STUDY Finance Benchmarks: Areas and Options for Assessing Local Financial Resources and Financial Management in Moldova

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

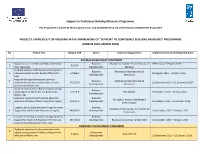

Projects Carried out Or Ongoing in the Framework of "Support to Confidence Building Measures" Programme (March 2015- March 2018)

Support to Confidence Building Measures Programme This Programme is funded by the European Union, and implemented by the United Nations Development Programme PROJECTS CARRIED OUT OR ONGOING IN THE FRAMEWORK OF "SUPPORT TO CONFIDENCE BUILDING MEASURES" PROGRAMME (MARCH 2015- MARCH 2018) No Project title Budget, EUR Sector Implementing partners Implementation period/Expected dates BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT COMPONENT Support to a set of CSOs and BAs and develop Business Chamber of Commerce and Industry of 29 February – 29 April, 2016 1 9,314 € their capacities Development Moldova In-depth analysis of the Business Development Business Alternative Internationale de 2 Services market on both banks of the Nistru 67,568 € 18 August, 2015 – 29 April, 2016 Development Dezvoltare river Improve the opportunities and services 3 Business Alternative Internationale de available for business communities on both 172,725 € 21 December 2015 – 21 December 2017 Development Dezvoltare banks of the Nistru river Study on entrepreneurship perception among Business 4 youth (aged 18-35) on the left bank of the 22,519 € CBS-AXA SRL 20 October, 2015 – 20 May, 2016 Development Nistru river Economic research and forecasts about the Business AO Centrul Analitic Independent 5 economic situation of the Transnistrian region 60,011 € Development 15 October, 2015 – 15 October, 2016 EXPERT-GRUP Creation of Job Opportunities through Business Business Chamber of Commerce and Industry of 6 Support for Youth in the Transnistria region 344,561 € Development 1 September, 2015 – 30 April, -

Progress Report for 2009

Contract number: 2009/219-955 Project Title: Building confidence between Chisinau and Tiraspol Report starting date: 01 January 2010 Report end date: 31 December 2011 Implementing agency: UNDP Moldova Country: Republic of Moldova Support to Confidence Building Measures II – Final Report 2010-2011 – submitted by UNDP Moldova 1 Table of Contents I. SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................................................. 3 II. CONTEXT ................................................................................................................................................................. 4 III. PROJECT BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................................. 5 1. BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT ............................................................................................................................................ 5 2. COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT ........................................................................................................................................ 6 3. CIVIL SOCIETY DEVELOPMENT ...................................................................................................................................... 7 4. SUPPORT TO CREATION OF DNIESTER EUROREGION AND RESTORATION OF RAILWAY TRAFFIC. ........................................... 7 IV. SUMMARY OF IMPLEMENTATION PROGRESS ......................................................................................... -

Advancing Democracy and Human Rights PROMO-LEX ASSOCIATION

advancing democracy and human rights THE CIVIC COALITION FOR FREE AND FAIR ELECTIONS PROMO-LEX ASSOCIATION REPORT #3 Monitoring the preterm parliamentary elections of 28 November 2010 Monitoring period: 26 October 2010 – 8 November 2010 Published on 11 November 2010 Promo-LEX is grateful for the financial and technical assistance offered by the United States of America Embassy in Chisinau, the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), and the National Democratic Institute for International Affairs (NDI). The opinions expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect those of the donors. Page 1 of 28 Third monitoring report on the preterm parliamentary elections of 28 November 2010 CONTENTS: I. SUMMARY II. PROMO-LEX MONITORING EFFORT III. INTRODUCTION A. Legal framework B. Electoral competitors C. Election authorities D. Local authorities E. Electoral campaigning F. Financial analysis G. Mass media H. National and international observers I. Transnistrian region IV. CONCERNS V. RECOMMENDATIONS Page 2 of 28 I. SUMMARY This report, covering the period from October 25 through November 8, 2010, describes the electoral environment and reviews from a legal perspective the recent developments in the election campaign, and the performance of the electoral competitors and of the local and election authorities. The election campaign is becoming increasingly intense, with cases of intimidation and abuse being registered both against electoral competitors and voters. While engaged in various campaigning activities, some candidates resort to the misuse of administrative resources and offering of “electoral gifts”. Promo-LEX salutes the impartiality of the election authorities in performing their duties. The Central Election Commission registered until the end of the authorization period 40 electoral competitors and issued warnings to the contenders that violated the rules. -

Proposal for Moldova

AFB/PPRC.24/29 26 February, 2019 Adaptation Fund Board Project and Programme Review Committee Twenty-Third Meeting Bonn, Germany, 12-13 March , 2019 Agenda Item 9 v) PROPOSAL FOR MOLDOVA AFB/PPRC.24/29 Background 1. The Operational Policies and Guidelines (OPG) for Parties to Access Resources from the Adaptation Fund (the Fund), adopted by the Adaptation Fund Board (the Board), state in paragraph 45 that regular adaptation project and programme proposals, i.e. those that request funding exceeding US$ 1 million, would undergo either a one-step, or a two-step approval process. In case of the one-step process, the proponent would directly submit a fully-developed project proposal. In the two-step process, the proponent would first submit a brief project concept, which would be reviewed by the Project and Programme Review Committee (PPRC) and would have to receive the endorsement of the Board. In the second step, the fully- developed project/programme document would be reviewed by the PPRC, and would ultimately require the Board’s approval. 2. The Templates approved by the Board (Annex 5 of the OPG, as amended in March 2016) do not include a separate template for project and programme concepts but provide that these are to be submitted using the project and programme proposal template. The section on Adaptation Fund Project Review Criteria states: For regular projects using the two-step approval process, only the first four criteria will be applied when reviewing the 1st step for regular project concept. In addition, the information provided in the 1st step approval process with respect to the review criteria for the regular project concept could be less detailed than the information in the request for approval template submitted at the 2nd step approval process. -

Report of the Observance of Human Rights and Freedoms in The

REPORT ON THE OBSERVANCE OF HUMAN RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS IN THE REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA IN 2016 CHISINAU, 2017 1 CONTENTS Foreword..................................................................................................................3 Universal Periodic Review..............................................................................................7 CHAPTER I OBSERVANCE OF HUMAN RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS IN THE REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA Equality before law and public authorities .............................................................................9 Legal status of foreign citizens and stateless persons …………………………………...…14 Right to a fair trial .................................................................................................................17 Right to life, physical and mental integrity…........................................................................22 Individual freedom and personal security.................................................................. 29 Private and family life…………...............................................................................31 Freedom of expression……………………………………………………………………..34 Right to information………………………………………………………………………..41 Right to health protection….……..........................................................................................44 Right to a clean environment…………..……………………………………………….......51 Right to vote and right to be elected .....................................................................................60 Freedom of assembly……………………………………………………………………….63 -

Request for Project/Programme Funding from the Adaptation Fund

REQUEST FOR PROJECT/PROGRAMME FUNDING FROM THE ADAPTATION FUND The annexed form should be completed and transmitted to the Adaptation Fund Board Secretariat by email or fax. Please type in the responses using the template provided. The instructions attached to the form provide guidance to filling out the template. Please note that a project/programme must be fully prepared (i.e., fully appraised for feasibility) when the request is submitted. The final project/programme document resulting from the appraisal process should be attached to this request for funding. Complete documentation should be sent to: The Adaptation Fund Board Secretariat 1818 H Street NW MSN P4-400 Washington, D.C., 20433 U.S.A Fax: +1 (202) 522-3240/5 Email: [email protected] Table of Contents Abbreviations and Acronyms ................................................................................................. vi PART I PROJECT INFORMATION ................................................................................. 1 Background and Context. ...................................................................................................... 1 A Geography ................................................................................................................................... 1 B Climate ......................................................................................................................................... 2 C Economy ..................................................................................................................................... -

Geological and Hydrological Survey for the Tintareni Landfill. Summary Moldova: Chisinau Solid Waste Project Feasibility Study C

Geological and Hydrological Survey for the Tintareni Landfill. Summary Moldova: Chisinau Solid Waste Project Feasibility Study Contract No. C32112/SWM2-2015-08-09 European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) Summary Report November 2016 This project is supported by the Government of Sweden. FICHTNER MANAGEMENT CONSULTING AG Stuttgart Berlin Sarweystrasse 5 D-70191 Stuttgart Tel.: +49 711 8995-750 Fax: +49 711 8995-1491 www.fmc.fichtner.de Contact person Dr. Maria Belova Chisinau landfill geological study results (Tintareni) Moldova: Chisinau Solid Waste Project Feasibility Study For public use Disclaimer The content of this report is intended for the exclusive use of FICHTNER's client and other agreed recipients. It may only be made available in whole or in part to third parties on non- reliance basis. FICHTNER is not liable to third parties for the completeness and accuracy of the information provided therein. 3 Chisinau landfill geological study results (Tintareni) Moldova: Chisinau Solid Waste Project Feasibility Study For public use Table of Contents Disclaimer 3 Table of Contents 4 List of Figures 5 List of Tables 5 List of Abbreviations 5 1. General Overview 6 2. Physical-geographical conditions 7 3. Geomorphology and geology of the investigated area 8 4. Results evaluation of the drilling works 8 5. Hydrologic characteristics 9 6. Geological-engineering characteristics of the investigation site 11 7. Slope and dam stability 12 4 Chisinau landfill geological study results (Tintareni) Moldova: Chisinau Solid Waste Project Feasibility Study For public use List of Figures Figure 1: Location of boreholes (BH) ......................................................................................... 6 Figure 2: 3D representation of intersecting lithologies.............................................................. -

The Projects Are Implemented in Cooperation with the Ecocatalyst Foundation NARRATIVE REPORT Reporting Organisation: National En

The projects are implemented in cooperation with the EcoCatalyst Foundation NARRATIVE REPORT Reporting Organisation: National Environmental Center Country: Republic of Moldova Reporting period: 2015 1 1. Background This project has the following major activities which were carried out in 2015: CNM – leader in IWRM in Moldova Developing a youth network “Love your river!” Festival of Bic river Collaboration with the Ministry of Internal Affairs to counteract cases of environmental pollution Various activities were organised in 2015 to strengthen the youth network “Love your river!”. In autumn 2015 it is envisaged to organise the first Forum of the Youth Network “Love your river!” in order to agree and plan the activities for 2016. The third edition of the Festival of Bic river “Love your river!” will be organised in 2016 due to the fact, that there were organised local elections in summer 2015 and the chairs of the District Councils were changed, now CNM will establish relations with the newly appointed Chairs of the District Councils and other newly elected representatives of public authorities to further implement the Bic river Rehabilitation Initiative and plan the organisation of the 3rd edition of the Bic Festival. Letters to ask for the support will be again sent to private companies and to the Mayoralty of Chisinau municipality who will be the host of the event. It is envisaged to involve more seriously those companies which will be included in the SCR program of CNM. CNM will continue to promote the creation and support the operation of the River Basin Councils. At the moment CNM is Technical Secretariat of the Bic Basin Council which is meeting 3-4 times a year to discuss solutions for the improvement of the environmental state of the river, and it has also helped the local authorities to create Ichel Basin Council (spring 2015), Tigheci Basin Council (autumn 2014, the second meeting was organised in winter 2015) and Larga Basin Council (autumn 2014, the second meeting was organised in winter 2015). -

Monitoring Report of the Webpages of the Courts of Law in the Republic of Moldova

rt Monitoring Report of the Webpages of the Courts of Law in the Republic of Moldova 1 CONTENTS 1. Supreme Court of Justice ……………………………………………………………………….... 4 2. Chisinau Court of Appeals…...………………………………………………………………….... 7 3. Balti Court of Appeals ….………………………………………………………………………... 9 4. Bender Court of Appeals …..…………………………………………………………………..... 12 5. Cahul Court of Appeals …..……………………………………………………………………... 13 6. Comrat Court of Appeals …..…………………………………………………………………… 15 7. Botanica District Court of Chisinau Municipality ….…………………………………………... 17 8. Buiucani District Court of Chisinau Municipality ….…………………………………………... 19 9. Centru District Court of Chisinau Municipality ….…………………………………………….. 20 10. Ciocana District Court of Chisinau Municipality ….…………………………………………… 21 11. Riscani District Court of Chisinau Municipality ….……………………………………………. 23 12. Balti District Court ….…………………………………………………………………………... 24 13. Bender District Court ….………………………………………………………………………... 25 14. Anenii Noi District Court ….……………………………………………………………………. 26 15. Basarabeasca District Court ….…………………………………………………………………. 27 16. Briceni District Court ….………………………………………………………………………... 28 17. Cahul District Court ….…………………………………………………………………………. 29 18. Cantemir District Court ….……………………………………………………………………… 30 19. Calarasi District Court ….……………………………………………………………………….. 32 20. Causeni District Court ….……………………………………………………………………….. 33 21. Ceadir Lunga District Court ….…...…………………………………………………………….. 34 22. Cimislia District Court ….………………………………………………………………………. 35 23. Comrat District Court -

Moldovan Institute for Human Rights

Resource Center for Human Rights (CReDO, www.CReDO.md), Moldovan Institute for Human Rights (MIHR, www.IDOM.md), National Roma Center (www.roma.md) Alternative Report on Implementation of UN CAT by Moldova Resource Center for Human Rights (CReDO) Moldovan Institute for Human Rights (IDOM) Roma National Center (CNR) FINAL DRAFT ALTERNATIVE REPORT TO THE 2nd Report of the Republic of Moldova on the Stage of Implementation of the UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION AGAINST TORTURE (UN CAT) 1 Resource Center for Human Rights (CReDO, www.CReDO.md), Moldovan Institute for Human Rights (MIHR, www.IDOM.md), National Roma Center (www.roma.md) Alternative Report on Implementation of UN CAT by Moldova About organizations Resource Center for Human Rights (CReDO), www.CReDO.md: - List of issues on the most stringent problems related to civil and political rights, for Human Rights Committee (in cooperation with Moldovan Institute for Human Rights and National Roma Center); - Report on the Implementation of the ICCPR (civil and political rights) for 2003-2009 by Modova, submitted to UN Human Rights Committee, 97th session, October 2009 (in cooperation with Moldovan Institute for Human Rights and National Roma Center); - Security, Liberty and Torture in the Aftermath of April 2009 events (in cooperation with Moldovan Institute for Human Rights); - Policy paper on the creation of national preventive mechanism against torture to implement the provisions of the Optional Protocol (OP CAT) to UN Convention against Torture ratified by Moldova in March 2006 (includes -

Best Practice in Local Government

BBEESSTT PPRRAACCTTIICCEE IINN LLOOCCAALL GGOOVVEERRNNMMEENNTT Prepared By the Council of Europe Centre of Expertise for Local Government Reform in cooperation with CoE experts John Jackson, Cezary Trutkowski and Irfhan Mururajani April 2015, Council of Europe, Strasbourg Table of contents PART 1: IDENTIFYING AND CELEBRATING BEST PRACTICE .................................................... 1 1. THE BACKGROUND TO BEST PRACTICE ................................................................... 1 2. THE MEANING OF BEST PRACTICE ............................................................................. 6 3. HOW TO ORGANISE BEST PRACTICE PROGRAMMES ........................................... 12 4. KEY STAGES IN A BEST PRACTICE PROGRAMME................................................. 15 PART 2: TRANSFORMING BEST PRACTICE INTO A TRAINING PROGRAMME ................... 25 3. EVENTS AND ACTIVITIES ............................................................................................ 28 a) Best Practice Open Day .................................................................................................. 28 b) Workshops ...................................................................................................................... 33 c) Learning exchanges ........................................................................................................ 33 d) Study visits ..................................................................................................................... 33 4. PUBLICATIONS .............................................................................................................. -

REPUBLIC of MOLDOVA Handbook on Transparency and Citizen Participation

REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA Handbook on Transparency and Citizen Participation Council of Europe Original: Handbook on Transparency and Citizen Participation in the Republic of Moldova (English version) The opinions expressed in this work are the responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Council of Europe. The reproduction of extracts (up to 500 words) is authorised, except for commercial purposes as long as the integrity of the text is preserved, the excerpt is not used out of context, does not provide incomplete information or does not otherwise mislead the reader as to the nature, scope or content of the text. The source text must always be acknowledged as follows other requests concerning the reproduction/translation of all or part of the document, should be addressed to the Directorate of Communications, Council of Europe (F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex or [email protected]). All other requests concerning this publication should be addressed to the Congress of Local and Regional Authorities of the Council of Europe. Congress of Local and Regional Authorities of the Council of Europe Cover design and layout: RGOLI F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex France © Council of Europe, February 2021 E-mail: [email protected] (2nd edition) Acknowledgements This Handbook on Transparency and Citizen Participation in the Republic of Moldova was (2015-2017) in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, the Republic of Moldova, Ukraine, and Belarus. This project was implemented as part of the Partnership for Good Governance 2015-2017 between the Council of Europe and the European Union. This updated edition was Reinforcing the culture of dialogue and consultation of local authorities in the Republic of Moldova 2020-2021), implemented within the framework of the Council of Europe Action Plan for the Republic of Moldova 2017- 2020.