Bashiri SP.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Farvardin Yasht Contents Fravashi Is Generally Translated As the “Guardian Spirit/Angel.” It Occurs for a Total of 539 Times in the Extant Avesta

Weekly Zoroastrian Scripture Extract # 136 – Who were all these Stalwarts of our Religion? - Corroboration from Aafrin-e-Rapithwan with Farvardin Yasht for a few of them! Hello all Tele Class friends: Afargaan, Farokshi, Satums, Baaj – Prayers for our dear departed ones I grew up in Tarapur in a Panthaki’s family and on each anniversary occasions of dear departed ones of family or of our Tarapur Humdins, usually referred to as the day of Baaj, the following four prayers were performed in the name of the departed: Afargaan, Farokshi, 3 Satums and a Baaj. During the Muktaad days, these prayers were performed for all the departed ones whose Behraa (vessels) were placed on the Muktaad tables. In current scenario in India, especially during the Muktaad days, very few Atash Behrams/Agiaries perform all these prayers for all dear departed ones. In North America, except for the major cities, only Afargaan and may be Satums are performed for the dear departed ones. In these prayers, Farokshi is nothing but the Farvardin Yasht with Satum No Kardo in front of it. In this WZSE, we will cover some very interesting facts about some contents of the Farvardin Yasht. Farvardin Yasht Contents Fravashi is generally translated as the “Guardian Spirit/Angel.” It occurs for a total of 539 times in the extant Avesta. Of these, 353 times (65.5%) are in the Farvardin Yasht. This Yasht (Veneration) is devoted to Fravashi. It is the longest Yasht in the extant Avesta with 157 verses. The Meher Yasht, in honor of Mithra, the deity of light and Pasture land, is the second with 145 verses, and the Aban Yasht, in honor of Aredvi Sura Anahita, the River Deity is the third with 132 verses. -

On the Good Faith

On the Good Faith Zoroastrianism is ascribed to the teachings of the legendary prophet Zarathustra and originated in ancient times. It was developed within the area populated by the Iranian peoples, and following the Arab conquest, it formed into a diaspora. In modern Russia it has evolved since the end of the Soviet era. It has become an attractive object of cultural produc- tion due to its association with Oriental philosophies and religions and its rearticulation since the modern era in Europe. The lasting appeal of Zoroastrianism evidenced by centuries of book pub- lishing in Russia was enlivened in the 1990s. A new, religious, and even occult dimension was introduced with the appearance of neo-Zoroastrian groups with their own publications and online websites (dedicated to Zoroastrianism). This study focuses on the intersectional relationships and topical analysis of different Zoroastrian themes in modern Russia. On the Good Faith A Fourfold Discursive Construction of Zoroastrianism in Contemporary Russia Anna Tessmann Anna Tessmann Södertörns högskola SE-141 89 Huddinge [email protected] www.sh.se/publications On the Good Faith A Fourfold Discursive Construction of Zoroastrianism in Contemporary Russia Anna Tessmann Södertörns högskola 2012 Södertörns högskola SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications Cover Image: Anna Tessmann Cover Design: Jonathan Robson Layout: Jonathan Robson & Per Lindblom Printed by E-print, Stockholm 2012 Södertörn Doctoral Dissertations 68 ISSN 1652-7399 ISBN 978-91-86069-50-6 Avhandlingar utgivna vid -

ABMBNIA (Varmio) B. H. KENNETT. ARMENIA

HI ABMBNIA (Varmio) •with any such supposition. It ia a safe inference indistinguishable. la timea of need c? danger from 1 S 67fl;, 2 S (33rr- that the recognized method man requires a god that ia near, and nofc a god of carrying the Ark in early times was in a sacred that is far off. It ia bjy BO means a primitive con- cart (i.e, a cart that had been used for no other ception which we find an the dedicatory prayer put purpose) drawn by COTVS or bulls.* The use of into the mouth of Solomon (1K 84*1*), that, if people horned cattle might possibly denote that the Ark go out to battle against their enemy, and they was in some way connected with lunar worship; prayto their God towards the house which is built in any case, Jiowever, they probably imply that to His name, He will make their prayer and the god contained in the Ark was regarded aa the supplication hoard to the heaven in which He god of fertility (see Frazer, Adonis, Attu, Osiris, really dwells,* Primitive warriors wanted to have pp. 46,80),f At first sight it is difficult to suppose their goda in their midst. Of what use was the that a aerpent could ever be regarded aa a god of Divine Father (see Nu 2129) at home, when his sona fertility, but "whatever the origin of serpent-worship were in danger in the field ? It waa but natural, may be—and we need not assume that it has been therefore, that the goda should be carried out everywhere identical — there can be little doubt wherever their help waa needed (2S 5ai; cf. -

ZOROASTRIANISM Chapter Outline and Unit Summaries I. Introduction

CHAPTER TEN: ZOROASTRIANISM Chapter Outline and Unit Summaries I. Introduction A. Zoroastrianism: One of the World’s Oldest Living Religions B. Possesses Only 250,000 Adherents, Most Living in India C. Zoroastrianism Important because of Influence of Zoroastrianism on Christianity, Islam, Middle Eastern History, and Western Philosophy II. Pre-Zoroastrian Persian Religion A. The Gathas: Hymns of Early Zoroastrianism Provide Clues to Pre- Zoroastrian Persian Religion 1. The Gathas Considered the words of Zoroaster, and are Foundation for all Later Zoroastrian Scriptures 2. The Gathas Disparage Earlier Persian Religions B. The Aryans (Noble Ones): Nomadic Inhabitants of Ancient Persia 1. The Gathas Indicate Aryans Nature Worshippers Venerating Series of Deities (also mentioned in Hindu Vedic literature) a. The Daevas: Gods of Sun, Moon, Earth, Fire, Water b. Higher Gods, Intar the God of War, Asha the God of Truth and Justice, Uruwana a Sky God c. Most Popular God: Mithra, Giver and Benefactor of Cattle, God of Light, Loyalty, Obedience d. Mithra Survives in Zoroastrianism as Judge on Judgment Day 2. Aryans Worship a Supreme High God: Ahura Mazda (The Wise Lord) 3. Aryan Prophets / Reformers: Saoshyants 97 III. The Life of Zoroaster A. Scant Sources of Information about Zoroaster 1. The Gathas Provide Some Clues 2. Greek and Roman Writers (Plato, Pliny, Plutarch) Comment B. Zoroaster (born between 1400 and 1000 B.C.E.) 1. Original Name (Zarathustra Spitama) Indicates Birth into Warrior Clan Connected to Royal Family of Ancient Persia 2. Zoroaster Becomes Priest in His Religion; the Only Founder of a World Religion to be Trained as a Priest 3. -

NEWSLETTER CENTER for IRANIAN STUDIES NEWSLETTER Vol

CIS NEWSLETTER CENTER FOR IRANIAN STUDIES NEWSLETTER Vol. 13, No.2 MEALAC–Columbia University–New York Fall 2001 Encyclopædia Iranica: Volume X Published Fascicle 1, Volume XI in Press With the publication of fascicle ISLAMIC PERSIA: HISTORY AND 6 in the Summer of 2001, Volume BIOGRAPHY X of the Encyclopædia Iranica was Eight entries treat Persian his- completed. The first fascicle of Vol- tory from medieval to modern ume XI is in press and will be pub- times, including “Golden Horde,” lished in December 2001. The first name given to the Mongol Khanate fascicle of volume XI features over 60 ruled by the descendents of Juji, the articles on various aspects of Persian eldest son of Genghis Khan, by P. Jack- culture and history. son. “Golshan-e Morad,” a history of the PRE-ISLAMIC PERSIA Zand Dynasty, authored by Mirza Mohammad Abu’l-Hasan Ghaffari, by J. Shirin Neshat Nine entries feature Persia’s Pre-Is- Perry. “Golestan Treaty,” agreement lamic history and religions: “Gnosti- arranged under British auspices to end at Iranian-American Forum cism” in pre-Islamic Iranian world, by the Russo-Persian War of 1804-13, by K. Rudolph. “Gobryas,” the most widely On the 22nd of September, the E. Daniel. “Joseph Arthur de known form of the old Persian name Encyclopædia Iranica’s Iranian-Ameri- Gobineau,” French man of letters, art- Gaub(a)ruva, by R. Schmitt. “Giyan ist, polemist, Orientalist, and diplomat can Forum (IAF) organized it’s inau- Tepe,” large archeological mound lo- who served as Ambassador of France in gural event: a cocktail party and pre- cated in Lorestan province, by E. -

To:$M.R$Ahmad$Shahid$ Special$Rapporteur$On$The

To:$M.r$Ahmad$Shahid$ Special$Rapporteur$on$the$human$rights$situation$in$Iran$ $ Dear%Sir,% % such%as%equal%rights%to%education%for%everyone,%preventing%the%dismissal%and%forced%retirements%of% dissident%university%professors,%right%of%research%without%limitations%in%universities%and%to%sum%up% expansion%of%academic%liberties.%Student%activists%have%also%been%pursuing%basic%rights%of%the%people% such%as%freedom%of%speech,%press,%and%rallies,%free%formation%and%function%of%parties,%syndicates,%civil% associations%and%also%regard%of%democratic%principles%in%the%political%structure%for%many%years.% % But%unfortunately%the%regime%has%rarely%been%friendly%towards%students.%They%have%always%tried%to%force% from%education,%banishments%to%universities%in%remote%cities,%arrests,%prosecutions%and%heavy%sentences% of%lashing,%prison%and%even%incarceration%in%banishment,%all%for%peaceful%and%lawful%pursuit%of%the% previously%mentioned%demands.%Demands%which%according%to%the%human%rights%charter%are%considered% the%most%basic%rights%of%every%human%being%and%Islamic%Republic%of%Iran%as%a%subscriber%is%bound%to% uphold.% % The%government%also%attempts%to%shut%down%any%student%associations%which%are%active%in%peaceful%and% lawful%criticism,%and%their%members%are%subjected%to%all%sorts%of%pressures%and%restrictions%to%stop%them.% Islamic%Associations%for%example%which%have%over%60%years%of%history%almost%twice%as%of%the%Islamic% republic%regimeE%and%in%recent%years%have%been%the%only%official%criticizing%student%associations%in% universities,%despite%their%massive%number%of%student%members,%have%been%shut%down%by%the% -

The Zarathushtrian Daena in a Nutshell

THE ZARATHUSHTRIAN DAENA IN A NUTSHELL TO BE 'GOOD' REQUIRES SPIRITUAL ENERGY GENERATED BY 'TARIKAT'S Who is a Parsi? Whenever this question is asked, a heap of legal, social and highly argumentative babbles are thrown in the answer. Poor Justice Davar is brought in, 'the big change in times' is put forward and a number of why's and why not's are shot out, with hollow vehemence, like "if men, why not women?" (The question is too worn out by repetition to need any elaboration.) All this endless discussions are hopelessly tangential and off the mark to the main issue, which is: a Parsi is basically a person of Religion - the Zarathushtrian Daena. Her or his life is required to be totally founded on the Daena. For a Parsi, Life and Religion are not only equal but congruent. Each point of the one should coincide with each point of the other. Every breath should inhale and exhale Daena and he or she must be aware and conscious of this. Three Good's and Freedom of Choice What is the Daena? Ask any common Parsi; the answer by nine out of ten will be: Manashni, Gavashni, Kunashni - Good thoughts, words and deeds. But if you ask: "What is your definition of Good?", he will stare at you as if you have gone mad. "You don’t know what is good?" "No", you can pursue the argument, "the definition varies with every person; what is thought as good by one is stamped as 'horribly bad' by the other. Hitler thought, killing of jews was very good. -

In the Alphabetic Order Q Follows A, a Follows E, C Follows C, 1J Follows N, S Follows S, I Follows Z

INDEX [In the alphabetic order q follows a, a follows e, c follows c, 1J follows n, s follows s, i follows z. In arranging words no distinction has been made between long and short vowels. Pahlavi anrllater forms are generally given in square brackets after the Avestan ones, ancl are entered separately only when there is a significant difference between the two.l Aban see Apas 273· A ban Niyayes 52; 271-2. Airyaman 56-7; his part at Fraso.kar<Jti, Aban Yast 73· 57. 242, 291. abstract divinities 23-4; 58, 59; 203. Airyanam Vaejah [f:ranve)] 144-5; 274- Aditi 55· S· Adityas 55; 83. Airyama isyo 56; 261; 263; 265. Adurbad i Mahraspandan 35; 288. Aiwisriithra [Aiwisriithrim] the 4th watch Aesma demon of Wrath, 87; companion ( giih) of the 24-hour day, from sunset till of the daevas, 201; flees at the last day midnight, 124; under the guardianship of before the Saosyant, 283; the Arabs are the fravasis, 124, 259. of his seed, 288. Aka Manah 283. aethrapati [erbad, herbad] 12. Akhtya 161. Afrasiyab see FralJrasyan *Ala demon of purpureal fever, 87 n. 20. afrinagan an "outer" religious ceremony, Amahraspand see Amasa Spanta 168; legends connected with the offerings Amestris xog; 112. made at it, 281. amaratat ,..., Ved. amrtatva-, "long life" after-life pagan belief in it beneath the or "immortality" II5 n. 32. earth, xog-xo, II2, IIS; in Paradise, no- Amaratat [Amurdad] personification of 12; Zoroastrian beliefs, 235-42, 328. "Long Life" and "Immortality", one of the Agni identified with Apam Napat, 45-6; 7 great Amasa Spantas (q.v.), 203; dis the nature of his primary concept, 69-70. -

The History and Characteristics of Traditional Sports in Central Asia : Tajikistan

The History and Characteristics of Traditional Sports in Central Asia : Tajikistan 著者 Ubaidulloev Zubaidullo journal or The bulletin of Faculty of Health and Sport publication title Sciences volume 38 page range 43-58 year 2015-03 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2241/00126173 筑波大学体育系紀要 Bull. Facul. Health & Sci., Univ. of Tsukuba 38 43-58, 2015 43 The History and Characteristics of Traditional Sports in Central Asia: Tajikistan Zubaidullo UBAIDULLOEV * Abstract Tajik people have a rich and old traditions of sports. The traditional sports and games of Tajik people, which from ancient times survived till our modern times, are: archery, jogging, jumping, wrestling, horse race, chavgon (equestrian polo), buzkashi, chess, nard (backgammon), etc. The article begins with an introduction observing the Tajik people, their history, origin and hardships to keep their culture, due to several foreign invasions. The article consists of sections Running, Jumping, Lance Throwing, Archery, Wrestling, Buzkashi, Chavgon, Chess, Nard (Backgammon) and Conclusion. In each section, the author tries to analyze the origin, history and characteristics of each game refering to ancient and old Persian literature. Traditional sports of Tajik people contribute as the symbol and identity of Persian culture at one hand, and at another, as the combination and synthesis of the Persian and Central Asian cultures. Central Asia has a rich history of the traditional sports and games, and significantly contributed to the sports world as the birthplace of many modern sports and games, such as polo, wrestling, chess etc. Unfortunately, this theme has not been yet studied academically and internationally in modern times. Few sources and materials are available in Russian, English and Central Asian languages, including Tajiki. -

Newsletter Spring 2007 Final.Indd

CENTER FOR IRANIAN STUDIES NEWSLETTER Vol. 19, No. 1 SIPA-Columbia University-New York Spring 2007 ENCYCLOPÆDIA IRANICA GALA BENEFIT FASCICLE 1 OF VOLUME XIV PUBLISHED DINNER EW ORK ITY Fascicle 1 of Volume XIV features ISLAMIC History; v. LOCAL HISTORIOG- N Y C the remaining sections of the entry RAPHY; vi. MEDIEVAL PERIOD; vii. THE MAY 5, 2007 ISFAHAN, a series of 22 articles that SAFAVID PERIOD; VIII. THE QAJAR began in Fascicle 6 of Volume XIII. PERIOD; ix. THE PAHLAVI PERIOD The city of Isfahan has served as one AND POST-REVOLUTION ERA; x. of the most important urban centers MONUMENTS; xi. ISFAHAN SCHOOL on the Iranian plateau since ancient OF PAINTING AND CALLIGRAPHY; xii. times and has gained, over centuries BAZAAR, PLAN AND FUNCTION; xiii. of urbanization, many significant monu- CRAFTS; xiv. MODERN ECONOMY AND IN- ments. Isfahan is home to a number of DUSTRIES; xv. EDUCATION AND CULTURAL monuments that have been designated AFFAIRS; xvi. ISFAHAN IN THE MIRROR OF by UNESCO as World Heritage Sites. It FOLKLORE AND LEGEND; xvii. ARMENIAN is Persiaʼs third largest city, after Tehran COMMUNITY (referred to JULFA); xviii. and Mashad, with a population of over JEWISH COMMUNITY; xix. JEWISH DIA- 1.4 million in 2004. LECTS; xx. GEOGRAPHY OF THE MEDIAN The series explores the following DIALECTS; xxi. PROVINCIAL DIALECTS; Dr. Maryam Safai topics: i. GEOGRAPHY; ii. HISTORICAL XXII. GAZI DIALECT. GEOGRAPHY; iii. POPULATION; iv. PRE- Continued on page 2 The Gala Benefit Dinner for the Encyclopædia Iranica will be held in the Rotunda of Columbia University MAJOR DONORS TO THE on May 5, 2007 from 6:30 PM to 1:30 AM. -

Summer/June 2014

AMORDAD – SHEHREVER- MEHER 1383 AY (SHENSHAI) FEZANA JOURNAL FEZANA TABESTAN 1383 AY 3752 Z VOL. 28, No 2 SUMMER/JUNE 2014 ● SUMMER/JUNE 2014 Tir–Amordad–ShehreverJOUR 1383 AY (Fasli) • Behman–Spendarmad 1383 AY Fravardin 1384 (Shenshai) •N Spendarmad 1383 AY Fravardin–ArdibeheshtAL 1384 AY (Kadimi) Zoroastrians of Central Asia PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Copyright ©2014 Federation of Zoroastrian Associations of North America • • With 'Best Compfiments from rrhe Incorporated fJTustees of the Zoroastrian Charity :Funds of :J{ongl(pnffi Canton & Macao • • PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 28 No 2 June / Summer 2014, Tabestan 1383 AY 3752 Z 92 Zoroastrianism and 90 The Death of Iranian Religions in Yazdegerd III at Merv Ancient Armenia 15 Was Central Asia the Ancient Home of 74 Letters from Sogdian the Aryan Nation & Zoroastrians at the Zoroastrian Religion ? Eastern Crosssroads 02 Editorials 42 Some Reflections on Furniture Of Sogdians And Zoroastrianism in Sogdiana Other Central Asians In 11 FEZANA AGM 2014 - Seattle and Bactria China 13 Zoroastrians of Central 49 Understanding Central 78 Kazakhstan Interfaith Asia Genesis of This Issue Asian Zoroastrianism Activities: Zoroastrian Through Sogdian Art Forms 22 Evidence from Archeology Participation and Art 55 Iranian Themes in the 80 Balkh: The Holy Land Afrasyab Paintings in the 31 Parthian Zoroastrians at Hall of Ambassadors 87 Is There A Zoroastrian Nisa Revival In Present Day 61 The Zoroastrain Bone Tajikistan? 34 "Zoroastrian Traces" In Boxes of Chorasmia and Two Ancient Sites In Sogdiana 98 Treasures of the Silk Road Bactria And Sogdiana: Takhti Sangin And Sarazm 66 Zoroastrian Funerary 102 Personal Profile Beliefs And Practices As Shown On The Tomb 104 Books and Arts Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor, editor(@)fezana.org AMORDAD SHEHREVER MEHER 1383 AY (SHENSHAI) FEZANA JOURNAL FEZANA Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar TABESTAN 1383 AY 3752 Z VOL. -

Narguess Farzad SOAS Membership – the Largest Concentration of Middle East Expertise in Any Institution in Europe

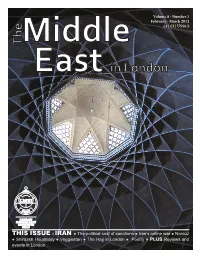

Volume 8 - Number 3 February - March 2012 £4 | €5 | US$6.5 THIS ISSUE : IRAN ● The political cost of sanctions ● Iran’s online war ● Norouz ● Shirazeh Houshiary ● Veggiestan ● The Hajj in London ● Poetry ● PLUS Reviews and events in London Volume 8 - Number 3 February - March 2012 £4 | €5 | US$6.5 THIS ISSUE : IRAN ● The political cost of sanctions ● Iran’s online war ● Norouz ● Shirazeh Houshiary ● Veggiestan ● The Hajj in London ● Poetry ● PLUS Reviews and events in London Interior of the dome of the house at Dawlat Abad Garden, Home of Yazd Governor in 1750 © Dr Justin Watkins About the London Middle East Institute (LMEI) Volume 8 - Number 3 February – March 2012 Th e London Middle East Institute (LMEI) draws upon the resources of London and SOAS to provide teaching, training, research, publication, consultancy, outreach and other services related to the Middle Editorial Board East. It serves as a neutral forum for Middle East studies broadly defi ned and helps to create links between Nadje Al-Ali individuals and institutions with academic, commercial, diplomatic, media or other specialisations. SOAS With its own professional staff of Middle East experts, the LMEI is further strengthened by its academic Narguess Farzad SOAS membership – the largest concentration of Middle East expertise in any institution in Europe. Th e LMEI also Nevsal Hughes has access to the SOAS Library, which houses over 150,000 volumes dealing with all aspects of the Middle Association of European Journalists East. LMEI’s Advisory Council is the driving force behind the Institute’s fundraising programme, for which Najm Jarrah it takes primary responsibility.