Using Incidental Intellectual Property Rights to Block Parallel Imports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall Promotion

PARTICIPATING EXCHANGES: MCX Cherry Point, NC MCX MCRD San Diego, CA MCX Henderson Hall, Arlington, VA MCX Twentynine Palms, CA MCX Camp Lejeune, NC MCX Yuma, AZ MCX Miramar, CA MCX Camp Pendleton, CA MCX Quantico, VA Pre MCX advertising is part of your benefits as a member of the US military family. To opt in or out of receiving mailings or emails, please contact us by going to www.mymcx.com/mailings or Phone: (877) 803-2375. Please visit our web HOLIDAY page www.mymcx. com for additional information about MCX. We Accept These Exchange Visit our website: Gift Cards in the Store & at the Pump OUR ADVERTISING POLICY www.MyMCX.com Not all products are at all locations. Please check with your local exchange. LIKE IT? CHARGE IT! Sale This excludes limited offers and special purchase items not regularly available at your MCX. To maximize stock available to our customers, we may November 12 -17 limit quantities. We are not responsible for printer’s or typographical errors. Beat The Rush! Special catalog pricing effective November 12 - 17, 2015. No additional discounts on advertised items. Selection may vary by location. ©G&G Graphics and Promotions Inc. 0-9654A 55” 99 00 Reg. 11799 2 / 7 4GB97 KINDLE PAPERWHITE 4.33 OZ DELUXE • Higher Resolution Display, CHOCOLATE KISSES with Twice as Many Pixels 99 • Built-in Adjustable Light - Reg. 129999 Read Day & Night 1249 99 • No Screen Glare, COMPARE AT 1399 55” 4K SMART UHD TV Even in Bright Sunlight B00OQVZDJM • IPS Panel • Quad Processor / 120 Hz • Smart WebOS 2.0 / Wi-Fi • 20W Audio Output with ULTRA Surround • 3 HDMI / 3 USB and Multiple Component Inputs 55UF7600 % off Don’t Miss Our Already20 Low MCX Prices % ENTIRE SELECTION 2 Day Specials! GOURMET ENTIRE SELECTIONoff Excludes See’s Candies, 20 YOUR CHOICE WATCHES Godiva Bliss and Pages 5-8 Excludes Brighton and Caramel Gift Box 99 Pre-owned Rolex & Cartier Reg. -

This Chart Uses Web the Top 300 Brands F This Chart

This chart uses Web traffic from readers on TotalBeauty.com to rank the top 300 brands from over 1,400 on our site. As of December 2010 Rank Nov. Rank Brand SOA 1 1 Neutrogena 3.13% 2 4 Maybelline New York 2.80% 3 2 L'Oreal 2.62% 4 3 MAC 2.52% 5 6 Olay 2.10% 6 7 Revlon 1.96% 7 30 Bath & Body Works 1.80% 8 5 Clinique 1.71% 9 11 Chanel 1.47% 10 8 Nars 1.43% 11 10 CoverGirl 1.34% 12 74 John Frieda 1.31% 13 12 Lancome 1.28% 14 20 Avon 1.21% 15 19 Aveeno 1.09% 16 21 The Body Shop 1.07% 17 9 Garnier 1.04% 18 23 Conair 1.02% 19 14 Estee Lauder 0.99% 20 24 Victoria's Secret 0.97% 21 25 Burt's Bees 0.94% 22 32 Kiehl's 0.90% 23 16 Redken 0.89% 24 43 E.L.F. 0.89% 25 18 Sally Hansen 0.89% 26 27 Benefit 0.87% 27 42 Aussie 0.86% 28 31 T3 0.85% 29 38 Philosophy 0.82% 30 36 Pantene 0.78% 31 13 Bare Escentuals 0.77% 32 15 Dove 0.76% 33 33 TRESemme 0.75% 34 17 Aveda 0.73% 35 40 Urban Decay 0.71% 36 46 Clean & Clear 0.71% 37 26 Paul Mitchell 0.70% 38 41 Bobbi Brown 0.67% 39 37 Clairol 0.60% 40 34 Herbal Essences 0.60% 41 93 Suave 0.59% 42 45 Dior 0.56% 43 29 Origins 0.55% 44 28 St. -

The Business and Trade of Ahava – an Update

The Business and Trade of Ahava – An Update August 2013 The following update reveals valuable new information discovered by Who Profits: additional companies in Ahava's supply chain, natural resources from occupied territories and new EU funded research projects. In May 2012, Who Profits published a comprehensive report about the business and trade of Ahava – Dead Sea laboratories. The private Israeli cosmetic company is located in Mitzpe Shalem settlement in the occupied Jordan Valley, where it manufactures its products and exports them to more than 25 countries around the world. Natural resources from occupied territories: The Mud As Who Profits' report revealed (p. 25-30), Ahava exploits Palestinian natural resources by operating an excavation site in the occupied territory, on the shores of the Dead Sea, from which it extracts mud for its products. The Israeli civil administration confirmed that Ahava holds a license to operate a mud excavation site from the occupied area of the Dead Sea.1 Ahava has been operating this excavation site since 2004 and it is the only company licensed to do so. The mud is used by Ahava in its mud product (photo no. 1), marketed world-wide. In a research tour conducted by Who Profits in April 2013, we spotted Ahava's mud, excavated from occupied territories, stored in the company's production site in Mizpe Shalem settlement, as presented Photo no. 1: Ahava's mud products | Ahava's visitors in photo no. 2. Photo no.3 presents empty barrels for mud excavation. center, Mitzpe Shelem settlement | Who Profits | April 2013 1 Letter to Coalition of Women for Peace from the Israeli Civil Administration, 17 May 2011. -

Politicas Publicas Arranjos Pro

Universidade Estadual de Campinas Instituto de Economia Doutorado em Economia Aplicada Políticas Públicas e o Desenvolvimento de Arranjos Produtivos Locais em Regiões Periféricas Eduardo José Monteiro da Costa Orientador: Prof. Dr. Rinaldo Barcia Fonseca Tese apresentada ao Instituto de Economia da Universidade Estadual de Campinas para a obtenção do Título de Doutor em Economia Aplicada na área de concentração de Desenvolvimento Econômico. Campinas, 10 de agosto de 2007 i Ficha catalográfica elaborada pela biblioteca do Instituto de Economia/UNICAMP Costa, Eduardo Jose Monteiro da C823p Politicas publicas e o desenvolvimento de Arranjos Produtivos Locais em regiões perifericas / Eduardo Jose Monteiro da Costa. Campinas, SP: [s.n.], 2007. Orientador: Rinaldo Barcia da Fonseca. Tese (doutorado) – Universidade Estadua l de Campinas, Instituto de Economia. 1. Politicas publicas - Brasil. 2. Desenvolvimento regional - Brasil. 4. Clusters. I. Fonseca, Rinaldo Barcia da, 1949 - II. Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Instituto de Economia. III. Título. 08 -001 -BIE Título em Inglês: Public politics and the clusters development in periferic regions. Keywords : Clusters; Public politics – Brazil; Regional development – Brazil. Área de concentração : Desenvolvimento Econômico, Espaço e Meio Ambiente. Titulação : Doutorado em Economia Aplicada. Banca examinadora : Prof. Dr. Rinaldo Barcia da Fonseca. Prof. Dr. Carlos Américo Pacheco. Prof. Dr. Carlos Antonio Brandão. Prof. Dr. Cláudio Castelo Branco Puty. Prof. Dra. Edna Castro. Data da defesa: 10/08/2006. Programa de Pós-Graduação : Economia Aplicada. ii Universidade Estadual de Campinas Instituto de Economia Doutorado em Economia Aplicada Autor: Eduardo José Monteiro da Costa Título: Políticas Públicas e o Desenvolvimento de Arranjos Produtivos Locais em Regiões Periféricas Orientador: Prof. Dr. Rinaldo Barcia Fonseca Aprovada em: 10 de agosto de 2007 EXAMINADORES: Prof. -

Offers and Special Purchase Items Not Regularly Available LIKE IT? CHARGE IT! at Your MCX

PARTICIPATING EXCHANGES: MCX Camp Pendleton, CA Beauty, Bath, Body, MCX Albany, GA MCX Quantico, VA Fragrance and Skincare MCX Cherry Point, NC MCX MCRD San Diego, CA MCX Elmore, Norfolk, VA MCX Twentynine Palms, CA MCX Henderson Hall, Arlington, VA MCX Yuma, AZ MCX Iwakuni, Japan MCX Kaneohe Bay, HI MCX Camp Lejeune, NC EVENTS MCX Miramar, CA MCX Parris Island, SC MCX advertising is part of your benefits as a member of the US military family. To opt in or out of receiving mailings or emails, please contact us by going to www.mymcx.com/mailings or Phone: (877) 803-2375. Please visit our web page www.mymcx. com for additional information about MCX. We Accept These Exchange Visit our website: Gift Cards in the Store & at the Pump OUR ADVERTISING POLICY www.MyMCX.com Not all products are at all locations. Please check with your local exchange. This excludes limited offers and special purchase items not regularly available LIKE IT? CHARGE IT! at your MCX. To maximize stock available to our customers, we may limit quantities. We are not responsible for printer’s or typographical errors. Special catalog pricing effective April 6 - 17, 2016. No additional discounts on advertised items. Selection may vary by location. G & G Graphics and Promotions, Inc 0-9703 GlamO NEW Rama CALVIN KLEIN ck2 The thrill of life. A new scent for #the2ofus. ck2 – the new April 6-17 fragrance to be shared by him or her. 1.0 oz $3200 COMPARE AT $4000 NEW! $10 HOT GLAM BUYS! 1.7 oz VENDOR EVENTS • FREE GIVEAWAYS • REGISTER TO WIN BASKETS $4400 COMPARE AT $5500 3.4 oz $6000 COMPARE AT $7500 SAVE ALL 12 DAYS! Pocket Spray APRIL 6 - 17 $1600 COMPARE AT $2000 Rollerball % % $1450 $ 00 off off COMPARE AT 18 10 15 YOUR PURCHASE OF YOUR PURCHASE OF $50 AND HIGHER $100 AND HIGHER This coupon may be used more than once! Valid April 6-17, 2016. -

Monday Supplement 2019

Sponsored by: Logo in red [pms 186] MainMagazine-revised.pdf 1 13/9/19 8:41 AM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Skincare, Cosmetics & Fragrances SUPPLEMENT ® A WISH FOR HAPPINESS the tradition of giving TRAVEL EXCLUSIVE Embrace the tradition of giving with our luxury travel exclusive gift sets that create a meaningful experience for body, mind and soul. AMSTERDAM PARIS LONDON NEW YORK RITUALS.COM 03 Skin/Cos/Frag Supplement 2019 TFWA DAILY A beautiful Sustainability, clean beauty and an insatiable appetite for sheet masks… beauty suppliers reveal the hottest trends journeyand how they are building business in the channel. By Faye Bartle IDUN Minerals is seeing a trend for clean beauty. 04 Skin/Cos/Frag Supplement 2019 TFWA DAILY kincare continues to be a key growth driver of S beauty. Indeed, based on a 2018 report by Generation Research, the skincare segment contributed 47% to the growth of the perfumes and cosmetics category in 2018 compared to 2017. As suppliers pull out all the stops to keep the offer fresh and exciting, it’s easy to understand why. With plans to open a whopping 25-30 airport standalone stores over the next five years Rituals Travel Retail is not holding back. “We’re excited to announce that we’ll be opening stores at Gatwick Airport and Birmingham Airport later this year,” says Neil Ebbutt, Rituals’ Director, Travel Retail (Riviera Village RC4). “Stand-alone stores are exceptional business drivers and really give us the opportunity to deliver the ultimate Rituals brand experience with the full assortment and hallmark personalised service.” Perhaps the most significant development for Rituals in travel retail over the last six months has been the opening of a new office and distribution centre in Hong Kong to support its ambitious growth plans in Asia. -

Konzept Editorial Content AS24 Textkonzept Daniel Haefeli, 12.06.2006

Konzept Editorial Content AS24 Textkonzept Daniel Haefeli, 12.06.2006 Das Konzept Editorial Content AutoScout24 zeigt auf, wie der Editorial Content auf AutoScout24 und seiner Communities beschafft, kategorisiert, verarbeitet und publiziert werden kann. Das Konzept dient als Arbeitsanleitung für den Aufbau eines CMS und soll den mit der Umsetzung beauftragten WL-Ma- nager/GateKeeper alle relevanten Punkte im Bezug auf den Editorial Content der geplanten AS24- Community aufzeigen. Ziel des Konzepts zum Editorial Content ist, dass AS24 den qualitativ und quantitativ notwendigen redaktionellen Inhalt für den Betrieb der Plattform aufbauen und aktualisiert halten kann. Das Konzept ist in folgende Teile gegliedert: 0. Basisanalyse und strategische Ableitung 1. Redaktionskonzept 2. Marketing gegenüber Quellen 3. Contentverarbeitung und Publikation 4. Kalkulation Projekt-Start und -Betrieb Das Konzept ist primär auf die gestellten Anforderungen von AS24 zugeschnitten, besitzt aber das Potenzial, um in abgeänderter Form als Guideline für den Aufbau ähnlicher Strukturen in anderen Scout24-Bereichen die redaktionelle Betreuung zu organisieren. Die Kostenrechnung für den Editorial Content wird anhand einer Modellstruktur definiert. Die tatsäch- liche Kalkulation für die Umsetzung kann jedoch aufgrund ausstehender Verhandlungen mit Partnern, Abweichungen für Sprachübersetzungen und System der Verarbeitung/Publikation erst nach einer Konsolidierungsphase detailliert definiert werden. 0. Basisanalyse + Strategie für Editorial Content AS24 Die Grundlage für den Editorial Content AS24 wird in der Basisanalyse aufgezeigt. AS24 bewegt sich mit dem Schritt zum Aufbau von Communities weiter in Richtung eigenständiges Medium. Die Beson- derheit des Internet-Marktes ist die Kombination von Marktplatz und Werbeflächen-Verkauf. Die Funk- tion von AS24 wird von den Nutzern bezahlt (C- und B-Segmente). Dazu bietet AS24 verlegerische Dienstleistungen wie Publikation, Inserate-Verkauf und die zugehörige Administration. -

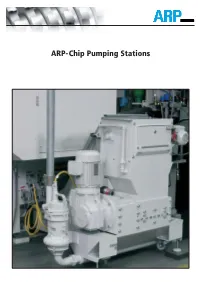

ARP-Chip Pumping Stations

ARP-Chip Pumping Stations 1 Chip Pumping Station SP 250 Drives and Performance Throughput Up to 250 litres / min Pump Screw-type centrifugal pump 1,5 kW Fitting for pump 2“ Raker Drive Spur wheel back-geared motor 0,15 kW; 57 rpm Dimensions and Weights Overall external dimensions L x W x H 1096 x 1096 x 302 mm Inner tank Ø x H 1020 x 270 mm Maximum capacity of inner tank 200 l Feed height without cutting unit At least 300 mm - Feed opening length x width Variable up to a maximum of 500 x 500 mm Feed height with ZW 400 At least 702 mm + hopper (variable) Feed height with EZ 4 recessed At least 312 mm + Trichter (variable) Feed fl ange DN 100 No. of rakers 4 Net weight Approx. 300 Kg Other Information Cutting units on carriage ZW 300, ZW 400, EZ 4 Integrable cutting units ZW 300 Level measurement „Pump On-Off“ With ultrasonic sensor Level measurement „WHG-Overfull“ With fl uid level limit switch 2 Chip Pumping Station SP 500 Drives and Performance Throughput Up to 500 litres / min Pump Screw-type centrifugal pump 4,0 kW Fitting for pump 2“ Raker Drive Spur wheel back-geared motor 0,15 kW; 57 rpm Dimensions and Weights Overall external dimensions L x W x H 1436 x 1531 x 301 mm Inner tank Ø x H 1020 x 270 mm Maximum capacity of inner tank 350 l Feed height without cutting unit At least 300 mm - Feed opening length x width Variable up to a maximum of 500 x 500 mm Feed height with ZW 400 At least 702 mm + hopper (variable) Feed height with EZ 4 recessed At least 312 mm + Trichter (variable) Feed fl ange DN 100 No. -

The German Cosmetic, Toiletry, Perfumery and Detergent Association Annual Report 2013

The German Cosmetic, Toiletry, Perfumery and Detergent Association Annual Report 2013. 2014 EDITOR IKW The German Cosmetic, Toiletry, Perfumery and Detergent Association Mainzer Landstrasse 55 60329 Frankfurt am Main Germany [email protected] www.ikw.org PHOTO CREDITS Dr. Rüdiger Mittendorff (page 2) Fotostudio Bernd Georg, Offenbach (page 6) IKW (page 7) TRANSLATION Paul André Arend LAYOUT Redhome Design, Nana Cunz EDITORIAL DEADLINE 31 March 2014 2 SITUation Dear Madam, dear Sir, 2013 was on balance a satisfying The innovativeness and orientation According to the economists, economic year for Germany and the industries towards consumer requests render growth of up to 2 % is to be expected represented by us. Despite the still these product categories particularly in Germany in 2014. A robust labour high financial and monetary policy attractive for the retail trade. market and free-spending consumers risks in the Euro space, Germany are the cornerstones of this positive recorded a slight uptrend in general Our members know how to develop forecast, which also sets the corre- economic terms, with an increase tailor-made concepts for the different sponding trends for our industries. in the price adjusted gross domes- distribution channels on the basis tic product (GDP) of 0.4 % versus of a partnership-driven dialogue, so A significant degree of uncertainty is prior year. A substantial contribution that further increases in value can be generated for our member companies was made by the domestic demand. achieved in the different categories. only by the development of energy German consumers currently have an supplies in Germany. The question optimistic view of the future as they The basis for ongoing growth is, how- concerning the extent of the burden- hadn’t had for some time. -

APPLE of SODOM AHAVA`S 5-Star/Main Launch in 2018! Apple of Sodom, a Revolutionary Product Line That Treats Wrinkles and Firms the Skin

NEW APPLE OF SODOM AHAVA`s 5-Star/Main Launch in 2018! Apple of Sodom, a revolutionary product line that treats wrinkles and firms the skin. July (New York) - AHAHA Dead Sea Laboratories, a pioneer and leader in the development and manufacturing of Dead Sea beauty products, announced this week the launch of a revolutionary product line including four new products, that will be joining its existing rich product portfolio of award-winning skin care products enriched with Dead Sea minerals. The new product line includes 24-hour cream, night mask, deep wrinkle filler and skin-smoothing essence; all products contain a revolutionary Botox- like toxin extract, a result of an extensive, 4-year research study in AHAVA`s laboratories. The Apple of Sodom is a breakthrough skin care product line, designed with revolutionary technology based on the fruit of the Apple of Sodom tree (Calotropis procera), originally found in the Dead Sea area. The Apple of Sodum is a beautiful plant; its flesh contains a milky nectar, used in ancient tribal and eastern medicine to treat various medical conditions. AHAVA is the first cosmetics company that harnesses the healing properties and toxin produced from the Apple of Sodom to create a modern anti-aging ingredient. The exclusive patented Apple of Sodom™ Complex, when combined with AHAVA’s patented Osmoter™, activates the stem cells derived from the Apple of Sodom to help skin fight against external stressors that create chronic inflammation which may accelerate skin aging. The Apple of Sodom™ Complex has been clinically proven to treat advanced wrinkles by firming and tightening facial contours. -

Download Legal Document

Case 1:18-cv-01100 Document 1 Filed 12/18/18 Page 1 of 29 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS AUSTIN DIVISION John Pluecker, Obinna Dennar, ) Zachary Abdelhadi, and George Hale, ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) Case No. _________________ ) Ken Paxton, Texas Attorney General; ) Board of Regents of the University of Houston ) System, in the name of the University of ) Houston; the Trustees of the Klein Independent ) School District, in the name of the Klein ) Independent School District; the Trustees of ) the Lewisville Independent School District, ) in the name of the Lewisville Independent ) School District; and the Board of Regents of ) the Texas A&M University System, ) in the name of Texas A&M University- ) Commerce; ) in their official capacities, ) ) Defendants. ) COMPLAINT FOR DECLARATORY AND INJUNCTIVE RELIEF PRELIMINARY STATEMENT 1. Plaintiffs challenge a state law that forces them to choose between their livelihoods and their First Amendment rights. 2. House Bill No. 89 (the “Act”) was enacted during the 2017 legislative session. It requires all who contract with the State of Texas to certify that they are not engaged in boycotts of Israel or territories controlled by Israel. Contractors who cannot meet this certification requirement or choose not to so certify are prohibited from contracting with the State. 1 Case 1:18-cv-01100 Document 1 Filed 12/18/18 Page 2 of 29 3. The Act defines “boycott Israel” broadly, so as to include taking any action that is intended to limit commercial relations with any person or entity doing business in Israel or in an Israeli-controlled territory (Tex. -

Keep Your Skin Clean and Well Moisturized

Callan-Harris Physical Therapy, P.C. Skin Care: Keep your skin clean and well moisturized. Maintain good hygiene and condition. There is a hydrolipid film of the epidermis – a mixture of water and lipids – that is created from the secretions of the sebaceous glands and the sweat that coats the skin and protects it from exogenous influences. (pH 4.5 and 5.7) (i.e. microbial colonization among other things) Reduces water evaporation and keeps the skin supple. We want to maintain this layer by using a soap free cleanser with a pH of 7 or slightly acidic (appox. pH 5). Below are some products with pH levels to compare. Sometimes in the clinic we use black tea (pH 4.9) AHAVA Soaps 5.5 MD Forte Facial Cleanser II 15%GA 3.8 Alpha Hydrox Foaming Face Wash 6.1-6.5 MD Formulations Sensitive Skin Cleanser 4.4 Alpha Hydrox Optimum Series Moisturizing Cleanser 6.3-6.5 MD Formulations Basic Facial Cleanser 5.5 Beauty Without Cruelty Vitamin C Cleanser 6.0-6.5 MD Formulations Oily/Problem Cleanser 3.8 Burt’s Bees Tomato, Carrot, and Lettuce soaps 10 Neutrogena Deep Clean Facial Cleanser 3.8-4.6 Camay Soap 9.5 Neutrogena Deep Clean Cream Cleanser 2.8-3.8 Camocare Gold Light Foaming Cleanser 6.5-7.0 Neutrogena Deep Clean Cleansing Cloths N/A Cellex-C Betaplex Cleanser 5.0-5.5 Neutrogena Extra Gentle Cleanser 5.6-6.2 Cetaphil cleanser 6.7 Neutrogena Extra Gentle Cleansing Bar 6.0-7.5 Dermalogica Exfoliants: 3.4-3.9 Neutrogena Facial Cleansing Bar Original Formula 8.7-9.2 Dermalogica The Bar 5.5 Neutrogena Fresh Foaming Cleanser 6.2-6.9 Dermalogica Dermal Clay Cleanser 6.2 Liquid Neutrogena 8.7-9.1 Dial Soap (liquid and bar) 9.5 Neutrogena Pore Refining Cleanser 3.7-4.2 Dove Bar, Baby Dove Bar 7 Neutrogena Cleansing Bar for Acne-Prone Skin 8.7-9.2 Dr.