Moldovan Institute for Human Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Continuitate Și Discontinuitate În Reformarea Organizării Teritoriale a Puterii Locale Din Republica Moldova Cornea, Sergiu

www.ssoar.info Continuitate și discontinuitate în reformarea organizării teritoriale a puterii locale din Republica Moldova Cornea, Sergiu Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Sammelwerksbeitrag / collection article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Cornea, S. (2018). Continuitate și discontinuitate în reformarea organizării teritoriale a puterii locale din Republica Moldova. In C. Manolache (Ed.), Reconstituiri Istorice: civilizație, valori, paradigme, personalități: In Honorem academician Valeriu Pasat (pp. 504-546). Chișinău: Biblioteca Științifică "A.Lupan". https://nbn-resolving.org/ urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-65461-2 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC Lizenz (Namensnennung- This document is made available under a CC BY-NC Licence Nicht-kommerziell) zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu (Attribution-NonCommercial). For more Information see: den CC-Lizenzen finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/deed.de MINISTERUL EDUCAȚIEI, CULTURII ȘI CERCETĂRII AL REPUBLICII MOLDOVA MINISTERUL EDUCAȚIEI, CULTURII ȘI CERCETĂRII AL REPUBLICII MOLDOVA INSTITUTUL DE ISTORIE INSTITUTUL DE ISTORIE BIBLIOTECA LUPAN” BIBLIOTECA LUPAN” Biblioteca Științică Biblioteca Științică Secția editorial-poligracă Secția editorial-poligracă Chișinău, 2018 Chișinău, 2018 Lucrarea a fost discutată și recomandată pentru editare la şedinţa Consiliului ştiinţific al Institutului de Istorie, proces-verbal nr. 8 din 20 noiembrie 2018 şi la şedinţa Consiliului ştiinţific al Bibliotecii Științifice (Institut) „Andrei Lupan”, proces-verbal nr. 16 din 6 noiembrie 2018 Editor: dr. hab. în științe politice Constantin Manolache Coordonatori: dr. hab. în istorie Gheorghe Cojocaru, dr. hab. în istorie Nicolae Enciu Responsabili de ediție: dr. în istorie Ion Valer Xenofontov, dr. în istorie Silvia Corlăteanu-Granciuc Redactori: Vlad Pohilă, dr. -

Moldova: from Oligarchic Pluralism to Plahotniuc's Hegemony

Centre for Eastern Studies NUMBER 208 | 07.04.2016 www.osw.waw.pl Moldova: from oligarchic pluralism to Plahotniuc’s hegemony Kamil Całus Moldova’s political system took shape due to the six-year rule of the Alliance for European Integration coalition but it has undergone a major transformation over the past six months. Resorting to skilful political manoeuvring and capitalising on his control over the Moldovan judiciary system, Vlad Plahotniuc, one of the leaders of the nominally pro-European Democra- tic Party and the richest person in the country, was able to bring about the arrest of his main political competitor, the former prime minister Vlad Filat, in October 2015. Then he pushed through the nomination of his trusted aide, Pavel Filip, for prime minister. In effect, Plahot- niuc has concentrated political and business influence in his own hands on a scale unseen so far in Moldova’s history since 1991. All this indicates that he already not only controls the judi- ciary, the anti-corruption institutions, the Constitutional Court and the economic structures, but has also subordinated the greater part of parliament and is rapidly tightening his grip on the section of the state apparatus which until recently was influenced by Filat. Plahotniuc, whose power and position depends directly on his control of the state apparatus and financial flows in Moldova, is not interested in a structural transformation of the country or in implementing any thorough reforms; this includes the Association Agreement with the EU. This means that as his significance grows, the symbolic actions so far taken with the aim of a structural transformation of the country will become even more superficial. -

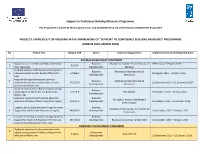

Projects Carried out Or Ongoing in the Framework of "Support to Confidence Building Measures" Programme (March 2015- March 2018)

Support to Confidence Building Measures Programme This Programme is funded by the European Union, and implemented by the United Nations Development Programme PROJECTS CARRIED OUT OR ONGOING IN THE FRAMEWORK OF "SUPPORT TO CONFIDENCE BUILDING MEASURES" PROGRAMME (MARCH 2015- MARCH 2018) No Project title Budget, EUR Sector Implementing partners Implementation period/Expected dates BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT COMPONENT Support to a set of CSOs and BAs and develop Business Chamber of Commerce and Industry of 29 February – 29 April, 2016 1 9,314 € their capacities Development Moldova In-depth analysis of the Business Development Business Alternative Internationale de 2 Services market on both banks of the Nistru 67,568 € 18 August, 2015 – 29 April, 2016 Development Dezvoltare river Improve the opportunities and services 3 Business Alternative Internationale de available for business communities on both 172,725 € 21 December 2015 – 21 December 2017 Development Dezvoltare banks of the Nistru river Study on entrepreneurship perception among Business 4 youth (aged 18-35) on the left bank of the 22,519 € CBS-AXA SRL 20 October, 2015 – 20 May, 2016 Development Nistru river Economic research and forecasts about the Business AO Centrul Analitic Independent 5 economic situation of the Transnistrian region 60,011 € Development 15 October, 2015 – 15 October, 2016 EXPERT-GRUP Creation of Job Opportunities through Business Business Chamber of Commerce and Industry of 6 Support for Youth in the Transnistria region 344,561 € Development 1 September, 2015 – 30 April, -

Jurnalistii 9.Indd

Jurnaliștii contra corupţ iei9 Chişinău, 2014 CZU 328.185(478)(082)=135.1=161.1 J 93 Pictor: Ion Mîţu Această lucrare este editată cu suportul fi nanciar al Fundaţiei Est-Europene, din mijloacele oferite de Guvernul Suediei şi Ministerul Afacerilor Externe al Danemarcei. Opiniile exprimate în ea aparţin autorilor şi nu refl ectă neapărat poziţia Transparency International – Moldova şi a fi nanţatorilor. Difuzare gratuită Descrierea CIP a Camerei Naţionale a Cărţii Jurnaliştii contra corupţiei: [în Rep. Moldova] / Transparency Intern. Moldova; pictor: Ion Mâţu. – Ch.: Transparency Intern. Moldova, 2014 (Tipogr. “Bons Offi ces” SRL). – ISBN 978-9975-80-108-9 [Partea] a 9-a. – 2014. – 280 p. – Text: lb. rom., rusă. ISBN. 978-9975-80-864-4 800 ex. – 1. Jurnalişti – Corupţie – Republica Moldova – Combatere (rom., rusă). Copyright © Transparency International - Moldova, 2014 Transparency International - Moldova Str. „31 August 1989”, nr. 98, of. 205, Chişinău, Republica Moldova, MD-2004 Tel. (373-22) 203484, e-mail: offi [email protected] www.transparency.md ISBN 978-9975-80-108-9 ISBN 978-9975-80-864-4 Cuprins: Cuvânt înainte .................................................................................................... 6 Copiii satului şi afacerile primarului, Tudor Iaşcenco .................................. 7 Imperiul lui Plahotniuc, Mariana Rață........................................................ 11 Interesele avocatului copilului sau pentru cine lucrează Tamara Plămădeală?, Natalia Porubin ..................................................................... 16 Locuinţe ieftine pentru procurori bogaţi, Olga Ceaglei ..............................21 Localitatea Ghidighici, „afacerea” familiei Begleţ, Lilia Zaharia .............. 25 Сага о недоступе к информации, Руслан Михалевский ........................ 27 Cât l-a costat pe Nichifor luxul de la puşcărie?, Iana Zmeu ....................... 33 Averile şi veniturile ascunse ale procurorului Gherasimenco. „El se temea să nu-l afl e lumea că are casă aşa de mare”, Pavel Păduraru .......... -

Report on Research Into the Process of Transition from Kindergarten to School

Ensuring Educational Inclusion for Children with Special Educational Needs Report on Research into the Process of Transition from Kindergarten to School Chisinau, 2015 1 Contents Abbreviations and acronymns ................................ ................................ .................... 2 1. Introduction ................................ ................................ ................................ .......... 3 1.1. Background to the research ................................ ................................ ............. 3 1.2. Background to the context ................................ ................................ ............... 5 2. Findings ................................ ................................ ................................ ................ 6 2.1. Attitudes towards inclusive education ................................ .............................. 6 2.2. Teaching and learning practices ................................ ................................ ...... 7 2.3. Parents’ roles and expectations ................................ ................................ ....... 8 2.4. Communication issues ................................ ................................ ................... 11 2.5. Specialist support ................................ ................................ .......................... 11 2.6. Suggestions from respondents to make transition more inclusive ................. 12 3. Conclusions ................................ ................................ ................................ ....... -

External Evaluation of OHCHR Project “Combating Discrimination in the Republic of Moldova, Including in the Transnistrian Region” 2014-2015

External Evaluation of OHCHR Project “Combating Discrimination in the Republic of Moldova, including in the Transnistrian Region” 2014-2015 FINAL REPORT This report has been prepared by an external consultant. The views expressed herein are those of the consultant and therefore do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the OHCHR. December 2015 Acknowledgments The evaluator of the OHCHR project “Combating Discrimination in the Republic of Moldova, including in the Transnistrian Region” is deeply grateful to the many individuals who made their time available for providing information, discussing and answering questions. In particular, the evaluator benefited extensively from the generous information and feedback from OHCHR colleagues and consultants in OHCHR Field Presence in Moldova and in OHCHR Geneva. The evaluator also had constructive meetings with groups of direct beneficiaries, associated project partners, national authorities, and UN colleagues in Moldova, including in the Transnistrian region. External Evaluator Mr. Bjorn Pettersson, Independent Consultant OHCHR Evaluation Reference Group Mrs. Jennifer Worrell (PPMES) Mrs. Sylta Georgiadis (PPMES) Mr. Sabas Monroy (PPMES) Mrs. Hulan Tsedev (FOTCD) Ms. Anita Trimaylova (FOTCD) Ms. Laure Beloin (DEXREL) Mr. Ferran Lloveras (OHCHR Brussels) Table of Contents Table of Contents ......................................................................................................................................... 3 List of Abbreviations .................................................................................................................................... -

2016 Human Rights Report

MOLDOVA 2016 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT Note: Unless otherwise noted, all references in this report exclude the secessionist region of Transnistria. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Moldova is a republic with a form of parliamentary democracy. The constitution provides for a multiparty democracy with legislative and executive branches as well as an independent judiciary and a clear separation of powers. Legislative authority is vested in the unicameral parliament. Pro-European parties retained a parliamentary majority in 2014 elections that met most Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), Council of Europe, and other international commitments, although local and international observers raised concerns about the inclusion and exclusion of specific political parties. On January 20, a new government was formed after two failed attempts to nominate a candidate for prime minister. Opposition and civil society representatives criticized the government formation process as nontransparent. On March 4, the Constitutional Court ruled unconstitutional an amendment that empowered parliament to elect the president and reinstated presidential elections by direct and secret popular vote. Two rounds of presidential elections were held on October 30 and November 13, resulting in the election of Igor Dodon. According to the preliminary conclusions of the OSCE election observation mission, both rounds were fair and respected fundamental freedoms. International and domestic observers, however, noted polarized and unbalanced media coverage, harsh and intolerant rhetoric, lack of transparency in campaign financing, and instances of abuse of administrative resources. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the security forces. Widespread corruption, especially within the judicial sector, continued to be the most significant human rights problem during the year. -

Studia Politica 1 2016

www.ssoar.info Republic of Moldova: the year 2015 in politics Goșu, Armand Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Goșu, A. (2016). Republic of Moldova: the year 2015 in politics. Studia Politica: Romanian Political Science Review, 16(1), 21-51. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-51666-3 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de Republic of Moldova The Year 2015 in Politics ARMAND GO ȘU Nothing will be the same from now on. 2015 is not only a lost, failed year, it is a loop in which Moldova is stuck without hope. It is the year of the “theft of the century”, the defrauding of three banks, the Savings Bank, Unibank, and the Social Bank, a theft totaling one billion dollars, under the benevolent gaze of the National Bank, the Ministry of Finance, the General Prosecutor's Office, the National Anti-Corruption Council, and the Security and Intelligence Service (SIS). 2015 was the year when controversial oligarch Vlad Plakhotniuk became Moldova's international brand, identified by more and more chancelleries as a source of evil 1. But 2015 is also the year of budding hope that civil society is awakening, that the political scene is evolving not only for the worse, but for the better too, that in the public square untarnished personalities would appear, new and charismatic figures around which one could build an alternative to the present political parties. -

Lista Filialelor/Oficiilor Secundare Ale BC"MOLDOVA-AGROINDBANK"S.A., Conform Situatiei La 30.09.2017 Nr

Lista filialelor/oficiilor secundare ale BC"MOLDOVA-AGROINDBANK"S.A., conform situatiei la 30.09.2017 nr. Denumirea Cod Adresa Telefon d/o Filiala nr.6 Chişinău a Băncii comerciale 1 413 MD-2071, mun. Chişinău, str. Alba-Iulia, 184/3 22 501617 ”MOLDOVA-AGROINDBANK”S.A. Agenţia nr.1 a filialei nr.6 Chişinău a Băncii 2 MD-2008, mun. Chişinău, str. V. Lupu, 18 22 303815 comerciale „MOLDOVA-AGROINDBANK”S.A. Filiala nr.7 Chişinău a Băncii comerciale 3 415 MD-2012, mun. Chişinău, str. Eminescu Mihai, 63 22 245506 ”MOLDOVA-AGROINDBANK”S.A. Filiala nr.9 Chişinău a Băncii comerciale 4 434 MD-2015, mun. Chişinău, Decebal bd., 23 22 503435 ”MOLDOVA-AGROINDBANK”S.A. Filiala nr.5 Chişinău a Băncii comerciale 5 435 MD-2044, mun. Chişinău, str. Russo Alecu, 63/6 22 402030 ”MOLDOVA-AGROINDBANK”S.A. Agenţia nr.1 a Filialei nr.5 Chişinău a Băncii MD-2044, mun. Chişinău, str. Meşterul Manole, 6 22 923250 comerciale ”MOLDOVA-AGROINDBANK”S.A. 14/1 Agenţia nr.2 a Filialei nr.5 Chişinău a Băncii 421200 7 MD-2044, mun. Chişinău, str. Maria Dragan, 1/1 22 comerciale ”MOLDOVA-AGROINDBANK”S.A. 421213 Agenţia nr.3 a filialei nr.5 Chişinău a Băncii 8 MD-2023, mun. Chișinău, str. Industrială, 73 22 428745 comerciale „MOLDOVA-AGROINDBANK”S.A. Filiala nr.10 Chişinău a Băncii comerciale 9 437 MD-2068, mun. Chişinău, bd. Moscova, 5 22 497744 ”MOLDOVA-AGROINDBANK”S.A. Agenţia nr.1 a Filialei nr.10 Chişinău a Băncii 10 MD-2068, mun. Chişinău, str. -

The Impact of the European Court of Human Rights on Justice Sector Reform in the Republic of Moldova

Journal of Liberty and International Affairs | Vol. 4, No. 2, 2018 | eISSN 1857-9760 Published online by the Institute for Research and European Studies at www.e-jlia.com © 2018 Judithanne Scourfield McLauchlan This is an open access article distributed under the CC-BY 3.0 License. Peer review method: Double-Blind Date of acceptance: September 16, 2018 Date of publication: November 12, 2018 Original scientific article UDC 341.645.544.096(478) THE IMPACT OF THE EUROPEAN COURT OF HUMAN RIGHTS ON JUSTICE SECTOR REFORM IN THE REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA Judithanne Scourfield McLauchlan Associate Professor of Political Science, University of South Florida St. Petersburg, United States of America Fulbright Scholar Moldova 2010, 2012 jsm2[at]usfsp.edu Abstract For this study, I reviewed the judgments of the European Court of Human Rights against the Republic of Moldova and the corresponding reports of the Committee of Ministers from 1997 through 2014. In addition, I interviewed more than 25 lawyers, judges, and human rights advocates. After analyzing the effectiveness of the Court in terms of compliance with the judgments in specific cases (individual measures), I will assess the broader impact of these decisions (general measures) on legal reforms and public policy in the Republic of Moldova. I will evaluate the effectiveness of the decisions of the ECtHR in the context of the implementation of Moldova’s Justice Sector Reform Strategy (2011-2015), the Council of Europe’s Action Plan to Support Democratic Reforms in the Republic of Moldova (2013-2016), and Moldova’s National Human Rights Action Plan (2011-2014). My findings will offer insights into the constraints faced by the ECtHR in implementing its decisions and the impact of the ECtHR on national legal systems. -

Rapid Assessment of Trafficking in Children for Labour and Sexual Exploitation in Moldova

PROject of Technical assistance against the Labour and Sexual Exploitation of Children, including Trafficking, in countries of Central and Eastern Europe PROTECT CEE www.ilo.org/childlabour International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC) International Labour Office 4, Route des Morillons CH 1211 Geneva 22 Switzerland Rapid Assessment of Trafficking E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (+41 22) 799 81 81 in Children for Labour and Sexual Fax: (+41 22) 799 87 71 Exploitation in Moldova ILO-IPEC PROTECT CEE ROMANIA intr. Cristian popisteanu nr. 1-3, Intrarea D, et. 5, cam. 574, Sector 1, 010024-Bucharest, ROMANIA [email protected] Tel: +40 21 313 29 65 Fax: +40 21 312 52 72 2003 ISBN 92-2-116201-X IPEC International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour Rapid Assessment of Trafficking in Children for Labour and Sexual Exploitation in Moldova Prepared by the Institute for Public Policy, Moldova Under technical supervision of FAFO Institute for Applied International Studies, Norway for the International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC) of the International Labour Organization (ILO) Chisinau, 2003 Copyright © International Labour Organization 2004 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to the ILO Publications Bureau (Rights and Permissions), -

STUDY Finance Benchmarks: Areas and Options for Assessing Local Financial Resources and Financial Management in Moldova

STRENGTHENING INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORKS FOR LOCAL GOVERNANCE PROGRAMME 2015-2017 STUDY Finance Benchmarks: areas and options for assessing local financial resources and financial management in Moldova Author: Viorel Roscovan September 25, 2015 Table of contents 1. POLITICAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE STRUCTURE OF THE REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA ....... 5 1.1. GENERAL DATA ...................................................................................................................................... 5 1.2. ADMINISTRATIVE-TERRITORIAL DIVISION AND LOCAL GOVERNMENTS .................................................. 5 1.3. POLITICAL STRUCTURE ........................................................................................................................... 6 2. LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMPETENCES ........................................................................................... 7 2.1. LOCAL GOVERNMENT FUNCTIONS, RESPONSIBILITIES, AND RIGHTS ........................................................ 7 2.2. INSTITUTIONAL STRUCTURE OF LOCAL GOVERNMENTS .......................................................................... 9 2.3. LOCAL GOVERNMENTS SUPERVISION .................................................................................................... 11 3. LOCAL GOVERNMENT OWN AND SHARED REVENUES ............................................................ 12 3.1. OWN REVENUES ................................................................................................................................... 13 3.2. SHARED TAXES AND FEES