Issues in the New Millenium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Politicas Publicas Arranjos Pro

Universidade Estadual de Campinas Instituto de Economia Doutorado em Economia Aplicada Políticas Públicas e o Desenvolvimento de Arranjos Produtivos Locais em Regiões Periféricas Eduardo José Monteiro da Costa Orientador: Prof. Dr. Rinaldo Barcia Fonseca Tese apresentada ao Instituto de Economia da Universidade Estadual de Campinas para a obtenção do Título de Doutor em Economia Aplicada na área de concentração de Desenvolvimento Econômico. Campinas, 10 de agosto de 2007 i Ficha catalográfica elaborada pela biblioteca do Instituto de Economia/UNICAMP Costa, Eduardo Jose Monteiro da C823p Politicas publicas e o desenvolvimento de Arranjos Produtivos Locais em regiões perifericas / Eduardo Jose Monteiro da Costa. Campinas, SP: [s.n.], 2007. Orientador: Rinaldo Barcia da Fonseca. Tese (doutorado) – Universidade Estadua l de Campinas, Instituto de Economia. 1. Politicas publicas - Brasil. 2. Desenvolvimento regional - Brasil. 4. Clusters. I. Fonseca, Rinaldo Barcia da, 1949 - II. Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Instituto de Economia. III. Título. 08 -001 -BIE Título em Inglês: Public politics and the clusters development in periferic regions. Keywords : Clusters; Public politics – Brazil; Regional development – Brazil. Área de concentração : Desenvolvimento Econômico, Espaço e Meio Ambiente. Titulação : Doutorado em Economia Aplicada. Banca examinadora : Prof. Dr. Rinaldo Barcia da Fonseca. Prof. Dr. Carlos Américo Pacheco. Prof. Dr. Carlos Antonio Brandão. Prof. Dr. Cláudio Castelo Branco Puty. Prof. Dra. Edna Castro. Data da defesa: 10/08/2006. Programa de Pós-Graduação : Economia Aplicada. ii Universidade Estadual de Campinas Instituto de Economia Doutorado em Economia Aplicada Autor: Eduardo José Monteiro da Costa Título: Políticas Públicas e o Desenvolvimento de Arranjos Produtivos Locais em Regiões Periféricas Orientador: Prof. Dr. Rinaldo Barcia Fonseca Aprovada em: 10 de agosto de 2007 EXAMINADORES: Prof. -

Konzept Editorial Content AS24 Textkonzept Daniel Haefeli, 12.06.2006

Konzept Editorial Content AS24 Textkonzept Daniel Haefeli, 12.06.2006 Das Konzept Editorial Content AutoScout24 zeigt auf, wie der Editorial Content auf AutoScout24 und seiner Communities beschafft, kategorisiert, verarbeitet und publiziert werden kann. Das Konzept dient als Arbeitsanleitung für den Aufbau eines CMS und soll den mit der Umsetzung beauftragten WL-Ma- nager/GateKeeper alle relevanten Punkte im Bezug auf den Editorial Content der geplanten AS24- Community aufzeigen. Ziel des Konzepts zum Editorial Content ist, dass AS24 den qualitativ und quantitativ notwendigen redaktionellen Inhalt für den Betrieb der Plattform aufbauen und aktualisiert halten kann. Das Konzept ist in folgende Teile gegliedert: 0. Basisanalyse und strategische Ableitung 1. Redaktionskonzept 2. Marketing gegenüber Quellen 3. Contentverarbeitung und Publikation 4. Kalkulation Projekt-Start und -Betrieb Das Konzept ist primär auf die gestellten Anforderungen von AS24 zugeschnitten, besitzt aber das Potenzial, um in abgeänderter Form als Guideline für den Aufbau ähnlicher Strukturen in anderen Scout24-Bereichen die redaktionelle Betreuung zu organisieren. Die Kostenrechnung für den Editorial Content wird anhand einer Modellstruktur definiert. Die tatsäch- liche Kalkulation für die Umsetzung kann jedoch aufgrund ausstehender Verhandlungen mit Partnern, Abweichungen für Sprachübersetzungen und System der Verarbeitung/Publikation erst nach einer Konsolidierungsphase detailliert definiert werden. 0. Basisanalyse + Strategie für Editorial Content AS24 Die Grundlage für den Editorial Content AS24 wird in der Basisanalyse aufgezeigt. AS24 bewegt sich mit dem Schritt zum Aufbau von Communities weiter in Richtung eigenständiges Medium. Die Beson- derheit des Internet-Marktes ist die Kombination von Marktplatz und Werbeflächen-Verkauf. Die Funk- tion von AS24 wird von den Nutzern bezahlt (C- und B-Segmente). Dazu bietet AS24 verlegerische Dienstleistungen wie Publikation, Inserate-Verkauf und die zugehörige Administration. -

ARP-Chip Pumping Stations

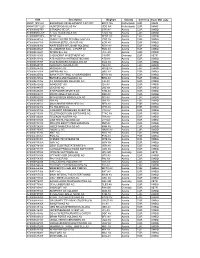

ARP-Chip Pumping Stations 1 Chip Pumping Station SP 250 Drives and Performance Throughput Up to 250 litres / min Pump Screw-type centrifugal pump 1,5 kW Fitting for pump 2“ Raker Drive Spur wheel back-geared motor 0,15 kW; 57 rpm Dimensions and Weights Overall external dimensions L x W x H 1096 x 1096 x 302 mm Inner tank Ø x H 1020 x 270 mm Maximum capacity of inner tank 200 l Feed height without cutting unit At least 300 mm - Feed opening length x width Variable up to a maximum of 500 x 500 mm Feed height with ZW 400 At least 702 mm + hopper (variable) Feed height with EZ 4 recessed At least 312 mm + Trichter (variable) Feed fl ange DN 100 No. of rakers 4 Net weight Approx. 300 Kg Other Information Cutting units on carriage ZW 300, ZW 400, EZ 4 Integrable cutting units ZW 300 Level measurement „Pump On-Off“ With ultrasonic sensor Level measurement „WHG-Overfull“ With fl uid level limit switch 2 Chip Pumping Station SP 500 Drives and Performance Throughput Up to 500 litres / min Pump Screw-type centrifugal pump 4,0 kW Fitting for pump 2“ Raker Drive Spur wheel back-geared motor 0,15 kW; 57 rpm Dimensions and Weights Overall external dimensions L x W x H 1436 x 1531 x 301 mm Inner tank Ø x H 1020 x 270 mm Maximum capacity of inner tank 350 l Feed height without cutting unit At least 300 mm - Feed opening length x width Variable up to a maximum of 500 x 500 mm Feed height with ZW 400 At least 702 mm + hopper (variable) Feed height with EZ 4 recessed At least 312 mm + Trichter (variable) Feed fl ange DN 100 No. -

Using Incidental Intellectual Property Rights to Block Parallel Imports

Scholarly Commons @ UNLV Boyd Law Scholarly Works Faculty Scholarship 2013 Wag the Dog: Using Incidental Intellectual Property Rights to Block Parallel Imports Mary LaFrance University of Nevada, Las Vegas -- William S. Boyd School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.law.unlv.edu/facpub Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons, and the International Trade Law Commons Recommended Citation LaFrance, Mary, "Wag the Dog: Using Incidental Intellectual Property Rights to Block Parallel Imports" (2013). Scholarly Works. 1184. https://scholars.law.unlv.edu/facpub/1184 This Article is brought to you by the Scholarly Commons @ UNLV Boyd Law, an institutional repository administered by the Wiener-Rogers Law Library at the William S. Boyd School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WAG THE DOG: USING INCIDENTAL INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS TO BLOCK PARALLEL IMPORTS Mary LaFrance* Cite as: Mary LaFrance, Wag the Dog: Using Incidental Intellectual Property Rights to Block ParallelImports, 20 MICH. TELECOMM. & TECH. L. REv. 45 (2013). This manuscript may be accessed online at repository.1aw.umich.edu. Federal law grants owners of intellectual property rights different de- grees of control over parallel imports depending on the nature of their exclusive rights. While trademarkowners enjoy strong control over un- authorized imports bearing their marks, theirprotection is less compre- hensive than that granted to owners of copyrights and patents. To broaden their rights, some trademark owners have incorporatedcopy- righted material into their products or packaging, enabling them to block otherwise lawful imports in contravention of the policies underly- ing trademark law. A 2013 Supreme Court decision has significantly narrowed the importation ban of copyright law, but there may be pres- sure to reinstate it. -

Subaru PDF-2016 WRX

2016 WRX/STI The best-handling, best-performing WRX and WRX STI ever. “The WRX is a 2015 AUTOMOBILE Magazine All-Star.” Automobilemag.com, November 2014 1 | 2016 WRX / STI Cornering Responsiveness Power Safety The WRX has all the hardware needed to corner Having excellent grip is only one half of the The powerful-yet-efficient 268-hp 2.0-liter The WRX backs up its potent performance with grace and speed. Starting with the suspension, handling equation. The other half is the driver’s direct-injection twin-scroll turbocharged features with appropriately robust safety measures. the WRX has an enviable setup—a rigid unibody sensation of control and precision, which the WRX SUBARU BOXER® engine propels the WRX With a standard Rear-Vision Camera, and available chassis with reinforced suspension mounting delivers with a quick 14.4:1 steering ratio, and the from 0-60 mph in a blistering 5.5 seconds.1 Blind-Spot Detection and Rear Cross-Traffic Alert,2 points, aluminum front lower control arms with cornering poise provided by Active Torque No matter which transmission option you the WRX received an IIHS Top Safety Pick+ rating pillow ball joint mounts, and a double-wishbone Vectoring. Add in available 18-inch wheels with choose—either the traditional 6-speed manual when equipped with optional EyeSight®3,4 Driver rear suspension with pillow ball bushings. Aided by inverted front struts for even less unsprung weight transmission, or the new-school Sport Assist Technology. Performance and safety don’t its sticky Dunlop® Sport Maxx RT tires, the WRX and more cornering response. -

Bbs Kraftfahrzeugtechnik Ag V Racimex Japan Kk; Jap Auto Products Kk*

CASE NOTE BBS KRAFTFAHRZEUGTECHNIK AG V RACIMEX JAPAN KK; JAP AUTO PRODUCTS KK* JAPAN OPENS THE DOOR TO PARALLEL IMPORTS OF PATENTED GOODS Case Note CONTENTS I Introduction II The Facts of the Case III The Judgment of the Supreme Court of Japan A The Applicability of the Paris Convention B The Applicability of the Patent Act 1957 (Japan) C Privity of Contract D Defining the Market, Notice and Consent E National Treatment F The Relationship between the Parties G The Segregation of Markets H Collusion between Patent Holders I Default and Bankruptcy J Unanswered Questions IV Conclusion I INTRODUCTION In BBS Kraftfahrzeugtechnik AG v Racimex Japan KK; Jap Auto Products KK1 the Supreme Court of Japan had the opportunity to decide an important question concerning the parallel importation of patent-protected goods, which it did in an interesting way.2 It held that the rights of Japanese patent holders are not infringed by the importation into Japan of patent-protected goods placed on the international market by the holder of an equivalent patent in another country. This is provided that the holder(s) of the patents in the different markets concerned are the same legal entity or licensee(s) of the same entity. The case is of significance as it directly addresses the conflict between an intellectual property owner’s desire to maximise its profits by engineering variations in price for the same goods in different markets, and the desire of entrepreneurs to * Case No H-7 (O) 1988, dated 1 July 1997. 1 Case No H-7 (O) 1988, dated 1 July 1997. -

Jazz Photo and the Doctrine of Patent Exhaustion: Implications to Trips and International Harmonization of Patent Protection Daniel Erlikman

Hastings Communications and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 25 | Number 2 Article 3 1-1-2003 Jazz Photo and the Doctrine of Patent Exhaustion: Implications to TRIPs and International Harmonization of Patent Protection Daniel Erlikman Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_comm_ent_law_journal Part of the Communications Law Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Daniel Erlikman, Jazz Photo and the Doctrine of Patent Exhaustion: Implications to TRIPs and International Harmonization of Patent Protection, 25 Hastings Comm. & Ent. L.J. 307 (2003). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_comm_ent_law_journal/vol25/iss2/3 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Communications and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jazz Photo and the Doctrine of Patent Exhaustion: Implications to TRIPs and International Harmonization of Patent Protection by * DANIEL ERLIKMAN I. Introduction.................................................................................................. 308 II. Background .................................................................................................. 311 A. International Exhaustion v. Territorial Exhaustion: The U.S. Position..... 311 B. The -

Full NX List

ISIN Description BbgSym Country Currency Exch MIC code ANN3116N1661 EUROPEAN DEVELOPMENT CAP CRP EDCC NA Netherlands EUR XAMS ANN4327C1220 HUNTER DOUGLAS NV HDG NA Netherlands EUR XAMS AT000000STR1 STRABAG SE-BR STR AV Austria EUR XWBO AT00000ATEC9 A-TEC INDUSTRIES AG ATEC AV Austria EUR XWBO AT00000BENE6 BENE AG BENE AV Austria EUR XWBO AT0000499157 CHRIST WATER TECHNOLOGY AG CWT AV Austria EUR XWBO AT0000603709 AGRANA BETEILIGUNGS AG AGR AV Austria EUR XWBO AT0000606306 RAIFFEISEN INTL BANK HOLDING RIBH AV Austria EUR XWBO AT0000609607AT0000609607 ALLGEMEINE BAU - A. PORR AG POS AV AustriaAustria EUR XWBO AT0000612601 INTERCELL AG ICLL AV Austria EUR XWBO AT0000613005 C-QUADRAT INVESTMENT AG C8I GR Germany EUR XETR AT0000617832 ATB AUSTRIA ANTRIEBSTECHNIK ATB AV Austria EUR XWBO AT0000617907 ECO BUSINESS-IMMOBILIEN AG ECO AV Austria EUR XWBO AT0000620158 AUSTRIAN AIRLINES AG AUA AV Austria EUR XWBO AT0000624705 BKS BANK AG BKUS AV Austria EUR XWBO AT0000625108 OBERBANK AG OBS AV Austria EUR XWBO AT0000625504 BANK FUER TIROL & VORARLBERG BTUV AV Austria EUR XWBO ATAT00006405520000640552BBURGENLANDURGENLAND HHOLDINGOLDING AAGG BHD AV AAustriaustria EEURUR XWBXWBOO AT0000641352 CA IMMOBILIEN ANLAGEN AG CAI AV Austria EUR XWBO AT0000642806 IMMOEAST AG IEA AV Austria EUR XWBO AT0000644505 LENZING AG LNZ AV Austria EUR XWBO AT0000645403 KTM POWER SPORTS AG KTM AV Austria EUR XWBO AT0000652011 ERSTE GROUP BANK AG EBS AV Austria EUR XWBO AT0000652250 SPARKASSEN IMMOBILIEN AG SPI AV Austria EUR XWBO AT0000676903 RHI AG RHI AV Austria EUR XWBO -

Xetra Aktien Mit

jEdit - xetra_wkn_firma.txt 1 WKN Firma 2 ====== =============================================================== 3 A0NCG9 A-power Energy Gen.sys. 4 662230 A. Moksel 5 649290 A.i.s. 6 864144 A.n.z. 7 861837 A.p.möll. 8 507990 A.s. Creation 9 938439 A.s. Roma 10 A0Q8FY A123 Systems Inc. Dl-001 11 915445 A2a 12 A0M42H Aaa Auto Grp. Nv Eo -1 13 A0MUFJ Aaa Energy Inc. Dl -001 14 A0MQ1F Aalberts Ind. Nv Eo-25 15 506660 Aap Implantate 16 540811 Aareal 17 905286 Aastrom Biosciences 18 568030 Abacho Aktiengesellschaft 19 675089 Abb Ltd. 20 919730 Abb Ltd. 21 850103 Abbott 22 862198 Abcourt Mns 23 904239 Abengoa 24 903016 Abercrombie 25 872392 Abertis Infra. Nom. 26 873886 Abiomed 27 A0M7H2 Ablynx 28 888102 Abraxas Pet. 29 A0ETUG Absa Grp 30 A0B9RG Absolute Software Corp. 31 A0L1NK Abwickl.inno.dig.med.ag 32 164631 Acacia Research Corp. 33 603035 Acadia 34 A0MWDH Acadian 35 896937 Acando 36 A0LFLF Accel Energy 37 A0CBFQ Accelrys Inc. Dl-001 38 A0YAQA Accenture 39 A0J27D Access Pharmaceut. Dl-01 40 865629 Acciona Sa 41 860206 Accor 42 A0MKWM Accuray Inc. Dl -001 43 A0DJ8E Ace Aviation 44 552863 Acer 45 889539 Acergy 46 A0JEGX Acergy 47 A0B7GP Acerinox 48 A0LCU8 Achillion 49 500740 Achterbahn 50 A0MQYA Acorn 51 A0LBDV Acorn Energy 52 A0LGJ5 Acro Inc. Dl -01 53 A0B9TS Acrongen 54 A0CBA2 Acs Act 55 936767 Actelion 56 A0LFFZ Action Energy 57 609710 Action Press 31.08.12 14:43 :: page 1 jEdit - xetra_wkn_firma.txt 58 A0HG5W Actions Semi 59 502716 Active Power Inc. -

Fachkunde Kraftfahrzeugtechnik D-ROM C Fachkunde Kraftfahrzeugtechnik

Fachkunde Kraftfahrzeugtechnik D-ROM C Fachkunde Kraftfahrzeugtechnik Europa-Nr. 20108 Druck_BC_FKFZ_20108_30_5Q_Frutiger.indd 1 13.02.17 14:14 Personenkraftwagen Geländewagen mit Hybridtechnik EUROPA-FACHBUCHREIHE für Kraftfahrzeugtechnik Fachkunde Kraftfahrzeugtechnik 30. neubearbeitete Auflage Bearbeitet von Gewerbelehrern, Ingenieuren und Meistern Lektorat: R. Gscheidle, Studiendirektor, Winnenden – Stuttgart VERLAG EUROPA-LEHRMITTEL · Nourney, Vollmer GmbH & Co. KG Düsselberger Straße 23 · 42781 Haan-Gruiten Europa-Nr.: 20108 Autoren der Fachkunde Kraftfahrzeugtechnik: Fischer, Richard Studiendirektor Polling – München Gscheidle, Rolf Studiendirektor Winnenden – Stuttgart Gscheidle, Tobias Dipl.-Gwl., Studiendirektor Stuttgart – Sindelfingen Heider, Uwe Kfz-Elektriker-Meister, Trainer Audi AG Neckarsulm – Oedheim Hohmann, Berthold Studiendirektor Eversberg van Huet, Achim Dipl.-Ingenieur, Oberstudienrat Oberhausen – Essen Keil, Wolfgang Oberstudiendirektor München Lohuis, Rainer Dipl.-Ingenieur, Oberstudienrat Hückelhoven – Köln – Deutz Mann, Jochen Dipl.-Gwl., Studiendirektor Schorndorf – Stuttgart Schlögl, Bernd Dipl.-Gwl., Studiendirektor Rastatt – Gaggenau Wimmer, Alois Oberstudienrat Stuttgart Wormer, Günter Dipl.-Ingenieur Karlsruhe Leitung des Arbeitskreises und Lektorat: Rolf Gscheidle, Studiendirektor, Winnenden – Stuttgart Bildbearbeitung: Zeichenbüro des Verlags Europa-Lehrmittel, Ostfildern Alle Angaben in diesem Buch erfolgten nach dem Stand der Technik. Alle Prüf-, Mess- oder Instand- setzungsarbeiten an einem konkreten -

Modern Automotive Technology

Modern Automotive Technology Fundamentals, service, diagnostics Bearbeitet von Richard Fischer, Rolf Gscheidle, Tobias Gscheidle, Uwe Heider, Berthold Hohmann, Achim van Huet, Wolfgang Keil, Rainer Lohuis, Jochen Mann, Bernd Schlögl, Alois Wimmer, Günter Wormer 1. Auflage 2014. Buch. 782 S. ISBN 978 3 8085 2302 5 Format (B x L): 17 x 24 cm Gewicht: 1309 g Weitere Fachgebiete > Technik > Technik Allgemein > Technik: Berufe & Ausbildung schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. EUROPA REFERENCE BOOKS for Automotive Technology Modern Automotive Technology Fundamentals, service, diagnostics 2nd English edition The German edition was written by technical instructors, engineers and technicians Editorial office (German edition): R. Gscheidle, Studiendirektor, Winnenden – Stuttgart VERLAG EUROPA-LEHRMITTEL · Nourney, Vollmer GmbH & Co. KG Düsselberger Straße 23 · 42781 Haan-Gruiten, Germany Europa-No.: 23018 Modern Automotive Technology - Fundamentals, service, diagnostics, 2nd edition, 2014 Original title: Fachkunde Kraftfahrzeugtechnik, 30th edition, 2013 Authors: Fischer, Richard Studiendirektor Polling – Munich Gscheidle, Rolf Studiendirektor Winnenden – Stuttgart Gscheidle, -

Arranjos Produtivos Locais, Políticas Públicas E Desenvolvimento Regional

Ministério da Integração Nacional Governo do Estado do Pará Arranjos Produtivos Locais, Políticas Públicas e Desenvolvimento Regional Eduardo José Monteiro da Costa Mais Gráfica Editora Brasília/2010 Arranjos Produtivos Locais, Políticas Públicas e Desenvolvimento Regional MINISTÉRIO DA INTEGRAÇÃO NACIONAL Ministro de Estado da Integração Nacional João Reis Santana Filho Secretário-Executivo Marcelo Pereira Borges Secretário de Políticas de Desenvolvimento Regional Henrique Villa da Costa Ferreira Governo do Estado do Pará Governadora Ana Júlia de Vasconcelos Carepa Vice-governador Odair Santos Corrêa IDESP – Instituto de Desenvolvimento Econômico, Social e Ambiental do Pará Presidente José Raimundo Barreto Trindade 2 Endereço para correspondência: SBN quadra 02, lote 11, Ed. Apex Brasil, portaria B, 2º subsolo, sala 201, CEP: 70041-907, Brasília, DF Esta publicação é uma realização do MI/SDR, tendo sido produzido no âmbito do Acordo de Cooperação Técnica firmado entre o Governo do Estado do Pará, e IDESP. Prefácio Prefácio o âmbito da retomada da chamada “questão regional” no Brasil, o Ministério da Integração Nacional tem pautado sua atuação nos territórios Npriorizados pela Política Nacional de Desenvolvimento Regional por meio de dois pilares básicos: organização social dos atores regionais e geração de emprego e renda, utilizando-se para tal, de sistemas e arranjos produtivos locais. Nos primeiros contatos que mantive em 2007 com o então Secretário- Adjunto de Integração Regional do Estado do Pará, Eduardo José Monteiro da Costa, soube que o autor da obra que ora tenho a satisfação de prefaciar se encontrava em processo de elaboração de tese de doutorado junto ao Departamento de Economia da Unicamp, debruçado sobre tema de grande interesse do Ministério.