The Battle for Schools in Ghazni – Or, Schools As a Battlefield

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Education in Danger

Education in Danger Monthly News Brief September Attacks on education 2019 The section aligns with the definition of attacks on education used by the Global Coalition to Protect Education under Attack (GCPEA) in Education under Attack 2018. Africa This monthly digest comprises Kenya threats and incidents of Around 12 September 2019: In Mathemba, Wote town, Makueni violence as well as protests county, several students were reportedly beaten and injured by police and other events affecting officer who stormed the Mathemba Secondary School during a planned education. strike. Sources: Standard Media and Batatv It is prepared by Insecurity Somalia Insight from information 26 September 2019: In Mogadishu, an IED reportedly planted by al available in open sources. Shabaab detonated, striking a bulletproof vehicle carrying Turkish engineers of the education body Maarif Foundation near the KM-5 intersection. Source: AA Access data from the Education in Danger Monthly News Brief South Africa on HDX Insecurity Insight. 02 September 2019: In Port Elizabeth, Eastern Cape province, violent clashes ensued between student protestors and security officials at Nelson Mandela University. The students were demonstrating against Visit our website to download previous Education in Danger the lack of action taken by the university in response to concerns about Monthly News Briefs. safety on campus. Following the violence, seven students were reportedly arrested. Sources: News 24, Herald Live I and Herald Live II Join our mailing list to receive monthly reports on insecurity South Sudan affecting provision of education. 05 September 2019: In Yei River state, government and opposition forces continued to occupy schools, despite orders from their senior commanders to vacate the buildings. -

23 September 2010

SIOC – Afghanistan: UNITED NATIONS CONFIDENTIAL UN Department of Safety and Security, Afghanistan Security Situation Report, Week 38, 17- 23 September 2010 JOINT SECURITY ANALYSIS The number of security incidents experienced a dramatic increase over the previous week. This increase included primarily armed clashes, IED incidents and stand-off attacks, and was witnessed in all regions. At a close look, the massive increase is due to an unprecedented peak of security incidents recorded on Election Day 18 September, with incidents falling back to the September average of 65 per day afterwards. Incidents were more widely spread than compared to last year’s Election Day on 20 August 2009, but remained within the year-on-year growth span predicted by UNDSS-A. As last year, no spectacular attacks were recorded on 18 September, as the insurgents primarily targeted the population in order to achieve a low voter turn-out. Kunduz recorded the highest numbers in the NER on Election Day, while Baghlan has emerged as the AGE centre of focus afterwards. In the NR, Faryab accounted for the majority of incidents, followed by Balkh; Badghis recorded the bulk of the security incidents in the WR. The south to east belt accounted for the majority of the overall incidents, with a slight change to the regional dynamics with the SER recording nearly double the number of incidents as the SR, followed by the ER. Kandahar and Uruzgan accounted for the majority of incidents in the SR, while lack of visibility and under-reporting from Hilmand Province continues to result in many of the incidents in the SR remaining unaccounted for. -

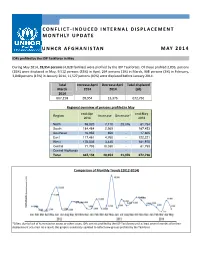

C Ict-I D C D I T R a Di P Ac M T M T Pdat Cr a a I Ta Ma 2014

CONFLICT - INDUCED INTERNAL DIS PLACEMENT MONTHLY UPDATE UNHCR AFGHANISTAN MAY 2014 IDPs profiled by the IDP Taskforce in May During May 2014, 28,954 persons (4,828 families) were profiled by the IDP Taskforces. Of those profiled 2,895, persons (10%) were displaced in May, 9,512 persons (33%) in April, 264 persons (1%) in March, 908 persons (3%) in February, 3,848 persons (13%) in January 2014, 11,527 persons (40%) were displaced before January 2014. Total Increase April Decrease April Total disp laced March 2014 2014 (all) 2014 667,158 28,954 23,376 672,736 Regional overview of persons profiled in May end-Apr end-May Region Increase Decrease* 2014 2014 North 98,020 7,110 23,376 81,754 South 184,484 2,969 187,453 Southeast 16,955 650 - 17,605 East 117,461 4,760 - 122,221 West 178,535 3,435 - 181,970 Central 71,703 10,030 - 81,733 Central Highlands - - - Total 667,158 28,954 23,376 672,736 Comparison of Monthly Trends (2012-2014) *Often, due to lack of humanitarian access or other issues, IDPs are not profiled by the IDP Taskforces until at least several months after their displacement occurred. As a result, this graph is constantly updated to reflect new groups profiled by the Taskforce Map of IDPs profiled in May 2014 by place of displacement IDPs Profiled in April *Provinces marked in red experienced displacement greater than 500 persons; those marked in orange less than 500 persons Snapshot of IDPs Profiled in May 2014 by Province Central Region - 10,030 IDPs profiled during May 2014 Maidan Wardak 836 families (6,154 individuals) were displaced from different districts of Maidan Wardak to the provincial centre of the same province during the reporting period. -

People to Help Improve Ghazni Security

افغانستان آزاد – آزاد افغانستان AA-AA چو کشور نباشـد تن من مبـــــــاد بدین بوم وبر زنده یک تن مــــباد همه سر به سر تن به کشتن دهیم از آن به که کشور به دشمن دهیم www.afgazad.com [email protected] زبان های اروپائی European Languages http://www.pajhwok.com/en/2017/01/08/people-help-improve-ghazni-security-amarkhel People to help improve Ghazni Security 1/8/2017 The police chief Sunday said people had promised him cooperation with security forces in improving security situation of southern Ghazni province. Brig. Gen. Aminullah Amarkhel in an exclusive interview with Pajhwok Afghan News said militants would not be able to destabilize Ghazni. He recently visited Giro, Zanakhan, Andar and some other districts and met local residents. Amarkhel said Taliban militants had tasted defeat in many areas of Ghazni. “If the central government provides me two helicopters, I will make Ghazni a hell for Daesh and Taliban,” he said. He said Daesh or Islamic State (IS) fighters had recently emerged in Giro district of Ghazni and Khak-i-Afghan district of neighbouring Zabul province, an issue he said needed attention of government leaders. “I will take harsh action against those who run kangaroo courts in Ghazni,” Amarkhel said. A provincial council member, Abdul Jamay Jamay, told Pajhwok security situation could improve if police were provided needed equipment. He said people were already cooperating with security forces. www.afgazad.com 1 [email protected] Lala Mohamamd, a resident of Ghazni city, said the government alone could not ensure security. He said people should fully support the government in ensuring security. -

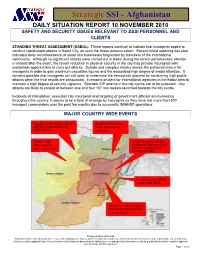

Daily Situation Report 10 November 2010 Safety and Security Issues Relevant to Sssi Personnel and Clients

Strategic SSI - Afghanistan DAILY SITUATION REPORT 10 NOVEMBER 2010 SAFETY AND SECURITY ISSUES RELEVANT TO SSSI PERSONNEL AND CLIENTS STANDING THREAT ASSESSMENT (KABUL): Threat reports continue to indicate that insurgents aspire to conduct coordinated attacks in Kabul City, as such the threat remains extant. Recent threat reporting has also indicated likely reconnaissance of areas and businesses frequented by members of the international community. Although no significant attacks were carried out in Kabul during the recent parliamentary election, or indeed after the event, the recent reduction in physical security in the city may provide insurgents with exploitable opportunities to carry out attacks. Suicide and complex attacks remain the preferred choice for insurgents in order to gain maximum casualties figures and the associated high degree of media attention. It remains possible that insurgents will still seek to undermine the democratic process by conducting high profile attacks when the final results are announced. It remains prudent for international agencies in the Kabul area to maintain a high degree of security vigilance. Sporadic IDF attacks in the city centre are to be expected. Any attacks are likely to consist of between one and four 107 mm rockets launched towards the city centre. Incidents of intimidation, executions by insurgents and targeting of government officials are increasing throughout the country. It seems to be a form of revenge by insurgents as they have lost more than 300 insurgent commanders over the past -

Translation of the Death List As Given by Late Afghan Minister of State Security Ghulam Faruq Yaqoubi to Lord Bethell in 1989

Translation of the death list as given by late Afghan Minister of State Security Ghulam Faruq Yaqoubi to Lord Bethell in 1989. The list concerns prisonners of 1357 and 1358 (1978-1979). For further details we refer to the copy of the original list as published on the website. Additional (handwritten) remarks in Dari on the list have not all been translated. Though the list was translated with greatest accuracy, translation errors might exist. No.Ch Name Fathers Name Profession Place Accused Of 1 Gholam Mohammad Abdul Ghafur 2nd Luitenant Of Police Karabagh Neg. Propaganda 2 Shirullah Sultan Mohammad Student Engineering Nerkh-Maidan Enemy Of Rev. 3 Sayed Mohammad Isa Sayed Mohammad Anwar Mullah Baghlan Khomeini 4 Sefatullah Abdul Halim Student Islam Wardak Ikhwani 5 Shujaudin Burhanudin Pupil 11th Grade Panjsher Shola 6 Mohammad Akbar Mohabat Khan Luitenant-Colonel Kohestan Ikhwani 7 Rahmatullah Qurban Shah Police Captain Khanabad Ikhwani 8 Mohammad Azam Mohammad Akram Head Of Archive Dpt Justice Nejrab Ikhwani 9 Assadullah Faludin Unemployed From Iran Khomeini 10 Sayed Ali Reza Sayed Ali Asghar Head Of Income Dpt Of Trade Chardehi Khomeini 11 Jamaludin Amanudin Landowner Badakhshan Ikhwani 12 Khan Wasir Kalan Wasir Civil Servant Teachers Education Panjsher Khomeini 13 Gholam Reza Qurban Ali Head Of Allhjar Transport. Jamal-Mina Khomeini 14 Sayed Allah Mohammad Ajan Civil Servant Carthographical Off. Sorubi Anti-Revolution 15 Abdul Karim Haji Qurban Merchant Farjab Ikhwani 16 Mohammad Qassem Nt.1 Mohammad Salem Teacher Logar Antirevol. -

Afghanistan HUMAN Lessons in Terror RIGHTS Attacks on Education in Afghanistan WATCH July 2006 Volume 18, Number 6 (C)

Afghanistan HUMAN Lessons in Terror RIGHTS Attacks on Education in Afghanistan WATCH July 2006 Volume 18, Number 6 (C) Lessons in Terror Attacks on Education in Afghanistan Glossary...........................................................................................................................................1 I. Summary......................................................................................................................................3 Plight of the Education System...............................................................................................6 Sources and Impact of Insecurity............................................................................................8 International and Afghan Response to Insecurity................................................................9 Key Recommendations...........................................................................................................10 II. Background: Afghanistan Since the Fall of the Taliban ...................................................13 The Taliban’s Ouster, the Bonn Process, and the Afghanistan Compact ......................13 Insecurity in Afghanistan........................................................................................................17 Education in Afghanistan and its Importance for Development ....................................23 III. Attacks on Schools, Teachers, and Students ....................................................................31 Who and Why ..........................................................................................................................32 -

Civilian Casualties During 2007

UNITED NATIONS UNITED NATIONS ASSISTANCE MISSION IN AFGHANISTAN UNAMA CIVILIAN CASUALTIES DURING 2007 Introduction: The figures contained in this document are the result of reports received and investigations carried out by UNAMA, principally the Human Rights Unit, during 2007 and pursuant to OHCHR’s monitoring mandate. Although UNAMA’s invstigations pursue reliability through the use of generally accepted procedures carried out with fairness and impartiality, the full accuracy of the data and the reliability of the secondary sources consulted cannot be fully guaranteed. In certain cases, and due to security constraints, a full verification of the facts is still pending. Definition of terms: For the purpose of this report the following terms are used: “Pro-Governmental forces ” includes ISAF, OEF, ANSF (including the Afghan National Army, the Afghan National Police and the National Security Directorate) and the official close protection details of officials of the IRoA. “Anti government elements ” includes Taliban forces and other anti-government elements. “Other causes ” includes killings due to unverified perpetrators, unexploded ordnances and other accounts related to the conflict (including border clashes). “Civilian”: A civilian is any person who is not an active member of the military, the police, or a belligerent group. Members of the NSD or ANP are not considered as civilians. Grand total of civilian casualties for the overall period: The grand total of civilian casualties is 1523 of which: • 700 by Anti government elements. • -

Ghazni District: Giro

UNHCR Field Office Ghazni DISTRICT PROFILE DATE: 11/09/2002 PROVINCE GHAZNI Geo-Code: 6 DISTRICT GIRO Geo-Code: 612 Population in 1990: Settled: 19,284 CURRENT ESTIMATED POPULATION Sources: 40, 260 individuals (8,052 families with an average 5 District and villages Representatives and members per family). WHO statistics for SO Ghazni (42,485, updated in 2001). ETHNIC COMPOSITION Pashtun 100% Hazara % Tajik % Uzbek % Turkmen % Balouch % Other ( ) % CURRENT ESTIMATED IDP POPULATION 645 individuals (129 families with an average 5 Sources: members per family). District and villages Representatives. CURRENT ESTIMATED RETURNEE POPULATION (ACCORDING TO UNHCR RECORDS) Returned Returned IDPs Updated Update Children Under Refugees Female Household2 (Ind./Fam.) 2002 on on 121 (Ind./Fam.) 2002 09/ 2002 32 individuals 09/09/02 (6 families) AUTHORITY Head of the District: Abdul Nabee ( Hezb Mahaz-e-Milli) Security Commander (Gul Ahmed- Harakat e Inqilab Islami), Assistant to District Administrator (Mawlawee Nouruldin), Department of Properties, Department of Education and Department of Agriculture. Functioning Authorities: There is no Court based in the district; however, once a week, a judge from neighbouring Andar district comes to Pana, capital of the district, and deals with pending cases. GENERAL SITUATION Giro is located at the South East of Ghazni province; approximately a two and a half-hour drive from Ghazni city. The district is a wide plain, with scattered low mountains. The district shares borders with Andar to the North, Qarabagh to the West and Ab Band to the southwest. Paktika province is located at its East. On a general basis, the district is regarded as a Southern district along with Ab Band, Nawa, Moqur and Gelan where NGOs and agencies are – due to security concerns- reluctant to operate. -

Afghanistan Anti-Government Elements (Ages)

European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan Anti-Government Elements (AGEs) Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan Anti-Government Elements (AGEs) Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). PDF ISBN: 978-92-9485-648-7 doi: 10.2847/14756 BZ0220563ENN © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2020 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyright statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © ResoluteSupportMedia/Major James Crawford, Kandahar, Afghanistan 11 April 2011 url CC BY 2.0 Taliban fighters met with Government of the Republic of Afghanistan officials in Kandahar City, 11 April 2011, and peacefully surrendered their arms as part of the government's peace and reintegration process. 4 — AFGHANISTAN: ANTI-GOVERNMENT ELEMENTS - EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT Acknowledgements This report was drafted by the European Asylum Support Office Country of Origin Information (COI) Sector. The following national asylum and migration departments and organisations contributed by reviewing this report: Denmark, Danish Immigration Service The Netherlands, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis, Ministry of Justice ACCORD, the Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments and organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, but it does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. -

Health and Integrated Protection Needs in Ghazni Province

[Compa ny name] Assessment Report- Health and Integrated Protection Needs in Ghazni Province Abdul Qadir Baqakhil Dr. Waseel Rahimi Akbar Ahmadi Vijay Raghavan Final Report Acknowledgements The study team thank representatives of the following institutions who have met us in both Kabul and Ghazni during the assessment. WHO – Kabul, UNICEF – Ghazni, Emergency – Ghazni, DACAAR – Kabul, Provincial Health Directorate, Ghazni; Provincial Hospital, Ghazni; Afghanistan Red Crescent Society (ARCS), Ghazni; DoRR, Ghazni; ICRC – Kabul and Ghazni, Swedish Committee for Afghanistan, Ghazni; AADA BPHS and EPHS team in Ghazni Thanks of INSO for conducting the assessment of the field locations and also for field movements Special thanks to the communities and their representatives who have travelled all the way from their villages in distant districts and participated in the consultation workshop we had in Ghazni. Our sincere thanks to the District wise focal points, health facility staff and all support staff of AADA, Ghazni who tirelessly supported in the field assessment and arrangement of necessary logistics for the assessment team. Our special thanks to Dr. Samim Nifkhar, Provincial Manager, BPHS and EPHS, AADA in Ghazni for his kind support and providing all the needed information and coordinating the field mission and stakeholders’ consultations in the province. Without his support the mission wouldn’t be possible. We thank the founder/Director of AADA, Dr Jamaluddin Jawid who proposed for this joint programme planning between Johanniter and AADA beyond our existing programme of Community Midwifery Education in Takhar province and expand the partnership to Ghazni, the neediest province for health and that too for trauma care. -

ICOIC Accepts Constitution Has Some Problems

Quote of the Day In the truest sense, freedom cannot be bestowed; Email: [email protected] it must be achieved. Phone: 0093 (798) 341861/ 799-157371 Franklin D. Roosevelt www.thedailyafghanistan.com Reg: No 352 Volume No. 3484 Monday January 09, 2017 Jaddi 20, 1395 www.outlookafghanistan.net Price: 15/-Afs 200,000 IDPs and ICOIC Accepts Constitution Return Refugees Has Some Problems Urgently Need Aid KABUL - The Independent controversy about the func- Commission Overseeing the tion of parliament and elec- Implementation of the Con- tions, whether parliament stitution (ICOIC) on Sunday can still continue its job said there are problems with without holding elections,” the constitution and some ar- said Abdul Wahid Ferozaie, ticles need to be clarified. a lawyer. ICOIC earlier said there were Lawyers also said the consti- KABUL - Up to 200,000 re- million returned from Paki- challenges in terms of im- tution needs to be amended turn refugees and internally stan and Iran. plementing 20 articles of the and some articles should be displaced persons (IDPs) are The officials said many re- constitution and as a result revised.“Articles related to in urgent need of humanitar- turn refugees have still not these had not been fully im- courts, to interpretation of ian assistance, officials of the been resettled in their origi- plemented. the constitution, to renewing Afghanistan National Disas- nal regions. “Article seven of the consti- elections and holding elec- ter Management Authority With the surge in violence tution says that Afghanistan tions, need to be amended,” (ANDMA) and Ministry of in the country over the past will implement those con- said Ainuddin Bahaduri, ex- Refugees and Repatriations year, thousands of Afghans ventions that it has joined.