Locking Private Sector Participation Into Infrastructure Development in the Philippines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PPP Road Projects

PPP Road Projects ROGELIO L. SINGSON Secretary Department of Public Works and Highways November 18, 2010 1 PRESENTATION OUTLINE Strategic Directions Expressways in Operation and Under Construction Projects for Bidding in 2011 PPP Pipeline of Projects under the Medium Term Other DPWH PPP Projects Under Development 2 STRATEGIC DIRECTIONS Upgrading the national road network in terms of quality and safety standards with focus on urban centers and strategic tourism destinations; Completion of critical bridges along national roads; Develop more Public-Private Partnership (PPP) projects for much needed infrastructure and level playing field for investments; Address private sector concerns – Transparency, RROW, regulatory risks and government support; Pursue contracts for long term maintenance period (5-10 years) in road and bridge construction; and Introduce innovative technology such as bio-engineering for road slope protection 3 EXPRESSWAYS IN OPERATION Project Name Subic-Clark-Tarlac Expressway (93.77 km) North Luzon Tollway (82.62 km) C-5 Expressway (Segment 8.1, 2.34 km) Metro Manila Skyway, Stage 1 (13.43 km At-grade & 9.30 km Viaduct) Manila-Cavite Toll Expressway (6.75 km) South Luzon Tollway (36.03 km) Southern Tagalog Arterial Road (41.90 km) 4 Total Length = 286.14 km EXPRESSWAY UNDER CONSTRUCTION/PLANNING Project Name Tarlac- Pangasinan- La Union Toll Expressway (TPLEX) (88.58 km) North Luzon Tollway, C-5 Expressway Segment 8.2 - 10.23 km Segment 9 - 4.06 km Segment 10 - 5.63 km NLEx-SLEx Link Expressway (13.4 km) (Unsolicited proposal for NEDA review and subject to Swiss Challenge) Manila-Cavite Toll Expressway, R-1 Extension (7.00 km) Metro Manila Skyway, Stage 2 (6.88 km) Total Length = 135.78 km 5 EXISTING SITUATION IN METRO MANILA AND NEARBY AREAS Arterial road network composed of 6 circumferential and 10 radial roads proposed in the late 1960s. -

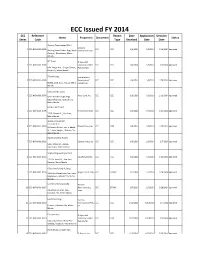

ECC Issued FY 2014 ECC Reference Report Date Application Decision Name Proponent Document Status Series Code Type Received Date Date

ECC Issued FY 2014 ECC Reference Report Date Application Decision Name Proponent Document Status Series Code Type Received Date Date Alabang Town Center BPO 1 Alabang 1 ECC-NCR-1401-0001 ECC IEEC 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 1/16/2014 Approved Alabang Town Center, Brgy. Ayala, Commercial Corp. Alabang,, Muntinlupa, Metro Manila IBP Tower Ortigas and 2 ECC-NCR-1401-0003 Company Limited ECC IEEC 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 2/6/2014 Approved Julia Vargas Ave., Ortigas Center,, Partnershipp Pasig City, Metro Manila T-Park Project Fort Bonifacio 3 ECC-NCR-1401-0005 Development ECC IEEC 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 1/28/2014 Approved B18,L4, 26th, BGC,, Taguig, Metro Corporation Manila Vertis North Towers 4 ECC-NCR-1401-0006 Ayala Land, Inc. ECC IEEC 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 1/16/2014 Approved Vertis North Triangle, Brgy. Bagong Pag-asa,, Quezon City, Metro Manila Fortune Hill Project 5 ECC-NCR-1401-0008 Filinvest Land, Inc. ECC IEEC 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 1/20/2014 Approved 173 P. Gomez St.,, San Juan, Metro Manila Studio A Residential Condominium 6 ECC-NCR-1401-0009 Filinvest Land, Inc. ECC IEER 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 1/20/2014 Approved 99 Xavierville Ave., cor. E. Abada St., Loyola Heights,, Quezon City, Metro Manila Plastic Recycling Project 7 ECC-NCR-1401-0011 Sanplas Industries ECC IEEC 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 2/7/2014 Approved 6390 Tatalon St., Ugong,, Valenzuela, Metro Manila Shipbuilding and Repair Yard 8 ECC-NCR-1401-0013 Sas Shipyard, Inc. -

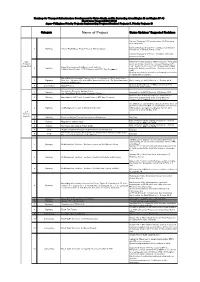

Name of Project Status Updates/ Suggested Revisions

Roadmap for Transport Infrustructure Development for Metro Manila and Its Surrunding Areas(Region III and Region IV-A) Short-term Program(2014-2016) Japan-Philippines Priority Projects: Implementing Progress(Comitted Projects 5, Priority Projects 8) Category Name of Project Status Updates/ Suggested Revisions Contract Packages I & II covering about 14.65 km have been completed. Contract Package III (2.22 km + 2 bridges): Construction 1 Highways Arterial Road Bypass Project Phase II, Plaridel Bypass Progress as of 25 April 2015 is 13.02%. Contract Package IV (7.74 km + 2 bridges): Still under procurement stage. ODA Notice to Proceed Issued to CMX Consortium. The project Projects is not specifically cited in the Transport Roadmap. LRT (Committed) Line 1 South Ext and Line 2 East Ext were cited instead, Capacity Enhancement of Mass Transit Systems 2 Railways separately. Updates on LRT Line 1 South Extension and in Metro Manila Project (LRT1 Extension and LRT 2 East Extentsion) O&M: Ongoing pre-operation activities; and ongoing procurement of independent consultant. Metro Manila Interchanges Construction VI - 2 packages d. EDSA/ North Ave. - 3 Highways West Ave.- Mindanao Ave. and EDSA/ Roosevelt Ave. and f. C5: Green Meadows/ Confirmed by the NEDA Board on 17 October 2014 Acropolis/CalleIndustria Ongoing. Detailed Design is 100% accomplished. Final 4 Expressways CLLEX Phase I design plans under review. North South Commuter Railway Project 1 Railways Approved by the NEDA Board on 16 February 2015 (ex- Mega Manila North-South Commuter Railway) New Item, Line 2 West Extension not included in the 2 Railways Metro Manila CBD Transit System Project (LRT2 West Extension) short-term program (until 2016). -

Japan International Cooperation Agency

JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS The Study of Masterplan on High Standard Highway Network Development In the Republic of the Philippines RegionalRegional GrowthGrowth PolePole CityCity Frontage Road (PrimaryPrimary CityCity) Grade Separation Small City (Tertiary City) Small City ( ) Tertiary City Small City ss (Tertiary City) pa Small City y (Tertiary City) RRegionalegional GGrowthrowth B PolePole CCityity Medium City Special (Secondary City) (PrimaryPrimary CCityity) Economic Zone National Road Town Small City MegaMega CityCity (Tertiary City) HSH 1 International Airport IInternationalnternational PPortort HSH 1 FINAL REPORT Project Profile JULY 2010 CTI ENGINEERING INTERNATIONAL CO., LTD. EID JR 10-100(4/4) JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS THE STUDY OF MASTER PLAN ON HIGH STANDARD HIGHWAY NETWORK DEVELOPMENT IN THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES FINAL REPORT PROJECT PROFILE JULY 2010 CTI ENGINEERING INTERNATIONAL CO., LTD. EXCHANGE RATE February 2010 1 PhP = 1.95 Japan Yen 1 US$ = 46.31 Philippine Peso 1 US$ = 90.14 Japan Yen Central Bank of the Philippines TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. PROPOSED HSH NETWORK • North of Metro Manila 1 • Metro Manila 2 • South of Metro Manila 3 2. PROPOSED IMPLEMENTATION PLAN • Present and Ongoing Projects 4 • Proposed Network in 2020 5 • Proposed Network in 2030 6 • Proposed Network Beyond 2030 7 3. PROJECT PROFILE Project Project Name No. 1 NLEX-SLEX Link -

Okura-At-Home-Map-And-Directions

Bringing together Japanese Omotenashi with Filipino Warmth Hotel Okura Manila is located within Resorts World Manila, the first integrated resort in the Philippines. Ideal for both business and leisure, the area is a few minutes away from the airport and is surrounded by international premium boutiques and a wide variety of restaurants. Embracing serene ambience with a modern touch, the hotel has state-of-the-art facilities, a rooftop pool with a bar, a relaxing wellness center, and up-to-date meeting rooms. Set to open this 2020, the luxury hotel epitomizes the essence of Japanese elegance and refinement enhanced by Filipino hospitality, making your stay harmonious and extraordinary. MANILA MARRIOTT RESORT DRIVE NEWPORT MALL AD TO MAKATI MARRIOTT GRAND BALLROOM CITY / NEWPORT BOULEVARD NEWPORT BOULEVARD BONIFACIO GLOBAL CITY SALES RO SHRINE OF HILTON ST. THERESE MANILA OF THE VE) CHILD JESUS PORTWOOD STREET (PALM DRI HOLIDAY INN HORIZON ’S EXPRESS CENTER LD (formerly AIR FORCE TOTAL NA SHERATON GAS STAR CRUISES GENERAL CENTRE) MANILA STATION MCDO HOSPITAL ANDREWS AVENUE / NAIA EXPRESSWAY NAIA TERMINAL 3 VILLAMOR AIR BASE WHERE TO FIND US Hotel Okura Manila is located at 2 Portwood Street, Resorts World Manila, Newport City, Pasay City 1309. NEWPORT BOULEVARD RESORT DRIVE HILTON MANILA PICK-UP POINT 2nd Floor Hotel Okura Manila PORTWOOD STREET PORTWOOD STREET IS ONE-WAY PICK-UP POINT: Ground Floor entryway Entrance to Resort Drive HORIZON CENTER SHERATON MANILA available only for vehicles (formerly STAR CRUISES CENTRE) coming from NAIAX/Skyway CURBSIDE PICK-UP Okura At Home menu items can be picked up at the Hotel Okura Manila Ground Floor driveway located at Portwood Street. -

BUS Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

BUS bus time schedule & line map BUS Malanday MIA via Pasay Rtda MOA Coastal Road View In Website Mode The BUS bus line (Malanday MIA via Pasay Rtda MOA Coastal Road) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Mercury Drug Store, Macarthur Highway, Malanday, Valenzuela City →Naia Rd, Parañaque City, Manila: 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM (2) Natalia, 9516 →Mercury Drug Store, Macarthur Highway, Malanday, Valenzuela City: 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest BUS bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next BUS bus arriving. Direction: Mercury Drug Store, Macarthur BUS bus Time Schedule Highway, Malanday, Valenzuela City →Naia Rd, Mercury Drug Store, Macarthur Highway, Malanday, Parañaque City, Manila Valenzuela City →Naia Rd, Parañaque City, Manila Route Timetable: 128 stops VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:00 AM - 10:00 PM Monday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Mercury Drug Store, Macarthur Highway, Malanday, Valenzuela City Tuesday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Marisyl School, Macarthur Highway, Malanday Wednesday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Valenzuela City Thursday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Macarthur Highway, Dalandanan, Valenzuela City Friday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Macarthur Highway / Santiago Road Interchange, Saturday 12:00 AM - 10:00 PM Dalandanan, Valenzuela City Iskinita, Philippines Ign Pharmacy, Macarthur Highway, Dalandanan, Valenzuela City BUS bus Info Direction: Mercury Drug Store, Macarthur Highway, Dalandanan, Fire Sub Station, Macarthur Malanday, Valenzuela City →Naia Rd, Parañaque City, Highway, Dalandanan, Valenzuela City -

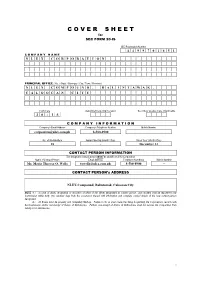

C O V E R S H E

C O V E R S H E E T for SEC FORM 20-IS SEC Registration Number A 1 9 9 7 0 1 4 5 1 C O M P A N Y N A M E N L E X C O R P O R A T I O N PRINCIPAL OFFICE ( No. / Street / Barangay / City / Town / Province ) N L E X C O M P O U N D , B A L I N T A W A K , C A L O O C A N C I T Y Form Type Department requiring the report Secondary License Type, If Applicable 2 0 - I S C O M P A N Y I N F O R M A T I O N Company’s Email Address Company’s Telephone Number Mobile Number [email protected] 8-580-8900 – No. of Stockholders Annual Meeting (Month / Day) Fiscal Year (Month / Day) 18 - December 31 CONTACT PERSON INFORMATION The designated contact person MUST be an Officer of the Corporation Name of Contact Person Email Address Telephone Number/s Mobile Number Ms. Maria Theresa O. Wells [email protected] 8-580-8900 – CONTACT PERSON’s ADDRESS NLEX Compound, Balintawak, Caloocan City NOTE 1 : In case of death, resignation or cessation of office of the officer designated as contact person, such incident shall be reported to the Commission within thirty (30) calendar days from the occurrence thereof with information and complete contact details of the new contact person designated. 2 : All Boxes must be properly and completely filled-up. -

DOTR Presentation FINAL

1 Philippine Infrastructure Development Agenda Secretary Arthur P. Tugade Department of Transportation 2 WE ARE AN ARCHIPELAGO 3 Image from https://www.kisspng.com/png-philippines-map-stock-photography-philippines-730866/ No. of Islands: 7,107 Major Islands: 3 (Luzon, Visayas, & Mindanao) 4 Image from https://www.kisspng.com/png-philippines-map-stock-photography-philippines-730866/ TOTAL POPULATION: over 100 Million MANILA POPULATION DENSITY: 42,857 persons/sq.km Photo from: http://investvine.com/philippines-population-reach-107-million-year/philippines-population/ 5 20 years behind in infrastructure 6 PHILIPPINE GOVERNMENT SPENDING ON INFRASTRUCTURE UNTIL 2022 7 8 Dept. of Public Works and Highways (DPWH): Strategic Infrastructure Programs and Policies 9 Philippine High Standard Highway Network Program 1,044.6 kilometers PHP518.0bn (USD10.1bn) Davao High Standard Highway Network 86.1 kilometers PHP65.3bn (USD1.3bn ) Luzon Spine Expressway Network 884.7 kilometers PHP424.7bn (USD8.3bn) Cebu High Standard Highway Network 73.8 kilometers 10 10 PHP28.0bn (USD544.1mn) Luzon Spine Expressway Network • From 382 km to 1,267 km High Standard Highways in Luzon. Travel time from Ilocos to Bicol will be reduced from 19 hours and 40 minutes to 8 hours and 15 minutes. • 884.7 kilometers • PHP424.7bn (USD8.3bn) Cavite-Laguna Expressway Plaridel By-Pass Road Central Luzon Link Expressway, Phase I 11 Agri-Infrastructure Support Program A total of PHP 24.80 bn (USD 481.55mn) was released from 2016 to 2018 for the construction / Improvement of 2,269.51 kilometers of Farm to Market Roads and Farm to Mill Roads. 2,269.51 kilometers PHP24.80 Billion (£368.35 GBP ) 12 12 Mindanao Road Development Network Program • Construction / improvement of 2,600.7 km road network in Agusan Del Norte-Bukidnon Bdry. -

Metro Manila Infrastructure Development

Republic of the Philippines Department of Public Works and Highways URBAN ROAD PROJECTS OFFICE Metro Manila Infrastructure Development CARLOS G. MUTUC Project Director URBANURBAN ROADROAD PROJECTSPROJECTS OFFICEOFFICE URPOURPO isis aa specialspecial projectproject officeoffice responsibleresponsible forfor thethe formulationformulation andand developmentdevelopment ofof allall projectsprojects inin urbanurban areas,areas, particularlyparticularly inin MetroMetro Manila,Manila, financedfinanced byby JBIC,JBIC, WBWB andand ADB.ADB. ItIt alsoalso implementsimplements highlyhighly complexcomplex projectsprojects financedfinanced byby GOP.GOP. URPOURPO’s’s mainmain tasktask isis toto ensureensure aa moremore effectiveeffective andand expedientexpedient implementationimplementation ofof projectsprojects gearedgeared towardstowards completioncompletion ofof thethe MetroMetro ManilaManila MajorMajor RoadRoad NetworkNetwork System.System. URBANURBAN ROADROAD PROJECTSPROJECTS OFFICEOFFICE I STRATEGYSTRATEGYI -- addressaddress criticalcritical bottlenecksbottlenecks andand alleviatealleviate traffictraffic congestioncongestion inin MetroMetro Manila.Manila. GOALSGOALS -- completecomplete thethe MMMM roadroad networknetwork systemsystem -- constructconstruct interchangesinterchanges atat majormajor intersectionsintersections -- constructconstruct secondarysecondary roadsroads toto complementcomplement thethe MMMM RoadRoad NetworkNetwork -- rehabilitaterehabilitate primary/secondaryprimary/secondary roadsroads -- establishestablish aa validvalid urbanurban -

Securities and Exchange Commission Sec Form 20-Is

4/8/2017 Information Statement CR01997-2017 SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION SEC FORM 20-IS INFORMATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 17.1(b) OF THE SECURITIES REGULATION CODE 1. Check the appropriate box: Preliminary Information Statement Definitive Information Statement 2. Name of Registrant as specified in its charter DMCI Holdings, Inc. 3. Province, country or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization Philippines 4. SEC Identification Number ASO95-002283 5. BIR Tax Identification Code 004-703-376 6. Address of principal office 3/F Dacon Bldg. 2281 Chino Roces Avenue, Makati City Postal Code 1231 7. Registrant's telephone number, including area code (632) 888 3000 8. Date, time and place of the meeting of security holders May 16, 2017 9:30AM Main Lounge, Manila Polo Club, McKinley Road, Forbes Park, Makati City 9. Approximate date on which the Information Statement is first to be sent or given to security holders Apr 24, 2017 10. In case of Proxy Solicitations: Name of Person Filing the Statement/Solicitor The Management of the Corporation Address and Telephone No. 3/F Dacon Bldg. 2281 Chino Roces Avenue, Makati City / (632) 888 3000 11. Securities registered pursuant to Sections 8 and 12 of the Code or Sections 4 and 8 of the RSA (information on number of shares and amount of debt is applicable only to corporate registrants): Title of Each Class Number of Shares of Common Stock Outstanding and Amount of Debt Outstanding http://edge.pse.com.ph/openDiscViewer.do?edge_no=3b56dbf7815c723a3318251c9257320d#sthash.NKqoh1JN.dpbs 1/2 4/8/2017 Information Statement Common 13,277,470,000 Preferred 3,780 13. -

1. Introduction

Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS NAIA EXPRESSWAY PROJECT Preliminary Information Memorandum June 2011 Transaction Advisors Techinical Advisor With Assistance From DPWH – NAIA Expressway Project: Preliminary Information Memorandum June 2011 Disclaimer This Preliminary Information Memorandum (PIM) has been prepared by the Development Bank of the Philippines (DBP) and the International Finance Corporation (IFC) on behalf of their client, the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH), in line with their mandate as Transaction Advisors to the DPWH in the development, structuring and tendering of the NAIA Expressway Project as a Solicited Transaction under the Philippine Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) Law (or RA 6957 as amended by RA 7718). This PIM does not purport to be all-inclusive or to contain all of the information that a prospective participant may consider material or desirable in making its decision to participate in the tender. No representation or warranty, express or implied, is made, or responsibility of any kind is or will be accepted by the DBP, IFC, the DPWH, or the Republic of the Philippines (ROP) or any of its agencies, with respect to the accuracy and completeness of this preliminary information. The DPWH or the DBP/IFC may amend or replace any of the information contained in this booklet at any time, without giving any prior notice or providing any reason. In furnishing this PIM, the DBP, IFC, the DPWH, or the ROP or any of its agencies undertakes no obligation to provide recipients with access to any additional information, or to update, or to correct any inaccuracies which may become apparent in this PIM or any other information made available in connection with the Project prior to the actual tender. -

Fifth Edition

Fifth Edition CONTENTS 2 LIST OF PPP PROJECTS 4 THE PPP IN PH 5 PROJECTS UNDER PROCUREMENT 13 INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES 24 PROJECTS WITH ON-GOING STUDIES 43 AWARDED PROJECTS 52 THE PPP CENTER 53 POLICY INITIATIVES 54 DOING BUSINESS IN PH 55 THE PDMF 56 DIRECTORY 57 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS PIPELINE AWARDED PROJECTS • Daang Hari - SLEX Link Road Project OF PUBLIC- • PPP for School Infrastructure Project (PSIP) Phase I • NAIA Expressway (Phase II) Project PRIVATE • PPP for School Infrastructure Project (PSIP) Phase II • Modernization of the Philippine Orthopedic Center PARTNERSHIP • Automatic Fare Collection System • Mactan-Cebu International Airport Passenger PROJECTS Terminal Building • LRT Line 1 Cavite Extension and O&M (as of December 05, 2014) PROJECTS UNDER PROCUREMENT Various projects can be financed and • Integrated Transport System - Southwest Terminal implemented via PPPs - from traditional • Bulacan Bulk Water Supply Project infrastructure projects such as toll roads, • Integrated Transport System - South Terminal airports, and transport systems; to • Laguna Lakeshore Expressway Dike Project non-traditional infrastructure such as • Operation & Maintenance of LRT Line 2 ICT systems and facilities, and social • New Centennial Water Source - Kaliwa Dam infrastructure like education and health. Project • Cavite-Laguna Expressway PROJECTS TO BE ROLLED-OUT FOR PROCUREMENT OF CONSULTANTS TO CONDUCT • Development, Operations and Maintenance of the New Bohol (Panglao) Airport PRE-INVESTMENT STUDIES • Development, Operations and Maintenance of