprimate în ea aparţin autorilor şi nu refl ectă neapărat poziţia Transparency International – Moldova şi a fi nanţatorilor. Difuzare gratuită Descrierea CIP a Camerei Naţionale a Cărţii Jurnaliştii contra corupţiei: [în Rep. Moldova] / Transparency Intern. Moldova; pictor: Ion Mâţu. – Ch.: Transparency Intern. Moldova, 2014 (Tipogr. “Bons Offi ces” SRL). – ISBN 978-9975-80-108-9 [Partea] a 9-a. – 2014. – 280 p. – Text: lb. rom., rusă. ISBN. 978-9975-80-864-4 800 ex. – 1. Jurnalişti – Corupţie – Republica Moldova – Combatere (rom., rusă). Copyright © Transparency International - Moldova, 2014 Transparency International - Moldova Str. „31 August 1989”, nr. 98, of. 205, Chişinău, Republica Moldova, MD-2004 Tel. (373-22) 203484, e-mail: offi [email protected] www.transparency.md ISBN 978-9975-80-108-9 ISBN 978-9975-80-864-4 Cuprins: Cuvânt înainte .................................................................................................... 6 Copiii satului şi afacerile primarului, Tudor Iaşcenco .................................. 7 Imperiul lui Plahotniuc, Mariana Rață........................................................ 11 Interesele avocatului copilului sau pentru cine lucrează Tamara Plămădeală?, Natalia Porubin ..................................................................... 16 Locuinţe ieftine pentru procurori bogaţi, Olga Ceaglei ..............................21 Localitatea Ghidighici, „afacerea” familiei Begleţ, Lilia Zaharia .............. 25 Сага о недоступе к информации, Руслан Михалевский ........................ 27 Cât l-a costat pe Nichifor luxul de la puşcărie?, Iana Zmeu ....................... 33 Averile şi veniturile ascunse ale procurorului Gherasimenco. „El se temea să nu-l afl e lumea că are casă aşa de mare”, Pavel Păduraru .......... -

Gouvernance, Pouvoirs Et Démocratie

CONSEIL DE L’EUROPE Troisième Université d’été de la démocratie 29 juin-4 juillet 2008 Gouvernance, pouvoirs et démocratie SYNTHÈSE DES SESSIONS PLÉNIÈRES ET DES CONFÉRENCES Direction générale de la démocratie et des affaires politiques Conseil de l’Europe, Strasbourg Les vues exprimées dans cet ouvrage sont de la responsabilité de l’auteur et ne reflètent pas nécessairement la ligne officielle du Conseil de l’Europe. Toute demande de reproduction ou de traduction de tout ou d’une partie du document doit être adressée à la Division de l’information publique et des publications, Direction de la communication (F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex ou [email protected]). Toute autre correspondance relative à cette publication doit être adressée à la Direction générale de la démocratie et des affaires politiques. Contacts au Conseil de l’Europe : Jean-Louis Laurens Directeur général de la démocratie et des affaires politiques Courriel : [email protected] Tél. : + 33 (0)3 88 41 20 73 François Friederich Coordinateur des Ecoles d’Etudes Politiques Courriel : [email protected] Tél. : + 33 (03) 90 21 53 02 Claude Bernard Gestionnaire de programme Courriel : [email protected] Tél. : + 33 (03) 88 41 22 75 Site web : www.coe.int www.coe.int/Schools-Politics/fr © Conseil de l’Europe, janvier 2009 Sommaire Introduction : De l’Université d’été au « Davos de la démocratie » ............5 Chapitre I. Démocratie et enjeux de la gouvernance ....................................7 1. Gouvernance, réflexions autour du concept ..........................................................7 2. Composantes de la bonne gouvernance ..............................................................10 3. Les défis de la bonne gouvernance ......................................................................12 Chapitre II. -

Revistă De Ştiinţă, Inovare, Cultură Şi Artă Nr. 1(60) 2021

ISSN 1857-0461 E-SSN 2587-3687 AKADEMOS Revistă de ştiinţă, inovare, cultură şi artă Nr. 1(60) 2021 Fondator: Academia de Științe a Moldovei Înregistrată la Ministerul Justiției la 25.05.2005, nr. 189 Publicație științifică recenzată Categoria „B” Indexată în bazele de date: DOAJ, INDEX COPERNICUS, ISSN, ROAD, GOOGLE SCHOLAR, INFOBASE INDEX, IIJ IMPACT FACTOR © Academia de Ştiinţe a Moldovei Drepturile de autor asupra articolelor publicate aparțin autorilor. Preluarea textelor din revista „Akademos” este posibilă doar cu acordul autorului. Responsabilitatea asupra textului publicat aparţine autorului. Opinia redacţiei nu coincide întotdeauna cu opinia autorului. Pentru publicarea articolelor și recenzarea lor nu se percep taxe. Distribuire gratuită. COLEGIUL DE REDACŢIE: Acad. Ion TIGHINEANU (președintele colegiului), Republica Moldova Acad. Grigore BELOSTECINIC, Republica Moldova Prof. univ., dr. Sorin Mihai CÂMPEANU, România Acad. Mihai CIMPOI, Republica Moldova M. c. Svetlana COJOCARU, Republica Moldova Dr. hab. Liliana CONDRATICOVA, Republica Moldova Prof., dr. Sava COSTIN, Germania Prof., dr. Vladimir FOMIN, Germania Acad. Teodor FURDUI, Republica Moldova Acad. Boris GAINA, Republica Moldova Acad. Asaf HAJIEV, Azerbaidjan Prof., dr. Hidenori MIMURA, Japonia M. c. Victor MORARU, Republica Moldova Acad. Ioan Aurel POP, România Acad. Bogdan C. SIMIONESCU, România Acad. Victor SPINEI, România Prof., dr. Felix UNGER, Austria Dr. hab. Veaceslav URSACHI, Republica Moldova Redactor-șef: Viorica CUCEREANU Concepție grafică: Nicoleta BOGDAN Tehnoredactare: Petru DINU Acest număr este ilustrat cu imagini ale cămășii cu altiță – element de identitate culturală în România și Republica Moldova, propusă pentru înscriere în Lista reprezentativă a patrimoniului cultural imaterial al umanității UNESCO. Fotografii color realizate de dr. Varvara BUZILĂ, membru al Comisiei naționale pentru salvgardarea patrimoniului cultural imaterial. -

Opinia Separată a Judecătorului Constituţional

Victor PUŞCAŞ Valeriu KUCIUK OPINIA SEPARATĂ A JUDECĂTORULUI CONSTITUŢIONAL Sinteză de jurisprudenţă constituţională cu comentarii (23.02.2001-23.02.2013) „Opinia separată a judecătorului constituțional, este un indicator al independenţei şi responsabilităţii” Victor PUȘCAȘ Lucrarea a fost aprobată şi recomandată pentru editare de Consiliul ştiinţific al Asociaţiei Obşteşti „Congresul Democraţiei Constituţionale” (Procesul-verbal nr.7 din 20.11.2020) Autori: Victor PUŞCAŞ, Doctor în drept, Conferenţiar universitar, Ex-preşedinte al Curţii Constituţionale a Republicii Moldova Valeriu KUCIUK, Doctor în drept, Lector universitar, Avocat. Monografia „OPINIA SEPARATĂ a JUDECĂTORULUI CONSTITUŢIONAL: indicator al independenţei şi responsabilităţii” este o sinteză de jurisprudenţă constituţională strict întemeiată pe studiu de caz comentat. Lucrarea poate servi sursă de cercetare, dar şi călăuză/îndrumar practic, inclusiv pentru studenţi şi cercetători a dreptului constituţional din Republica Moldova. Descrierea CIP a Camerei Naţionale a Cărţii © Victor PUŞCAŞ, Doctor în drept, Conferenţiar universitar © Valeriu KUCIUK, Doctor în drept, Lector universitar Toate drepturile asupra prezentei ediţii aparţin autorilor. Nici o parte din acest volum nu poate fi copiată sau reprodusă fără acordul scris al autorilor. CUPRINS DEDICAȚIE ȘI MULȚUMIRI ......................................................................10 CUVÎNT ÎNAINTE ........................................................................................11 Scrisoare – felicitare de la -

Honouring of Obligations and Commitments by the Republic of Moldova

AS/Mon(2012)03 rev 14 March 2012 amondoc03r_2012 or. Engl. Committee on the Honouring of Obligations and Commitments by Member States of the Council of Europe (Monitoring Committee) Honouring of obligations and commitments by the Republic of Moldova Information note by the co-rapporteurs on their fact-finding visit to Chisinau (28 November – 1 December 2011) 1 Co-rapporteurs: Ms Lise CHRISTOFFERSEN, Norway, Socialist group, and Mr Piotr WACH, Poland, Group of the European People’s Party 1 This information note has been made public by decision of the Monitoring Committee dated 13 March 2012. F – 67075 Strasbourg Cedex | e-mail: [email protected] | Tel: + 33 3 88 41 2000 | Fax: +33 3 88 41 2733 AS/Mon(2012)03rev I. Introduction 1. After a first visit to Chisinau and Comrat in March 2011 (see doc. AS/Mon (2011) 13 rev), we paid a second fact-finding visit to the Republic of Moldova from 28 November to 1 December 2011. The programme of the visit is appended. We intended to address the implementation of Resolution 1572 (2007) on The honouring of obligations and commitments by Moldova, Resolutions 1666 (2009) and 1692 (2009) on The functioning of democratic institutions , the state of play of the election of the President of the Republic, and other current issues, such as the reform of the judiciary, the action taken to combat corruption and organised crime, the legislation and measures to combat discrimination and the latest developments in Transnistria. 2. The support of the Moldovan delegation to the PACE, the Moldovan parliament, and Mr Ulvi Akhundlu, Head of the Council of Europe Office in Chisinau, was again precious for facilitating our meetings, including with the acting President and Speaker, Mr Marian Lupu, the Prime Minister, Mr Filat, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Mr Leanca, the Vice-Speaker of the parliament, Mr Plahotniuc, high-level representatives of the judiciary and enforcement bodies, representatives of the media and NGOs. -

Hristos a Înviat!

Nr. 8 (357) FUNCŢIONARUL aprilieHRISTOS8 2011 Martie - Ziua Interna�ional� A ÎNVIAT! a FemeiiPUBLIC NR.Nr. 8 5(357) (354) aprilie martie 2011 2011 FONDATFONDAT �N ANUL ÎN ANUL 1994 1994 ZIARZIAR BILUNAR BILUNAR EDITAT EDITAT DE DE CÃTRE CĂTRE ACADEMIA ACADEMIA DE DE ADMINISTRARE ADMINISTRARE PUBLICÃ PUBLICĂ DEDE PEPE LÂNGÃLÂNGĂ PREªEDINTELEPREŞEDINTELE REPUBLICII REPUBLICII MOLDOVA MOLDOVA SUPLIMENT LA REVISTA “ADMINISTRAREA PUBLICĂ“ ei BUCURIAFelicitare �I pascală DRAGOSTEA S� Fie ca aceast� Colectivului V� profesoral-didactic, INUNDE tuturor colaboratorilor SUFLETUL Aca- prim�var� s� v� demiei de Administrare PublicăS t ide m pe a lângă t e Preşedintelefeminin. Ideea, Republi cã -ºi lupta ºi pâinea, sunt aduc� g�nduri cii Moldova colege, dragi tot de genul feminin. Privindu-vã pe D- femei, D-voastră şi familiilorvoastrã, D-voastră femeile, cele sfârºeºti a crede în mitul curate V ã rmai o g cordiale s ã felicităricu supraoameni şi sincere urări în care fiecare dintre femei acceptaþide bine în şi succesvaloreazã cu prilejul cât Sfintelor doi bãrbaþi. Ambiþioase, �i senine n u m e l e dinamice, cu plãcerea muncii, emotive ºi Cu ocazia Senatuluisărbători ºi al de Paşti,eficace, a Învierii D-voastrã Domnu- faceþi ca actul de sãrbãtorii de 8 Rectoratuluilui nostru Isusintervenþie Hristos. sã fie mai intuitiv, mai Martie, adresez AcademieiFie de ca Luminapsihologic, Divină a maiSfintelor benefic. tuturor femeilor Administraresărbători de PaştiNu să existã Vă aducă prilej tot ce mai minunat de dãruire de la Academia de Publicãpoate de pefi maipentru bun pe lume, D-voastrã, linişte în cadre profesoral- Administrare suflet, multă bucurie, sănătate, feri- Publicã de pe l â ncire g şi puterea ã didactice de a dărui ale şi Academiei,a ajuta decât sã puteþi da, Preºedintele Republicii Moldova, precum zi de zi, tot ce aveþi mai bun din D-voastrã, l â n g ã semenii. -

Public Opinion Survey Residents of Moldova

Public Opinion Survey Residents of Moldova September 2016 Detailed Methodology • The survey was coordinated by Dr. Rasa Ališauskienė from the public opinion and market research company, Baltic Surveys/The Gallup Organization on behalf of the International Republican Institute. The field work was carried out by Magenta Consulting. • Data was collected throughout Moldova (with the exception of Transnistria) between September 1–23, 2016 through face- to-face interviews at respondents’ homes. • The main sample consisted of 1,516 permanent residents of Moldova older than the age of 18 and eligible to vote. The survey also contained an oversample in the capital of Chisinau. It is representative of the general population by age, gender, education, region and size of the settlement. • Multistage probability sampling method was used with the random route and next birthday respondent’s selection procedures. • Stage One: All districts of Moldova are grouped into 11 groups. All regions of Moldova were surveyed. • Stage Two: Selection of the settlements – cities and villages. o Settlements were selected at random. o The number of selected settlements in each region was proportional to the share of population living in a particular type of the settlement in each region. • Stage Three: Primary sampling units were described. • The margin of error does not exceed plus or minus 2.8 percent. • The response rate was 61 percent. • Charts and graphs may not add up to 100 percent due to rounding. • The survey was funded by the National Endowment for Democracy. -

Final Report, Ijc, May 1

Monitoring Mass Media during the Campaign for Local General Elections on 14 June 2015 Final Report 1 May–14 June 2015 This report was produced by the Independent Journalism Center with the financial support of the East European Foundation from funds granted by the Swedish International Development and Cooperation Agency (Sida/Asdi) and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark/DANIDA. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the points of view of the East European Foundation, the Government of Sweden, Sida or of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark/DANIDA. 3. Monitoring Data Involvement in the campaign From 1 May to 14 June 2015, public TV station Moldova 1 actively covered the campaign: It aired 185 items that directly or indirectly covered the elections. Some of them directly covered the campaign including the activities of the Central Electoral Commission (CEC) and the activities of the candidates but also problems at city hall in the capital or at some ministries and public servants. Among the news items that indirectly covered the elections were the ones about the allowances granted to WWII veterans, the new trolleybuses to be in operation by the end of 2015, renovations to several national roads, and the negotiations with farmers and solutions offered by Parliament, among others. Objectivity and impartiality/political partisanship During this monitoring period, the relevant new items broadcast by Moldova 1 had no deviations from journalistic norms that could distort the information provided to the public. Of the of 175 news items with a direct or indirect electoral content, most presented objective and unbiased information. -

Stenograma) Sumar 1

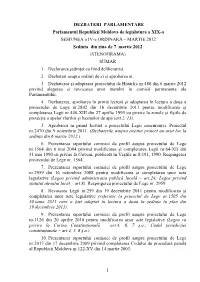

DEZBATERI PARLAMENTARE Parlamentul Republicii Moldova de legislatura a XIX-a SESIUNEA a IV-a ORDINARĂ – MARTIE 2012 Ședința din ziua de 7 martie 2012 (STENOGRAMA) SUMAR 1. Declararea ședinței ca fiind deliberativă. 2. Dezbateri asupra ordinii de zi și aprobarea ei. 3. Dezbaterea și adoptarea proiectului de Hotărîre nr.480 din 6 martie 2012 privind alegerea și revocarea unor membri în comisii permanente ale Parlamentului. 4. Dezbaterea, aprobarea în primă lectură și adoptarea în lectura a doua a proiectului de Lege nr.2802 din 16 decembrie 2011 pentru modificarea şi completarea Legii nr.440-XIII din 27 aprilie 1995 cu privire la zonele şi fîşiile de protecţie a apelor rîurilor şi bazinelor de apă (art.2, 13). 5. Aprobarea în primă lectură a proiectului Legii concurenţei. Proiectul nr.2470 din 9 noiembrie 2011. (Dezbaterile asupra acestui proiect au avut loc la ședința din 6 martie 2012.) 6. Prezentarea raportului comisiei de profil asupra proiectului de Lege nr.1564 din 6 mai 2004 privind modificarea şi completarea Legii nr.64-XII din 31 mai 1990 cu privire la Guvern, publicată în Veştile nr.8/191, 1990. Respingerea proiectului de Lege nr. 1564. 7. Prezentarea raportului comisiei de profil asupra proiectului de Lege nr.2959 din 16 octombrie 2008 pentru modificarea şi completarea unor acte legislative (Legea privind administraţia publică locală – art.24; Legea privind statutul alesului local – art.8). Respingerea proiectului de Lege nr. 2959. 8. Revotarea Legii nr.259 din 19 decembrie 2011 pentru modificarea şi completarea unor acte legislative (referitor la proiectul de Lege nr.1505 din 30 iunie 2011 care a fost adoptat în lectura a doua la ședința în plen din 19 decembrie 2011). -

Promoting Government Accountability in Moldova

Promoting Government Accountability in Moldova A project supported by the National Endowment for Democracy and implemented by Business News Service /Mold-Street.com during 1 May 2017 - 31 May 2018 The version in English 1 Project coordinator: Eugeniu Rîbca All rights reserved Mold-Street.com © 2 Instead of Pay Raise, Government Prepares Pay Optimization in Public Area Public sector employees – especially in the education area – continue to nourish hopes for a perceptible pay raise. This expectation however is unlikely this year, because the salary bill for teachers and lecturers is al- ready too expensive, the Government says. Earlier protests with education employees forced the Govern- ment to pass a number of decisions regarding the remuneration improvements. One of decisions envisages a salary increase for education staff in public institutions and for other employees based on the Common Tar- iff Network. Pay raise promises Starting May 1, 2017, the public education staff in Moldova will receive a monthly raise of 100 lei (5$) and from September they will get a 10% raise, the Labor and Social Protection Ministry announced. At the same time, current legislation and the 2016 economic performance would allow to raise teachers’ salaries by 5.3% while the Government would be looking for additional funding during the amendment of the 2017 budget. On the other hand, the Government admits in the Additional Memorandum on Economic and Financial Poli- cies with the IMF that it is short of resources to increases the public spending, including salaries. Salary expenses are “too large” "On the expense side the salary expenses in the public sector exceed the targets that have been established in the Memorandum with the International Monetary Fund which was signed on October 24, 2016," the execu- tive said in a press release. -

Raport 1, Ccalc, 1-17 Octombrie 2014

Monitorizarea mass-media în campania electorală pentru alegerile parlamentare 2014 Televiziuni. Raportul nr. 1 Perioada: 01 – 17 octombrie 2014 Proiectul de monitorizare a mass-media este realizat de către CJI, APEL și API în cadrul Coaliției Civice pentru Alegeri Libere și Corecte și este finanţat de National Endowment for Democracy (SUA), Ambasada SUA în Republica Moldova şi Fundaţia Est-Europeană (din resursele acordate de Guvernul Suediei prin intermediul Agenţiei Suedeze pentru Dezvoltare şi Cooperare Internaţională (Sida) și Ministerul Afacerilor Externe al Danemarcei/DANIDA). Opiniile exprimate aparţin autorilor şi nu reflectă neapărat punctul de vedere al finanţatorilor. 1 | Acest raport a fost realizat de Asociația Presei Electronice cu sprijinul Ambasadei Statelor Unite în Republica Moldova I. Date generale 1.1 Obiectivul proiectului: monitorizarea şi informarea opiniei publice privind comportamentul editorial al instituţiilor mass-media în perioada electorală pentru alegerile parlamentare din Republica Moldova. 1.2 Perioada de monitorizare: 1 octombrie 2014 – 30 noiembrie 2014. 1.3 Criteriile de selectare a instituţiilor mass-media supuse monitorizării: Instituțiile mass-media au fost selectate în baza următoarelor criterii obiective: a) forma de proprietate; b) geografie; c) limba de difuzare. Astfel, printre acestea sunt instituții mass-media publice și private, cu acoperire națională, cvasi-națională și regională, în limba română și în limba rusă. 1.4 Televiziuni monitorizate (în ordine alfabetică): 1. Accent TV 2. Canal 2 3. Canal 3 4. Canal Regional 5. GRT 6. Jurnal TV 7. Moldova 1 8. N4 9. Prime TV 10. ProTV Chişinău 11. TV7 12. Publika TV 1.5 Obiectul monitorizării A. ştirile cu caracter electoral din principala ediţie informativă a zilei; B. -

Raport 3, Promo-LEX, 9-22 Ianuarie 2019

RAPORTUL nr. 3 Misiunea de Observare a Alegerilor parlamentare din 24 februarie 2019 Perioada de monitorizare: 9 ianuarie – 22 ianuarie 2019 Publicat la 24 ianuarie 2019 Chișinău 2019 Toate drepturile sunt protejate. Conținutul Raportului poate fi utilizat și reprodus în scopuri non–profit și fără acordul prealabil al Asociației Promo–LEX, cu condiția indicării sursei de informație. Conținutul raportului poate fi supus revizuirilor redacționale. Raportul este elaborat în cadrul Misiunii de Observare a Alegerilor parlamentare din 24 februarie 2019 desfășurată de Asociația Promo-LEX cu suportul financiar al Agenției Statelor Unite pentru Dezvoltare Internațională (USAID) prin Programul “Democrație, Transparență și Responsabilitate”; a Ambasadei Marii Britanii la Chișinău prin proiectul „Consolidarea responsabilității democratice în Moldova”; a Fundației Soros-Moldova prin proiectele „Consolidarea unei platforme de dezvoltare a activismului și educației de Drepturi ale Omului în Republica Moldova” și „Monitorizarea listelor de alegători și a litigiilor electorale în alegerile parlamentare din 2018”; a Consiliului Europei prin proiectul “Suport pentru monitorizarea alegerilor parlamentare din 2018”. Acest raport conține informații și date expuse pentru perioada 9 ianuarie - 22 ianuarie 2019 colectate si prezentare de MO Promo-LEX. Conținutul acestui document poate fi supus revizuirilor redacționale. Responsabilitatea pentru opiniile exprimate în cadrul acestui raport aparține Asociației Promo-LEX și nu reflectă neapărat poziția donatorilor.