Funding Transport Infrastructure Development in the Philippines: a Roadmap Toward Land Value Capture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PPP Road Projects

PPP Road Projects ROGELIO L. SINGSON Secretary Department of Public Works and Highways November 18, 2010 1 PRESENTATION OUTLINE Strategic Directions Expressways in Operation and Under Construction Projects for Bidding in 2011 PPP Pipeline of Projects under the Medium Term Other DPWH PPP Projects Under Development 2 STRATEGIC DIRECTIONS Upgrading the national road network in terms of quality and safety standards with focus on urban centers and strategic tourism destinations; Completion of critical bridges along national roads; Develop more Public-Private Partnership (PPP) projects for much needed infrastructure and level playing field for investments; Address private sector concerns – Transparency, RROW, regulatory risks and government support; Pursue contracts for long term maintenance period (5-10 years) in road and bridge construction; and Introduce innovative technology such as bio-engineering for road slope protection 3 EXPRESSWAYS IN OPERATION Project Name Subic-Clark-Tarlac Expressway (93.77 km) North Luzon Tollway (82.62 km) C-5 Expressway (Segment 8.1, 2.34 km) Metro Manila Skyway, Stage 1 (13.43 km At-grade & 9.30 km Viaduct) Manila-Cavite Toll Expressway (6.75 km) South Luzon Tollway (36.03 km) Southern Tagalog Arterial Road (41.90 km) 4 Total Length = 286.14 km EXPRESSWAY UNDER CONSTRUCTION/PLANNING Project Name Tarlac- Pangasinan- La Union Toll Expressway (TPLEX) (88.58 km) North Luzon Tollway, C-5 Expressway Segment 8.2 - 10.23 km Segment 9 - 4.06 km Segment 10 - 5.63 km NLEx-SLEx Link Expressway (13.4 km) (Unsolicited proposal for NEDA review and subject to Swiss Challenge) Manila-Cavite Toll Expressway, R-1 Extension (7.00 km) Metro Manila Skyway, Stage 2 (6.88 km) Total Length = 135.78 km 5 EXISTING SITUATION IN METRO MANILA AND NEARBY AREAS Arterial road network composed of 6 circumferential and 10 radial roads proposed in the late 1960s. -

Resettlement Plan PHI: EDSA Greenways Project (Balintawak

Resettlement Plan February 2020 PHI: EDSA Greenways Project (Balintawak Station) Prepared by Department of Transportation for the Asian Development Bank. This resettlement plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (As of 30 January 2020; Central Bank of the Philippines) Philippine Peso (PhP) (51.010) = US $ 1.00 ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank AH Affected Household AO Administrative Order AP Affected Persons BIR Bureau of Internal Revenue BSP Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas CA Commonwealth Act CGT Capital Gains Tax CAP Corrective Action Plan COI Corridor of Impact DA Department of Agriculture DAO Department Administrative Order DAR Department of Agrarian Reform DAS Deed of Absolute Sale DBM Department of Budget and Management DDR Due Diligence Report DED Detailed Engineering Design DENR Department of Environment and Natural Resources DILG Department of Interior and Local Government DMS Detailed Measurement Survey DO Department Order DOD Deed of Donation DOTr Department of Transportation DPWH Department of -

Assessment of Impediments to Urban-Rural Connectivity in Cdi Cities

ASSESSMENT OF IMPEDIMENTS TO URBAN-RURAL CONNECTIVITY IN CDI CITIES Strengthening Urban Resilience for Growth with Equity (SURGE) Project CONTRACT NO. AID-492-H-15-00001 JANUARY 27, 2017 This report is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of the International City/County Management Association (ICMA) and do not necessarily reflect the view of USAID or the United States Agency for International Development USAID Strengthening Urban Resilience for Growth with Equity (SURGE) Project Page i Pre-Feasibility Study for the Upgrading of the Tagbilaran City Slaughterhouse ASSESSMENT OF IMPEDIMENTS TO URBAN-RURAL CONNECTIVITY IN CDI CITIES Strengthening Urban Resilience for Growth with Equity (SURGE) Project CONTRACT NO. AID-492-H-15-00001 Program Title: USAID/SURGE Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID/Philippines Contract Number: AID-492-H-15-00001 Contractor: International City/County Management Association (ICMA) Date of Publication: January 27, 2017 USAID Strengthening Urban Resilience for Growth with Equity (SURGE) Project Page ii Assessment of Impediments to Urban-Rural Connectivity in CDI Cities Contents I. Executive Summary 1 II. Introduction 7 II. Methodology 9 A. Research Methods 9 B. Diagnostic Tool to Assess Urban-Rural Connectivity 9 III. City Assessments and Recommendations 14 A. Batangas City 14 B. Puerto Princesa City 26 C. Iloilo City 40 D. Tagbilaran City 50 E. Cagayan de Oro City 66 F. Zamboanga City 79 Tables Table 1. Schedule of Assessments Conducted in CDI Cities 9 Table 2. Cargo Throughput at the Batangas Seaport, in metric tons (2015 data) 15 Table 3. -

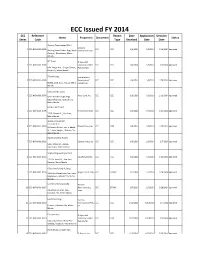

ECC Issued FY 2014 ECC Reference Report Date Application Decision Name Proponent Document Status Series Code Type Received Date Date

ECC Issued FY 2014 ECC Reference Report Date Application Decision Name Proponent Document Status Series Code Type Received Date Date Alabang Town Center BPO 1 Alabang 1 ECC-NCR-1401-0001 ECC IEEC 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 1/16/2014 Approved Alabang Town Center, Brgy. Ayala, Commercial Corp. Alabang,, Muntinlupa, Metro Manila IBP Tower Ortigas and 2 ECC-NCR-1401-0003 Company Limited ECC IEEC 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 2/6/2014 Approved Julia Vargas Ave., Ortigas Center,, Partnershipp Pasig City, Metro Manila T-Park Project Fort Bonifacio 3 ECC-NCR-1401-0005 Development ECC IEEC 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 1/28/2014 Approved B18,L4, 26th, BGC,, Taguig, Metro Corporation Manila Vertis North Towers 4 ECC-NCR-1401-0006 Ayala Land, Inc. ECC IEEC 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 1/16/2014 Approved Vertis North Triangle, Brgy. Bagong Pag-asa,, Quezon City, Metro Manila Fortune Hill Project 5 ECC-NCR-1401-0008 Filinvest Land, Inc. ECC IEEC 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 1/20/2014 Approved 173 P. Gomez St.,, San Juan, Metro Manila Studio A Residential Condominium 6 ECC-NCR-1401-0009 Filinvest Land, Inc. ECC IEER 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 1/20/2014 Approved 99 Xavierville Ave., cor. E. Abada St., Loyola Heights,, Quezon City, Metro Manila Plastic Recycling Project 7 ECC-NCR-1401-0011 Sanplas Industries ECC IEEC 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 2/7/2014 Approved 6390 Tatalon St., Ugong,, Valenzuela, Metro Manila Shipbuilding and Repair Yard 8 ECC-NCR-1401-0013 Sas Shipyard, Inc. -

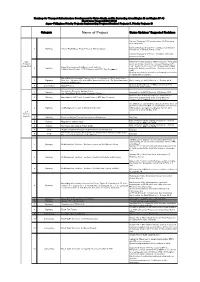

Name of Project Status Updates/ Suggested Revisions

Roadmap for Transport Infrustructure Development for Metro Manila and Its Surrunding Areas(Region III and Region IV-A) Short-term Program(2014-2016) Japan-Philippines Priority Projects: Implementing Progress(Comitted Projects 5, Priority Projects 8) Category Name of Project Status Updates/ Suggested Revisions Contract Packages I & II covering about 14.65 km have been completed. Contract Package III (2.22 km + 2 bridges): Construction 1 Highways Arterial Road Bypass Project Phase II, Plaridel Bypass Progress as of 25 April 2015 is 13.02%. Contract Package IV (7.74 km + 2 bridges): Still under procurement stage. ODA Notice to Proceed Issued to CMX Consortium. The project Projects is not specifically cited in the Transport Roadmap. LRT (Committed) Line 1 South Ext and Line 2 East Ext were cited instead, Capacity Enhancement of Mass Transit Systems 2 Railways separately. Updates on LRT Line 1 South Extension and in Metro Manila Project (LRT1 Extension and LRT 2 East Extentsion) O&M: Ongoing pre-operation activities; and ongoing procurement of independent consultant. Metro Manila Interchanges Construction VI - 2 packages d. EDSA/ North Ave. - 3 Highways West Ave.- Mindanao Ave. and EDSA/ Roosevelt Ave. and f. C5: Green Meadows/ Confirmed by the NEDA Board on 17 October 2014 Acropolis/CalleIndustria Ongoing. Detailed Design is 100% accomplished. Final 4 Expressways CLLEX Phase I design plans under review. North South Commuter Railway Project 1 Railways Approved by the NEDA Board on 16 February 2015 (ex- Mega Manila North-South Commuter Railway) New Item, Line 2 West Extension not included in the 2 Railways Metro Manila CBD Transit System Project (LRT2 West Extension) short-term program (until 2016). -

Chapter 5 Through Operation Policy

CHAPTER 5 THROUGH OPERATION POLICY 5.1 Through Operation Plan 5.1.1 Advantages of Through Operation Through operation will bring advantages to both railway users and railway enterprises. 1) The advantages for railway users are the alleviation of congestion at terminal stations; and the reduction of transport time by eliminating the necessity of changing trains. 2) The advantages for railway enterprises are the reduction of construction cost and rolling stock cost : and the enhancement of competitive power against other means of transport. 5.1.2 Draft of a Through Operations Plan We will study the possibility of through operations, including the track sections for which construction is already being planned, for the transportation authority responsible for railways for the Manila metropolitan area. A route map of these track sections is shown in Fig. 5.1.1. Of the track sections illustrated, we will study the following tracks, including LRT Line 1 and LRT Line3 that are already in operation, as well as planned tracks. No planning will be carried out for MRT Line 2 and LRT Line 4 because the through operations in the study results will be very complicated. (1) Plan proposal 1) Through operations on LRT Line 1 and LRT Line 3 ① Through operations at the Monumento Station in the north ② Through operations in the vicinity of the EDSA Station in the south Furthermore, LRT Line 6 now being planned is included in LRT Line 1. 2) Improvements and through operations for North Rail Line and MCX Line ① Through operations based on elevation of the track between Tayuman and Vitocruz (use existing track bed) 5 - 1 ② Through operations based on placing the track between Tayuman and Vitocruz underground (shorten by using a separate line) (2) Prerequisites for the comparative study 1) Date for start of through operations will be 2015. -

Technological Evolution of Manila Light Rail Transit System

International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology Vol.89 (2016), pp.9-16 http://dx.doi.org/10.14257/ijast.2016.89.02 Technological Evolution of Manila Light Rail Transit System Tomas U. Ganiron Jr IAENG, Hongkong College of Architecture, Qassim University, Buraidah City [email protected] Abstract This study focuses on the different elements of Manila Light Rail Transit System Line 1 in Metro Manila with the aim of characterizing its technological evolution and putting in context its impact in terms of what it is best designed for and what it can deliver. The study provides the concept of understanding the recent operation and developmental resolutions that the management of LRTA line 1 is providing as a preparation to uplift the socio-economic conditions of the commuters. Through the application of technology and scientific principles by means of transportation engineering for managing the facilities of the LRTA line 1 system, the system can provide safer, more rapid, more convenient, economic and environmental friendly way of transportation for the increasing demand of commuters. However, LRT 1 is best designed to substitute conventional railway services on routes where much higher capacity is required and to reduce travel time, further improving the railway service, also against other modes, therefore leading to mode substitution. Keywords: Highway engineering, railway transit, road engineering, transportation engineering 1. Introduction The traffic jams in Manila are staggering. Only a few traffic lights often disregarded separate the combatants. Every one force his way across the junctions, thus blocking everyone else and so the government decided to find a solution. -

Locking Private Sector Participation Into Infrastructure Development in the Philippines

Transport and Communications Bulletin for Asia and the Pacific No. 72, 2003 LOCKING PRIVATE SECTOR PARTICIPATION INTO INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT IN THE PHILIPPINES Noel Eli B. Kintanar, Ma. Lourdes S. Baclagon, Rodolfo T. Azanza, Jr. and Rina P. Alzate* ABSTRACT The Government of the Philippines continues to pursue its policy of encouraging the private sector to participate in the financing, construction, management and operation of infrastructure services and facilities in the country. Through the BOT Law, (Republic Act No. 7718), the Government has put together a portfolio of approximately US$ 25 billion in infrastructure projects involving private sector investments. A number of these are big- ticket transport projects which could not be funded solely from government coffers in view of the magnitude of the capital investments required. To ensure the steady promotion of infrastructure projects that are ready for private sector investments, the Government established the Build-Operate- Transfer Center (BOT Center), whose mandate is to find technical, legal, financial, economic and institutional solutions to help government implementing agencies to make BOT projects work. This paper focuses on the role of the BOT Center in promoting private sector projects and also discusses BOT as a contractual arrangement under the BOT Law and considerations that the private sector makes in undertaking a BOT project. INTRODUCTION It is a fact that infrastructure projects are capital-intensive propositions. In many countries, the difficulty of financing both the construction and the operation and maintenance of infrastructure services * BOT Center, Department of Trade and Industry, 6/F, EDPC Building, Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) Complex, Malate, Manila, fax: (632) 525-4416; e-mail: [email protected]. -

Japan International Cooperation Agency

JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS The Study of Masterplan on High Standard Highway Network Development In the Republic of the Philippines RegionalRegional GrowthGrowth PolePole CityCity Frontage Road (PrimaryPrimary CityCity) Grade Separation Small City (Tertiary City) Small City ( ) Tertiary City Small City ss (Tertiary City) pa Small City y (Tertiary City) RRegionalegional GGrowthrowth B PolePole CCityity Medium City Special (Secondary City) (PrimaryPrimary CCityity) Economic Zone National Road Town Small City MegaMega CityCity (Tertiary City) HSH 1 International Airport IInternationalnternational PPortort HSH 1 FINAL REPORT Project Profile JULY 2010 CTI ENGINEERING INTERNATIONAL CO., LTD. EID JR 10-100(4/4) JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS THE STUDY OF MASTER PLAN ON HIGH STANDARD HIGHWAY NETWORK DEVELOPMENT IN THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES FINAL REPORT PROJECT PROFILE JULY 2010 CTI ENGINEERING INTERNATIONAL CO., LTD. EXCHANGE RATE February 2010 1 PhP = 1.95 Japan Yen 1 US$ = 46.31 Philippine Peso 1 US$ = 90.14 Japan Yen Central Bank of the Philippines TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. PROPOSED HSH NETWORK • North of Metro Manila 1 • Metro Manila 2 • South of Metro Manila 3 2. PROPOSED IMPLEMENTATION PLAN • Present and Ongoing Projects 4 • Proposed Network in 2020 5 • Proposed Network in 2030 6 • Proposed Network Beyond 2030 7 3. PROJECT PROFILE Project Project Name No. 1 NLEX-SLEX Link -

Project Implementation Plan

CHAPTER 5 PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION PLAN The Supplementary Survey on North South Commuter Rail Project (Phase II-A) in the Republic of the Philippines FINAL REPORT CHAPTER 5 PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION PLANNING 5.1 Examination of Preliminary Construction Plan The construction of NSCR will require careful planning and organization, given the magnitude of the works, time constraints and the location of the works on busy national and arterial roads within Metropolitan Manila and Bulacan Province. 5.1.1 Temporary Works 1) Temporary Access to Site It is necessary to apply countermeasures flooding during heavy rain season because of the low ground level between Malolos and Caloocan. There is no problem with an access road to the site along the main road in this area. However, it is necessary to consider to construct temporary access to site far from main roads. In swampy areas between Malolos and San Fernando along the PNR Route, it is necessary to construct a temporary steel stage for machinery or materials transportation during construction. It is necessary to install sheet piles to avoid an intrusion of ground water during construction of the substructure. 2) Sufficient Space for the Works There are some narrow ROW sections between Malolos and Caloocan along the PNR Route. During construction of elevated structures, it is necessary to have more than 15m width for access road to secure access of many trucks, truck mixers and other construction equipment transportation to the site. After construction, the temporary access shall be maintained more than 15m width as a service road for maintenance or emergency evacuation. Source: JICA Study Team Figure 5.1.1 Necessary ROW for Elevated Structures 5-1 5.1.2 Viaduct 5.1.2.1 Foundations Viaduct foundations comprise of conventional bored piles and pile caps. -

Okura-At-Home-Map-And-Directions

Bringing together Japanese Omotenashi with Filipino Warmth Hotel Okura Manila is located within Resorts World Manila, the first integrated resort in the Philippines. Ideal for both business and leisure, the area is a few minutes away from the airport and is surrounded by international premium boutiques and a wide variety of restaurants. Embracing serene ambience with a modern touch, the hotel has state-of-the-art facilities, a rooftop pool with a bar, a relaxing wellness center, and up-to-date meeting rooms. Set to open this 2020, the luxury hotel epitomizes the essence of Japanese elegance and refinement enhanced by Filipino hospitality, making your stay harmonious and extraordinary. MANILA MARRIOTT RESORT DRIVE NEWPORT MALL AD TO MAKATI MARRIOTT GRAND BALLROOM CITY / NEWPORT BOULEVARD NEWPORT BOULEVARD BONIFACIO GLOBAL CITY SALES RO SHRINE OF HILTON ST. THERESE MANILA OF THE VE) CHILD JESUS PORTWOOD STREET (PALM DRI HOLIDAY INN HORIZON ’S EXPRESS CENTER LD (formerly AIR FORCE TOTAL NA SHERATON GAS STAR CRUISES GENERAL CENTRE) MANILA STATION MCDO HOSPITAL ANDREWS AVENUE / NAIA EXPRESSWAY NAIA TERMINAL 3 VILLAMOR AIR BASE WHERE TO FIND US Hotel Okura Manila is located at 2 Portwood Street, Resorts World Manila, Newport City, Pasay City 1309. NEWPORT BOULEVARD RESORT DRIVE HILTON MANILA PICK-UP POINT 2nd Floor Hotel Okura Manila PORTWOOD STREET PORTWOOD STREET IS ONE-WAY PICK-UP POINT: Ground Floor entryway Entrance to Resort Drive HORIZON CENTER SHERATON MANILA available only for vehicles (formerly STAR CRUISES CENTRE) coming from NAIAX/Skyway CURBSIDE PICK-UP Okura At Home menu items can be picked up at the Hotel Okura Manila Ground Floor driveway located at Portwood Street. -

BUS Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

BUS bus time schedule & line map BUS Malanday MIA via Pasay Rtda MOA Coastal Road View In Website Mode The BUS bus line (Malanday MIA via Pasay Rtda MOA Coastal Road) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Mercury Drug Store, Macarthur Highway, Malanday, Valenzuela City →Naia Rd, Parañaque City, Manila: 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM (2) Natalia, 9516 →Mercury Drug Store, Macarthur Highway, Malanday, Valenzuela City: 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest BUS bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next BUS bus arriving. Direction: Mercury Drug Store, Macarthur BUS bus Time Schedule Highway, Malanday, Valenzuela City →Naia Rd, Mercury Drug Store, Macarthur Highway, Malanday, Parañaque City, Manila Valenzuela City →Naia Rd, Parañaque City, Manila Route Timetable: 128 stops VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:00 AM - 10:00 PM Monday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Mercury Drug Store, Macarthur Highway, Malanday, Valenzuela City Tuesday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Marisyl School, Macarthur Highway, Malanday Wednesday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Valenzuela City Thursday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Macarthur Highway, Dalandanan, Valenzuela City Friday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Macarthur Highway / Santiago Road Interchange, Saturday 12:00 AM - 10:00 PM Dalandanan, Valenzuela City Iskinita, Philippines Ign Pharmacy, Macarthur Highway, Dalandanan, Valenzuela City BUS bus Info Direction: Mercury Drug Store, Macarthur Highway, Dalandanan, Fire Sub Station, Macarthur Malanday, Valenzuela City →Naia Rd, Parañaque City, Highway, Dalandanan, Valenzuela City